New Delhi: On what was meant to be Fatima Sheikh’s birth anniversary, scholars were asking an entirely different question: did she exist in the first place?

Widely regarded as among the first female Muslim educators in India, Fatima Sheikh was a lesser-known associate of educational reformers Savitribai Phule and Jyotiba Phule, according to scholars. Modern information available on her suggests that she worked closely with Savitribai, and both women persisted in the face of fierce adversity to enroll children in school and underlined the importance of education.

As a Muslim woman, she would have cut an extraordinary figure in the mid-nineteenth century as a reformist crusader, but precious little else is known about her.

Google dedicated a doodle to her on 9 January 2022, said to be the date of her birth. The Andhra Pradesh government introduced her into textbooks in November 2022. Countless articles have been written about her, celebrating her contributions to education. Reading circles were set up in her name, and a library at Shaheen Bagh protest site was named after her and Savitribai.

And three years after the Google doodle, a feverish debate over her existence propelled Sheikh and the question of her legacy into the spotlight. Scholars combed through their books, every single cited source on Sheikh’s Wikipedia page was excavated, and screenshots of letters and books were forwarded.

The result: A woman named Fatima Sheikh who was friends with Savitribai Phule certainly existed in the mid-nineteenth century.

While few written records about her have been discovered to date, there are references about her littered across history—a mention in a letter from Savitribai to Jyotiba, a registration in a teacher training institute, a negative of a photograph, and a commendation in a British education officer’s report on her and Savitribai’s educational efforts.

She was pulled out of obscurity when the internet discovered her in 2017, when a flurry of articles were published about her online.

“There is historical evidence to suggest that Fatima Sheikh existed. However, there is no evidence to suggest that she was born on the 9th of January,” says Reeta Ramamurthy Gupta, who wrote a 2023 biography of Savitribai, Savitribai Phule: Her Life, Her Relationships, Her Legacy, published by HarperCollins.

“My sense is that Fatima Sheikh is a well known associate of the Phules and a key figure in their work for women’s education. More recently, her work has also been cited as the early investment of Muslims in the Dalit movement,” says professor and activist Susie Tharu, citing Vidyut Bhagwat’s work on women writing on India in Marathi.

The president of the reformist Pune-based society Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal, Dr Shamsuddin Tamboli, tells ThePrint that claiming Fatima Sheikh never existed must be an experiment of some kind. The group’s founder, Hamid Dalwai, tried to highlight her contributions for decades—which the former professor and the head of the chair of Mahatma Jyotirao Phule at Pune University, the late Hari Narke, also acknowledged.

“Of course, she existed, we have records in Marathi books published by the government of Maharashtra that prove it. She may not have written or done anything too notable—her history is not written. But a Muslim woman working in different communities for the sake of education itself is revolutionary, and her contribution is recorded,” says Dr Tamboli. “What is wrong in recognising this?”

Also Read: Savitribai Phule carried an extra saree to school. Brahmins regularly threw ‘filth’ at her

Finding Fatima

Fatima Sheikh would have cut an extremely rare figure during her time.

There are some oral narratives about her, says Marathi scholar and former professor at Hyderabad’s EFL University Maya Pandit. But the other reason why she might have been sidelined by history is because whatever exists about her is in Marathi, and contemporary English sources only recorded the Phules’ association with Muslim men like Gaffar Baig Munshi and Usman Sheikh, widely believed to be Fatima’s brother.

The first, and most convincing, proof of her existence is a reference in a letter Savitribai Phule wrote to her husband, dated 10 October, 1856. “This must be causing a lot of trouble to Fatima. But I am sure she will understand and won’t grumble,” Savitribai wrote.

This letter was first published in 1988 in a Marathi collection of Savitribai’s writings, Savitribai Phule – Samagra Wangmaya, by M.G. Mali. The collection was published by the Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture.

Tharu and Lalitka K. edited a 1991 book, Women Writing in India: 600 B.C. to the present, is one of the first academic works in English that mentions Sheikh as a “colleague” of Savitribai’s.

“The schools Jotiba and Savithribai Phule started in Pune were meant especially for lower-caste girls. Their colleague, Fatima Sheikh, was a Muslim woman. In the letters Savithribai wrote to her brother, which we have reprinted here, we get an inkling, from the many levels at which they were attacked, of the many interests they were undermining,” wrote Tharu and Lalita.

In 2010, British academic Mary Grey wrote about Sheikh training to be a teacher in her book A Cry for Dignity: Religion, Violence and the Struggle of Dalit Women in India. “Savitribai graduated from her Training College with flying colours (along with a Muslim woman Fatima Sheikh), with her husband, she opened five schools in and around Pune in 1848…” wrote Grey.

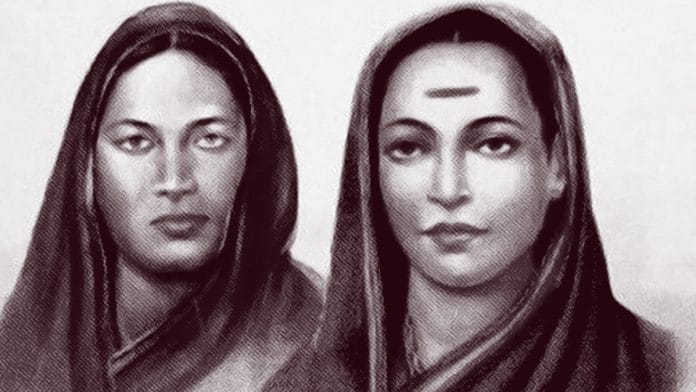

And there seems to be photographic evidence too: Mali’s 1988 book also featured a photograph of Fatima Sheikh and Savitribai.

Noted historian Rosalind O’Hanlon even wrote about this photograph in a 2022 op-ed for The Indian Express. “But Fatima Sheikh remains a much more elusive figure. She did not leave any writings that have survived, and as a Muslim woman, she did not benefit from the energy of generations of Dalit and Bahujan scholars seeking to preserve her memory. Her name is now rightly celebrated, and a brief mention of her life features in Maharashtra’s Urdu school textbook, and in the textbooks of Bal Bharati. But much of the direct evidence of her life has been lost,” O’Hanlon wrote.

Then she explained the photograph. She dated it to the 1850s, and the likelihood of the Phules taking photographs since early images of a young Jyotiba still exist.

Mali, in his book, dated the photograph to an article published in the paper Majur, based out of Pune, somewhere between 1924 and 1930. He wrote about sourcing the photograph from an editor of the paper, D.S. Jogde.

“A rare photograph was printed in the famous book written by a missionary named Lokande. That photograph and the picture printed in Majur look identical. Savitribai’s picture was painted on the basis of the photograph. Eknath Palkar of Pune too had some negatives. Jogde got this negative from Palkar. From that negative, the pictures of Savitribai Phule and Fathima Shaikh became available,” wrote Mali.

The photograph was also carried in the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting’s 1994 publication Krantijyoti Savitribai Phule, a Hindi translation of Mali’s book.

An embellished existence

The controversy over her existence points to another serious problem: the lack of institutional memory, and the ease with which historical narratives can be conjured in the digital age. Marathi, Muslim, and feminist scholars are all in agreement that Sheikh existed. The extent of her contributions—and the modern stories about her—are what’s unclear.

Some of the issues being called into question is whether or not she was born on 9 January, or whether or not she indeed braved stones and dung being flung at her as she went door-to-door with Savitribai, encouraging families to educate their girl children. A lot of this embellishment comes from articles published in 2017 on websites like Velivada, Twocircles, and FeminismIndia. None of them cite any sources.

“There is no evidence to support claims that she was the first woman Muslim educator in India,” Dr Shraddha Kumbhojkar, professor of history at the Savitribai Phule Pune University, tells ThePrint.

“As a historian we also look for motives beyond the fact. There is a tendency to create memories where none exist nor there is a tendency to remember too much. People want to create ideals that are convenient to their present-day politics. If their politics changes, it is no longer convenient for them to have these ideals,” says Kumbhojkar.

In 2022, Narke had questioned the birth anniversary of Fatima Sheikh that many, including Google, recognised as her birthday that year.

“There is a doodle greeting Fatima Shaikh on her birth anniversary followed by an outpouring of congratulations on Facebook. It’s good. But who exactly discovered this date of birth? When was it discovered? On what basis? I would like to understand which document this entry was found. It’s a sincere request,” Narke said in the post.

फातिमा शेख यांना जयंती निमित्त अभिवादन करणारे डुडल आणि त्यानंतर फेबुवर अभिवादनाचा वर्षाव सुरुय. आनंद आहे.

ही जन्मतारीख नेमकी कोणी शोधून काढली? कधी काढली? कशाच्या आधारे? कोणत्या दस्तऐवजात ही नोंद मिळाली हे मला समजून घ्यायला आवडेल..कृपया कुणी सांगू शकेल का? एक कळकळीची विनंती. pic.twitter.com/zUDTQCpoZf

— Prof. Hari Narke (@harinarke) January 9, 2022

In a reply to the same post, Narke also said Fatima’s writings have not been found and there are very few references to her. “Based on these references, people have fabricated stories about her,” he argued.

फातिमा यांचे लेखन सापडलेले नाही.

त्यांचे फार त्रोटक उल्लेख मिळतात, त्याच्यावरून काही लोकांनी मनाने घडवलेल्या कहाण्या रचलेल्या आहेत.

— Prof. Hari Narke (@harinarke) January 11, 2022

Dr Tamboli tells ThePrint there have been plenty of efforts over the last few decades in Maharashtra to erase Sheikh’s role in history.

“Our organisation is a reformist organisation and we do give due credit to those who have worked for such things. Fatimabi is an icon for Muslim women also,” says Tamboli, adding that the group has also honoured women for outstanding contributions in the educational field with an award in the name of Fatima Sheikh.

Many scholars feel that the sudden interest in Sheikh—and the shift in the narrative about her—points to attempts to undermine her perceived legacy.

“I think this is a deliberate plan to malign this tradition that Muslim women were participating in the education process,” says Pandit. Adding, “Individuals don’t matter, but what happens is you’re denying a whole history and the fact that Muslims had aspirations towards the betterment of their lives. This is being deliberately cultivated.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Phule biopic ‘Satyashodhak’ whitewashes Brahmin oppression, plays into political agendas