New Delhi: Sanjiv Khanna’s appointment as India’s 51st Chief Justice of India will see a judge from the Delhi High Court take over the highest post in the Indian judiciary after nearly two decades. The last judge from this high court (HC) who made it to the CJI’s post was Justice Y. K. Sabharwal, who demitted office in 2006.

Outgoing CJI D. Y. Chandrachud is set to demit office on 10 November.

Justice Sanjiv Khanna’s out-of-turn elevation to the Supreme Court in January 2019 had raised many eyebrows. Ranked 33 in the all-India seniority list of HC judges, Khanna not just superseded many judges senior to him in the country, but even his three senior colleagues from his parent High Court of Delhi. With this he made it to the coveted list of six judges who have been promoted directly from their parent high court.

The top court collegium, then headed by CJI Ranjan Gogoi, was severely criticised by former and sitting Supreme Court judges for this supersession. The criticism primarily attacked CJI Gogoi’s collegium for not giving effect to a resolution nominating names for elevation to the SC but not including Justice Sanjiv Khanna—which was approved in December 2018 before one of the members retired.

In January 2019, the collegium’s constitution changed with the induction of a new judge as its member. This panel modified the earlier resolution to include Justice Khanna.

Later, in his autobiography, former CJI Gogoi defended Justice Sanjiv Khanna’s recommendation, while accepting the new collegium reviewed the December 2018 resolution. This, he said, was done to get a clear line of succession after the retirement of CJI Chandrachud as most of the judges appointed to the SC by then were due to retire before Chandrachud’s last day in office.

The controversy surrounding his appointment, however, did not linger with Justice Sanjiv Khanna, who in the last five years has dealt with a spectrum of cases as a judge of the Supreme Court. From hearing and deciding pure civil matters to cases of constitutional importance, Justice Khanna’s exposure both as a high court and then a Supreme Court judge has been very diverse.

The common themes that bind his verdicts is primacy of personal liberty, robust democratic participation and respect for individual autonomy. A source close to Justice Sanjiv Khanna told ThePrint that considering he will have a short tenure of six months as CJI, Khanna “plans to draw out a plan to bring down pendency in the top court and has already had deliberations on this”.

A Delhi HC lawyer, who has seen him work closely first as a lawyer and then a judge, vouches for Justice Khanna’s pragmatic approach and meticulous preparation. “That he chose to start his practice from the district courts, instead of rushing to either high court or Supreme Court, shows he is extremely particular about building a strong foundation.”

Also Read: Watch CutTheClutter: CJI Chandrachud’s judicial track record, from Article 370 to electoral bonds

Shouldering many legacies

A third-generation lawyer, Justice Sanjiv Khanna’s tryst with the legal profession began when he was in his teens. He was in Class 12 when his uncle Justice H. R. Khanna made headlines by resigning from the Supreme Court. Nine months before that, he stood out for authoring a dissenting verdict in the ADM Jabalpur vs Shivkant Shukla case during the Emergency in 1976.

Considered the most infamous habeas corpus case in India, the case is seen as a ‘black spot’ on the judiciary.

While his four colleagues on the bench upheld Indira Gandhi’s Emergency proclamation that curtailed Indian citizens’ fundamental rights, Justice H. R. Khanna declared the move as unconstitutional and against the rule of law. The judge paid a price. The Congress government then led by Indira Gandhi declared Justice M. H. Beg as the next CJI, while superseding Justice H. R. Khanna.

Though the commotion over his uncle’s supersession and subsequent resignation did not impact Justice Khanna directly, the “towering personality” of his uncle left an indelible mark on him as a teenager.

“His uncle’s sacrifice is part of legal history. All law students read about him, his judgment in textbooks or scholarly works related to law. He was an obvious inspiration for him (Justice Khanna), even though the two rarely interacted. The two often met at their family’s ancestral home in Dalhousie, built by Justice Khanna’s grandfather. As a young lawyer and later a judge, he always remained in awe of his uncle, hoping to emulate him in all ways,” the Delhi HC lawyer quoted earlier said.

But it was his father who influenced him to join the legal profession. Justice D. R. Khanna served as a judge of the Delhi High Court till 1985. Therefore, after graduating from St Stephen’s College in 1980, Sanjiv Khanna joined the Campus Law Centre in Delhi University and three years later, in 1983, enrolled as a lawyer with the Delhi Bar Council.

“He felt that law is his field and it was his first choice after he completed his graduation,” the lawyer mentioned earlier, said. “Maybe it is in his genes as well.”

Justice Khanna’s grandfather was well known in Amritsar during the pre-Partition era. A municipal councillor, Sarv Dayal Khanna was selected as the representative of the citizens of Amritsar for being associated with a committee constituted by the Indian National Congress in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

“People in India had more confidence in this committee than in the Hunter Commission, which had been appointed by the British government for this purpose,” noted Justice H. R. Khanna in his autobiography, Neither Roses Nor Thorns. Sarv Dayal Khanna did a good bit of recording of evidence before this committee that included C. R. Das and Moti Lal Nehru.

From Tis Hazari to Delhi HC

Despite a stellar legacy, Justice Sanjiv Khanna preferred a humble beginning in his legal career. He started his practice from Tis Hazari, even as his father was a sitting Delhi High Court judge.

“This is because he was keen to understand the fundamental principles of the profession. Working in trial courts prepares you for harder challenges in this career and prepares the foundation for future practice. This training has resulted in Justice Khanna having an elephantine memory. He is one of the rare judges who doesn’t prepare his notes on the side when he reads a case file. Yet, he cross-examines lawyers during hearings,” said one of Justice Khanna’s seniors from the Bar.

His focus on district judiciary proved beneficial for him. He got to hone his skills as an income tax lawyer, apart from practising civil law. “There were very few lawyers appearing in IT prosecution cases, which then were being filed in sizable numbers in courts. Criminal lawyers were reluctant to take up such cases as they were more documents-oriented, compared to criminal cases where there is heavy reliance on ocular evidence,” Justice Khanna’s senior further said.

Income tax counsels did not want to go to trial courts to contest these prosecutions launched by the department. Justice Khanna took advantage of this vacuum and developed his expertise in the field that reflect his judgments delivered in complicated cases of civil nature.

His practice in the HC was marked by a significant seven-year tenure as senior standing counsel for the Income Tax Department, and as standing counsel (civil) for the National Capital Territory of Delhi in 2005. Justice Khanna’s diverse legal portfolio includes contributions as an additional public prosecutor and amicus curiae in criminal matters.

His fascination for mountains, and the fact that he belongs to a family that loves hiking, takes Justice Khanna back to Dalhousie at regular intervals. He was en route to his ancestral home there in June 2005 when he got a call from then Delhi High Court Chief Justice B. C. Patel, informing about his elevation.

Justice Khanna did not flinch. He moved on with his trip, spent family time in Dalhousie and returned to Delhi four days later to take oath.

Known to be a workaholic, and someone who makes brief appearances socially, if any, in Delhi’s legal circles, Justice Khanna authored his first verdict within a week of his appointment. The judgment was on reservation for Scheduled Castes in Delhi, given that the capital does not have a status of full statehood.

‘He does not believe in rhetoric, sticks to the moot point’

Until his appointment to the top court, Justice Sanjiv Khanna delivered 4,989 judgments and 3,368 final orders. “He does not believe in rhetoric and sticks to the moot point argued in the matter. Therefore, many of his judgments are not treated as reportable as they are strictly based on facts of the case,” said a lawyer of Delhi HC who has argued several cases before the judge while he was serving there.

Some of the notable judgments of Justice Khanna in the HC include his famous opinion upholding the Centre’s 2009 notification that banned smoking on screen. He also agreed with the notification’s mandate to display a disclaimer against smoking as long as it does not disturb the continuity of the film or documentary or a serial.

In 2018, Justice Khanna headed the HC bench that quashed then President Ram Nath Kovind’s notification disqualifying 20 Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) MLAs. This notification was issued subsequent to a recommendation of the Election Commission of India (ECI) in the wake of the charge that they were holding office of profit as parliamentary secretaries.

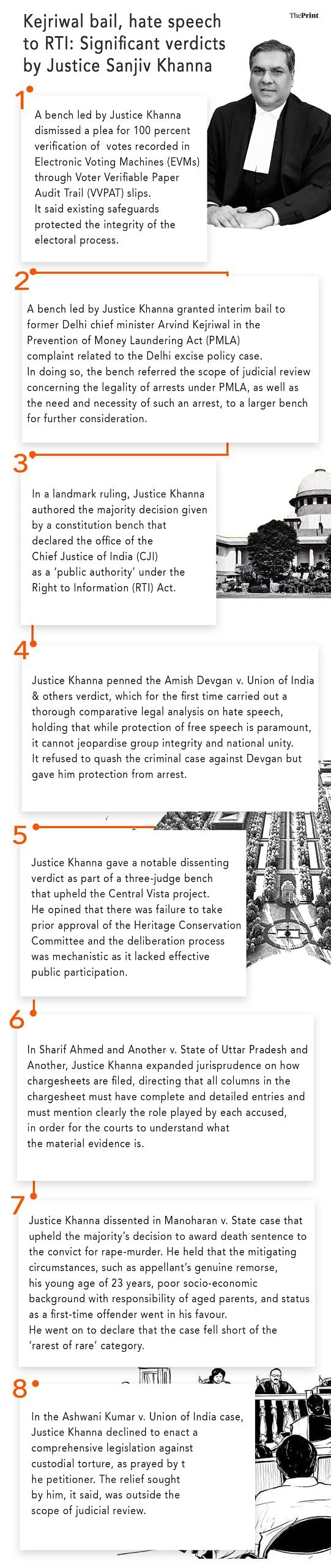

In his capacity as a Supreme Court judge, Khanna has authored several landmark rulings, and served on multiple constitution benches there. Guided by practical experience, Justice Khanna’s approach as a judge is characterised by a realistic view of dispute resolution and efficacious use of judicial time.

“Lawyers appearing before him do not have the space to venture beyond the facts of the case. He does not encourage irrelevant arguments and cuts short anyone, irrespective of whoever the counsel is, who attempts to do so,” a Supreme Court advocate said.

His practice in subordinate courts has made him large-hearted towards all lawyers, till they follow the rules of the Supreme Court, the lawyer added. “For him no party should suffer because they are unable to afford a senior lawyer of the Supreme Court and makes an extra effort to balance the equities,” said the counsel.

Due to retire on 13 May 2025, Justice Khanna has authored 149 judgments. He led the benches that delivered these verdicts. As a non-presiding judge, he delivered 159 rulings. He was one of the members of the constitution benches that upheld the abrogation of Article 370 and set aside the electoral bonds scheme respectively.

At present, Justice Khanna is also the executive chairman of the National Legal Services Authority and serves on the governing council of the National Judicial Academy, Bhopal. Under his stewardship, the National Legal Services Authority has fostered an approach that prioritises direct community engagement, strengthening access to justice at the grassroots.

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)

Also Read: DY Chandrachud ceded control to the govt. It took over judicial appointment process

Next CJI Sanjiv Khanna, just like his predecessor DY Chandrachud, is a beneficiary of the widespread nepotism in Indian judiciary.

In India, one must not aspire to be a Supreme Court or High Court judge, unless one comes from an elite legal/judicial family and has connections.