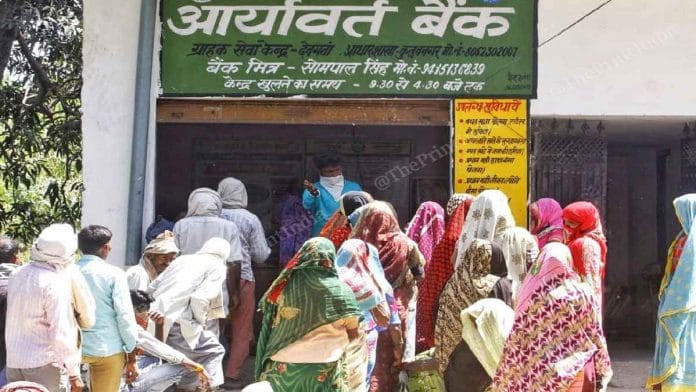

Sitapur: Nearly 150 people, including six women cradling their infants, are queued up outside the local branch of Aryavart Bank at Piswan village in Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh. All of them are waiting for money — be it wages under the rural employment guarantee scheme, MNREGA, welfare aid under the Ujjwala scheme for LPG cylinders, or dues for sold crops such as sugarcane.

Then there is a crowd triggered by the reverse migration — migrant labourers who have returned home from cities in the absence of job and income opportunities during lockdown lining up to withdraw savings to get by this period or crisis.

For many of them, the wait has continued for a week — the days they have spent camping outside the bank from 6 am, through afternoons under the scorching sun, until 5 in the evening. But bank officials claim they are equally helpless.

The rush of withdrawals since the 21-day Covid-19 lockdown kicked in is new for Aryavart, a government-run regional rural bank that serves as the sole bank in Piswan. It often runs out of money and the server frequently malfunctions, the employees say.

While officials at the bank claim they are working ever-longer shifts to cater to the rush, the queue of customers only grows longer. Amid this chaos, social-distancing norms go for a toss and local police officers say they have thrown up their hands trying to convince the villagers to maintain distance.

The wait continues

Netram, 58, is one of the people waiting outside the bank, hoping to withdraw his MNREGA wages. He used to work as a daily wager at the mandi (market) nearby for additional income to provide for his family of six, but it has been closed on account of the lockdown, leaving him running to the bank for his MNREGA wages — the money he claims to been chasing for over four months now.

“I have been running from pillar to post for the last four months to withdraw my MNREGA income, but sometimes the bank says the server is down and other times it claims the money hasn’t been credited.

“My savings and rations got over two days ago with no employment in the village because of the mandi closing down… and other labour work drying up,” he tells ThePrint, waiting outside the bank. “My family has been forced to borrow rations from neighbours, but even they are running short of supplies.”

Prabhu Singh, a sugarcane farmer, says he had to struggle eight days to find a buyer for his produce. “My family and I also cultivate vegetables, but because of the lockdown they are selling for merely Rs 5-7/kg… This is not enough to sustain my family of eight,” he adds.

He tells ThePrint that he did finally manage to find a buyer, but the cash shortage at the bank was holding up his money.

“I finally managed to receive Rs 13,000 by selling my sugarcane to a mill… This money will last for a couple of weeks but the bank is telling me they have no cash,” says Prabhu.

Bank staff ‘helpless’

India’s network of regional rural banks came into being in 1975, with a view to developing “the rural economy by providing, for the purpose of development of agriculture, trade, commerce, industry and other productive activities… credit and other facilities, particularly to small and marginal farmers, agricultural labourers, artisans and small entrepreneurs”.

They are owned in partnership by the central government, the state governments and sponsor banks.

Aryavart Bank is one of the multiple regional rural banks, which together have thousands of branches, and is sponsored by the Bank of India.

Asked about the long queue outside, bank staff in Piswan cited cash shortage, which they blamed on a “30-40 per cent surge” in withdrawals across rural Uttar Pradesh since the lockdown. They say they receive cash supplies every day or two, but they have proved insufficient amid the lockdown.

“Due to the closure of employment opportunities in nearby areas, the villagers have to resort to whatever savings they have in their accounts or the money they receive from central and state government schemes,” says a bank official. “Additionally, the people who have returned from cities are coming in large numbers to banks to see if there’s any money to spare in their home account here.”

“But there’s only a limited amount of cash that is allocated to us, so we can’t do anything about it,” the bank official adds, saying the extra hours of work meant an “intense risk of coronavirus infection”.

Social distancing violated

The crowd of 150 outside Aryavart Bank includes 50 women, six of them holding their newborns.

Manju Devi, 39, cradles her four-month-old daughter as she waits to withdraw the money that has been credited into her account under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, a flagship scheme of the Modi government to ensure gas connections for all households.

Manju says she had been waiting outside the bank since 9 am — sometimes on her feet, seated at other times — but eventually felt compelled to seek the shade of a tree nearby with eight other women sitting by her side.

“The cylinder money is credited by a delay of a couple of months every time,” she says. “We book a cylinder and… on top of that, there is a struggle to to get our own money from these banks.”

She says she had no trouble waiting in the scorching sun, but worried for her daughter.

“That’s why I have to sit here in the shade, at the risk of losing my spot in the queue,” she adds. Manju Devi says she knew about the need for social distancing amid the pandemic but had no option but to sit together under the shade. All the waiting under the sun, she says, leaves them too tired.

Vinod Kumar, a local policeman posted outside the bank with other personnel to manage the queue, says they are struggling to enforce social distancing. “There is already a shortage of cash in the bank and, on top of that, the server fails after every two withdrawals… It is restored only after half an hour, which leads to a crowd outside,” he adds.

“I am tired of instructing these people… I have made repeated requests since morning that they maintain distance from each other but they are not listening now as they are too tired,” he says.

His fellow police personnel are no different, Kumar adds, pointing towards a shop nearby. Tired from managing the crowd all day, the police personnel have found a spot of shade to stand together.