Darjeeling/Jalpaiguri/Siliguri: The frantic calls rained down on a chilly December day. The eighteen year old girl who’d called anti-trafficking expert Amos Tsering said had run away from the house where she’d been confined by a couple whose baby she was carrying. The girl was not formally commissioned by the couple to be a surrogate; nor was there any agreement: She had, simply put, been sold.

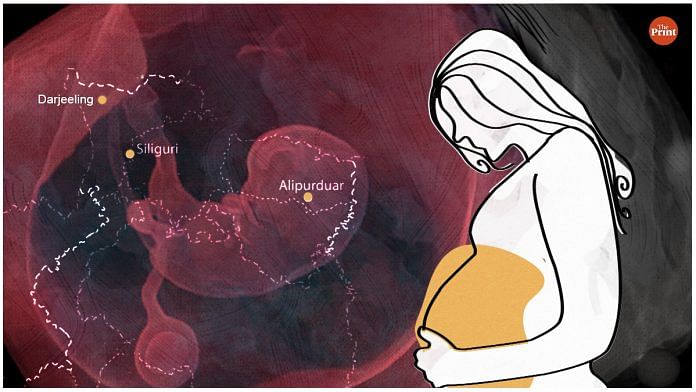

Human traffickers have operated for long in the districts of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar in North Bengal, that share international borders with Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh, with Assam and Bihar nearby. But the business of trafficking young girls has acquired a new focus in recent years. They call it ‘bhade ki kokh’. And it feeds the relentless demand for babies from childless couples across India.

The girl who called Tsering was working in a local beauty parlour, when she met a man who promised her a job with a better salary. Taken to an undisclosed location, she was subjected to artificial insemination a month later. Then, she was handed over to the house of the couple. Six months pregnant, she finally succeeded in escaping.

After being rescued by the local NGO, the 19-year-old is now married and leading a normal life with her baby. The agent and the couple, however, are still absconding.

With The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act 2021 coming into effect from January 25, commercial surrogacy stands banned in India. It allows only ‘altruistic surrogacy’, where no monetary compensation is allowed to be paid to the surrogate mother other than medical expenses and insurance.

But the ground reality is a complex, murky one — where girls are trafficked and laws broken with impunity to meet the immense demand for surrogate children. Veritably, a ‘baby-selling’ industry is thriving in parts of the country.

An area where the scourge is particularly rampant are the interior, and horribly impoverished, villages of North Bengal, especially in the tea garden areas. Minor girls, aged between 16 and 19, from these areas have been trafficked to various places, where they were subjected to ‘traditional surrogacy’ (through artificial insemination, the other method is In Vitro Fertilisation, or IVF), left in lurch after the babies were delivered, or sold again. Sometimes, the minor girls were sexually assaulted, impregnated and their babies sold.

Since there has been little regulation, many shady clinics that have sprouted up for the purpose carried out the surgical procedures on the victims.

Indeed, experts feel that the complete ban on commercial surrogacy may pave the way for more such illegal practices, because the desperate demand for babies from childless couples is not going to abate. Lower income groups who cannot afford to go through the long-drawn process of adoption or altruistic surrogacy, as mandated by the law, would increasingly break it to get babies.

Also read: Is the Surrogacy Bill 2019 unfair to women by limiting their options?

Deceived for ‘bhade ki kokh’

Around November 2020, a 16-year-old girl from a remote village in Jalpaiguri district’s Oodlabari area fell in love with a boy and eloped with him. She was taken to a couple’s house who, she was told, was the boy’s parents.

Months later, she discovered that she was pregnant, and told by the couple that they wanted a “baby girl from her”. As in the previous case, she was confined to a room and subjected to mental torture.

“I was scared, I did not know what was happening. I somehow managed to run away and reached my village,” the survivor, who has a daily wage earner father and an ailing mother, told ThePrint. In due course, she delivered a baby boy at a Jalpaiguri hospital.

“I could not abort my daughter’s child. We are Christians and our Church looks at this as a sin. So I am somehow managing. My daughter is now 17, her son is six months old. We are too scared to go to the police,” her mother said.

A more severe ordeal was suffered in 2019 by a 17-year-old girl from a tea garden in Malbazar area in Jalpaiguri district.

Here, too, the victim was promised a “good job” by an acquaintance, and was told that her mother had agreed on a proposal of her travelling to Delhi for the job of a domestic help.

However, she was first taken to Bihar, and from there to villages in Haryana. She was tortured, and forced to bear a baby through ‘traditional surrogacy’ (artificial insemination).

After the baby was delivered, she was taken to Jharkhand and then to Bihar, where she was then sold into the flesh trade. A group of activists from Siliguri-based anti-trafficking NGOs rescued her from Jharkhand last year.

“I was in the 8th standard when he (the trafficker) took me to Bihar and the other places. My mother works as a tea garden worker, and hardly earns enough to run a family of five. My father is an alcoholic and beats my mother. I have two sisters. He tortures us too. So, I thought of getting a job somewhere else and left,” she told ThePrint, as she sat in the family’s cramped, dingy shack inside the tea garden area.

“I am not able to join school. I am scared that they (traffickers) will come back,” she whispered, breaking down.

Yet, these two victims are the ones who survived to speak of their trauma — there are hundreds who have disappeared without a trace.

In these parts, they have a handy term for the practice for which the girls are trafficked or deceived — ‘Bhade ki kokh’ (womb on rent).

Though there are instances where some young women volunteer to become a surrogate in exchange for a substantial sum of money, surrogacy in these parts are thick with cases in which trafficked girls, mostly minors, were forced into bearing a child through traditional surrogacy, even sexual assault.

And a sense of shame and acute fear of stigma impose a quietus on survivors — no FIRs are recorded with the police.

A border area ideal for traffickers

According to the official records available with the Siliguri Police Commissionerate, the district recorded five cases of trafficking in 2019, seven in 2020 and 10 in 2021.

However, in 2019, the commissionerate recorded 249 kidnappings of minor girls, in 2020 the number went down to 180 and in 2021 it rose to 223. Cases of ‘kidnapping’ include missing complaints too, and there can be various reasons for the girls missing, apart from trafficking.

Darjeeling district recorded one trafficking case in 2019, Alipurduar recorded one each in 2019-21, while Jalpaiguri did not have any trafficking case in the past three years.

The districts of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar share three international borders — with Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. State borders with Assam and Bihar aren’t far away too.

There are 408 tea gardens in the three districts, and their workforce largely comprise Gorkhas, as well as people from the Munda and Oraon tribes. Desperately poor, they primarily depend on labour in the tea gardens and their notoriously meagre wages. A huge number of gardens are sick, many of them remain closed. Tourism is another source of income.

The area is well connected by road and rail — that and the convergence of state and international borders make it easy for traffickers to operate.

“We have also heard of cases in which girls were taken to the Nepal border and then smuggled into Myanmar, but there is no official record for these. We, along with other NGOs, coordinate among ourselves to trace and rescue trafficked girls and help them return to normal life,” Moumita Khati, who runs a transition centre to care for survivors and give them skill training for the NGO Light House Disha in Siliguri, told ThePrint.

Light House Disha is an Anti human trafficking initiative of the Siliguri Community Transformation and Welfare Society.

Trafficking, illegal surrogacy, baby-selling industry

Human trafficking has been a common, though grave, crime in the far flung areas of Bengal, Bihar and Jharkhand for decades. Trafficked girls are generally sold into the flesh trade or into servitude.

However, over the past six to seven years, a new purpose has been added — trafficking girls and using them to produce babies.

“Using trafficked girls for surrogacy is new. We know about them after rescuing some girls. But there are many cases which go unreported and untraced. The poor families do not even lodge missing complaints, fearing backlash in village society. The rescued girls are in trauma and do not want to approach the police. So, the trails go cold,” said Amos Tshering of World Vision India.

ThePrint met a 16-year-old survivor in Light House Disha’s transition centre in Siliguri. She was trafficked to Bihar last year.

The survivor told ThePrint, “I was told that I would be given a job as an ayah. But, they (traffickers) first sold me to a dance bar and then gangraped me. When I became pregnant, they said that they would take my baby and send me to another state.”

She added: “I tried to escape, but got caught. I was beaten up mercilessly and suffered a miscarriage. Three-four months back I was rescued by NGOs with the help of the local police. Now I am taking vocational training at the shelter, I want to get back to school, complete my studies and become an airhostess.”

Khati counsels and trains the survivors to start a new life. “We often hear about survivors delivering babies — some are related to traditional surrogacy, while some traffickers use the girls to produce babies and sell them. They come back to us with trauma, and many of them do not even want to open up.”

Raju Nepali of Duars Express NGO in Jalpaiguri, said, “We locally call it Bhade ki kokh. Traffickers get huge money for this, much more than they get by selling girls for prostitution. They prefer young girls, at times minors, because they do not have medical complications. Often, we have traced the missing girls, but they refused to return.”

Other NGO workers who know the issue intimately also point to a widespread practice of voluntary surrogacy in these districts.

“There are some tea gardens in the area that are closed for 11 years. The young girls go missing from them. Some of them were rescued, some remain untraced, while some return after a year with lakhs of money,” said Nirnay John Chetri of Marg NGO in Darjeeling.

“They do not want to talk about what they did and how they earned such money. The ‘womb on rent’ has been almost an accepted practice in the villages. We know many agree to bear a child for a huge amount of money. But there are cases of forced surrogacy too,” he added.

Debate over banning commercial surrogacy

The Surrogacy (Regulation) Act 2021 that was passed during the winter session of Parliament last year allows surrogacy “when it is only for altruistic surrogacy purposes, when it is not for commercial purposes or for commercialisation of surrogacy or surrogacy procedures, when it is not for producing children for sale, prostitution or any other form of exploitation….”

Talking to ThePrint, Dr Nayana Patel, medical director of Akanksha Hospital and Research Institute, Anand, Gujarat, the decision to prohibit surrogates being compensated needed to be reviewed.

“Why would a woman volunteer to bear somebody else’s child for nine months if there is no incentive or compensation,” Patel asked?

“Being in the field for years, we know how desperate or helpless a couple becomes when they want a child. If this ban continues, then it may encourage illegal practices in an unregulated way.”

Dr Pyali Chatterjee, assistant professor, school of law, Presidency University in Bangalore, also believes the decision to ban paid surrogacy will “lead to more such immoral trafficking,” Chatterjee added.

“The government should draft a legal framework under which surrogates can be registered and go through police verification. The compensation may be directly credited to them. There should not be a middle person between the surrogate and the intended couple,” she argued.

Former union health secretary, Preeti Sudan, disagreed. “The government has done a lot of work before bringing the law. It is a very complicated, complex and sensitive issue. If we commercialised surrogacy, there is no end to it. This will give rise to exploitation of women and illegal or forced surrogacy. Women would be treated as a baby producing machines”.

(Edited by Saikat Niyogi)

Also read: Haryana khaps practiced eugenics, produced world-class athletes: BJP MP says in Rajya Sabha