New Delhi: Heavy rains over a few days in late September have caused widespread floods in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, claiming at least 148 lives. This sudden spate of rainfall marks the wettest September India has seen since 1917.

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) had predicted a dire, deficit monsoon this year, but the season has brought the heaviest monsoon rains India has received in 25 years. This, despite a late onset and deficient rainfall during the month of June.

At least 13 states, including Bihar, UP, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Assam, have experienced devastating floods this monsoon, with hundreds killed and thousands displaced.

While the rainfall was more in the September of 1917, several studies on the monsoon that year point out that the rains didn’t result in major flooding as they have now.

This points to a changing trend in the Indian monsoon, where a season’s worth of rainfall is being unleashed on certain areas within a span of days. While the quantity of this rainfall may not surpass the average by much — this year’s monsoon has a 10 per cent surplus — it is still wreaking havoc, which, experts say, is now raising questions over how India measures rains.

What happened in 1917?

The rainfall surplus for September 2019 stands at 52 per cent, 13 percentage points lower than that recorded in 1917.

The measurement yardstick has changed since — while the performance of the 1917 monsoon was calculated against the average of the 60-year period from 1901 to 1960, the current benchmark is known as the ‘Long Period Average’ (LPA), which is the average rainfall received between 1951 and 2000.

According to a study published in the Hydrological Sciences Journal in 1978, the excess rain in 1917 did not cause major floods.

“Probably, this was due to the fact that the rainfall was more or less evenly distributed and there were no localised heavy spells of rain,” the authors said in the study.

The 1921 census also does not report floods, but states that 1917 was “wet and unhealthy and a virulent outbreak of plague in the north and west of India caused heavy mortality”.

It says that the heavy monsoon in 1917 led to a malaria epidemic, and “mortality from this disease was high in almost every province”.

Both these reports note that the following year, 1918, brought a disastrous dry spell — according to the 1921 census, crops failed in Punjab and central and western areas.

“Scarcity, aggravated by the high level of prices, was declared in parts of Punjab, United Provinces, Central Provinces, Bombay and Bihar and Orissa, while agricultural conditions were equally bad in parts of the Hyderabad and Mysore states,” it said.

This monsoon

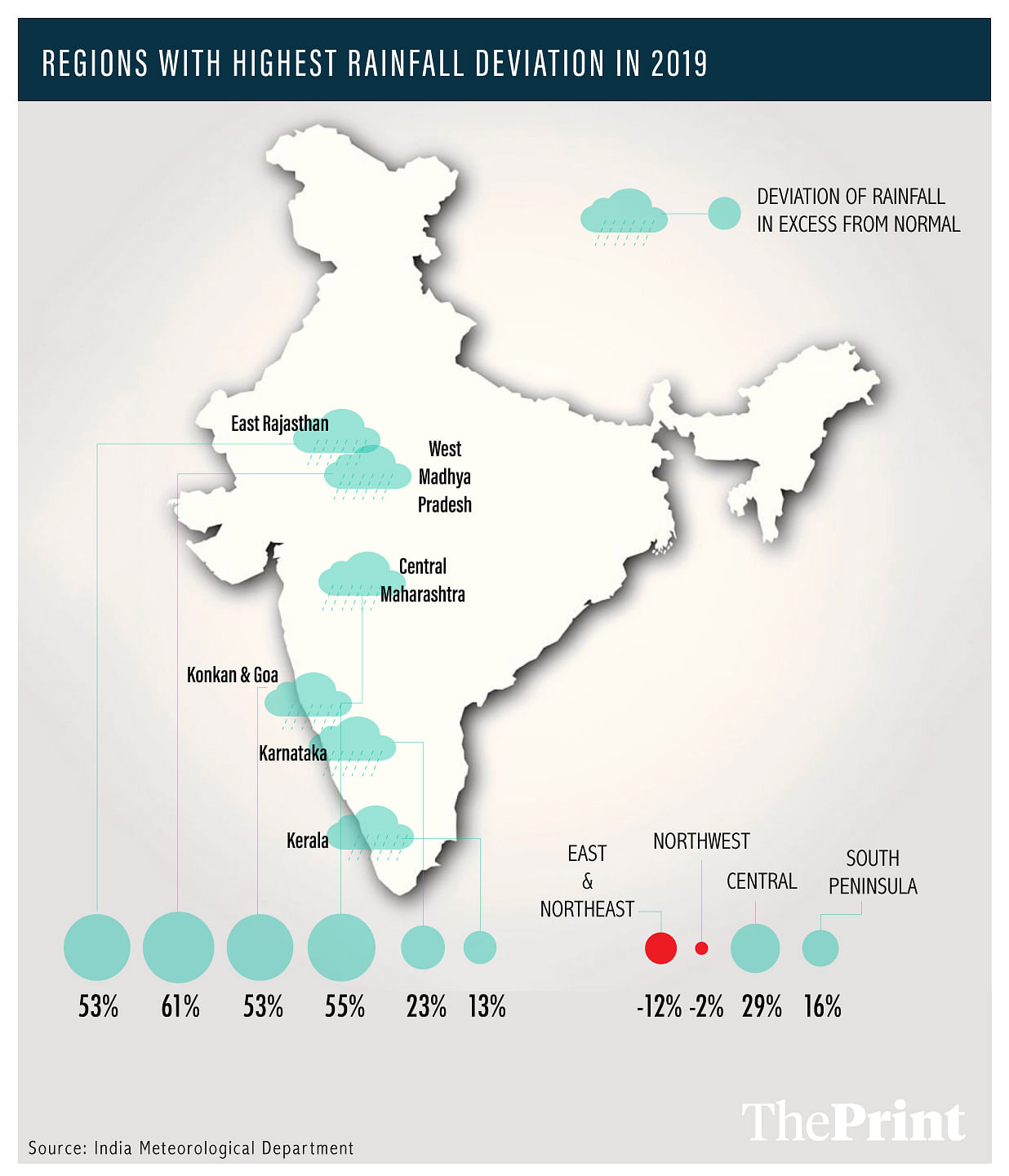

During this monsoon, according to IMD data, the rains in eastern and northeastern states were 12 per cent lower than the LPA, while places like Maharashtra experienced a surplus of 55 per cent. Uttarakhand, Bihar and Assam received lower-than-LPA rains but still faced floods.

This suggests that indicators like LPAs are no longer adequate to understand the consequences of rainfall, said Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) deputy director general Chandra Bhushan. Cities are now experiencing extreme rainfall in a very short duration of time, he added.

Bihar, for example, had reported a rainfall deficit of 16 per cent until 26 September, which changed to a surplus of 3 per cent in four days.

Researchers from IIT-Madras and IIT-Bombay who examined rainfall patterns during the monsoon months — June to September — over the past century found a peculiar trend. Their findings, released in 2016, sought to disprove the traditional notion of dry areas becoming drier and wet areas becoming wetter in response to climate change.

“The major surplus basins, such as the Mahanadi, Godavari, and Brahmani, exhibit significant decreases in rainfall,” researchers wrote in the study, published in the journal PLOS One.

“The major water deficit basin, Ganga, exhibits significant increases in rainfall…, whereas the Yamuna, Krishna and Cauvery basin exhibit decreases,” they added.

“The decrease in the monsoon rainfall in the surplus river basins, which are majorly present in the core Indian monsoon zone, may be due to the drying of rivers in these region during recent decades,” they wrote.

These patterns show that areas that previously did not have to cope with excessive rainfall may now need to be equipped to do so, with the same holding true for places not used to deficit rains.

Meanwhile, another study released by IIT-Gandhinagar researchers has suggested that multi-day flood events are likely to increase at a faster rate in the future, owing to the growth in carbon emissions and strengthening climate change.

According to the team, rising temperatures increase the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere, thereby increasing rainfall events.

Need for urban planning

Bhushan said India needed a major overhaul if it wanted to avoid the disasters rains wreak year after year.

“The civil engineering handbook, which is used to design cities, has to be revised because they were designed to deal with 100-year extremes,” he added. “But those extreme events are now taking place every five or 10 years.”

According to him, watershed areas, for example drains, are no longer able to keep up with the frequent excess rain. The unplanned growth of cities, he added, made India all the more vulnerable to floods,

“In some areas, the river bodies have also silted up. For example, in Mumbai area, Mithi has silted up and does not have the same water carrying capacities (as before),” Bhushan said.

Bhushan said India is increasingly experiencing extreme weather of all kinds — be it heatwaves, droughts or floods — and our infrastructure needed to keep up.

Odisha offers a great example in this regard. After the devastating cyclone of 1999, which claimed over 10,000 lives in the state, massive efforts were made over the years to bolster its preparedness.

As a result, the toll from Cyclone Fani, which made landfall this May and was the strongest tropical cyclone to strike the state since 1999, was less than 90.

The case of 1917 and 1918, when excess rainfall was followed by a dry spell, shows that even without climate change and global warming being a factor, India is prone to extreme weather fluctuations. Climate change can only aggravate such erratic climate patterns.

News reports of unprecedented heavy and life-threatening rain , floods continued to pour in from UP , Bihar , some parts of Rajasthan , Madhya Pradesh , during last some days in September , particularly around and on 28 and 29 September , 2019. The number of casualties so far in Bihar touched 70 while in U.P. the count crossed 100. Large number have moved to safety. There has been a huge loss of property. Some days past in September 2019 , Pune in Maharashtra was also in news for similar woes. In this context , it may be apt to refer readers to the predictive alert of this Vedic astrology writer through article – “ The year 2019 astrologically for India” – published last year 2018 on 7 October at theindiapost.com. The related text in the article reads like this :- “ July to September in 2019. These three months may also call for more care against floods , landslide , etc. Over reaction may not drag us to war or wastage”. A similar alert was sounded by this writer through another predictive article – “ World trends in April to August 2019” – brought to public domain widely in March and subsequently on 5 April 2019. A review of these alerts carried out by this writer in May 2019 , had suggested that more care and appropriate strategy in relation to , among other things , floods and damage to crops and the like in some vulnerable States of India like HP-Uttarakhand-J&K-Punjab-Delhi-Rajasthan-Bihar-Gujarat-UP , may be called for. The period suggested was from about 7 August to 9 October , while the one from 20 September ( 28-29 September ) to 9 October in 2019 was predicted to be more particular. The alert had also indicated that repulsive or repugnant smelling stuff may be at the center of catastrophe during 20 September ( 28-29 September ) to 9 October 2019. Now , more care may be called for on 5 and 6 October also in relation to multiple issues or worrisome concerns . Going by news reports , it can be said that the alert , several months prior , was meaningful.