Chandigarh: Outside a tiny window of an urban community health centre in Jalandhar, which houses the Outpatient Opioid Assisted Treatment (OOAT) clinic run by the Punjab government, about a dozen young men line up to acquire Buprenorphine and Naloxone—drugs used in fighting narcotic addiction.

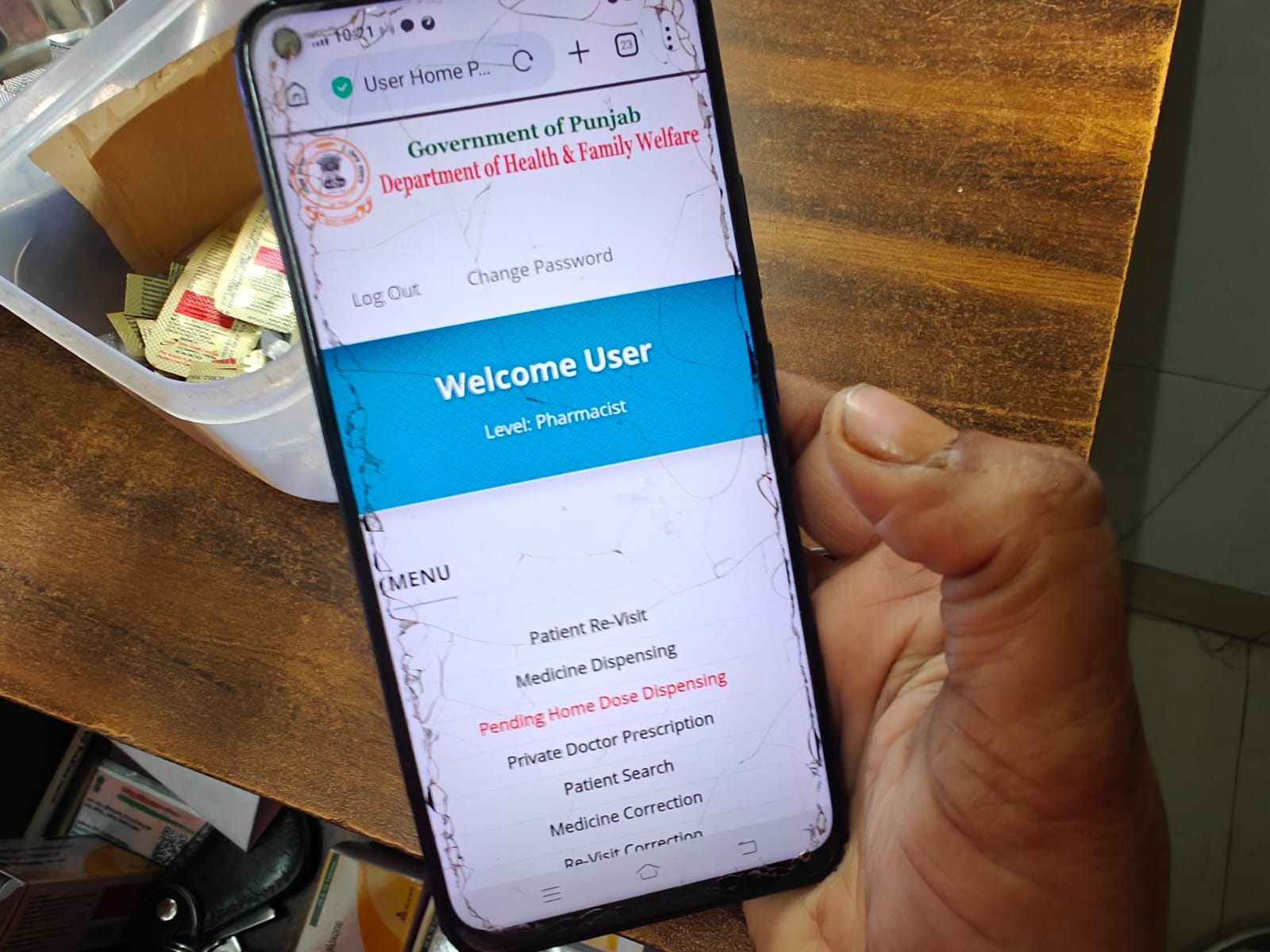

At the clinic, two women run the medicine distribution programme. By 11 am on a Friday in March, they have already dispensed medicines for 200 individuals. As one of them goes through the distribution records on a computer newly provided by the government, the other manages the process on her personal mobile phone. “We didn’t have a computer till now to maintain records. Mobile phones are the way to go,” one of them says.

Senior doctors involved in the process also confirm that the state health department portal—through which the de-addiction medicine is dispensed—is often operated via the staff members’ personal devices.

One of the men in the queue outside tells ThePrint that he has been consuming these medicines for at least three years. “I have been taking this to maintain my health. Leaving this even for a few days gives me a bodyache and headache. I can’t sleep without consuming this.”

The scene at the health centre is a peek into the challenges the Bhagwant Mann government faces with respect to its new offensive against drug addiction and the ecosystem that surrounds the menace—‘Yudh Nasheyan Virudh (war against drugs)’ launched at the end of February.

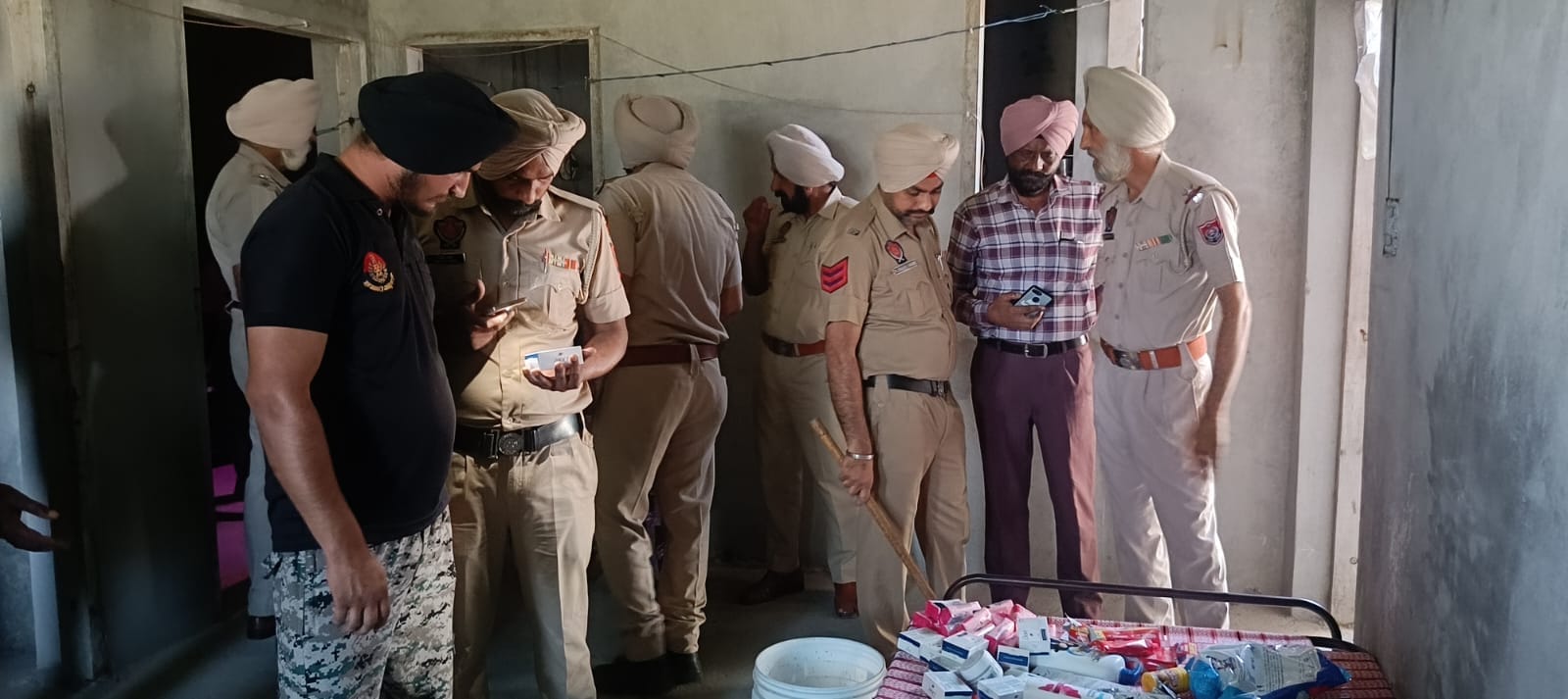

The three-month period set under the campaign to eliminate the problem is not the first such deadline, but all components of the state government are on a “war footing”. Punjab Police have arrested 4,650 “smugglers” and registered 2,765 cases, while recovering 185 kg of heroin and 89 kg of opium in the month of March, according to a statement. Heroin (chitta) and opium (afeem) are among the most consumed drugs in the state.

While the authorities have gone to the extent of demolishing the houses of those accused of involvement in the drug business, senior doctors and several government officials point out the key challenges that this approach hasn’t managed to solve. While a police crackdown is limited to choking the supply of drugs, the demand remains intact, there are gaps in the necessary infrastructure and manpower to carry out effective deaddiction programmes, and there is a dearth of reliable data.

The adoption of a similar approach in the past has failed to yield positive results, they say.

“We have seen this trend of throwing peddlers into jails in the past. It has happened on at least two occasions under the previous governments. Did it change the ground reality? Police action is essential as it curtails the easy availability of drugs on the street, but it can be successful only if the deeper problems of the society are addressed,” a senior Punjab government official involved in previous anti-drug campaigns conceded.

Punjab reported 33,000 cases related to consumption and selling of drugs between 2022 and 2024, second only to Kerala, which reported 85,334 cases, according to data compiled by National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). During the same time period, Punjab reported more than 250 deaths related to drug overuse. However, officials admit that the number could be higher.

In Part 1 of this series, ThePrint took a close look at the proliferation of illegal de-addiction facilities in the state.

Also Read: Beatings, forced labour, starvation—Haryana rehab centres are torture chambers

Gaps in de-addiction system

Days before a high-level meeting with Chief Minister Mann at the planning stage of the ‘war against drugs’ campaign, deputy commissioner-level officers of the state were alerted about a possible surge in the number of patients turning up at de-addiction centres and OOAT clinics. The reason, according to Chief Secretary K.A.P. Sinha, was the inevitable crackdown on drug supply chains by law enforcement agencies.

A senior civil servant recommended that the infrastructure and equipment be ramped up to deal with the surge. On the ground, however, the communication to upgrade the healthcare system created mixed feelings.

Another civil servant involved in the planning tells ThePrint that at least 30 percent more patients were expected to come to de-addiction centres after the curtailment of supply and that work is underway to raise intake capacity at government-run centres. Punjab has 36 state-run de-addiction centres with an overall capacity of 660 beds.

But the problem is too deep-rooted to be solved in the matter of a few months—let alone days—government doctors and officials say.

The de-addiction campaign in Punjab hinges on three broad pillars—de-addiction centres, rehabilitation centres and OOAT clinics.

Depending on the condition of a patient seeking help at government de-addiction centres, the doctors, including a psychiatrist, decide the course of treatment. Patients with a history of seizures and severe opioid dependence are referred for inpatient detoxification at the centre. After the detoxification phase, which lasts for around 15 days, comes the three-month long rehabilitation programme, following which patients can be inducted into OOAT for treatment via the OPD route.

But this system has multiple gaps and limitations. For instance, officials say, the standard operating procedure for running an OOAT clinic includes mandatory presence of two medical officers with MBBS degrees, two staff nurses, one counsellor, three-four peer educators, a data entry operator, and a class IV employee, along with a security guard.

According to records from two districts, only two psychiatrists are available against the requirement of over 30, with two-thirds of the positions of medical officers lying vacant. With respect to counsellors and peer educators, there is 80-100 percent vacancy across centres.

Overall, the Punjab government has 51 psychiatrists employed in public health facilities, with only three-four each catering to big districts, like Jaladhar, Amritsar and Ludhiana. In smaller districts, such as Tarn Taran, Gurdaspur, Faridkot and Bathinda, only one psychiatrist manages the entire load of patients.

Every OOAT clinic must run from a different facility, with separate rooms for medical officers, staff nurses, counsellors, data entry operators, and a designated space for a waiting hall for patients.

“Forget complying with the SOPs. We don’t even have buildings for OOAT clinics. We operate from one room allocated in a primary healthcare centre or community health centre in urban areas,” a district in-charge medical officer tells ThePrint.

Any individual with a history of addiction approaching OOAT centres is registered in a central database using a biometric system, and assigned a unique identification number (UIN). Then the counsellor and medical officer assess the patients to diagnose the extent of addiction and drug dependency. The registrations and provision of medicines are done via a portal of the state’s government’s health department, which collapses almost every day.

“We are not equipped to deal with around 2 lakh patients daily as the portal breaks down completely—sometimes for hours—leaving us helpless. Has any work been done behind the scenes to strengthen the portal to manage the extra load that the government expects the current campaign to create?” a senior doctor remarks. “The answer, I am afraid, is no.”

State government data accessed by ThePrint indicates that the number of people turning up at de-addiction centres after 23 February—up to 10 March—more than doubled, versus before. The figure increased to 594 from 274 in the fortnight preceding the police crackdown, with the average number of 12 persons per day surging to 40 per day.

Another district-level medical officer says that operating OOAT clinics is fraught with risk, considering the violent nature of withdrawal symptoms that some drug addicts go through. Many of these are run at primary healthcare centres, where vaccination drives are underway in the adjacent chamber, he adds. “Incidents of brawls and violence among addicts are not uncommon. Have we measured the estimated number of addicts who could be coming to the centres?”

A top official says that proposals for security infrastructure have been taken up by the government, but there is no keenness on provision of police security at OOAT clinics.

“These clinics have been set up in remote areas to help people reach out to the government and get cured. Permanent deployment of police officers would deter them from coming forward due to fear of criminal action. The government is actively considering providing private security cover to make female staff safer at the clinics in remote areas,” the official says.

Another doctor talks about the mismatch between the human resource availability and the government’s objectives. Efforts should have been taken to mobilise the workforce by carrying out recruitment drives to fill positions of psychiatrists and medical officers, before launching the anti-drug drive, he says.

On the contrary, Dr Charanjit Singh, a medical officer deployed at the de-addiction centre in the government medical college in Amritsar, says that there is sufficient infrastructure to cater to the number of patients coming to de-addiction centres. “Enforcement by police is critical to the success of the campaign. Without curtailing the supply, there is no amount of workforce that can tackle the issue we are facing,” she adds.

Former Punjab chief secretary Karan Avtar Singh, who led the government’s anti-drug initiative under Captain Amarinder Singh’s government that came to power in 2017, says that Punjab or any government looking to achieve a target like this should have a dedicated workforce. “The bureaucracy is already overwhelmed with different aims and objectives from multiple campaigns and programmes. Achieving outstanding results through the same approach won’t be possible without creating a dedicated team, whose only objective is drug eradication,” he tells ThePrint.

The retired civil servant says that the issue of low manpower, especially psychiatrists, has persisted for a long time in the state, and that deeper reforms are needed. “Punjab has only three medical colleges with only a few PG seats for psychiatrists. We need to increase this number for the government to have a richer pool of doctors, who are the backbone of the de-addiction regime. A lot of these reforms have to take place at the Central level.”

Moreover, officials say, many doctors do not turn up to actually join government services despite applying. “13 doctors with MD, Psychiatry qualification have applied for government services recently. Let’s see how many of them join,” a senior official says.

Shot in the dark

The absence of reliable data is another major worry.

The former chief secretary says that doctors in Punjab have always been apprehensive about the use of Buprenorphine for de-addiction due to evidence of relapse in patients as well as the possibility of them getting addicted to the medicine itself.

While the de-addiction programme under Amarinder Singh had some impact for the first few years, he adds, it could not sustain the success for long due to lack of data on relapse.

“Absence of data on relapse was a major hindrance in forming a workable policy. We get to know about the relapse, only when the person turns up with it. We don’t have any mechanism to record relapse, which is a two-pronged problem because first, the person has gone back to square one, and second, he is not coming out for treatment,” he says.

A district-level psychiatrist tells ThePrint that the government is contemplating the introduction of a dedicated software to capture the incidence of relapse among patients registered with the government.

Doctors also flag concerns about patients getting addicted to Buprenorphine instead. But Dr Atul Ambekar of National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre and Department of Psychiatry at All India Institute of Medical Sciences says that even if they continue taking the medicinal drug for life, it should not be seen as a problem.

“It is a common misconception that people are getting addicted to medicines. Opioid dependence is a chronic illness, which requires taking medicines for a very long period—in some cases, even life long. There are many other health conditions that require long-term treatment—diabetes, hypertension, depression, hypothyroidism to name just a few,” he tells ThePrint.

“We will have to accept that if patients are kept away from illegal and dangerous drugs like heroin, and lead a healthy and productive life while taking an agonist medicine like buprenorphine, it indicates that the treatment had a good outcome.”

Ex-chief secretary Karan Avtar Singh also recommends a public-private partnership model to enhance the performance of de-addiction centres across the state, instead of leaving the private sector to operate separately. “Private players should be partnered with for a fixed payment from patients, and a performance-based payout from the government for demarcated geographical areas. Their payment should be linked to performances in terms of the number of patients treated successfully at their centres, instead of the current model of them working independently, and charging different prices from different patients,” Singh suggests.

On the other hand, Dr Ambekar emphasises that the success of Punjab’s de-addiction campaign depends on the success of its OOAT clinics. Punjab has a total of 529 government-run clinics across the state.

He says that Punjab’s initial strategy of dealing with drug abuse issues through a large number of de-addiction and rehabilitation centres has not been the best way forward, considering the high prevalence of opioid dependence which is a chronic, relapsing disease that requires long-term outpatient treatment.

“Short-term inpatient treatments (typically provided in de-addiction centres) have limited evidence of effectiveness. Outpatient clinics providing agonist maintenance treatment was our major recommendation for the state in 2015,” he says. “Subsequently, Punjab initiated a large-scale programme of Outpatient Opioid Agonist Treatment, which is currently catering to the needs of lakhs of patients with opioid dependence. While we have not been involved in any formal evaluation of this programme, going by the large number of patients accessing it, it is obviously popular.”

He also, however, suggests scientific evaluation of OOAT clinics to further improve performance of the prevalent system. “It would be very useful to have this programme scientifically evaluated so that required improvements can be made, and more importantly, other states may learn and replicate.”

Also Read: More Indians getting hooked on opioid painkillers. Doctors warn of possible ‘pharma opioid epidemic’

‘Curbing supply alone won’t work’

The clarion call to launch “war on drugs” is not the first anti-drug effort by the government led by Aam Aadmi Party that had stormed into power in Punjab with 92 out of 117 seats in the 2022 assembly elections. After hoisting the Indian Tricolour on Independence Day in 2023, Chief Minister Mann had declared that the deadline to eliminate drugs from the state was 2024 Independence Day.

While the government has a good record of crackdown in cases of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 with around 85 percent conviction rate, experts have long maintained that the fight against addiction has largely been political, and no party in power has been able to work out a solid strategy.

In the period between the AAP government taking office and the onset of the current campaign, Punjab Police made 47,700 arrests and filed 32,600 FIRs, seizing 3,200 kg of heroin, 2,730 kg of opium, 132 tonnes of poppy husk, 3,234 kg of ganja and 55 kg of ice.

But there are those who point out that the approach of containing drug menace solely via police action has been tried previously by the governments led by Shiromani Akali Dal, Congress, too, with no visible impact on ground.

“Thousands of people have been arrested and sent to jail on the grounds of peddling drugs for more than a decade now. Has it helped one bit? Has it changed the ground reality?” Dharamvir Gandhi, Congress MP from Patiala, says. “What the government has tried to do with the police is choke the supply of drugs. They have been either completely oblivious to the demand side of the economics, or have not done enough to curtail demand for banned contraband.”

Former chief secretary Singh also agrees that all governments—in the past and present—have tried dealing with the issue as one of enforcement. The issue of drugs, he says, is more social and medical in nature.

Dr Ambekar asserts that policies should strike a balance between controlling supply, reducing demand and harm caused by the banned substances. “In general, ‘war on drugs’—which has been fought globally on many different occasions—is largely an inspirational slogan. Data suggests that addiction is a problem which cannot be solved with brute power or law enforcement authorities alone. Indeed a large number of international experts have proclaimed that such a war has failed.”

According to a senior police officer, police or any law enforcement agency can at best seize 10 percent of the contraband, which is not enough for the objective that the government is trying to achieve.

“Annual recovery of heroin is around 1,200 kg in Punjab, but that would amount to only 40 days of consumption. If we continue our crackdown with the same intensity, it could go up to 3,000-4,000 kg a year,” he tells ThePrint. Heroin is the most consumed drug in Punjab, with around three lakh addicts out of the 12 lakh drug registered addicts in the state.

“Pakistan earns approximately Rs 9 lakh from one kg of heroin, which is sold in the drug market for Rs 30 lakh in the span of one week. There is no alternative that can earn youths this amount of money in such a short time. Hence, they latch on to the opportunity,” another police officer explains. “Police can heighten surveillance for some months or years, but this is a vicious cycle that will keep turning till the demand problem is solved, which will require large scale changes in the society against drugs.”

One police officer tells ThePrint that the Anti-Narcotics Task Force has shared a list of 1,849 major drug traffickers and 755 hotspots of drug business with police chiefs in the districts, but the role of police is “limited to only choking supply lines”.

Retired Indian Police Service officer Shashi Kant, who has been a vocal critic of Punjab government’s drug policy over the years, says that the current approach is no different from past exercises, where people were arrested and put in jail, with no infrastructure for their de-addiction and rehabilitation.

“How many of them can be put in jail? Is there even a fair chance they would come out clean? Do you have a proper mechanism in place to deal with their withdrawal symptoms? How many jails have proper facilities for de-addiction? This policy of mass arrests is not going to help solve the issue,” he remarks.

Senior police officers say that the raids are not entirely focussed on sending people to jail, and that those found with small quantities of narcotics are also being sent to de-addiction centres based on their consent. Section 64-A of NDPS Act provides legal immunity to individuals caught with small amounts of narcotics, if they voluntarily seek medical treatment for de-addiction at recognised government facilities.

According to government records accessed by ThePrint, within 14 days of the launch of the ongoing campaign, 67 people were sent to de-addiction centres under this provision, out of the 2,806 arrested.

While officials in the prisons department claim to have enough space to accommodate the newly-arrested individuals, they do not deny the fact that jails are running at full capacity—housing around 30,000 prisoners. “We have sent proposals to set up full-fledged de-addiction centres across all major jails and it is in active consideration by the government. Currently, we have de-addiction centres in Faridkot and Ferozepur jails. We are planning to set up across all 10 central jails in the state,” one official says.

‘Switching from greater to lesser evil’

While there are challenges to the de-addiction and rehabilitation regime in place in Punjab, there is also a school of thought that views NDPS Act as the biggest hindrance.

Among the critics is Patiala MP Gandhi, who advocates for decriminalisation of naturally cultivated drugs, such as poppy husk, opium and marijuana. He claims that synthetic drugs made their way into schools, colleges and homes in Punjab only after the enactment of NDPS Act, which criminalised the drugs.

“When NDPS criminalised stimulants, which were part of traditional culture in Punjab, people first got hooked on pharmaceutical products, such as cough syrups. It’s high time the government decriminalises use of these natural products to solve the drug menace,” he says. “These stimulants were addictive, but never hazardous to health, like heroin or fentanyl. People used to take it to increase their energy and relax after working in the fields.”

Senior officials involved in the de-addiction programme at district level see merit in the idea. “The data on the number of individuals addicted to synthetically produced drugs, their overall health status, compared to those who used to take these natural stimulants, tells a story,” a senior civil servant says.

“Even if people addicted to synthetic drugs can be made to switch to natural stimulants, it would be a considerable transformation,” he concedes, before adding that a “revolution” is required to achieve that purpose.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Smack & ‘solution’ are consuming Delhi’s homeless kids. For them it’s a refuge

Udta Punjab is a headache for the entire nation.