Last weekend, 15 countries signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement.

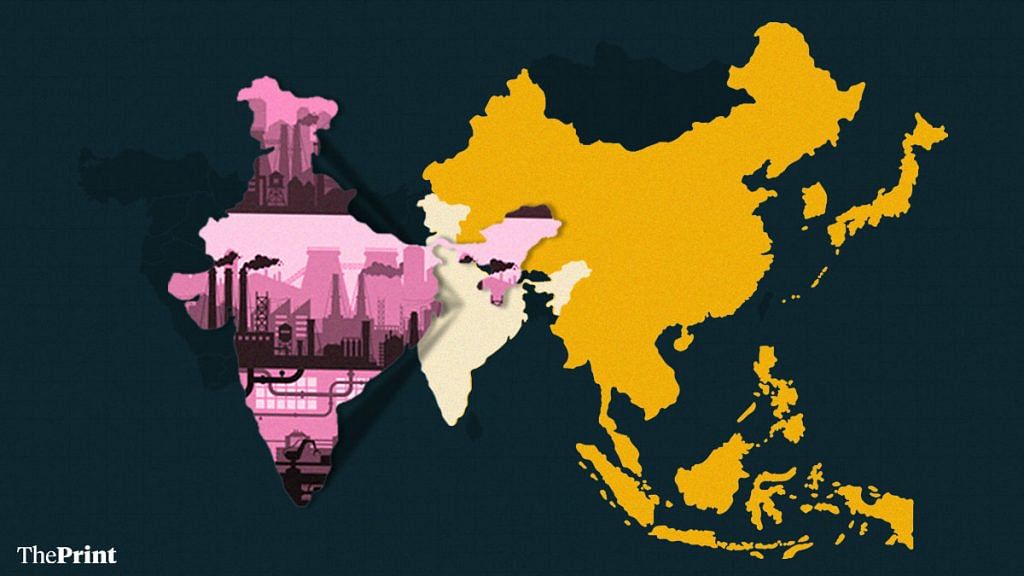

India had withdrawn from the RCEP in November 2019, concerned about the size of its deficits. The tensions with China in Ladakh have also become a factor, though India has been given the option of joining later.

Usually, signing a free trade agreement has required India to cut import duties, since most partner countries already have low import duties. Signing FTAs has only meant giving an advantage to those countries compared to others — it has rarely increased India’s exports.

Signing the RCEP would have meant India losing flexibility to raise tariffs. In this case, India felt it would have been giving China an advantage. The increase in India’s trade deficit with China and the dominance of China in many sectors at a global level have made India wary.

RCEP will reduce tariffs on imported goods in the coming 20 years. It is envisaged that this will strengthen Asian supply chains and boost the member countries’ competitiveness in global markets. Its proponents are of the view that RCEP will help member countries emerge from the economic devastation caused by the pandemic through access to regional supply chains.

Also read: Modi rightly didn’t join RCEP a year ago. SE Asian states are unlikely to benefit much

Concerns about India

There have been concerns that if India wants to be part of global supply chains and become globally competitive, it should not become protectionist. Instead, it should be opening up, including by becoming a member of FTAs like the RCEP.

Textbook trade theory teaches us about the benefits of trade liberalisation, particularly of unilateral cutting of tariffs that make an economy competitive in the long run. However, the entry of China with economies of scale in many sectors, enabling it to expand its exports and destroy domestic manufacturing in many countries in the last two decades, has led to a rise in protectionism across the world.

The RCEP was first proposed in November 2011 to create an integrated market between the ASEAN member countries and their FTA partners. While India was a part of the RCEP’s negotiations, it dropped out in November 2019, citing significant outstanding issues that remain unresolved. India’s concern was that participation in RCEP would expose domestic manufacturers to a flood of cheap imports from China. Indian agriculture, dairy and textile sectors which employ millions of workers were projected to be adversely impacted with the signing of the RCEP. India proposed an auto-trigger mechanism to impose tariffs when imports crossed a certain threshold, but the proposal was not agreed to.

There are concerns that pulling out of RCEP is an act of economic self-harm, as India will stand isolated and continue to under-perform in terms of exports and growth. There are concerns that the decision will hamper India’s bilateral trade with RCEP member countries as they would be inclined to bolster trade within the bloc.

Also read: How will RCEP benefit member nations and what does India’s exit from the trade pact mean

What previous trade agreements have shown

A discussion of the benefits and costs of signing free trade agreements must take into account facts about India’s trade balance and how its industries, exports and imports are placed vis-a-vis the trading partners’. In the case of RCEP, India has a trade deficit with most RCEP countries. While India serves as a huge market for its trading partners, its industries do not stand to gain materially from the trade deal.

India has entered into numerous bilateral and regional trading agreements over the years — it currently has preferential access and FTAs with about 54 countries and Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreements (CECA)/FTAs with around 18 countries.

In an FTA, tariffs on items of bilateral trade are eliminated between the partner countries while they continue to maintain tariffs on non-member countries. CECA is a more integrated package of agreements consisting of trade in goods and services, investments and economic co-operation and intellectual property.

Whether FTAs are welfare-enhancing or not depends on their trade creation and trade diversion effect. Trade is created when a member of an FTA has a comparative advantage in producing an item, and is now able to sell it to its free trade area partners because trade barriers have been removed. Trade is diverted with the formation of an FTA that replaces lower cost imports from a country outside the trading bloc.

The impact of FTAs on India’s trade balance has been ambiguous. A research paper on ASEAN-India FTA finds a reduction in export flows following the implementation of the FTA. A study by the NITI Aayog on the costs and benefits of FTAs for India has laid down certain facts about India’s exports trajectory. The key findings of the study are that India’s exports to FTAs have not outperformed exports to the rest of the world. FTAs have led to greater imports than exports. And most importantly, India’s exports are much more responsive to income changes as opposed to price changes, and hence a cut in tariffs does not boost India’s exports significantly. High logistics costs and supply side constraints make Indian exports less responsive to price cuts.

Also read: Modi govt keen on trade pact with Australia as RCEP takes backseat

RCEP is China-centric

The RCEP is seen to be China-centric, and is expected to elevate its economic and political influence in the region. India has an unfavourable trade deficit with China. While China’s share in India’s imports is roughly 14 per cent, India’s exports to China are a meagre 5 per cent of its exports to the rest of the world. The unfavourable trade balance is further compounded by the composition of exports and imports. While India’s exports to China mainly consist of primary products like ores, minerals and agro-chemicals, imports from China consist of high-value items like capital and manufactured goods like machinery and engineering goods. An FTA has the potential of giving disproportionate gains to China.

India’s exports to China are different from its exports to the rest of the world — 75 per cent of its export basket comprises manufactured goods, of which engineering goods’ share is 24 per cent.

Trade agreements are envisaged to promote bilateral trade, with both parties benefiting as a result of tariff elimination. With China, India’s trade seems to be skewed and may lead to a surge of imports into India.

Reducing the cost of doing business through infrastructure investment and improving the business environment holds the key for improving India’s export prospects. These reforms would ensure that India stands to gain in terms of greater market share from the various regional trade agreements.

Ila Patnaik is an economist and a professor at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Radhika Pandey is a consultant at NIPFP.

Views are personal.

Also read: Modi reviving NAM won’t be enough in post-Covid world. India must reconsider joining RCEP