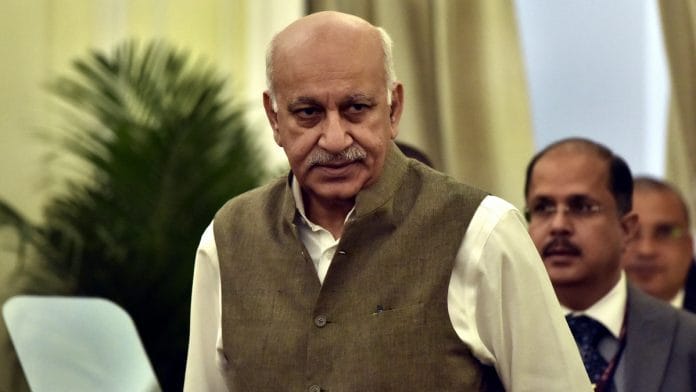

Pallavi Gogoi, a chief editor at National Public Radio in the US, alleges M.J. Akbar raped her when she worked under him at The Asian Age in the 1990s.

New Delhi: A US-based chief editor of National Public Radio (NPR), an American media organisation, has accused veteran journalist and former minister M.J. Akbar of rape, as well as physical assault over multiple years.

Pallavi Gogoi, who shared her account through a column in The Washington Post Friday, is the 21st woman to accuse Akbar of sexual misconduct, but the first to accuse him of rape.

In the write-up, Gogoi has accused Akbar of “defil(ing) me sexually, verbally, emotionally”, across states and continents, when she worked under him at The Asian Age two decades ago.

“I was in shreds — emotionally, physically, mentally,” she added.

Mired in a string of sexual harassment allegations, Akbar resigned as the minister of state for external affairs on 17 October, shortly after returning to the country from an official tour in Africa.

Akbar’s lawyer Sandeep Kapur, a partner at Karanjawala & Co who is leading the defamation proceedings launched against journalist Priya Ramani, the first accuser, said his client “expressly denied” Gogoi’s allegations.

“My client states… [incidents and allegations] are false and expressly denied,” he told The Washington Post.

The day it started

According to Gogoi, the alleged rape took place while she was an opinion editor at The Asian Age in the mid-1990s, when she was 23. Akbar was in his 40s at the time, and served as the editor-in-chief of the national daily, which he also helped found.

In the early days, Gogoi said, she and her mostly female colleagues were “star-struck” by Akbar — a fact he apparently did not let any of them forget.

“He marked our copy with his red-ink-filled Mont Blanc pen, crumpled our printouts and often threw them in the garbage bin, as we shuddered,” she wrote. “There was never a day when he didn’t shout at one of us at the top of his voice.”

However, “mesmerised by his use of language, his turns of phrase”, Gogoi said, she initially accepted the verbal abuse as she thought she “was learning from the best”.

She said Akbar first assaulted her behind the closed doors of his office cubicle in the spring-summer of 1994.

“I went to show him the op-ed page I had created with what I thought were clever headlines,” she wrote. “He applauded my effort and suddenly lunged to kiss me. I reeled. I emerged from the office, red-faced, confused, ashamed, destroyed.”

When she came out, she said, she shared the incident with a friend.

The second incident, Gogoi wrote, took place a few months later, when she was called to Bombay (now Mumbai) to help launch a magazine.

“He called me to his room at the fancy Taj hotel, again to see the layouts,” she wrote, “When he again came close to me to kiss me, I fought him and pushed him away. He scratched my face as I ran away, tears streaming down.”

“That evening,” she added, “I explained the scratches to a friend by telling her I had slipped and fallen at the hotel.”

When they returned to Delhi, Gogoi said, Akbar was “livid” and “threatened to kick me out of the job if I resisted him again”.

Gogoi didn’t quit the paper, she wrote, but adjusted her schedule to ensure she was outside the office as much as possible.

Also read: MJ Akbar says Ramani damaged his ‘stellar reputation’, calls her charges baseless in court

‘Rape and physical abuse’

The alleged rape took place when Gogoi arrived in Rajasthan while covering a caste-based murder.

Akbar was in Jaipur at the time. “The assignment was to end in Jaipur,” Gogoi wrote. When she checked with Akbar, she wrote, he “said I could come discuss the story in his hotel in Jaipur…

“In his hotel room, even though I fought him, he was physically more powerful. He ripped off my clothes and raped me,” Gogoi wrote.

“Instead of reporting him to police, I was filled with shame. I didn’t tell anyone about this then,” she added. “Would anyone have believed me? I blamed myself. Why did I go to the hotel room?”

Months of sexual, verbal, and emotional coercion followed, she added, and she “stopped fighting his advances because I felt so helpless”.

According to her, his grip over her only got tighter after the alleged rape, saying he “would burst into loud rages in the newsroom if he saw me talking to male colleagues my own age. It was frightening”.

Gogoi said she “cannot explain today how and why he had such power over me, why I succumbed”, but “I just know that I hated myself then. And I died a little every day”.

She felt hope, she wrote, when Akbar offered to send her to the United States or the United Kingdom as a reward for her successful reportage of the December 1994 Karnataka assembly elections.

“I thought that finally, the abuse would stop because I would be far away from the Delhi office,” she wrote. “Except the truth was that he was sending me away so I could have no defences and he could prey on me whenever he visited the city where I would be posted.”

Gogoi then moved to the London office, where Akbar would often visit. She recalled how “he worked himself into rage in the London office because he had seen me talk in a friendly manner to a male colleague”.

“After my colleagues left work that evening, he hit me and went on a rampage, throwing things from the desk at me,” she wrote. “A pair of scissors, a paperweight, whatever he could get his hands on. I ran away from the office and hid in Hyde Park for an hour.”

Gogoi said, the next day, she reached out to the colleague she had confided in earlier, and also spoke with her mother and sister, although she “couldn’t bear to share details”.

She decided to use her visa to work as a foreign correspondent in the US to get away from Akbar. On hearing about this, she wrote, Akbar summoned her back to Bombay immediately.

“I left. This time for good,” Gogoi wrote.

She subsequently took a job as a reporting assistant, working the overnight shift at Dow Jones in New York.

“Today, I am a US citizen. I am a wife and mother. I found my love for journalism again,” she wrote, “I picked up my life, piece by piece. My own hard work, perseverance and talent led me from Dow Jones to Business Week, USA Today, the Associated Press and CNN.”

“Today, I’m a leader at National Public Radio. I know that I do not have to succumb to assault to have a job and succeed,” she added.

Also read: MJ Akbar: The brilliant editor who’s now seen as India’s most high-profile sexual predator

Why she’s speaking up now

Addressing the question she knew her allegations would raise — Why now? — Gogoi said she was coming out “because I know what it is like to be victimised by powerful men like Akbar”.

“I am writing this to support the many women who have come out to tell their truth,” she wrote, “I am writing this for my teenage daughter and son. So they know to fight back when anyone victimises them. So they know never to victimise anyone. So they know that 23 years after what happened to me, I have risen from those dark times, refusing to let them define me, and I will continue to move forward.”

Is there something called ‘absolute truth’? And if there is, who adheres to absolute truth…only those who are completely ethical, uncompromising and fearless of the consequences. Yudhishtra, the eldest Pandava was an example of someone who believed in absolute truth. It is plausible that someone is almost instigating US-based, liberal, well-educated, professionally well-entrenched Gogoi to invoke the ‘rape’ word (say ‘Ashwathama is dead’, forget the truth, look at the context). In this sordid drama, sides will be taken, and those supporting Gogoi will simply ignore the statement made by Akbar’s wife. Why did Mallika choose to speak now? Well, not because Akbar is a saint, but perhaps because she knows that Gogoi has crossed the threshold of personal ethics.

Can anyone doubt the truth of this searing indictment … I think the women should bring criminal charges against this predator. He needs to be put away for a long time. This incident also underlines how much a job means to a young, middle class woman, how much abuse she might sometimes be willing to endure to save it. That is what gave Akbar his power, not his silly turn of phrase. After he entered politics, his journalism was gone, in any case.