Police officer Rema Rajeshwari has a local antidote, an education campaign, to fight fake news.

Local musicians are already singing about the evils of fake news when police superintendent Rema Rajeshwari’s convoy rolls up to the dusty village square in one of India’s poorest communities. “Don’t believe these things,” a performer cries out to the crowd.

In a dark blue cap and stiff khaki uniform, Rajeshwari climbs onto a makeshift stage in front of hundreds of villagers. She’s there to try and stop the spread of bogus WhatsApp messages in her district that warn of child kidnappers and roving murderers.

Across India, social media rumors have caused rural villagers to patrol in anxious groups on the look-out for anyone they don’t recognize. These mobs have already killed numerous people. In May and June alone, at least six people died in WhatsApp-related mob attacks in eastern Assam, western Maharashtra and southern Tamil Nadu. There’s also simmering tensions over Hindu vigilante groups who’ve targeted and killed Muslims.

“You see these messages, these photos and videos, but you don’t check if they’re real or fake, you just forward them,” Rajeshwari tells them. “Don’t spread these messages. And when strangers come to your village, don’t take the law into your hands. Don’t kill them.”

With an election due in 2019, some worry a surge of fake, politicized messages could lead to more violence, stoking broader Hindu-Muslim tensions and sparking religious riots. The stakes are already high — Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party is facing declining support, while opposition parties are planning to combine forces to take him on. Rajeshwari said she saw a spike in messages around recent state elections in the neighboring state of Karnataka, and fears more ahead of national polls.

But something surprising is happening here. Rajeshwari’s education campaign seems to be working. There’s been no fake news-related deaths in more than 400 villages under her control in the southern state of Telangana. At a time when governments around the world are grappling with fake news, Rajeshwari’s efforts offer a local antidote to a global phenomenon.

‘Violent Outcomes’

While U.S. President Donald Trump and others use the term “fake news” to discredit negatives stories, false messages are sowing chaos in India’s villages through Facebook Inc.’s WhatsApp messaging service, which has more users in India than any other country.

WhatsApp spokesman Carl Woog said some use the messaging service to spread “harmful misinformation,” but added the company is trying to make that more difficult ahead of India’s next election.

“We’re working to give people more control over group discussions and are constantly evolving our tools to block unwanted automated content,” said Woog, who is based in San Francisco. “In the run up to next year’s elections we will step up our education efforts so that people know about our safety features and how to spot fake news and hoaxes.”

These bogus messages can be particularly dangerous in India, said Michael Kugelman, a senior associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington.

“This is a country where the tendency of nefarious actors to use social media to exploit deeply held societal prejudices increases the likelihood of violent outcomes,” Kugelman said. “The possibility of politicians trying to smear their opponents via WhatsApp rumors could lead to all types of nastiness and raises the specter of political violence.”

In Rajeshwari’s district, gruesome videos and photos spread on cheap smartphones have created mass hysteria, prompting villagers to form stick-wielding patrols to harass strangers.

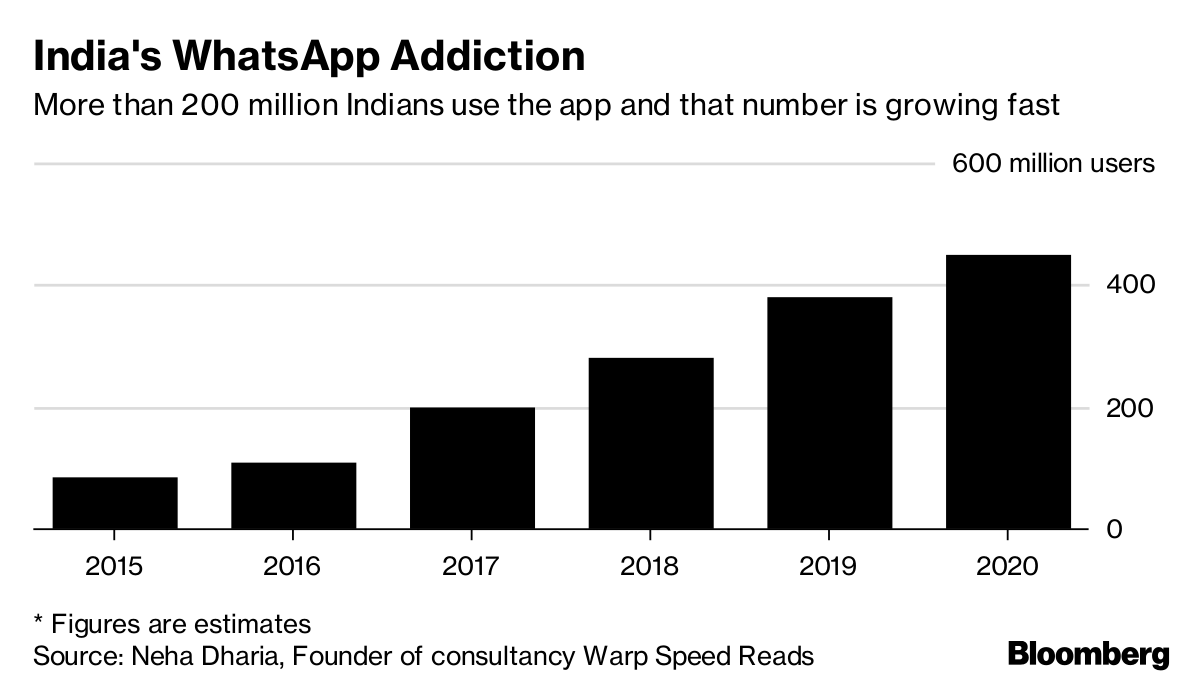

Against these odds, her war against fake news seems impossible to win — more than 200 million Indians use WhatsApp to send 13.7 billion messages each day, according to Neha Dharia, a former Ovum analyst and consultant in Bangalore.

And if any part of India is vulnerable, it’s the 5000 square-kilometers of Rajeshwari’s district in Telangana’s Palamuru region. The local literacy rate hovers around 50 percent, roughly 25 percent below the national average, and the area has a history of political violence.

That’s why Yadaiah Jetti, a 22-year-old shepherd, was terrified when he received a WhatsApp message with a photograph labeling him a child kidnapper who should be killed.

“When I saw it on my mobile, I felt so afraid,” he says.

The message quickly spread across group chats in his village of Manajipet, nestled among the rocky hills of India’s Deccan plateau. But Rajeshwari’s campaign had already penetrated the remote settlement. He approached an officer assigned to liaise with the village and local minor was charged.

“I feel safe here now,” Jetti says as night closes in on his village. “But I still won’t travel.”

Child Kidnappers

In 2009, Rajeshwari joined the Indian Police Service, which is on par with India’s elite foreign and administrative services. She was deployed to Andhra Pradesh and was here when the state split in two to create Telangana in 2014.

Rajeshwari, 39, now lives in a government house that doubles as her office in the town of Gadwal, two-and-a-half hours drive from the capital Hyderabad.

When she arrived in March, Rajeshwari assigned villages to constables who are responsible for visiting at least once a week to speak with locals on social issues like child marriage. On one visit, a policeman found villagers who normally sleep outside in the summer huddling inside, petrified by videos warning of child kidnappers.

Rajeshwari worried WhatsApp rumors had the potential to spark violent riots if Hindus clashed with Muslims. “This region has always been sensitive,” she said. “That’s why we’re so worried about WhatsApp. Any trigger could set it off.”

Rajeshwari ordered training sessions for more than 500 officers. “We had to educate our officers first, before sending them out into the community to educate the people.”

She also spoke to hundreds of village leaders. They deployed drummers to sing about fake news before her team began their work. “We told the villagers – see, look at the people who are in these videos, they don’t even look like Indians,” she said. “Some of the videos are from South America, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Myanmar.”

Local leaders have added her officers into local WhatsApp groups, where the police could monitor messages flowing across the encrypted service.

Cheap Smartphones

The proliferation of cheap smartphones has spread WhatsApp to millions who can’t read, let alone analyze videos. Local SIM card salesmen help villagers install WhatsApp and Facebook, said Dharia, the consultant.

“They are now exposed to much more information from more sources,” Dharia says. “And they take it with the same degree as trust as TV and newspapers.”

In the village of Bagera, Thirumalesh Boya, a 21-year-old construction worker, holds up his battered $44 smartphone to show a bogus message featuring the image of a policeman. “High Alert Please Share As Much As Possible,” it says, before warning of murderous gangs. Boya says he forwarded the message, before learning better from the police.

“We’re not sharing them anymore because we know they’re fake,” he says.

‘Fear In My Heart’

India’s government has been slow to act, though the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting recently released a tender for a company to analyze Indians’ social media posts and detect fake news.

Rajeshwari’s efforts have prompted calls from officers in other states such as Punjab, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu who are hoping to replicate her campaign.

Still, it’s hard to ignore the frightening messages entirely.

“After police said these weren’t real videos, I realized they were fake,” said Mohammed Mahaboob, a 24-year-old shoe salesman. “But still, there is fear in my heart.” –Bloomberg