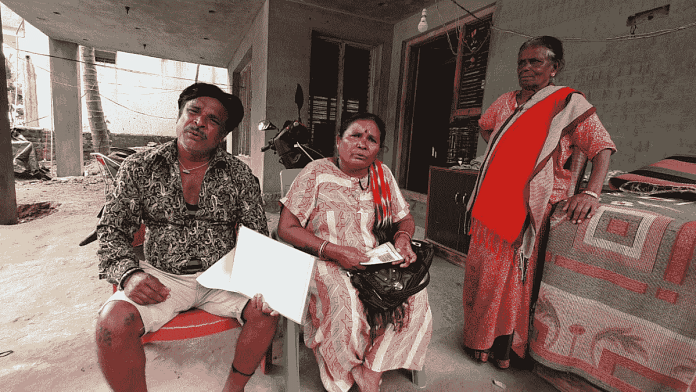

Pakshirajapura, Hunsur: In Pakshirajapura, a small hamlet at Hunsur in Karnataka’s Mysuru district, 60-year-old Papachi P. sits on an orange plastic chair outside his house — a half-finished cement structure bereft of any paint. All around are signs of construction abandoned midway — the partly dug holes surrounding the house’s main pillars, the debris of construction materials that line the front yard and even the uneven ground on which Papachi’s chair stands.

The main structure of the house was completed four years ago, Papachi told ThePrint. But ever since, there hasn’t been enough money to complete the job.

It’s been more than a month since Papachi, his 26-year-old nephew Devan and his 21-year-old niece-by-marriage Sanjana returned from a civil war-torn Sudan, where they, like many others in the village, had gone to sell the traditional medicines they make.

This hamlet of around 500 people is home to the Hakki Pikkis, a nomadic tribe who are known for their herbal medicines. For a few months each year, several inhabitants of this hamlet travel abroad to Africa, or central or Southeast Asia, where their medicines are particularly in high demand.

But the civil war in Sudan — where the Sudanese army and a paramilitary group called the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have been fighting since April — has thrown a wrench in their works. Personal debts are mounting, and it’s getting harder to make ends meet.

“This is the only profession we know and have been pursuing since the time of our forefathers. Now, we don’t have the money, have debts up to our nose and no one will fund our next trip,” Papachi P. told ThePrint.

On 18 April, Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah, who was then the Leader of Opposition, tweeted to highlight the plight of at least 31 members of the tribe who were caught up in the Sundan crossfire.

It is reported that 31 people from Karnataka belonging to Hakki Pikki tribe, are stranded in Sudan which is troubled by civil war.

I urge @PMOIndia @narendramodi, @HMOIndia, @MEAIndia and @BSBommai to immediately intervene & ensure their safe return.

— Siddaramaiah (@siddaramaiah) April 18, 2023

This led to a war of words between him and external affairs minister S. Jaishankar, with both sides blaming the other for “politicising” the issue.

Three days later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi chaired a high-level meeting to review the situation.

Many villagers that ThePrint spoke to said they hid in bathrooms in Sudan and got by on scraps of food they found on the streets. In the first week of May, most of them returned home.

But for many, their problems had only just begun. For decades, those involved in the medicine trade would borrow money to travel abroad and usually pay them off through their sales, Papachi said.

But even before the Sudan war, business had been poor in the last few years, mainly because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant travel restrictions. The strife in Sudan has only added to these losses, and for many, led to a mountain of debts.

Like others in her village, 70-year-old Sirkus Bai has been facing financial difficulties.

“We were brought to this village 65 years ago and this is the only profession we know,” Sirkus Bai told ThePrint, pleading for some financial help from the government to make ends meet. “We collect herbs, roots and plants from the forest and make medicines out of them.”

Who are the Hakki Pikkis

According to the Union education ministry’s Scheme for Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages (SPPEL), Hakki means “bird” and Pikki means “to catch” in old Kannada.

Classified as a Scheduled Tribe in Karnataka, the Hakki Pikkis speak an Indo-Aryan language that has a mix of Gujarati, Hindi, and Kannada. Both the Indian government and UNESCO have listed the language, which scholars and linguists call ‘Vaagri’, as endangered.

It was in the 1970s — when bird hunting was banned — that this nomadic tribe of bird hunters were rehabilitated in this hamlet, the Times of India reported.

“The Hakkipikki community migrated from the Northern India population (sic) which is about 8,414 (2001 Census) is found in Karnataka. The population is mainly concentrated in Shivamogga, Davanagere and Mysuru district of Karnataka. The alternate names of the Hakkipikki are Haranashikari, Pashi pardhi, Adavichencher and Shikari in Karnataka as per the available materials,” SPPEL says in its website.

Nobody in the village quite remembers who discovered viable markets abroad or how, but many agree that it was found at least two generations ago.

Each trip abroad costs Rs 3-4 lakh, said Papachi. Travellers have to pay for visa, air tickets and accommodation for a few months. In order to make good sales, they often have to travel deep into foreign lands.

Travelling and trading abroad also means being able to communicate with the locals — which is why most people in the village speak at least two international languages, if not fluently, then just enough to get by.

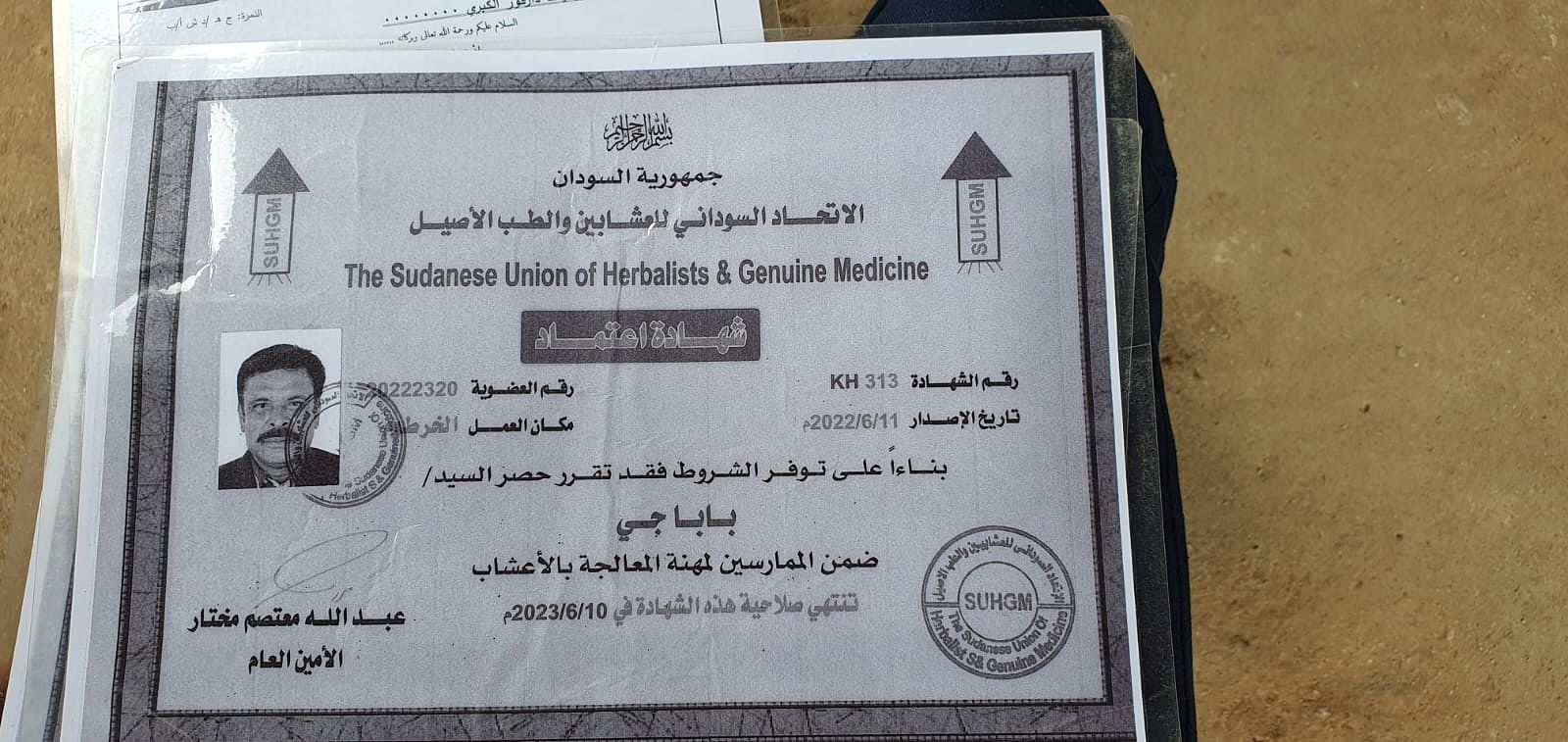

They also get certified as herbal medicine-makers abroad, but not in India.

“Most modern medicines are unaffordable in foreign countries and in our case, we apply it on them and when they see results, they ask for more and do the marketing for us,” 29-year-old Prabhu Devan told ThePrint.

‘5 paise loans’

In the quaint hamlet of Pakshirajapura, there are at least three well-established “therapeutic centres”. Dotting the walls around the village are several posters of women with thick hair extending almost to their knees.

At Papachi’s house, his 21-year-old niece-by-marriage Sanjana, at the urging of her husband Devan and aunt Mimi, reaches back and unwinds her black knee-length tresses to show us the “power” of the herbal medicine they make.

The ‘Adivasi Herbal Products’ that Papachi and his family sell are aimed at curing gastric illnesses and diabetes and are also meant for weight loss and hair growth. Sanjana’s long hair is often used in the pamphlets and posters promoting “the cure” for baldness, the family says, adding that her hair is also used to make wigs.

Beside her, Devan describes how the medicines are made. “We make the medicines by boiling it in freshly pressed coconut oil. We make powder out of it and carry it with us during our travels,” he told ThePrint.

A bottle of their hair-growing oil fetches Rs 200 in India but abroad, the same product can go for as much as Rs 2,000 abroad. The herbs used in making it are handpicked from the mountains around Baba Budangiri, a range of hills nestled in the heart of the Western Ghats located in Chikkamagaluru district, he said.

In a good year, each household makes around Rs 5-6 lakh. But times are hard now, and since travelling abroad is no longer an option for many, inhabitants of Pakshirajapura are now trying to promote their products within India.

For this, they use social media to post videos and other promotional material. “We have two courier centres here in the village. We also take help from anyone we can and post videos on YouTube to market our produce,” Papachi said.

But this is usually insufficient, forcing many to turn to ‘idhu paise’, or 5 paise loans. Offered by money lenders, the loan has an interest rate of 5 paise/day on every rupee taken. This comes to Rs 5,000 a month for every lakh borrowed.

“Everyone here is drowning in debt,” said Papachi, then turned philosophical. “Sikkre shikari, sikhllila andre bhikari (If we get, its gold, if not, dust).”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: ‘We chose to take risk’ — how 48 Indians braved harrowing bus ride, hostage fear to escape Sudan