New Delhi: In the early hours of a foggy January morning in 2018, former Army officer Naresh Dhankar allegedly went on a “killing spree”, taking six lives with an iron rod. He was dubbed the “psycho killer” of Palwal even before the trial, but he was also given an official diagnosis of bipolar psychosis.

A Haryana additional sessions court sentenced Dhankar to death in March 2023, rejecting his plea of innocence and ruling that psychiatric disorders could not be equated with insanity. The court dismissed the pleas of the defence counsel, who argued for reformation through proper treatment.

Dhankar is among the 56 convicts who have been sentenced to death in the last 14 months in 26 trial court judgments that failed to consider the latest Supreme Court guidelines on materials that need to be evaluated while awarding capital punishment, research by ThePrint has revealed.

On 20 May 2022, a landmark Supreme Court ruling — Manoj vs The State of Madhya Pradesh— emphasised the importance of considering rehabilitation in capital punishment cases and also laid down guidelines for the collection of mitigating material by trial courts

The judgment said that courts must consider a convict’s conduct in jail, as well as psychological and psychiatric evaluation reports, in order to assess the possibility of reform. The convict’s social background, age, educational level, any trauma they may have experienced in their life, and family circumstances should also be taken into account, it added.

However, a scrutiny of death penalty judgments handed down by trial courts in the past 14 months paints a different picture.

In 89 percent of these cases, the judgments did not reference the Manoj judgment as precedent. Additionally, in 92 percent of cases, trial courts did not request psychological and psychiatric evaluation reports for the convicts.

In the two cases in which such reports were sought, the trial courts failed to clarify their role in the sentencing decision.

Instead, several courts across the country are still emphasising disproportionately on the brutality of the crime to justify the death penalty. Some judgments even cited the absence of remorse on the convict’s face or the use of capital punishment as a deterrent to hand down death sentences.

Speaking to ThePrint, Anup Surendranath, a professor of law at Delhi’s National Law University (NLU) and executive director of Project 39A, NLU’s criminal justice programme, said that there is an “ever-widening gap” between the Supreme Court’s guidelines for sentencing in capital cases and trial courts’ death sentence orders.

“They almost seem to be operating in parallel universes with the trial courts not even acknowledging the changes that the Supreme Court has brought about in death penalty sentencing in the last year or so,” he said.

No mental health report sought in 24 out of 26 cases

In the Manoj judgment, the Supreme Court put the onus on the state to present the psychiatric and psychological evaluations of the accused before trial courts in capital punishment cases.

“This will help establish proximity (in terms of timeline), to the accused person’s frame of mind (or mental illness, if any) at the time of committing the crime and offer guidance on mitigating factors,” the verdict said.

The court cited the 1980 Bachan Singh judgment, which had upheld the constitutional validity of the death sentence, but on the condition that it could be imposed only in the “rarest of rare” cases. The Bachan Singh judgment had also urged courts to consider mitigating circumstances such as the accused being mentally or emotionally disturbed or acting under the duress or domination of someone else.

Further, it had emphasised evaluating whether the “condition of the accused showed that he was mentally defective and that the said defect impaired his capacity to appreciate the criminality of his conduct”.

The Manoj judgment added that such an evaluation would also help the court ascertain the accused’s progress in prison and their potential for rehabilitation.

Surendranath explained that following the Manoj judgment, there are three key sets of materials that a sentencing court must consider.

The first is evidence provided by the prosecution to support their case for the death penalty.

Second, the court should request two essential reports on the accused’s mental state — one from the prison detailing his or her life and behaviour while incarcerated, and another from an independent mental health professional about the accused’s psychological condition.

Finally, there should be “mitigation investigation reports” submitted by the defence, based on information gathered by a mitigation investigator.

However, an evaluation of 26 sentencing orders by ThePrint revealed that in 24 cases, the trial court did not seek a mental health professional’s report. None of the 56 death sentences showed submission of mitigation investigation reports submitted by a mitigation investigator.

Surendranath stressed that this aspect of the Manoj judgment is to ensure that “there is some semblance of fairness in the sentencing process when the prosecution seeks a death sentence”.

Two exceptions, but limited adherence

Out of the 26 cases, there were two that stood out. Both these judgments were passed by the sessions court in Sonipat, albeit by different judges. One was an ‘honour killing’ case in which two people were sentenced to death on 29 May 2023, and the other was a rape and murder in which two men were awarded capital punishment on 19 December 2022.

Each cited the Manoj judgment and sought reports regarding the respective convicts’ behaviour from the Superintendent of District Jail, Sonipat, and the District Probation Officer, Sonipat. Additionally, they requested mental health assessments from the psychiatric department of Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences (PGIMS), Rohtak.

However, that was the extent of their adherence to the Supreme Court’s guidelines. The two judgments did not mention how the court is taking the reports into account or their role in decision-making.

In the first judgment, passed by additional district and sessions judge (fast track court) Salender Singh, the court noted that “as per report of medical board, both convicts are mentally fit and they are not suffering from any psychiatric illness and no psychiatric medicine are indicated”. However, the reports don’t feature in the discussion on evaluation of mitigating and aggravating circumstances after this.

Curiously, two full paragraphs in the two sentencing orders, detailing the arguments on behalf of the accused, are exactly the same, word to word. This is despite the fact that the orders were pronounced by two different judges, and the accused were represented by different advocates.

Did trial courts fulfill their duty?

In the Manoj judgment, the Supreme Court ruled that trial courts must proactively seek out mitigating circumstances in death penalty cases. It also provided guidelines for collecting such information.

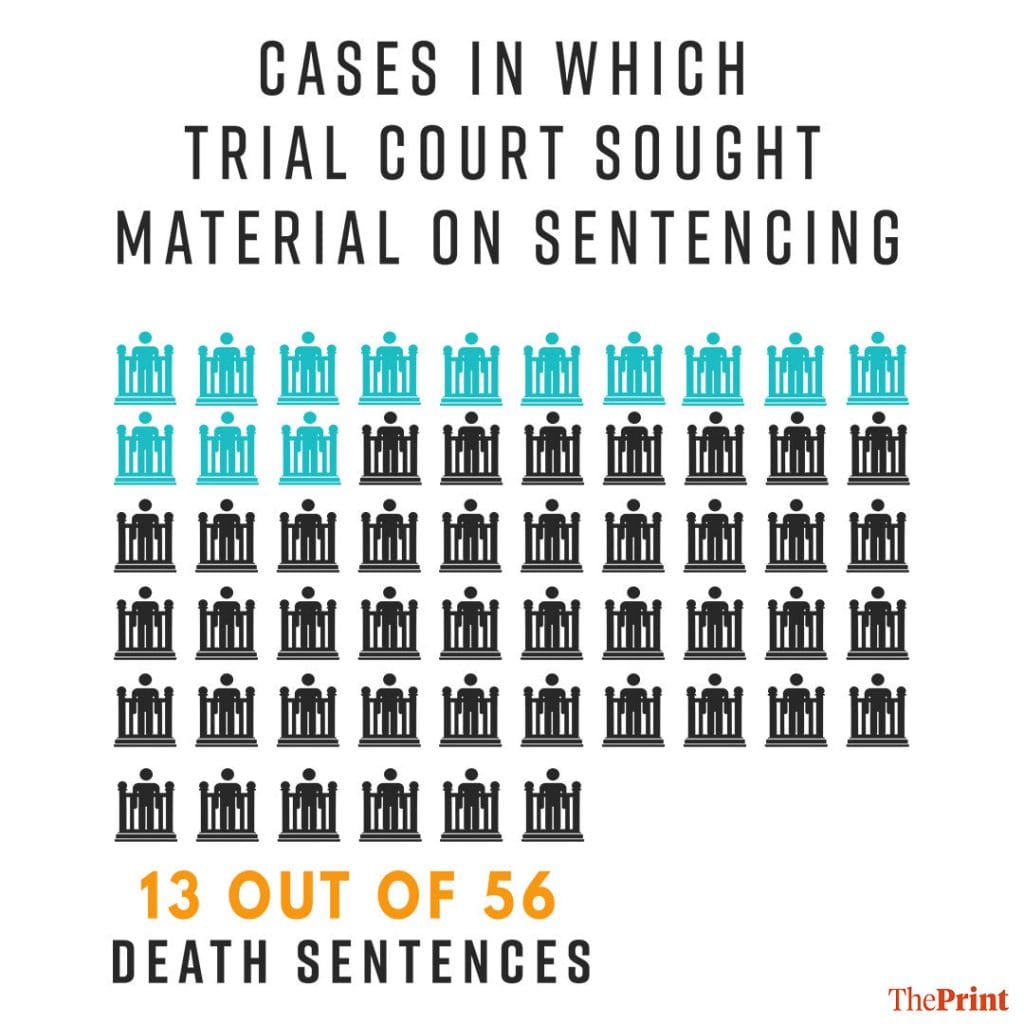

However, ThePrint’s analysis of the 56 death sentences revealed that trial courts only pursued specific sentencing material in four cases, which accounted for 13 death sentences in all.

Sentencing material refers to the offender’s history, crime circumstances, and mitigating or aggravating factors. It is presented during a sentencing hearing after conviction and helps the judge in determining an appropriate sentence.

One of these cases involved the rape and murder of a 5-year-old girl in Jhargram, West Bengal, for which a special court sentenced two men to death in June this year.

In this case, the court requested a report from the Superintendent of Special Correctional Home, Jhargram, seeking information on the “illnesses or unstable behaviour of both the convicts” inside the jail or correctional home. It also asked if any work was done by them, and about their involvement with matters inside the jail or correctional home.

Similarly, in the two cases from Sonipat cited earlier, the respective judges asked for reports from the jail superintendent and the probation officer, other than mental health evaluations. However, as mentioned previously, the judgments did not explain whether or how these reports were taken into consideration while deciding in favour of awarding the death penalty.

The fourth judgment involved a terror conspiracy case that led to seven death sentences. However, in this case, the court only requested the prosecution to provide information on the accused’s past criminal record. In this case, the criminal background of the accused formed the basis of the court’s reasoning for imposing the death penalty.

Notably, in September last year, a Lucknow court sentenced two men to death for the double murder of a father and son. However, instead of soliciting materials on the accused, the court focused on the psychological state of the wife of the victim.

The court claimed that when the authorities tried to contact the wife on the address available on record, they found out that she sold the property and moved soon after the incident.

The court then observed: “It is natural that in a family whose father and only son are murdered in a brutal manner in broad daylight, the state of fear of the remaining female members in that family would be unimaginable. That is why she must have started living at some other place other than the given address where the fear of the accused could not haunt her.”

Questions of reform, ‘insanity’

The Manoj verdict had noted that the Bachan Singh judgment had tasked courts with assessing several key aspects, including: the likelihood that the accused “would not commit criminal acts of violence as would constitute a continuing threat to society,” and the potential for the accused’s reformation and rehabilitation.

Importantly, the 1980 verdict had stipulated that the prosecution must provide evidence demonstrating that the accused does not meet both these conditions.

In other words, the Manoj judgment reiterated the prosecution’s duty to present evidence to show the unlikelihood of reform whenever seeking capital punishment.

However, out of the 26 cases, the prosecution only presented such evidence in four instances. And in three of these cases, the evidence pertained only to the prior criminal history of the accused.

Conversely, the defence lawyers in these cases did try to highlight possible mitigating factors for the accused. For instance, defence counsel cited the young age of at least 12 convicts and the lower socioeconomic background of 14 as mitigating factors. In addition, 12 convicts argued that they have dependents, and 18 cited not having a criminal history to plead against the imposition of the death penalty.

However, the court often rejected the mitigating circumstances as irrelevant, or even failed to consider them in several instances.

Then, for at leastfour convicts, the defence also raised the issue of mental illness.

One such case was that of Palwal’s Naresh Dhankar. His lawyer had pointed out that Dhankar was discharged from the Army due to his “psychiatric problem” and had also submitted that the former officer was suffering from “bipolar psychosis” since 2001, the judgment shows.

The Assistant Superintendent of District Jail, Faridabad, also told the court that Dhankar was “disoriented to time, place, and person” and a jail report confirmed his bipolar disorder and that he was receiving psychiatric treatment while in prison.

The Palwal court, however, rejected this submission in the conviction as well as sentencing orders, refusing to treat bipolar psychosis as “insanity”, among other things. The sentencing order claimed that “77 lacs Indians suffer from bi-polar psychosis, and the same is a common disorder like anxiety and insomnia” (sic).

The court asserted that “it is not insanity, by any stretch of imagination”.

‘No guilt on his face’

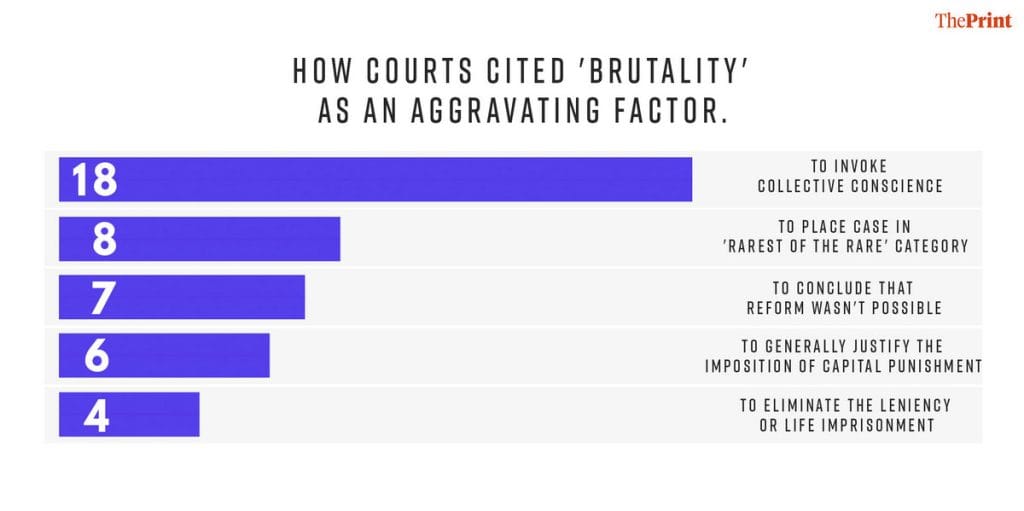

At least 44 of the 56 death sentences — forming 78 percent of the dataset— cited the brutality of the crime as an aggravating circumstance for imposing the death sentence.

These judgments described the crime in extensive detail, with some dwelling at length on the deceased victim’s injuries.

The Bachan Singh judgment had asserted that in order to qualify as an aggravating circumstance, brutality must be to “an abnormal or special degree”. However, the courts often failed to provide substantial reasons for why the manner in which the crime was committed was abnormally or especially brutal.

Among the 44 sentences that referenced brutality, eight used it to classify the case as “rarest of the rare,” 18 to invoke the “collective conscience”, seven to argue against the convict’s reformation prospects, and four to eliminate the possibility of leniency or life imprisonment. Furthermore, six sentences utilised brutality as a general justification for imposing the death penalty.

Speaking to ThePrint, Surendranath criticised the “crime-centric” approach adopted by the trial courts.

“The layperson on the street might want that crime-centric approach to determining punishment, but that’s not what the law requires. Ultimately, our judges must realise that their duty is to give effect to the law and not to the collective conscience or public opinion,” he said.

“We call it the ‘rule of law’ and not the ‘rule of persons’ for a very good reason,” he added.

In at least six death sentences, the courts also established the remorselessness of the accused without actually referring to any statements or even demeanour of the accused. In fact, most frequently, no reasons were provided at all.

For instance, in a case concerning the rape and murder of a 9-year-old boy, a court in Mathura foreclosed the possibility of reformation of the convict by saying that “during the trial, he kept coming to the court every day, but no feeling of guilt appeared on his face”. Recalling the matter in which the crime was committed, it then observed, “Keeping in view the criminal mindset of the convict, it can be said that there is no possibility of reform in his future”.

While sentencing 14 convicts to death row, the court cited deterrence as a goal. The court reasoned that the death penalty was necessary to warn other potential offenders, to set an example, and to discourage other people from committing similar acts.

Death in less than 2 days

In September 2022, the Supreme Court acknowledged the gaps in death penalty sentencing, and asked a five-judge bench to look into framing guidelines on potential mitigating factors to be considered while imposing capital punishment.

One of the issues that this larger bench is set to examine is the amount of time that a convict must be given to present relevant material after the conviction but before the sentencing hearing takes place.

In its September 2022 order, the apex court acknowledged that there was no clarity on the issue. It asserted that courts have acknowledged that “meaningful, real and effective hearing must be afforded to the accused with the opportunity to adduce material relevant for the question of sentencing”. However, what was lacking was the amount of time that this may require.

In the 26 judgments examined by ThePrint, the sentencing hearing took place within two days or less after conviction in 10 instances. In another nine instances, the death penalty was awarded within three to seven days of convicting the accused.

Surendranath explained that putting together the life history of an accused before the crime and the time spent in prison requires time and skills that go beyond that of a lawyer.

“Given the nature of the inquiry that the defence team has to undertake by having complex conversations, not just with the offender but their family, friends, and acquaintances, it is not difficult to see why sufficient time between the date of conviction and sentencing hearing is essential,” he explained.

However, at the same time, he laid emphasis on the quality of the information gathered in this time, “to ensure that judges are able to truly understand the person they are looking to sentence”.

“Therefore, the Supreme Court is right in its position that a meaningful hearing has to be judged in terms of quality. But sufficient time has to feed into the quality question and evaluation of what constitutes a meaningful sentencing hearing,” he added.

The other Manoj

While a majority of the judgments examined by ThePrint don’t acknowledge the Supreme Court’s guidelines in the landmark Manoj judgment, another judgment bearing a similar name features in at least three orders.

In June 2022, the Supreme Court in Manoj Pratap Singh v State of Rajasthan upheld the death penalty awarded to a man for kidnapping, raping, and killing a seven-and-half-year-old mentally and physically challenged girl in 2013.

In doing so, a three-judge bench headed by Justice AM Khanwilkar observed that the quest for justice in death penalty cases “does not mean that the matter would be approached and examined in the manner that death sentence has be avoided”.

It noted that while collecting mitigating material, the idea shouldn’t be to somehow find something that could help in avoiding the death penalty.

The court observed: “The pursuit in collecting mitigating circumstances could also not be taken up with any notion or idea that somehow, some factor be found; or if not found, be deduced anyhow so that the sentence of death be forsaken. Such an approach would be unrealistic, unwarranted, and rather not upholding the rule of law.”

The sentencing order passed in the Jhargram case favourably cited the Manoj Pratap Singh judgment.

In another case pertaining to the rape and murder of a six-year-old girl in Gujarat’s Dahod, the accused person’s lawyer cited the first Manoj judgment. However, the Dahod court relied on the Manoj Pratap Singh judgment instead.

Similarly, in a case pertaining to the murder of an inmate in Jamshedpur Central Jail, the prosecution relied on the apex court’s observations in the Manoj Pratap Singh judgment.

‘Incorrect application of law’

Surendranath told ThePrint that in death penalty cases, many trial courts apply the law in a “blatantly erroneous fashion, riddled with erroneous procedure, incorrect application of law and arbitrariness”.

He added that the Supreme Court is “acutely aware of the crisis that afflicts death penalty sentencing in India” and is attempting to remedy it— but whether it can actually fix the problem is a different question altogether.

When asked the reasons behind these “erroneous” practices, Surendranath said there could be several explanations, none of which cast the district courts in a good light.

“Either they are unaware of what the law on death penalty sentencing requires or, despite being aware, they ignore it because it has stringent and demanding requirements,” he explained.

Surendranath also argued that simply changing the law or making guidelines is not enough. He said that it is also important to ensure that trial judges understand the changes and have the resources to implement them.

“How should judicial academies design their training to ensure that judges are aware of the requirements of the law? Considering that the law is embedded in society, do judicial academies do enough to sensitise judges to keep away their biases from decision-making? Are trial courts well equipped with resources to meet the demands of the formal law?” he asked.

With inputs from Aditya Roy, an intern at ThePrint

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Are courts awarding too many death sentences? 539 convicts on death row in 2022, highest in 17 yrs