Nuh: Straddling a black Pulsar, 23-year-old X zig-zags through the narrow lanes of his tiny village in Haryana’s Nuh district, flinging biscuits to the stray dogs chasing his bike. Pride radiates from him—he claims he’s skilled at what he does, and the police have never caught up with him. “Those who get caught, they show off their money too soon. It’s stupidity,” he says.

With their ’emo’ haircuts, complete with red-brown highlights, swanky motorcycles, and cans of Red Bull often in hand, men like X can be seen lounging about Nuh’s villages during the day, seemingly idle. But when night falls, they get into gear. After a drink or two, they head to their workstations—hideouts in the jungles or secluded thatched huts away from the main villages.

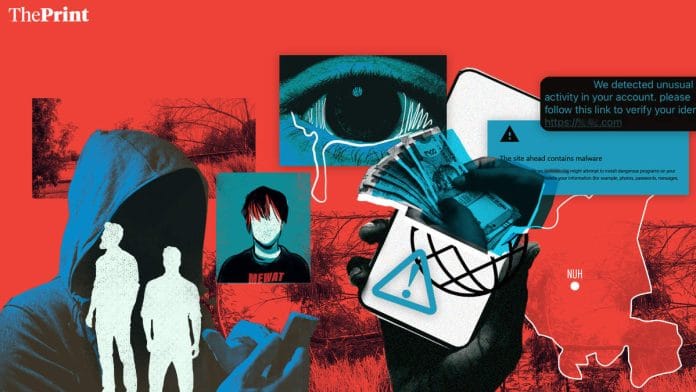

X refers to their activities as “OLX”—a platform for buying and selling items, which cybercriminals often exploit to scope out and dupe targets. However, this is merely a euphemism for a multitude of cybercrimes, ranging from sextortion to know-your-customer (KYC) scams.

“It’s easy to learn but difficult to get better. Not everyone understands how to wipe off traces,” X says, puffing on a joint. “Being greedy is bad, that gets one in trouble.”

X’s black T-shirt is emblazoned with the word “Mewat”, an assertion of his identity. It’s the name of a Meo Muslim-dominated cultural region covering about 550 villages across Nuh, Palwal, Faridabad, and Gurugram districts in Haryana, as well as parts of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

For several years now, this communally sensitive region has gained notoriety as a rival to Jamtara, Jharkhand’s cybercrime hotspot. In Nuh, cybercrime operates like a cottage industry with no true kingpins. Minimal investment and basic tech skills are enough to join the racket—a fast track to easy money and a flashy lifestyle in a region plagued by poverty and unemployment.

Like many others here, X, who didn’t study beyond Class 6, received his training in neighbouring Bharatpur in Rajasthan.

“In Nuh, these boys aren’t very educated. With basic knowledge of apps, they indulge in these activities,” explained a senior police officer in Nuh. “Sextortion doesn’t require many skills. It starts with a friend request on social media with a fake profile picture, then luring the person into a video call, recording and morphing the screen grab or video, and blackmailing them. Sometimes, they take it a notch higher by using a WhatsApp profile picture of a senior police officer.”

Haryana Police, along with their counterparts in Rajasthan, Delhi, and UP, are fighting back. Massive raids involving over 200 personnel are conducted every few months. A single raid can encompass over 300 locations, with hundreds detained and arrested.

But getting caught is not much of a deterrent either, with most suspects usually getting bail within 10 months.

“Once they have a brush with law and have gone to jail, there is nothing more they fear,” says another senior police officer. “Most of them go back to cybercrime. It is an addiction.”

Mewat is a microcosm of a larger problem, with India witnessing a massive surge of 24 percent in cybercrimes in 2022 compared to 2021, according to the latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data.

But in Nuh, which has for long struggled with poverty and underdevelopment, cybercrime has become a way of life, offering a twisted path to livelihood and the hope of some trickle-down prosperity. Even those not directly involved in rackets have little patience for “snitches”.

Poverty to cybercrime

Tucked away in the rugged Aravalli range, Nuh, with Muslims forming around 80 percent of its population, is one of Haryana’s most communally volatile districts.

It sprang to the national headlines last August after violence broke out between religious communities, but reports of communal incidents, including alleged lynchings of Muslim men accused of cattle smuggling, have cast a shadow over the region for years.

While the traditional occupations here have been farming and truck driving, these have been slowly losing favour for both monetary and safety reasons. Young men who spoke to ThePrint claimed they did not want to enter the truck driving business for fear of being stopped by gau rakshaks (vigilante cow protectors) while crossing borders.

As an alternative, cybercrime offers quick money and a way out of the poverty stemming from illiteracy and unemployment.

Travelling through the villages of Nai, Gokalpur, Khedla, Tiwara, and Bicchor, ThePrint observed scores of “new properties” rising amidst dilapidated homes and dirty lanes. Villagers claim these are testaments to Nuh’s burgeoning cybercrime “business”. Flashy watches, new bikes, and expensive Chinese mobile phones like Oppos and Vivos add to the picture.

While residents are initially reluctant to discuss the swindlers in public, they open up once convinced that it isn’t the “crime branch” asking questions. Some even describe the modus operandi and point out people with “new money”.

According to Nuh Police, the current hotspots for cybercrimes at the tehsil level are Punhana and Ferozpur Jhirka, among others. Villages frequently on the police radar include Godhola, Gokalpur, Khedla, Tiwara, Nai, Luhinga Khurd, Luhinga Kalan, Gulatata, and Mahu. Notably, the Nuh Cyber Police station was attacked during the communal violence last August during a Hindu Braj Mandal Yatra.

But by most accounts, these activities stem from deprivation and neglect.

“These boys don’t complete school. Poverty and unemployment force them into crime to earn a livelihood. The entire region is extremely backward, and reforms and socio-economic policies haven’t penetrated to fix it,” says Adil Hussain, a truck business owner from Punhana. “Once they go to jail, they come out with more impunity, realising they won’t stay in jail for cybercrimes for more than a year.”

Ironically, Hussain’s cousins, two brothers, were arrested by the Nuh police in a ‘sextortion’ case, but he claims they were wrongly accused. The men are now out on bail.

According to the Niti Aayog National Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023, Nuh, just 83 km from the national capital and barely 50 km from Gurugram, is the poorest district in Haryana. Nearly 40 percent of its population is multidimensionally poor, affected by issues related to health, education, and standard of living, compared to Haryana’s overall average of around 7 percent.

Nuh falls under the Gurugram Lok Sabha constituency, which will got to polls along with the rest of Haryana’s 10 seats on 25 May.

Also Read: Nearly half of Haryana’s Muslims live in violence-hit Nuh — district with higher fertility & poverty

White lies & ‘snitches’

X entered the world of cybercrime some three years ago, although he claims to have steered clear for a few months now.

“There was hardly any other option. This was easy and quick money,” he says.

As X narrates his story, villagers surround him protectively. It’s an unspoken agreement in Nuh—many don’t consider these activities crimes, save for a few dissenters. Some even check if he feels uncomfortable with the interaction.

“Our people love us and would do anything for us. I too help them out with daily needs when they ask. We are a community,” X says, noting that some get jealous and are “snitches”.

“Villagers don’t want to cooperate with the police. They consider arrests as an atrocity, especially since the victims aren’t from Nuh or Mewat region,” another senior police officer says.

Yet, some villagers are fed up, with a few even becoming police informers.

“The fast money makes them lose their minds. They drink and create a ruckus in the evening, but we can’t complain because most villagers protect them,” said Ahmed, a resident of Tauru.

But X is sanguine. “I might end up in the police’s net soon but I know I will get bail. Everyone does. We aren’t killing people,” he says.

Nimble operations, changing hideouts

One of the more popular cybercrime enterprises in Nuh is “OLX scams”, where perpetrators use photos of real items listed for sale to defraud buyers, taking money in advance. Sometimes, they also advertise alcohol for home delivery in Delhi, despite this being illegal there.

All that’s required are fake SIM cards, Aadhaar cards, and bank accounts. Unlike Jamtara’s sophisticated operations, cybercrimes in Nuh are as basic as telling a “white lie,” according to police officers.

Y, an accused out on bail in a sextortion case, tells ThePrint that some only moonlight as cybercriminals while keeping their day jobs.

“During the day, we do our daily work. Some of us are electricians, run shops and even farm,” he says. “In summers, when the sun goes down, we go to the kothris (outhouses) made in the farms or sit under trees in the jungle.”

A stash of SIM cards, an alert system, and a quick getaway plan are essential, according to him.

“One SIM is used only once and destroyed. The SIM cards are mostly from Delhi, UP, and Rajasthan. When the police get alerted, we also have a system that alerts us. We then go away to Rajasthan, Gujarat, or wherever else we have friends and relatives,” he adds.

Y took ThePrint to some of the hideouts where young men aged 17-30 sit and chat during the day, discussing daily operations.

In their makeshift dens, covered with hay and situated under dense foliage, these men start by screening Facebook and Instagram on their Chinese handsets. They then decide whom to talk to and scam. Beginners start with OLX frauds, while experts move onto sextortion. If a target doesn’t pay up within two days, they move on.

Once a “big deal” comes through, they lay low for a while, sometimes breaking and disposing of their phones.

The dens of these cyber-crooks are never near their homes. The hideouts also keep changing—from village to village and even across districts. While villagers know where the fraudsters operate, they tend to not cooperate with police during raids.

If the police discover a hideout and make an arrest, X says it’s only “wise” to sever ties with other members of the cybercrime team. “I never store anyone’s number on my phone,” he says.

‘Only pawns of a big game are arrested’

The dusty quiet of Ranota, a tiny village in Nuh, was shattered in November 2023 by the screech of police vehicles as brothers Waseem and Qasim were hauled off on accusations of sextortion. A month later, both got bail and continue to protest their innocence.

The brothers allegedly used “nude photographs of women” and impersonated “WhatsApp IDs” to trap unsuspecting victims on social media and extort “huge” sums of money from them, according to court documents.

However, their family members, including 78-year-old Rasheed Ahmed, insist the men are innocent.

While Qasim, 21, is still studying at the local madrasa, Waseem, 23 drives a JCB in Chhattisgarh.

“He was here for a holiday for around 12 days and the police arrested him. Why will someone who doesn’t live here do it from here when they visit?” asks Rasheed.

Qasim also maintains his innocence, claiming he doesn’t understand technology well enough to carry out such activities. After their arrests, however, the police seized an Oppo mobile phone worth Rs 30,000 from them.

“We weren’t questioned. The police says that they would let us go but instead they sent us to jail,” says Qasim.

While picking up the men, the police had also detained their younger brother but he was let off as he was a minor.

“It’s true that youth here in Nuh are involved in OLX scams and other cybercrimes but these boys weren’t,” Ranota sarpanch Khurshid Ahme tells ThePrint. “Look at their house! If they had money, wouldn’t they have a bigger house? Sometimes the ‘informers’ give wrong tips to the police for their personal vendetta.”

In another village, Shahpur Ghagas, 25-year-old Dilshad Mohammed also vehemently protests his innocence. He was arrested in January and granted bail 19 days later. His father Nazar Mohammed is a truck driver while his brother Rahul does odd jobs.

“I work as an electrician. I had a large shop before Covid but due to the lockdown I couldn’t afford the rent and now I have rented a smaller shop,” he says. “We would have a bigger house if we did cybercrimes. We could also afford an AC then instead of managing with one cooler.”

However, his mother Naseema says Dilshad was arrested after a tip-off from an informer from another village, alleging that the police only go after the small fry.

“Families have grown very rich through these crimes. No one is arresting the main leaders of these gangs. Those arrested are just pawns of the big game,” she says.

At the intersection between Ranota, Khedla, and Gokulpur villages, large groups of men sit under the shade on charpoys, smoking beedis and marijuana.

“There’s no employment here, and we’re not educated,” one of them says. “Not all of us are involved in these activities, and we try to stay away from those who are. But you’ll hardly find anyone who doesn’t know someone involved in this business. There are just no other viable options left.”

Another man, seemingly intoxicated, interjects. He claims informers often provide false information, leading to wrongful arrests.

“If you want to find the real perpetrators, trace the newly built properties, not necessarily those who were arrested,” he says.

In Nai and Tiwara, neighbouring villages known as hotbeds of cybercrime, silence reigns. “If anyone is seen talking to an outsider, the villagers boycott them,” says a resident of Nai. “Everyone thinks they are informers.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Sand miners are the new narcos. Rajasthan gangs offer cash, career, swag