This is Part 1 of a two-part series. You can read Part 2 here.

New Delhi: An investigation by ThePrint has found that at least 30 percent of sitting judges of the Supreme Court are related to former judges, and another 30 percent have parents or grandparents who have been lawyers.

Currently, there are 33 judges in the Supreme Court, including Chief Justice of India (CJI) Sanjiv Khanna.

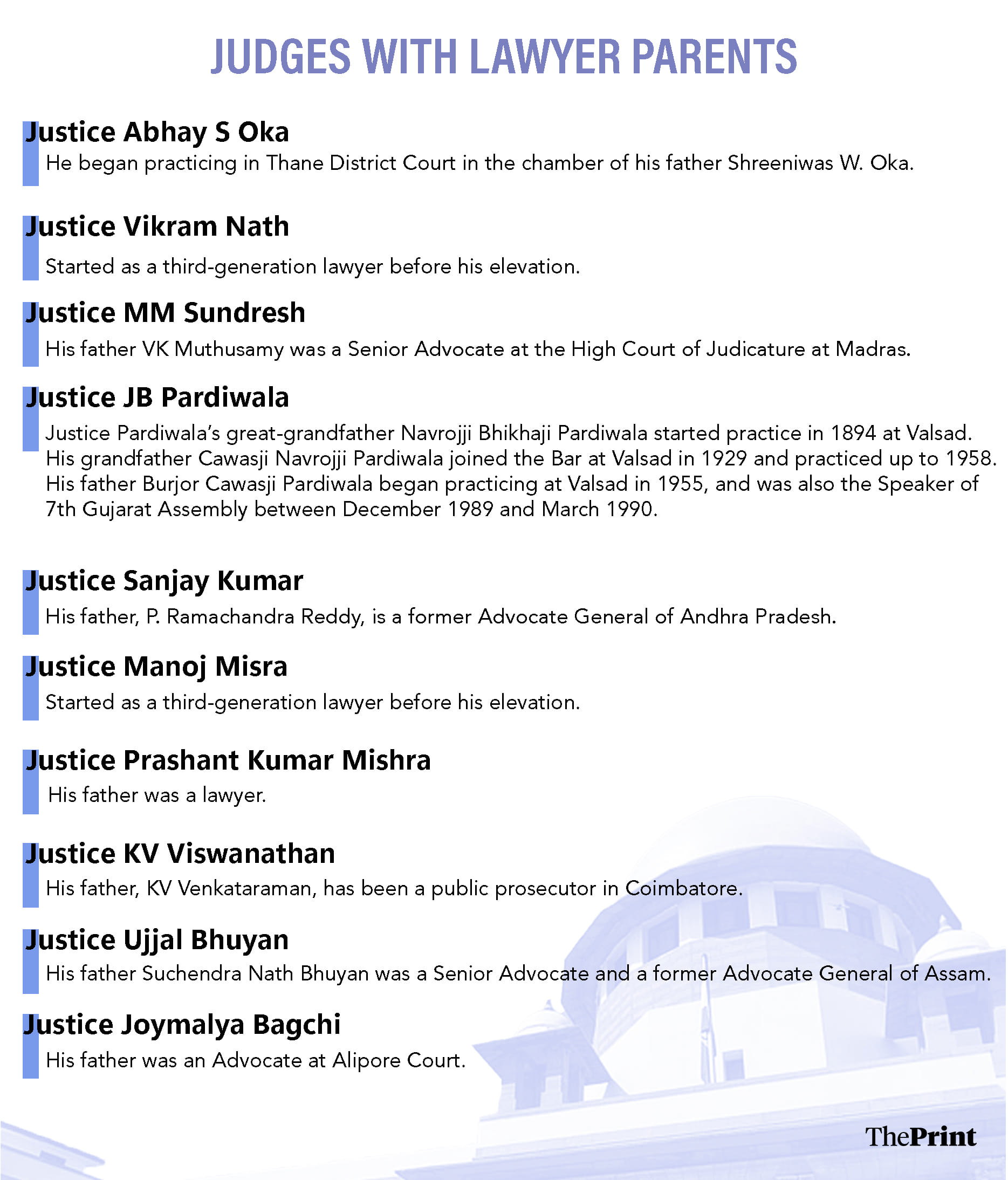

Of the 33 judges, at least 10 are closely related to former judges, while an equal number had fathers who were lawyers. This information was gleaned from publicly available resources and the respective high courts from where the judges were elevated, as well as sources from the Supreme Court.

Former Supreme Court judge Justice M. B. Lokur is not surprised by the findings. “Legacies are everywhere—medical profession, business, politics, Bollywood, civil services, and so on. The percentage may vary, but it’s there,” he tells ThePrint.

Senior advocate Indira Jaising says there are “no surprises here”. Privilege, she says, breeds privilege, what is now commonly referred to as “legacy” or “dynastic succession”. However, she asserts that adjudication is a “public service and not a business enterprise, hence, this should never have happened”.

The investigation also reveals a complex web of interconnections within the legal community—a network cutting across generations and courts.

Take the case of SC judge Manoj Misra for instance. His grandfather and father were both prominent lawyers in the Allahabad High Court, while his brother Apul Misra is a lawyer. Justice Misra’s wife Abhilasha Misra is the aunt of advocate Rajiv Lochan Shukla, who has now been recommended by the Supreme Court Collegium for elevation to the Allahabad High Court. Rajiv Lochan Shukla is the grandson of the late Justice M.N. Shukla, a former chief justice of the Allahabad High Court.

Justice Misra’s two sons Raghuvansh and Devansh Misra are practicing advocates. So is Apul Misra’s son Devvrut Misra. Raghuvansh is married to Kalpana Sinha, the daughter of former Allahabad High Court judge Justice Vipin Sinha, who himself came with a legacy.

Justice Vipin Sinha’s father was Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha, who delivered the Allahabad High Court judgment that invalidated the election of then prime minister Indira Gandhi in 1975.

Justice Vipin Sinha’s brother is married to Chhattisgarh High Court Chief Justice Ramesh Sinha’s sister. The other brother is a senior advocate in Allahabad.

The Indian judiciary therefore often has its roots firmly embedded in the legal profession, with the black robe and the gavel often being passed down generations.

However, Justice Lokur believes there are advantages as well as disadvantages to anybody born in a legal or judicial family. “A legatee has a head start because of the environment that he or she has grown up in. I think this makes a difference. On the other hand, the legatee is under pressure to succeed and not all of them do,” he told ThePrint.

According to Justice Lokur, there is a need to introduce some changes in the Collegium system, “including in the attitude of the government”.

“The government should not stop or delay the appointment of competent lawyers on an arbitrary basis. The pocket veto exercised by the government is most unfortunate. The government is a key player in the Collegium system, and it should also set its house in order before criticising the Collegium system,” he tells ThePrint.

Advocate Vrinda Grover says the findings of ThePrint “confirm that judicial appointments made by the Collegium continue to draw from a small pool of ‘legal elites’ and this perpetuates the status quo”.

Senior advocate Dushyant Dave concedes that the trend is widespread in the profession. “This is a matter of fact, and there is precious little that one can think of on how this can be stopped. It’s like a businessman’s son becoming a businessman, a doctor’s son becoming a doctor, a lawyer’s son becoming a lawyer and he goes on to be a judge,” Dave tells ThePrint.

However, he asserts that the current appointment process is “quite seriously flawed and therefore, it narrows down the zone of consideration to the relatives of current or past judges”.

“So, this needs to be broad-based so that other lawyers who are equally good, if not better, can get an opportunity for judgeship in the high courts and the Supreme Court,” he adds.

As for possible reforms, Dave does not think that the Collegium system can be improved at all, because “it is seriously inflicted with personal likes and dislikes, personal egos, and favouritism”.

“All human failings that you can think of are there in the judges who comprise the Collegium, therefore they are really not able to take the right decision,” he says. “The Collegium system has to be substituted by a more effective institution, which can protect the independence of the judiciary, while avoiding these shortcomings.”

Also Read: As SC Collegium considers proposal to tackle nepotism, how the bar views the possible move

Like parents, like children

It is well-known that CJI Khanna’s uncle was Supreme Court judge H. R. Khanna, who is known for authoring the sole dissenting verdict in the ADM Jabalpur case—arguing for the preservation of personal liberty even during a state of Emergency—in 1976.

Justice H.R. Khanna was infamously superseded by the then Indira Gandhi government, which declared Justice M. H. Beg as the next CJI instead. Justice Sanjiv Khanna’s father D.R. Khanna was also a Delhi High Court judge.

Senior advocate Saurabh Kirpal agrees that having relatives who may be judges or even senior counsel, makes entry into the system much easier with jobs than others initially.

Kirpal, the son of former CJI Justice B. N. Kirpal, asserts that the statistics may be reflective of the general privilege that comes along with being the child of a top lawyer or a top judge.

“I think this is not just a case of ‘uncle judges’ pushing for their kids or friends. I think this is a case of a systemic bias that exists within the system, which is reflected not only in the judges of higher judiciary, but possibly in every ladder of the law. And that is problematic,” he tells ThePrint.

Justice Kirpal had also served as a judge of the Delhi High Court from November 1979 before he was appointed as Chief Justice of the Gujarat High Court in 1993. He made his way to the Supreme Court in September 1995, before serving as the CJI in 2002.

Former law minister Veerappa Moily says that in 2010, he had a two-day consultation regarding the judiciary with the prime minister, SC judges, chief justices of the high courts and other former judges, along with several legal scholars.

“It emerged after discussions that the constitution of the Collegium in the states as well as at the national level needed urgent reforms…Everybody agreed that there had been infirmities and favoritism in appointments…Merited people were not being brought in,” he tells ThePrint. “There is gender favoritism, there is also caste favouritism.”

Jaising too says that the judicial system in its present form “breeds upper caste representation in the judiciary, over all other marginalised communities”.

“For some, the kith and kin of judges, this system has great advantages. We have the phenomenon of ‘uncle judge’ not by the way ‘aunty judge’,” she tells ThePrint.

Grover says that given the breadth and depth of issues that the judiciary is called upon to adjudicate, “it is imperative that the higher judiciary reflects not just regional diversity, but more importantly plurality of perspectives and experiences”.

As an example, she points out that while attention is paid to expertise in different legal fields of law for judicial appointments, in issues relating to gender, religion, caste and adivasis, “appointments are rather tokenistic than substantive”.

“The criteria for appointments are extremely narrow and do not represent the complexity of the Republic,” Grover asserts.

The exceptions

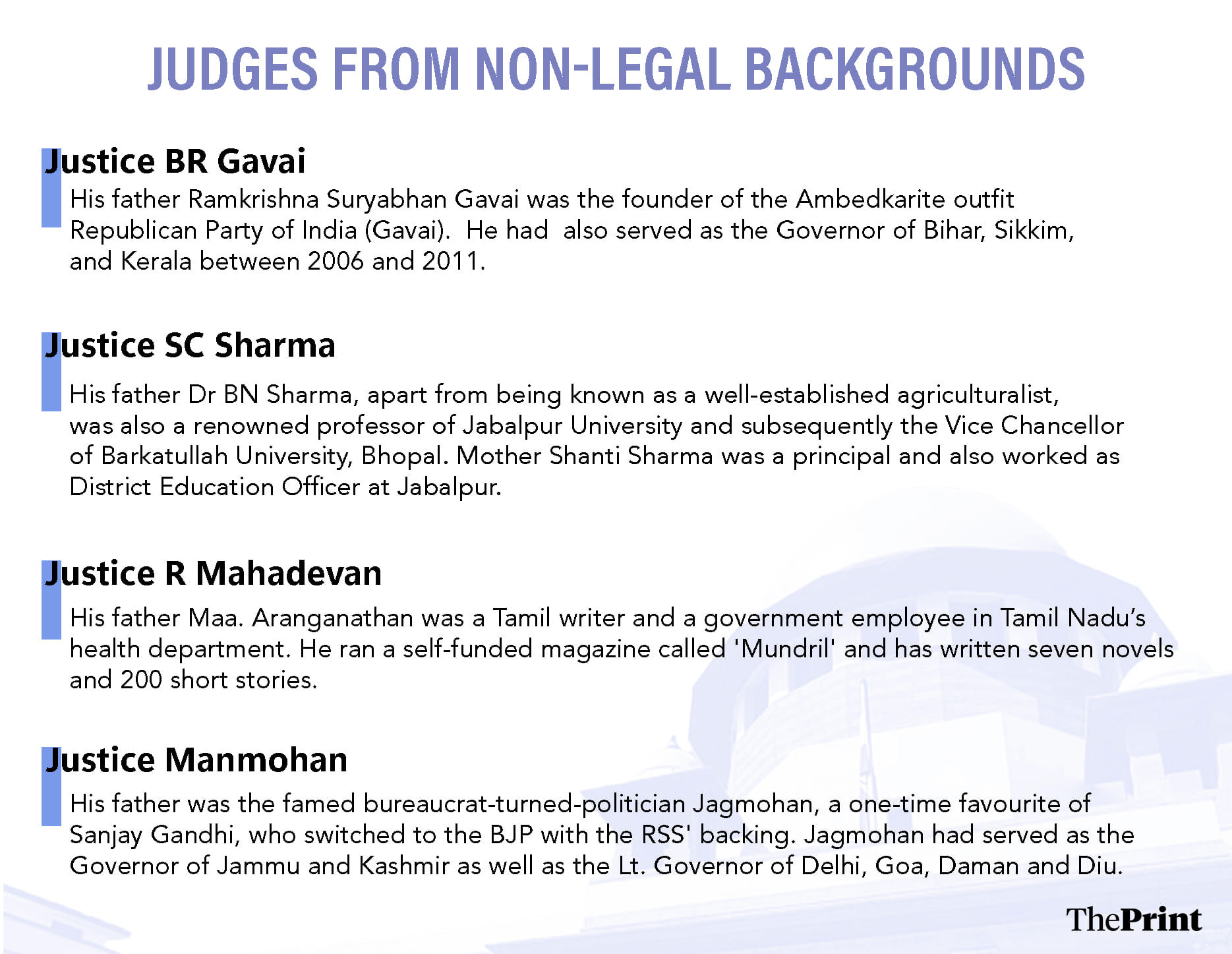

Not all judges in the top court have connections to the legal profession, however. ThePrint came across at least four sitting SC judges whose parents were civil servants, governors and even poets.

Carrying on the legacy

Recalling his own trajectory, Kirpal says that when he wanted a job, he got his father to call up a senior lawyer he wanted to work with.

“The fact that I had a double first from Oxford, that I topped my university in Cambridge, that I had in the merit list in St Stephen’s College—none of that would have made a difference to a person hiring. So my academic qualifications are not why I got that job, even though I may have had it…I just happened to be lucky,” he tells ThePrint.

He says that at the time his father was a judge, it was a clearly understood proposition that the child of a judge would not practice in the court where the parent was. This, Kirpal says, is “sadly now something that isn’t necessarily happening as much as it should now”.

“So when my father was in the Supreme Court, I could not even enter the Supreme Court.”

In fact, Kirpal says that when his father became a judge in the Supreme Court, he left practicing law for three years. “From 2000 to 2003, when he was the top judge, I was working with the UN in Geneva. So, I left the country to make sure that there would be probity, and no one could point any fingers.”

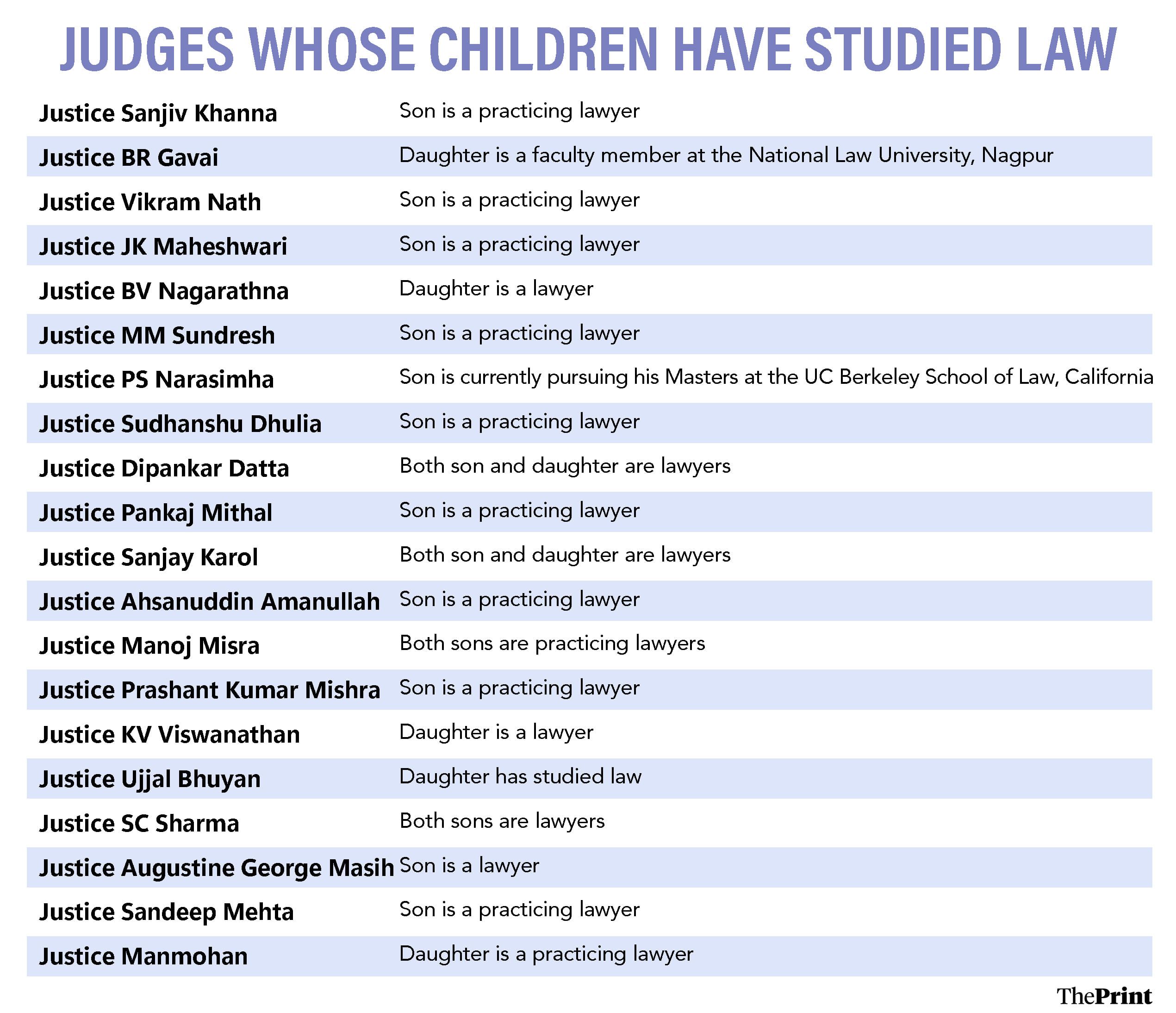

However, this seemingly isn’t the case anymore. Currently, at least 60 percent of the sitting Supreme Court judges have children who have studied law, with some of them practicing in Delhi and in various other courts across the country, according to sources in the apex court and various high courts where these children are practicing.

Their lineage has made headlines in the recent past like in the case of Padmesh Mishra. Last year, Padmesh, the son of Supreme Court judge Prashant Kumar Mishra, was made the Additional Advocate General (AAG) for Rajasthan. His appointment coincided with an amendment in the state’s Litigation Policy which allowed for the state government to appoint someone to the post without adhering to the requisite 10-year experience norm.

Mishra’s appointment as well as the clause added to the Litigation Policy were challenged. While a single-judge bench of the Rajasthan High Court rejected the challenge, an appeal challenging the order has now been filed before a two-judge bench of the high court.

Jaising says that no judge has attempted to address this problem, where sons and daughters of judges appear in the same court in which their fathers are judges “on the spurious logic that they keep away from their fathers”.

Acknowledging the privilege that comes along with belonging to the family of a judge or a lawyer, Kirpal points to the perceptions that may follow a judge’s son or daughter in court, which may be a “disadvantage” for them.

Kirpal knows a thing or two about the “disadvantages”. In 2017, his name was first proposed for elevation as a Delhi High Court judge in 2017, by the HC Collegium. His candidature has since been a point of contention between the Supreme Court Collegium and the government—the latter objecting to his partner being a Swiss national and “his intimate relationship” and openness about “his sexual orientation”.

The perception within legal circles, he says, has been that his name was recommended just because Justice D. Y. Chandrachud’s father Y. V. Chandrachud appointed his father as a judge. “None of it is true, of course, because there was no Collegium system when my father was appointed, but that doesn’t matter to people. They would automatically belittle and demean any achievement of a person, because they’ll say that you are the child of a judge,” Kirpal tells ThePrint.

Before the Collegium system was brought in through Supreme Court judgments in the 1990s, the executive had the primary say in judicial appointments in the years leading up to the establishment of the Collegium system. This involved appointments being made by the President, acting on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers, in “consultation” with the Chief Justice of India.

Also Read: 8 of 25 high courts have only 1 woman judge. Data shows poor representation in higher judiciary

‘Inward looking’

Even as there is a general consensus over the existing infirmities in judicial appointments, there are divergent opinions among the legal fraternity over bringing in more diversity within the judiciary.

Senior advocate Vikas Singh says that his grievance with the Collegium system has been that they have been “looking inwards”.

“I’m not saying that their children don’t deserve to be elevated, but in the process of elevation, you’re only looking at people you know or who you’ve heard about…This is why the Collegium system is losing credibility,” the Supreme Court Bar Association’s former president tells ThePrint. “Because of this inward look, automatically biases and favoritism come in.”

Singh stresses on reinventing the existing system of appointment, with specific criteria being spelled out for who can become a judge.

Jaising believes that reform or restructuring of the Collegium is a must. “Applications for appointment at a judge must be invited, and the consideration of the person must be held in public,” she told ThePrint.

As for Grover, while she does support the Collegium system over an alternative like the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), she adds a caveat: “If the Collegium system is to remain relevant and hold public trust it must reconfigure the criteria and considerations involved in judicial appointments. It’s high time judicial appointments were aligned to constitutional principles and goals, which necessarily involves dismantling privilege and democratising the composition of the higher judiciary.”

However, Kirpal views the statistics as a problem of exclusion at the entry levels in the legal profession. “When a senior pays only Rs 20,000 or Rs 15,000 to an entry level person, that is the problem also. The basic problem which we have is the elitism in the legal profession and that cannot go away by this process of understanding what is happening at the very top,” he explains.

Providing better access and opportunities to deserving litigating lawyers are his suggestions. “It is very much an old boys’ network about how you get a placement in a top senior’s or in a good senior’s chamber.”

While most critics of the Collegium system are quick to suggest an alternative on the lines of a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), Kirpal doesn’t think that would guarantee a more inclusive judiciary.

“This is a problem of India. Every time a politician gets power, it becomes a hereditary phenomenon. The same thing will happen with judges. We need constant solutions, and the only answer is getting an exceptional group of lawyers,” he asserts.

Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: 19 FIRs, 15 yrs, zero accountability—unresolved saga of CWG ‘scam’ that changed Delhi & its politics