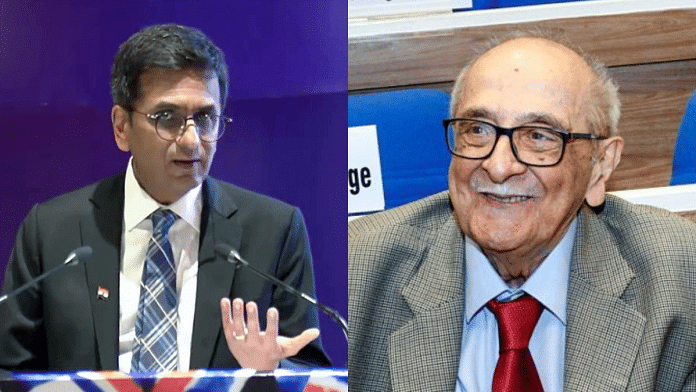

The Supreme Court Thursday convened a Full Court Reference to pay homage to senior advocate and constitutional jurist Fali Sam Nariman, who passed away on 21 February at the age of 95. Chief Justice of India Dr DY Chandrachud delivered a moving speech, saying that Nariman “embodied the fierce and unwavering commitment to the rule of law which has defined the position of the Bar after 1947”.

Here is the full text of his speech:

My esteemed colleagues, the Attorney General for India, Solicitor General and law officers and Presidents of SCBA and SCAORA distinguished members of the Bar, members of Mr Nariman’s family, Justice Rohinton Nariman, Sanaya, Nina, Khursheed Rohan, Mr Subhash Sharma who was not just a Jr. and members of the Registry.

So much has been said about Mr Fali Nariman, Accolades and tributes have been showered in rich abundance to his memory. So much remains to be said.The universe of infinity or the infinity of the universe- whichever way we perceive it – defies prose and verse. The values which Fali Nariman embodied- unflinching ethics, indomitable courage and an unwavering pursuit of principle provide a balm to the soul of the profession. In the Illiad, Homer compares people to leaves, noting that in the winter they are blown to the earth and as spring comes again, the budding wood grows once more, causing Homer to state, “And so with men: one generation grows, another dies away.” But some names remain.

Our nation has been blessed with several talented legal minds both before and after we gained Independence. But every now and then a lawyer transcends advocacy to become a leader and pillar of the community. They do so first and foremost, through their outstanding legal acumen and incredible work ethic. These foundational attributes are buttressed by subtler but equally important qualities, such as a keen understanding of a lawyer’s role in our nation’s socio-legal fabric, their integrity and courage in the face of injustice, and perhaps most of all, their compassion and willingness to help others. Through their actions, the cases they argue, their written work, and the positions they hold, entire eras of the legal profession come to be associated with their presence. Mr Nariman was unquestionably a symbol of all this and more.

While Mr Nariman’s contributions to the Indian legal profession were the result of his hard work, his very presence in India was the result of unforeseen events, or as some would say, fate. Born on 10 January 1929 in the territory that was then Burma, it was the Japanese invasion of the Indo-Pacific that caused Mr Nariman’s family to migrate to India. The arduous trek in the face of incessant bombing instilled steel in the young child who, by his own admission had until then, a rather devoted upbringing. He completed his secondary education at the Bishop Cotton School in Shimla and secured a degree in History from St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai. At the Government Law College in Bombay he was instructed by several practicing members of the Bombay Bar including Nani Palkhivala, Yeshwant V Chandrachud, and Jal Vimadalal. He was, and with the benefit of hindsight, perhaps unsurprisingly, an outstanding student who was always amongst the top of his class, securing the Kinloch Forbes Gold Medal in Roman Law and Jurisprudence and standing first in the Advocates examination conducted by the Bar Council.

The early years of Mr Nariman’s career were spent, like many of us, carefully observing and assisting senior counsel. He joined the chamber of Sir Jamshedji Kanga in Bombay. The chamber had an assembly line of brilliant juniors, – including Marzban Mistree, Rustom J Kolah, Hormasji M Seervai, Khursedji H Bhabha, Soli Sorabji, Jal Vimadalal, and Nani Palkhivala. Fali Nariman’s presence rested easy amongst his peers. He excelled, arguing case after case before distinguished judges, M C Chagla and P B Gajendragadkar (who would later be elevated to the Supreme Court and ultimately hold the position of the Chief Justice of India), S R Tendolkar and JC Shah to name a few. Mr Nariman always insisted that the more work you have, the sharper your mental faculties. Living by this principle, after a full week arguing in the Bombay High Court, Mr Nariman used to often travel to Pune to practice in the District Court, honing his skills in the art of trial advocacy. Though drawn from the Original Side, he had no air of superiority or condescension.

The phrase, “All roads lead to Rome” can aptly be modified for a great many Indian lawyers to say, “All roads lead to Delhi.” And so it was with Mr Nariman. Despite his longstanding loyalty to the Bombay Bar, he was gradually pulled in by the gravitational force of this Court, which is the ultimate arbiter of constitutional disputes, and the nation was better off for it. While still practicing in Bombay, he began appearing at the Supreme Court, most notably assisting both A K Sen and Nani Palkhivala as they argued the landmark case of Golaknath Nath v. State of Punjab before nine judges of this Court in 1967. In 1971 he was designated a Senior Advocate in the Supreme Court and in 1972 he was appointed Additional Solicitor General of India, at a time when the Union of India only had three law officers: the Attorney General of India, the Solicitor General of India, and Mr Nariman, the Additional Solicitor General of India.

As Nariman says in his book “Before Memory Fades”, “A ‘foreigner’ in Delhi has to establish himself both in integrity and ability. Only then will the Supreme Court Bar accept [them] as one of their own. But once they do, its members are the most affectionate and loyal of all comrades.” Our Bar would submit to a decree of admission that Mr. Nariman passed this test with flying colours. He represented the Union of India in this Court and at various other forums during his tenure as ASG. He argued seminal cases such as Bennet Coleman v. Union of India. He was a spirited representative of India at international events such as the conferences of LAWASIA and the International Law Association . An embodiment of the generous cultured traditions of the Parsis, he and his gracious spouse Bapsi were fall of mirth. They were joyous and spread joy in the crowd, complemented in good measure by Dhansak and a good triple. Fali possessed an unending compendium of stories about yesteryear. They were never short of his generous chuckle and the glint in the eye.

With the imposition of the Internal Emergency in June 1975, Mr Nariman resigned as Additional Solicitor General. As Martin Luther King Jr. once mused, “Cowardice asks the question, ‘Is it safe?’ Expediency asks the question, ‘Is it political?’ Vanity asks the question, ‘Is it popular?’ But Conscience asks the question, ‘Is it right?’5 Mr Nariman was guided by only one question. In his later years Mr Nariman often described how, in the days following his resignation as Additional Solicitor General, visitors to his house dried up to a trickle. However, his continued accomplishments at the Supreme Court are a testament not only to his enduring legal prowess that saw him through turbulent times, but also to that finest tradition of the Bar in rising above the disagreements of the day to unfailingly serve their clients, assist the Court, and work towards our nation’s betterment.

Despite appearing for countless clients of various backgrounds, creeds, and political dispensations, Mr Nariman always recognised that his highest duty was to the Court and the Constitution. For example, in Air India v. Nergesh Meerza, Mr Nariman was tasked with defending the national carrier’s policy of compelling air hostesses to retire upon their first pregnancy. Recognising the incongruity between Air India’s policy and the prohibition on sex discrimination found in Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution, Mr Nariman did not unthinkingly defend the policy but instead impressed on Air India the need to amend their ways. As Justice Fazal Ali recorded in the case, and I quote:

“In fact, as a very fair and conscientious counsel Mr Nariman realised the inherent weakness and the apparent absurdity of the aforesaid impugned provision and in the course of his arguments he stated that he had been able to persuade the Management [of Air India] to amend the Rules so as to delete ‘first pregnancy’ as a ground for termination of the service.”

The ultimate test of a moral person is their willingness to raise a voice for justice even when it means rocking the boat ‘(in this case, as he would say, the aircraft) , and Mr Nariman was always willing to speak for what was right and just.

Mr Nariman’s distinguished career continued throughout the remainder of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. His arguments in key cases influenced the very foundations of constitutional and public law, such as his noteworthy contributions to the Second8, Third9, and Fourth Judges10 Cases on judicial appointments in 1993, 1998 and 2014 . His clients as he would say was the independence of the judiciary. He argued cases on the rights of minority educational institutions under Article 30 of the Constitution, culminating in the seminal TMA Pai Foundation v. State of Karnataka decision.11 Away from Delhi, he was also a seasoned lawyer before the various Tribunals established under the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956, representing the State of Karnataka for over thirty years in the Cauvery water-sharing dispute.

Our time here is too brief to recount even a fraction of his noteworthy arguments in our courts, but I would be remiss to not mention the arguments he advanced in Suresh Kumar Koushal v. Naz Foundation. Mr Nariman argued that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code cannot criminalise sexual acts between consenting adults and urged the Court to change with the times. Despite the Court upholding the provision, the passage of time and the eventual overruling of Suresh Koushal in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India has since vindicated Mr Nariman’s arguments and his constitutional vision of equality and dignity. In the legal profession, the hallmark of a great lawyer is not one who wins, but one who fights well and in doing so furthers the Judges’ own understanding of the issues. Mr Nariman was amongst the very best.

Lawyers are often likened to soldiers, engaged in gladiatorial combat before the bench. But in his own tribute to Motilal Setalvad, Mr Nariman distinguished between soldiers and grand old lawyers, noting, “Old soldiers never die. They only fade away. Grand Old Men only die. But they never fade away.” Words that have a particular resonance as we are gathered here today.

Mr Nariman’s contributions to the legal profession transcended the Court. He was the President of the Bar Association of India from 1991 to 2010, and a Member of the International Commission of Jurists from 1995 to 1998. He also served as Vice-Chairman of the Internal Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce and as a Member of the London Court of International Arbitration. Public law became a part of his flesh and blood. But he was to leave a quintessential lawyer who had found his moorings in commercial law. Arbitration was close to his heart. Conferences of the PCA were never complete without his presence. In 1991 he was awarded the Padma Bhushan and in 2017 the Padma Vibhushan. In this time, he also served as a nominated Member of the Rajya Sabha (from 1999 to 2005). Despite scaling these incredible heights, Mr Nariman always maintained that greatness and modesty go hand in hand. He was a man truly in the mould of his mentor Sir Jamshedji Kanga who famously even at the age of 92 always insisted, “I am still learning!”

Even after retiring from active practice, he authored numerous articles and books that have inspired countless lawyers, the most recent of which (titled, ‘You Must Know Your Constitution’) was published a few months ago. By writing opinion pieces in newspapers on complex legal issues and constitutional doctrines, Mr Nariman tried to ensure that legal discourse is not limited to lawyers and judges, and reaches everybody. A few months ago, I had written to Mr Nariman requesting him to contribute an essay to a volume on 75 years of the Supreme Court that we will be publishing in a few months. At about noon on the day before his passing, we received an email with his essay with a gracious hand-signed note. I am also reliably informed that right until the night before his passing, he was meticulously settling the draft of a written submission for an upcoming Constitution Bench hearing on arbitration law. His mental agility, dedication to his work, and commitment to the law remained uncompromised till the day he finally rested.

Mr Nariman’s life and career before our courts lived up to the highest ideals of the legal profession. No matter the client, the government, or the case, Mr Nariman sought to advance a vision of the law grounded in liberty, equality, and justice, the foundational values of our Constitution and ultimately, our society. No matter the occasion or the opponent, he conducted himself with grace and poise.

Fali Nariman’s life straddled time and roles of personality. He embodied the fierce and unwavering commitment to the rule of law which has defined the position of the Bar after 1947. As an inveterate lawyer, Fali Nariman was that and more. He was a mentor to many on the Bar and the Bench. He had perfected the fading art of letter writing. He would share an article or eagerly enquire about areas of emerging interests like technology in which he was a self-confessed beginner. While he was not one to mince words on a judgment he disagreed with, he was equally the fond and generous senior. A day before his passing, I received a letter from him on a recent judgment. Mr Nariman fought many battles. Some of these battles continue needing to be fought. He narrated a story involving a conversation between two distinguished lawyers in our Bar library in the Emergency. One was drawing puffs on his pipe. The first said to the other:

“Tame bolo (you speak)!”

The other said

“Tame bolo! (you speak)”

When many voices fell silent during difficult times, Nariman’s resounding baritone resonated in the walls of the court and beyond. His voice represented the consciousness of the nation.

In the end, it was not Mr Nariman who gave up on these battles, it was only his body. His soul will live on in the many lives he touched and the thousands more he inspired, and his memory will always serve as a guiding light for those who pursue justice in these halls.

Also Read: Advocate Fali Nariman stood for what was right. Even at the risk of upsetting judges