New Delhi: Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) Chief Minister Omar Abdullah and his political opponent PDP’s Mehbooba Mufti got into a bitter sparring Friday over the Tulbul navigation lock project, also called the Wular barrage navigation project, which was abandoned by India in 1987 following strong objection by Pakistan.

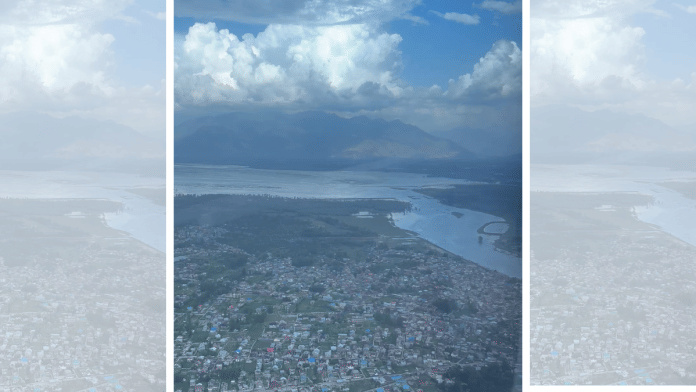

While Omar had put a picture of Wular Lake in North Kashmir on the social media platform ‘X’ and wondered if work on it would be resumed now that India has put the Indus Waters Treaty on hold, Mehbooba accused the chief minister of making “irresponsible” and “dangerously provocative” statements.

But what is the Tulbul Navigation project all about, why was it abandoned after two years even though civil works had started and how would it have helped J&K. ThePrint explains.

Over 4 decades old project

Conceived in the early 80s, work began on the Tulbul project in 1984 on river Jhelum, at the mouth of the Wular Lake, India’s largest freshwater lake near Sopore in North Kashmir. “It envisaged building a navigation lock-cum-gated control structure below the Wular Lake near Ningli to stabilise Jhelum’s water level,” said a senior government official aware about the project.

Simply put, the government proposed to construct a 439 ft long and 40 ft wide barrage with a storage capacity of 0.30 million acre feet (MAF) of water.

The barrage, once completed, would have regulated the water of the Wular Lake to maintain a minimum draft of 4.4 ft in the river up to Baramulla during the winter season. This minimum draft would have ensured round-the-year navigation over a 20-km stretch between Baramulla and Sopore.

“This would have opened up a round the year navigation route from Baramulla to Sopore. A section of the Baramulla-Sopore stretch becomes non navigable during winter months,” the official, who did not want to be named, added.

Besides, the project would have provided water and helped in firming up power generation in downstream hydroelectric plants such as the Uri I and II hydro projects in India and Mangla and other hydro projects downstream in Pakistan during the lean season.

Work started on the Tulbul project in November 1984. Civil works, including concrete piling and foundation works on the left bank, were completed when Pakistan raised the red flag.

What did Pakistan object to

Responding to a question in the Lok Sabha in August 2006, the then water resources minister Saifuddin Soz had said that Pakistan was objecting because of the perception that the project structure is a barrage with a storage capacity of around 0.3 million acre feet (0.369 billion cubic metre) and that India is not permitted to construct any storage facility on the main stem of the Jhelum under the provision of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT).

“The Indian side has pointed out that the structure is not a storage facility but a navigation facility as defined in the IWT 1960. Further, Wullar Lake gains natural storage and the navigation lock is merely a structure to regulate the outflow from the natural storage to facilitate adequate depth of water for navigation during the winter months from October to February,” Soz said in a written response to a question by Congress’ Badiga Ramakrishna.

He further said that non-consumptive use is permitted to India under the IWT. This includes control or use of water for navigation, provided these do not prejudice downstream uses of waters by Pakistan, Soz said in his response.

Under the IWT, while India has the right to use water from the eastern rivers, Sutlej, Ravi and Beas, Pakistan is allowed unrestricted use of waters of the three western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

The treaty, however, allows India storage incidental to a barrage of up to 0.01 MAF.

The government official quoted earlier said that the storage behind the Wullar barrage is estimated as 0.324 MAF, which is less than what India is allowed.

The Tulbul project was taken up for discussion by the two Indus commissioners on the India and Pakistan side. But when they could not resolve the issue, the Government of India took up the matter for bilateral settlement. However, Pakistan objected to the project saying that it would stop flow of water from Jhelum into its territory.

What is the project’s status

India agreed to Pakistan’s objections and on 2 October 1987, the project was suspended and has remained stalled since then.

There have been at least 13 rounds of discussion between the two countries but the issues remain unresolved.

A senior government official, who was involved in the negotiation of the project with Pakistan, told ThePrint that the civil works including concrete piling and foundation works on the left bank are by and large intact. “The project can be completed in four working seasons.”

Another government source told ThePrint that Pakistan’s objections stem from a deep-rooted apprehension that the navigation lock may damage its triple-canal project linking Jhelum and Chenab with Upper Bari Doab canal and that stored water might be used to deny share of water.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: IWT suspension is lawful and morally right. India isn’t weaponising water, but ending charity