New Delhi: Enraged by the Gujarat ‘pogrom’ and in search of retribution, an 18-year-old college student’s existential crisis had crystallised in a battle over his beard.

For more than a year, Syed Muhammad Arshiyan Haider had allowed his facial hair to grow, convinced Muslims were unable to confront their oppressors because of their inadequate commitment to the faith. Haider’s parents, alarmed by their son’s growing involvement with neoconservative religion, demanded he visit the local barber.

The young man, though, was more convinced by the argument of a cleric he’d met one evening in 2003: “You should not anger Allah to please people.”

The cleric in question was Abdul Rehman Ali Khan, now being tried on charges of plotting to recruit jihadists, who described his interaction with Haider in his confessional testimony to the police (which under Indian law cannot be used as evidence against him).

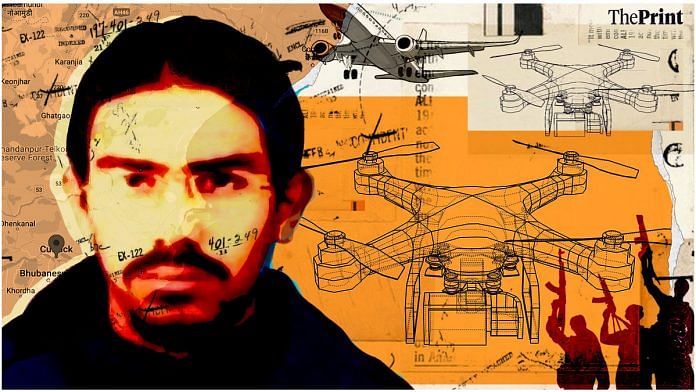

For the young Haider, contact with Rehman was the beginning of an extraordinary journey. The electronic engineering graduate from Aligarh Muslim University, whose family home is in Ranchi, would go on to get a job in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, only to end up using his skills in an Islamic State team that designed suicide drones and short-range missiles that revolutionised the arsenals of terrorist groups.

Since 2017, Haider, now 38, has been imprisoned in Turkey for his involvement in terrorist activities, but not many details have emerged about his life. From classified police and intelligence records, as well as interviews with friends, family member, and police officers, ThePrint has assembled the story of the Indian who helped transform the technology of terrorism.

In many tellings of how Indians ended up in the Islamic State, internet-driven radicalisation plays a big role — but in Arshiyan Haider’s case, at least, the story goes much deeper.

Also Read: At least 40 Indians who joined ISIS now in Middle-East prison camps, find there’s no way home

Cleric with terror links

Abdul Rehman Ali Khan, the cleric who would go on to have a deep impact on Arshiyan Haider, came from unremarkable beginnings in India.

The son of an officer in the Orissa Military Police (now known as the Special Armed Police), whose colleagues remember him as an excellent marathon runner, Khan was educated at a government school in Satabatia village near Cuttack until he completed grade 5. He was then pulled out of school and sent to a seminary to be trained as a cleric.

Khan proved to be an eager pupil and in 1994 gained admission to the famous Darul Uloom seminary in Deoband, Uttar Pradesh. It is here that Khan took a radical turn, according to police records and a contemporary who taught at the seminary.

Ever since the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992, the Deoband campus became known for fierce contests between radical students advocating jihadism, and its conservative teaching establishment. Like many of his contemporaries on the campus —among them to-be al-Qaeda South Asia chief Sana-ul-Haq — Khan was drawn to the jihadists. He fell in with a circle linked to the Jaish-e-Mohammed, an extremist outfit.

Then, in April 2001, an Intelligence Bureau-led operation led to the killing of three Jaish-e-Mohammed terrorists — Liaqat Ali, Abdul Aziz Brohi, and Faizan Ahmad — who were alleged to have been planning an attack on the Hindu temple set up on the demolished Babri Masjid site. Khan, said to have helped provide shelter to Ali, fled Deoband.

For the next two years, Khan tried to make himself invisible, spending time working in mosques across eastern India. Tahir Ali Khan, his brother, was arrested in two terrorism-related cases — eventually securing acquittals in both cases.

Indian jihadists in Saudi Arabia

Sometime in 2003, the cleric had a chance meeting with Arshiyan Haider, but little immediately came of it.

A source familiar with Haider’s family said that at this point, the young man was busy pursuing his engineering degree at Aligarh Muslim University, although he was also active in the Tablighi Jamaat, an orthodox Sunni proselytising movement.

In 2005, Haider travelled to Bangalore (as it then was) and spent several months studying at a seminary, Khan has said, but there’s no evidence that the engineer was involved with jihadism at this time.

Then, in 2008, Haider found a job as a software developer in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, and moved there. It was during his stay in Saudi Arabia that he met his wife, ethnic-Chechen Belgian national Alina Haider, and the couple later had a daughter.

In the meantime, cleric Khan was busy growing his network. According to his testimony, Khan met several times with Bangalore-based doctor Sabeel Ahmad in 2009-2010 and discussed how the struggle of Indian Muslims against oppression might be funded.

When the two met, Sabeel had been deported to India from the UK after serving time in jail for concealing information about a terror plot in which his brother Kafeel Ahmed, an aeronautical engineer, had carried out a suicide attack on Glasgow airport in 2007.

In 2010, when Sabeel Ahmed left India again to work in Saudi Arabia, the cleric put him in touch with Arshiyan Haider.

From 2012 to 2015, Indian intelligence officials say, Haider’s home in Dammam became a hub for pro-jihad Indians. In a series of meetings in Saudi Arabia, held over the next three years, Khan is alleged to have been asked by Haider to recruit Indian nationals for the Lashkar-e-Taiba.

In 2015, investigators claim, Haider paid for Khan to travel to Pakistan through the United Arab Emirates, for a meeting with top Lashkar commanders. Khan was also asked to recruit Indians for al-Qaeda, now led by his old Deoband associate, Sana-ul-Haq.

Late that year, though, Khan was arrested by the Delhi Police, and Sabeel Ahmed placed under detention by authorities in Saudi Arabia, though he would only be deported to India four years later.

The drone designers

Late in 2014, FedEx delivery vans began regularly pulling up outside a nondescript apartment building in the Turkish city of Şanliurfa, famous for the ancient Göbekli Tepe temple, and a mosque marking the site where the Prophet Abraham is said to have been born.

Inside the boxes were remote controls, programme pads, simulator software, antennae, camera pods, micro-turbine engines: Parts to make radio-control toys, but also lethal new weapons for the Islamic State’s arsenal.

Feeling that his network in Saudi Arabia had been compromised, Haider had fled to Turkey with his wife and child in late 2015, setting up home in the country.

An hour’s drive across the border, at the Islamic State caliphate’s headquarters in Raqqa, Syria, Bangladesh-born, Glamorgan-educated computer engineer Siful Haque Sujan had begun assembling the first drones capable of delivering improvised explosive devices. Sujan’s brother, Ataul Haq Sobuj, and business partner, Abdul Samad, used a network of front companies that stretched from Pontypridd, in Wales, to Spain and the United States.

Early versions of Sujan’s drones could only deliver hand-grenades — but Haider’s interventions after he arrived in 2015 increased the lethality and accuracy of the systems. Haider was also working, according to Turkish investigators, on short-range missiles which could attack armour and ships.

Lethal impact, low cost

The idea of using unmanned aerial platforms to deliver lethal ordnance had been around for generations. In the summer of 1849, the Austrian artillery officer Franz von Uchatius had tried to attack forces besieging Vienna using hot air balloons fitted with timed explosive charges. Winds, however, ruined the plan.

Islamic State designers learned how to bring precision to the idea, at a low cost. In 2016, former United States Air Force officer Mark Jacobsen “experimented with building the cheapest ‘insurgent’ drone I possibly could”. “The result required $4 of foam board, packing tape and hot glue, and about $250 in cheap Chinese components. It was ugly, but it could deliver two pounds [1kg] at a range of six to 12 miles”.

In December 2015, a Hellfire missile fired from a United States Predator military drone killed Sujan in a targeted strike in Raqqa. His brother, and several others involved in the attack, were arrested by police in the United States and United Kingdom.

In Turkey, authorities located Haider in 2016, eventually charging him with supplying drones, jammers, and encrypted-communications equipment to the Islamic State. The men arrested with him included Pakistani nationals Nihal Jaweed, a petrochemicals engineer, and accountant Shahid Akhtar. Khalid Taşkandi, another member of the cell, had run a small business in Uzbekistan.

The drones designed by Haider and his team operated upwards of 100 sorties a month as the battle to recapture Mosul raged in 2017, targeting the Syrian Defence Force’s ammunitions supplies and logistics lines. Fifteen or sixteen strikes were not uncommon in a single day.

An authoritative study by scholar Don Rasler has shown terrorist groups can easily continue to procure components from commercial sources worldwide.

Groups like the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed are known to use drones to ferry weapons and explosives across the Line of Control; last year, an Indian Air Force helicopter base was targeted by two drone-delivered bombs, guided by a Global Positioning System. “It’s a matter of time before this technology is used in a terrorist attack in India,” a senior intelligence official told ThePrint.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Jihadi financier, who never gave interview or speech, now uses social media to recruit in India