New Delhi: Every time elections roll around, policymakers and critics raise fears that the government in power will discard fiscal prudence and embrace political populism. In fact, even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) raised this issue last month, albeit for all the countries going into elections this year.

Yet, data from India over the last 20 years shows the central government has been remarkably disciplined about its finances during election time. And it’s not just the data saying so.

Economists, too, point to the Indian government’s historical restraint during election years. They add that more recent reforms — such as the implementation of the Public Financial Management System (PFMS) — have made financial management an easier and more accurate process for the government.

Another advantage is the strong tax revenue growth the government has lately been enjoying, which allows it to spend more without disrupting its fiscal ratios.

“Fiscally, the central government has always been quite responsible over the last two decades,” Ranen Banerjee, leader of the government sector division at PwC India, said. “We have not seen election-related fiscal profligacy or largesse at the central level.”

Also Read: ‘Walked the path of fiscal prudence’ — what economists say about interim budget 2024’s fiscal maths

IMF fears indiscipline

This is in stark contrast to what the IMF has found for the countries it analysed that are heading for elections this year. “The record number of elections being held across the world in 2024 represents a salient risk with regard to fiscal consolidation prospects for the year,” the IMF said in the April 2024 edition of its biannual Fiscal Monitor report.

The report noted that 88 economies or economic areas have already had or are expected to hold nationwide elections in 2024. Together, these represent more than half of the world’s population and 55 percent of global GDP.

“Empirical evidence shows that fiscal policy tends to be looser, and slippages larger, during election years, reflecting a ‘political budget cycle’,” the IMF said.

It added that during election years in these countries, actual deficits end up being 0.4 percentage points of GDP higher than what was budgeted at the start of the year.

That is, for example, if an election-bound country budgeted a fiscal deficit of 4 percent for an election year, the actual fiscal deficit would end up being about 4.4 percent.

Fiscal deficit is simply the amount by which a government’s expenditure exceeds its revenue.

India displays strong discipline

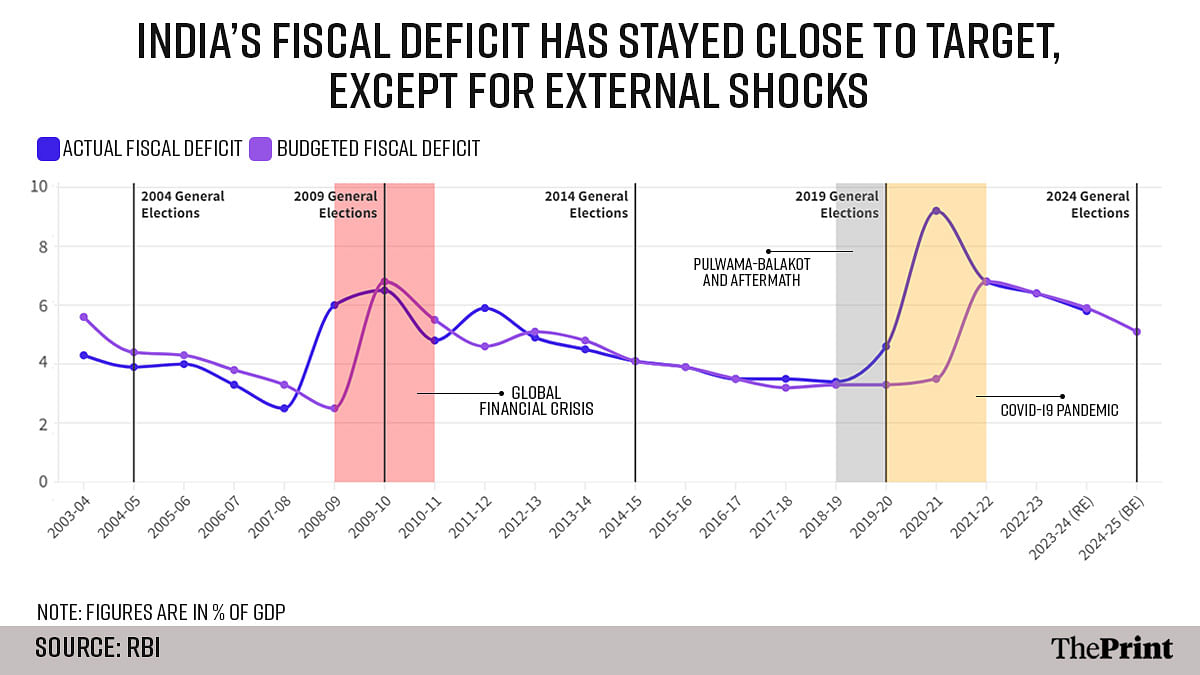

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data on the government’s finances since 2003 shows the IMF’s fears are unfounded when it comes to India. The central government’s fiscal deficit as a percentage of GDP has been on a consistent downward trend, except for spikes caused by external factors.

Notably, over the last 20 years, the fiscal deficit has spiked only in response to external factors, such as the global financial crisis in 2008-09, the Pulwama-Balakot sequence of events in early 2019, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

As soon as the immediate crisis passes, the fiscal deficit again starts trending downwards.

Importantly, elections don’t seem to have any impact on the country’s fiscal deficit.

For election years not impacted by external factors — 2004, 2014, and 2024 — the fiscal deficit has continued its downward trend even in the run-up to elections.

In addition, in all of these cases, the actual fiscal deficit has either met the target set at the beginning of the year, or has come in even lower. This holds true not only for election years but the pre-elections years as well.

This suggests that the central governments in India don’t go in for last minute fiscal profligacy in order to win votes.

“The government has also been fiscally responsible by adhering to its self-imposed limits via the revised Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act while also catering to the larger needs of a fast-developing economy,” economist Rishi Shah explained. “This also has the added advantage of increased investor optimism, globally, as they (the government) have shown that they are largely willing to forego any immediate gains via excess expenditure for longer term macro stability.”

The FRBM Act was passed in 2003 and sets limits on the level of central government debt and fiscal deficit that is permissible. Each Union Budget since has included a ‘Statement of Fiscal Policy under the FRBM Act, 2003’, which presents the government’s medium-term fiscal policy, and its explanations for fiscal slippages, if any.

How government keeps a check

According to Shah, reforms implemented in the last 10 years have further helped with maintaining fiscal discipline.

“This government has shown that the budget is a careful accounting exercise rather than an opportunity to unveil newer policies,” he said. “In fact, policymaking is a year-round process and the budget highlights the broad direction of its larger plans. This, coupled with the discipline brought in because of the Public Financial Management System has meant that spending is being done in a more responsible manner as compared to earlier times.”

The current PFMS started as the Central Plan Scheme Monitoring System of the Planning Commission in 2008-09 as a pilot in four states — Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab and Mizoram — for four flagship central government schemes at the time.

After the success of this initial rollout, the government in 2013 decided to roll out the system across ministries and departments not just in the central government but also the states. Through this, the financial networks of the central, state governments and the agencies of state governments were all linked.

This system has further been enhanced and strengthened since, allowing the government to disburse money to various departments and agencies in a real-time and digital manner.

The other factor that has worked in the government’s favour is the strength of its tax revenue growth. “Revenue buoyancy has been quite strong, so that takes care of any additional expenditure that the government might incur during any year, including election years,” noted Banerjee.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Interim Budget 2024 ditched populism. Modi govt didn’t give in to election temptation