Shimla: Unable to pay a Rs 1,000 crore compensation, the cash-strapped Himachal Pradesh government has agreed to transfer 103 bighas of land to a man whose family property in Mandi was taken over by the central government in 1957, believing they had migrated to Pakistan during Partition.

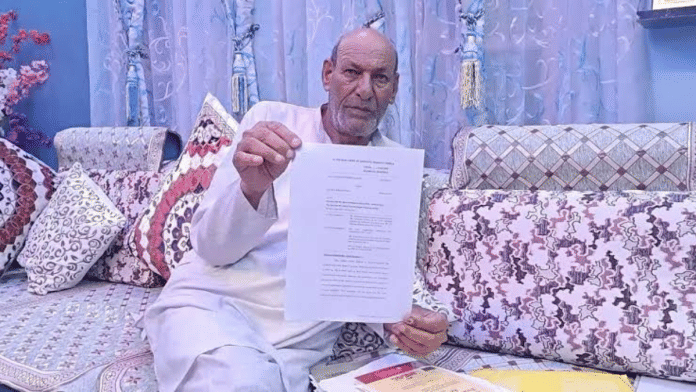

But the proposed transfer of land to Mir Bakhsh, now 68, has triggered controversy and protest by local residents and Opposition leaders, as part of the land to be transferred houses the Harabagh government garden, which was established in 1962 by first chief minister Y.S. Parmar, and is seen as a symbol of the state’s horticultural legacy.

“The government identified chunks of land after consulting Mir Bakhsh. He rejected some of the land chunks, but finally, we have agreed upon settling this case,” a senior revenue department officer told ThePrint.

Through the transfer, the government seeks to settle the decade-long dispute over the property in Mandi’s Nerchowk where the Lal Bahadur Shastri Medical College and Hospital now stands.

The property dispute, rooted in the wrongful application of the Evacuees Property Act of 1950, has seen Mir Bakhsh fight for justice since 1992, continuing a struggle his father, Sultan Mohammad, began in the mid-1950s.

Evacuee property

The saga began in the aftermath of Partition in 1947 as the central government declared certain properties as “evacuee property” under the Administration of Evacuee Property Act, 1950. These properties belonged to individuals who had migrated to Pakistan.

The Act allowed the government to take custody of such properties through a Custodian of Evacuee Property, with provisions for auctioning or leasing them.

In Mandi’s Nerchowk and Bhangrotu areas, 110 bighas of land belonging to Sultan Mohammad were declared evacuee property in 1957, despite Mohammad never leaving India, according to court cases.

Mir Bakhsh said his family remained in Himachal, but the government assumed they had migrated, seizing their land under the 1950 Act. “When the country was partitioned, many Muslims from Nerchowk went to Pakistan, but our family stayed here. The government thought we had left, and under the Evacuees Property Act, they took over our land,” he told ThePrint.

“My father kept going to Delhi to reclaim our land, but no one listened to him. Eventually, when we had no land left, we had to buy back our own nine bighas of land for 500 rupees at an auction to start afresh,” he said.

The seized land has been used by the Himachal government to build key infrastructure, including the Nerchowk Medical College (now Lal Bahadur Shastri Medical College and Hospital), a mini-secretariat, an agriculture centre, and a veterinary dispensary.

The foundation stone for the hospital was laid on 23 February 2009 and it was inaugurated as Employees State Insurance Corporation Medical College on 5 March 2014. It was handed over to the Himachal Pradesh government in 2016 following a memorandum of understanding and subsequently renamed Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Government Medical College in May 2017.

Sultan Mohammad began his legal fight by appealing to the ministry of rehabilitation on 15 February 1957. His efforts were unsuccessful. But after his death in 1983, his son Mir Bakhsh took up the cause and filed a writ petition in the high court in 1992.

The Himachal Pradesh High Court delivered a ruling in Mir Bakhsh’s favour on 9 January, 2009.

“In view of the analysis and the observations made hereinabove, the action of the respondents (the government) declaring the property of predecessor-in-interest of the petitioners Shri Sultan Mohammad as evacuee property is declared void ab initio. The respondents had no jurisdiction to declare the property as evacuee property since Shri Sultan Mohammad has remained in India and has in fact died in India,” Justice Rajiv Sharma (now retired) wrote in the judgment.

The state government challenged the ruling, first before a division bench of the high court in 2015, which upheld the single judge’s decision, and later in the Supreme Court. The apex court dismissed the government’s appeal in July 2023, reinforcing Mir Bakhsh’s claim.

“After having perused the judgment of the learned Single Judge, we find the learned Judge has held that it was categorically admitted by the State in its reply that the said Sultan Mohammad never left for Pakistan. It is not shown to us that the reply does not contain such admission.

“Therefore, the learned Single Judge proceeded to hold that the property held by Sultan Mohammad could not have been declared as an evacuee property and hence, the action of declaring his property as an evacuee property was set aside. Thus, we have to proceed on the footing that it is an admitted position that the said Sultan Mohammad never left India and therefore, he cannot be an evacuee within the meaning of the 1950 Act,” the SC noted.

The compensation claim

Following the Supreme Court’s judgment, Mir Bakhsh filed a compliance petition in the Himachal Pradesh High Court, demanding Rs 1,061.57 crore in compensation, citing the high market value of his land—estimated at Rs 15 lakh per biswa—due to its prime location along the main road in Nerchowk.

In a hearing on 31 August 2024, the high court directed the state government to act within 12 weeks. “The petitioner has been fighting for justice for years. The court’s decision is clear, and it is the responsibility of the state government to comply,” Justice Ajay Mohan Goyal emphasised.

“The land dispute, now spanning nearly seven decades, underscores the complexities of post-partition property laws and their lasting impact,” Revenue matters expert Vivek Sharma.

Unable to meet the massive compensation demand due to financial constraints, the state government proposed transferring equivalent land elsewhere in Mandi district. After Mir Bakhsh rejected the land initially offered, the state identified 103 bighas in Harabagh, the land parcel also houses the famous government garden established by former chief minister Parmar, known as the architect of modern Himachal Pradesh.

‘Sacrificing’ the garden

The choice of giving away the Harabagh garden land has ignited a controversy. Set up in 1962, the garden is a horticultural hub with 4,000 litchi trees and high-quality fruit-bearing plants. It offers a livelihood to hundreds of gardeners and workers, and also hosts an under construction Rs 12-crore mango research centre.

Local residents, supported by a struggle committee, have protested the transfer, arguing that alternative land is available and the historic garden should not be sacrificed. “We have no personal issue with Mir Bakhsh, but we will not let this historical heritage be destroyed,” said the committee.

Education Minister Rohit Thakur and local BJP MLA Rakesh Jamwal have assured protesters they will strive to halt the transfer, with Jamwal promising to raise the issue in the state assembly.

“Handing over Harabagh is unjust. It’s a legacy of our first CM. As MLA, I established a farmer training centre there. We cannot simply give away such institutions. I’ve raised this with the CM, who assured me the government will identify alternative land,” The the Sundernagar BJP MLA told ThePrint.

Mir Bakhsh, who is not the sole owner of the land declared evacuee property—his late brother’s daughter and three sisters also hold stakes—has expressed willingness to negotiate but lamented the government’s lack of engagement.

“The court has settled this matter in our favor, but the government has taken a long time to implement the court’s ruling,” he said.

Revenue matters expert Vivek Sharma told ThePrint, “The land dispute, now spanning nearly seven decades, underscores the complexities of post-partition property laws and their lasting impact. The Evacuees Property Act, meant to manage properties of those who migrated to Pakistan, inadvertently stripped families like Mir Bakhsh’s of their rightful assets.”

“As the government moves to comply with court orders by transferring the Harabagh land, it faces the challenge of addressing local opposition while delivering justice to a family that has fought relentlessly since 1956,” he said.

This is an updated version of the story

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: Kangana lands BJP in tough spot yet again amid Mandi rain havoc. Nadda in damage control mode