As the nation battled the coronavirus pandemic, Bhilwara — a small town in Rajasthan that is 240 kilometres from Jaipur — reported increasing number of Covid-19 positive cases.

After the detection of Covid-19 among six staff members of the Brijesh Banger Memorial Hospital on 19 March, the news updates said there was a risk of community spread in the town as it was a popular hospital among patients.

By the time the news was reported in the national media, there were 21 positive cases of coronavirus in the town and we decided to go and find out how the administration was trying to contain the situation.

To be honest, we were quite nervous about this assignment because coronavirus is extremely easy to transmit and since it stays on surfaces for hours, we were worried that we may bring not just stories from Bhilwara, but also the virus.

The national lockdown, ban on travel and closing of all hotels made planning this trip extremely difficult, but someone managed a vehicle and we started on the nine hour journey.

While both of us had read up on the tips needed to protect against coronavirus, we were very anxious.

Between the two of us, we had sanitiser, soaps, food and water as well as N-95 masks and gloves.

Buses parked on road while families walked on foot

With a nation under lockdown, it was strange to be on the highway without a single car. Within a few kilometres, however, we saw young men with backpacks walking on the side of the highway.

The first few told us they had to walk hundreds of kilometres to reach their homes as there was no transportation available. It felt so unfair to see trucks and buses parked on the road while families walked on foot. We felt guilty zooming past them in the luxury of our car.

It soon started raining and we wondered what would become of them.

When we left for Bhilwara, we knew the district was under a lockdown and its borders sealed. Since we were to reach late at night, we weren’t sure what the border police would do, so we decided to make a stopover at Ajmer which is 115 km away.

Thankfully, one hotel accepted our online booking and we had a roof over our heads.

The next day we had to leave for Bhilwara. There was some uncertainty about whether we would be allowed to enter as the city was under complete lockdown.

Bhilwara went under lockdown even before a nation-wide lockdown was announced by the Narendra Modi government.

We saw that the entry to the town was barricaded, and policemen wearing gloves, masks were guarding it.

Anyone who had to go in or out of the town had to have a written pass from the district magistrate.

A group of government employees asked us to register our vehicle too. We were relieved at being let into the town.

Incidentally, the hoarding beside the entry point was of the Brijesh Banger Memorial Hospital, where the first doctor was affected and started the chain of transmission in the town.

‘This is our work, why would we be afraid’

In Bhilwara, besides the administration, the health workers had an important task — to visit each household, note down the details of their illness and talk to them about preventing the coronavirus spread.

The health workers told us about their routine, how at the end of their day they go home and soak their clothes in soap and Dettol water and wash their hair and body. We asked them if they were scared but they smiled and said, “nahi madam, yeh toh humara kaam hai, kyun dare (This is our work, why would we be afraid?)”.

They advised us to maintain six feet distance while interviewing people and to cover our hair.

While Swagata removed her mask to do a piece to camera and drink water, Manisha decided to keep hers on till she left the city.

We were careful to not touch any surfaces and kept pouring sanitiser over our gloves.

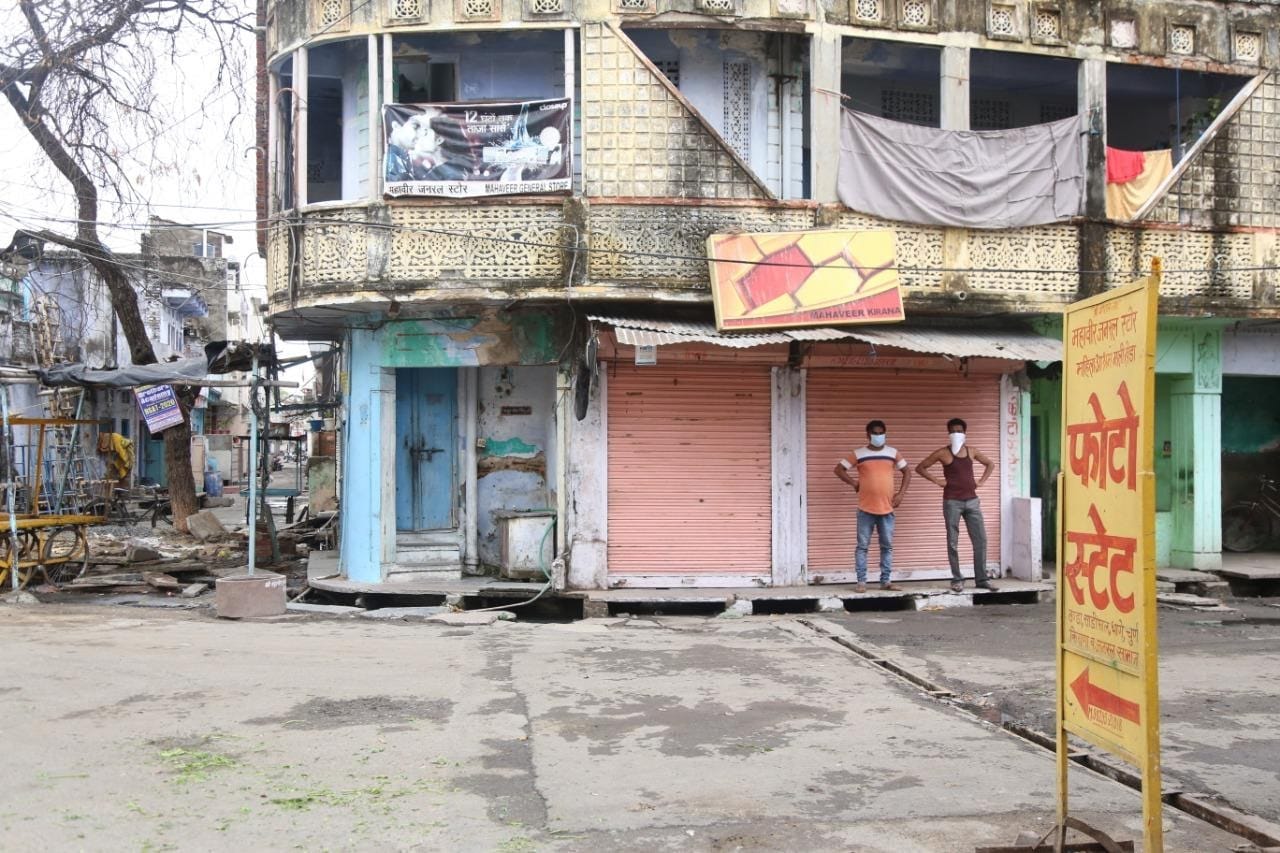

The city was under lockdown but there was still some movement of people, much more than we have seen in Delhi. However, the lanes manned by the police were deserted.

Strange as it may seem, while we were covered in masks, gloves, afraid to touch anything or go closer to people, some residents stood outside their homes without protection. A few minutes later, we also saw women in traditional attired celebrating a festival called ‘Gaurpuja’.

We had to meet the District Magistrate to assess the entire situation. But he was busy, as were most officers we wanted to meet.

At the Collectorate, we spotted a man wearing a dhoti spraying sodium hypochlorite, a bleaching liquid that kills the virus.

When Manisha went after him, she saw an official call him to the same room we were in a few minutes back. “Aapko bola hai na iss room mein bahut log aate hai, thori thori der baad sanitise kia kariye (a lot of people come to this room, sanitise it frequently),” said the official.

‘Why are you wearing masks and gloves?’

Our next stop was the Mahatma Gandhi hospital where the Covid-19 positive patients were isolated and treated.

The moment we entered the office, a senior health official said, “Why are you two wearing masks and gloves?” He asked us why we came to the city; as it was not advisable to come now.

When he heard we have been around the city talking to people, “You should not have come,” he said.

We were actually surprised by this official asking us to get rid of our masks and gloves, when other doctors were advising us to wear them as protective gear.

Before coming to Bhilwara both of us had consulted doctors about safety measures, and were told to take all precautions.

But here, there was a different narrative. He told us wearing a mask captures the virus and all the germs close to the nose and since we can’t change them often, we might end up increasing the chance of infection by touching it.

Gloves, he added, can’t be sanitised as often as hands so they transfer germs from one surface to another.

Both of us immediately removed our gloves but decided to keep the masks on.

Skin was peeling off after chemical was sprayed

A senior police officer in the room, meanwhile, stared at us as if we were carrying the virus. Another senior officer asked us if we wanted to be sanitised, and we readily accepted.

The chemical used was sodium hypochlorite that has recently been in the news for being sprayed on migrants in Uttar Pradesh.

A person sitting near the gate gave us a generous spraying of the liquid. That, however, was hardly a good idea as the skin on Manisha’s hands were peeling off, Swagata’s blue leggings had red spots where sodium hypochlorite, a bleaching agent, was sprayed.

We came back to the district magistrate office again, as the DM had not met us earlier.

Although the officials busy with back to back meetings had no time, the DM did meet and explained to us the impressive measures they had taken to control the spread of the disease, including sealing of borders, “Anyone who wants can come in the district but they can’t leave without being screened,” he said.

As we were about to leave, he asked if we were staying or going back, to which we both replied saying we were returning,

We were too afraid to stay in a city which had the highest Covid-19 cases in Rajasthan (not as of 1 April, the epicentre has since moved to Jaipur.)

For us, it was one of the most draining assignments.

As journalists we wish to be close to the subject, meet as many people as possible, stay as long as we can in the field to get the story, but in this case we did the exact opposite.

The fear of being an unintentional carrier of the virus, spreading it to our friends and colleagues, scared us.

Manisha who had covered the Northeast Delhi riots, was not as afraid then as on this assignment. At that time she knew who she had to protect herself from, but this time her enemy was invisible, it was a virus.