Chandigarh: With the Supreme Court to take up hearing on the contentious Sutlej Yamuna Link (SYL) canal issue 19 January, Union Jal Shakti minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat has convened a meeting of Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann and his Haryana counterpart Manohar Lal Khattar to resolve the issue Wednesday.

This will be the second meeting of the chief ministers of the two neighbouring states over the issue after the Supreme Court asked Khattar and Mann on 6 September last year to meet under the aegis of the Union Jal Shakti Ministry for negotiating an amiable settlement of the decades-long issue.

The two CMs met October 14 in Chandigarh, but the meeting remained inconclusive with Mann saying his state does not have ‘a single drop of water to share with Haryana’ and Khattar later stating that it was his ‘final meeting’ over the issue.

With both states sticking to their stand, it will be interesting to see if the union minister is able to bring the two CMs reach some consensus.

So, what is the SYL canal issue that has been a bone of contention between the two states for four decades? ThePrint explains:

The water war

When the resources of Punjab — prior to the reorganisation in 1966 — were to be divided between the two states, the terms on sharing waters of the other two rivers, Ravi and Beas, were left undecided.

However, citing riparian principles, Punjab opposed the sharing of water of the two rivers with Haryana. The principle of riparian water rights is a system under which the owner of land adjacent to a water body has the right to use the water. Punjab also maintains that it doesn’t have spare water to share with Haryana.

A decade after the reorganisation of Punjab, the Centre issued a notification in 1976 that both the states will receive 3.5 million acre-feet (MAF) of water each.

Again, on December 31, 1981, Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan signed an agreement to reallocate the waters of Ravi and Beas in ‘overall national interest and for optimum utilisation of the waters’. The agreement was based on the reassessment of the available water. The water flowing down Beas and Ravi was estimated at 17.17 MAF. Of this, 4.22 MAF was allocated to Punjab, 3.5 MAF to Haryana, and 8.6 MAF to Rajasthan, by agreement of all three states.

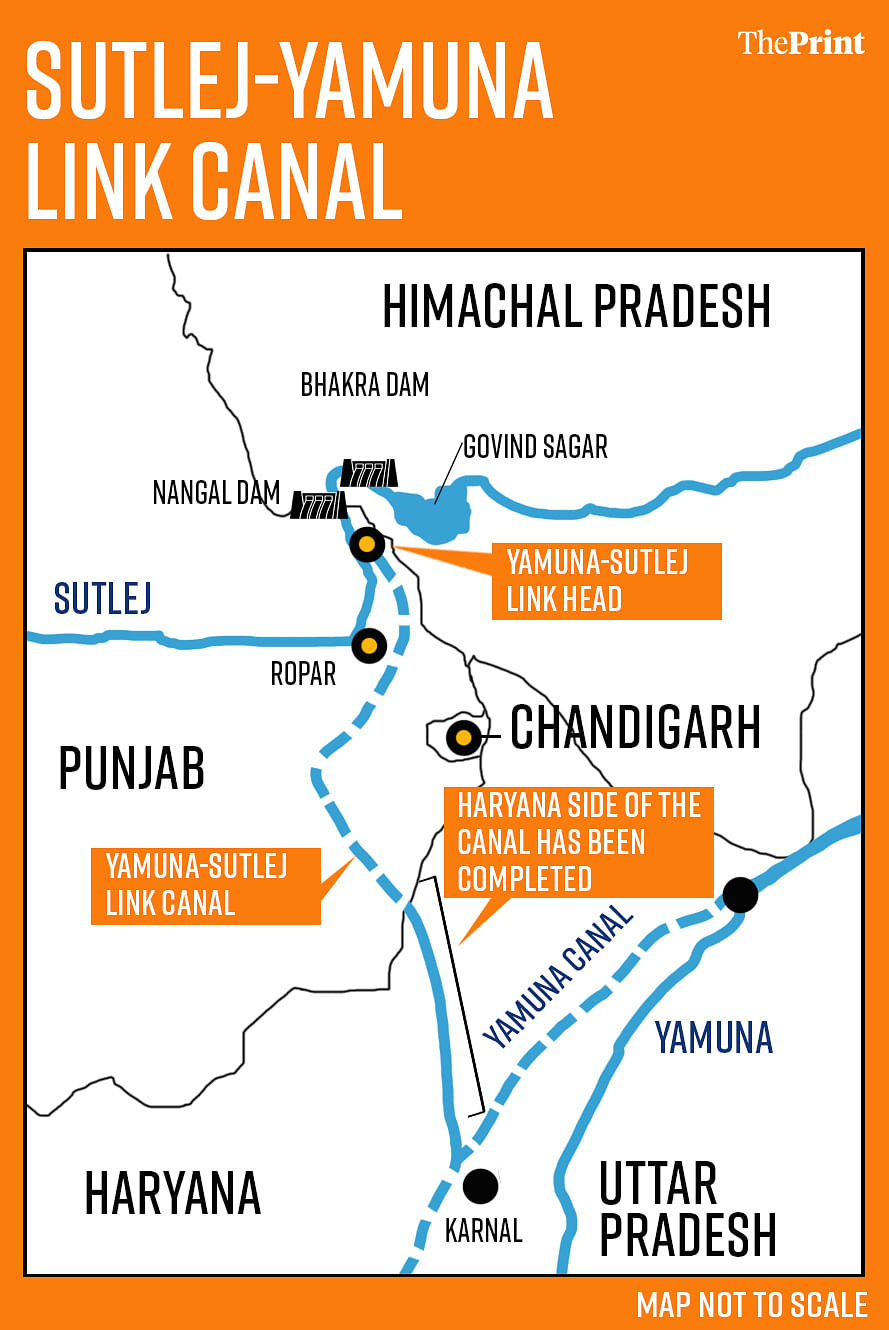

The Sutlej Yamuna Link Canal, a 211-km-long proposed canal connecting Sutlej and Yamuna, was planned in 1966 after Haryana was carved out of Punjab. While 121 km stretch of the canal was to be constructed in Punjab, another 90 km falls in Haryana.

While Haryana completed the project in its territory by June 1980, the work in Punjab, though started in 1982, was shelved due to protests by the opposition Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD).

Also Read: Polavaram dam funding gets a leg up after PM-CM meetings but project unlikely to meet deadline

The canal, stalled work & militancy

The construction work for the SYL canal was launched by then prime minister Indira Gandhi on April 8, 1982 near Kapoori village of Punjab’s Patiala district. This led to the launch of Kapoori Morcha, a protest against the SYL canal, by the SAD.

In July 1985, then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi signed an accord with SAD chief Harchand Singh Longowal, agreeing to set up a new tribunal to assess the sharing of water.

The next year, the Ravi & Beas Water Tribunal, headed by Supreme Court judge V. Balakrishna Eradi, was set up for verification of the quantum of usage of water claimed by Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan regarding their shares in remaining waters.

The Ravi & Beas Water Tribunal or the Eradi tribunal, headed by Supreme Court Judge V Balakrishna Eradi, was set up. In 1987, it recommended that the shares of Punjab and Haryana be increased to 5 MAF and 3.83 MAF, respectively.

Soon, Punjab witnessed a surge in militancy and the canal construction became a major issue between the two states. Militants killed Longowal a month after he signed the accord with Rajiv Gandhi.

Several labourers working on the project were shot dead near Majat village in 1988, leading to the stalling of construction work. In 1990, militants killed chief engineer M. L. Sekhri and superintending engineer Avtar Singh Aulakh.

Also Read: In drought-prone Kachchh, Sardar Sarovar project is ‘dream come true’. But not for all farmers

In top court

In 1996, the Haryana government moved the Supreme Court over the issue.

In 2002, the top court directed Punjab to continue work on the SYL and complete it within a year. The state, however, moved a review against the SC order but the petition was rejected.

In 2004, following orders by the top court, the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) was appointed to take over the canal work from the Punjab government. However, the Punjab Assembly passed the Punjab Termination of Agreements Act (PTAA), which abrogated all its river water agreements with neighbouring states. Then-President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam referred this Bill to the Supreme Court to decide on its legality in the same year.

The case came up for hearing in the top court in 2016. In response to the presidential reference, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court had on November 10, 2016, set aside the PTAA, a law which unilaterally terminated Punjab’s water sharing pact with Haryana.

“The Punjab Act cannot be said to be in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution and by virtue of the said Act, Punjab cannot nullify the judgment and decree referred to hereinabove and terminate the December 1981 agreement,” the top court said.

However, days later, Punjab denotified 5,376 acres of land that was acquired for the canal and announced to return it to its original owners free of cost.

In February 2017, the SC issued another order sticking to its earlier verdict that the construction of the SYL must be executed and asked Haryana and Punjab to maintain law and order “at any cost”.

“We direct that there should be sustenance of peace in Punjab and Haryana. Every citizen of this country must understand that when proceeding is going on in the court, there should not be any kind of agitation on the issue pending,” it ordered, giving both the states time till September to reach a settlement and warning Punjab not to “employ delay tactics”.

(Edited by Anumeha Saxena)

Also Read: In deadly dry Bundelkhand, Ken-Betwa link finally seems real. But critics have questions, fears