Rate cuts by the Reserve Bank of India may not find transmission into lower interest rates in the Indian economy if the election promises of large cash transfer programmes are kept. Fears of large government spending without any clear plans to raise tax revenue or cut other expenditure can increase economic fragility as well as create expectations that India will move away from the path of fiscal consolidation. This would mean government can only borrow at higher interest rates. Higher cost of capital would mean lesser private investment.

Election promises of both leading political parties involve larger government spending. Both the BJP and the Congress have made promises regarding cash transfers in their election manifestos. India’s fiscal deficit currently stands at 3.4 per cent of the GDP. Even this is an underestimate, as not all expenditure was shown in this year, and not all borrowing was shown to be explicit borrowing of the central government in the last budget.

Both parties remain quiet on how they plan to fund the additional expenditure — the two paths to not borrowing more are either to tax more or to cut expenditure.

The BJP has already launched the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana for cash transfers to marginal or poor farmers who own land up to two hectares. The manifesto promised to increase the scope of the PM-KISAN scheme to all farmers in the country. In addition, the BJP manifesto promises a pension scheme for all small and marginal farmers in the country. Short-term new agriculture loans up to Rs 1 lakh would be made available at zero per cent interest rate. Even beyond the manifesto, there are promises for collateral free loans of Rs 50 lakh to traders and pensions for shopkeepers.

The Congress has promised farm loan waivers, one crore jobs, MGNREGA days to go up from 100 to 150, and the Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY) to provide Rs 72,000 a year to the 20 per cent poorest families in the country. It has also promised that health expenditure will be doubled to 3 per cent of the GDP, and so on.

If all these election promises are to be kept, central government expenditure would increase by around 3 per cent of the GDP. One proposal is to tax the rich more.

Also read: What Rahul Gandhi missed out when he promised higher GDP expenditure on education, NYAY

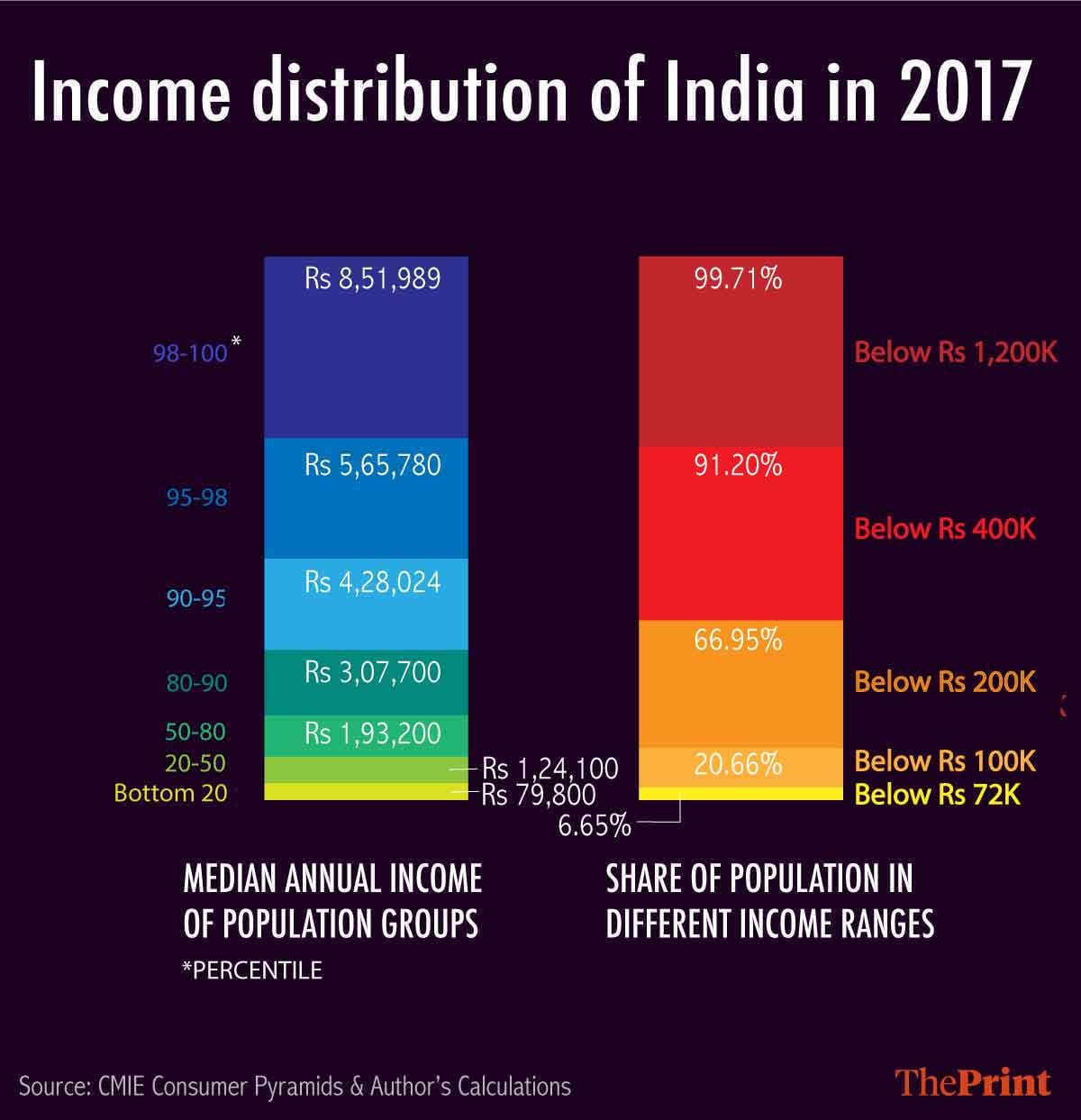

But who is rich in India? The notion of rich is, of course, relative. Households who earn Rs 1 lakh per month in India are rich by Indian standards as only about 0.3 per cent of the population earns more than Rs 12 lakh a year. In India, 99.7 percent of households earn less than Rs 1 lakh per month.

Taxing 0.3 per cent of households to distribute to the remaining looks very hard. So maybe the top 5 per cent should be taxed? But 95 per cent of households earn less than Rs 50,000 per month (or Rs 6 lakh a year).

Eighty per cent of households earn less than Rs 3 lakh a year or Rs 25,000 per month. This is hardly the section that is “rich” and should be taxed to pay for the poor.

At best, raising taxes for redistributing income from rich to poor households would involve taxing about 5 per cent households who earn more than Rs 50,000 per month and transferring it to the poor. This has limited possibilities. Not only is it difficult to tax the middle class politically, even the amount of revenue that can be raised without pushing rates too high and taxing away even 50 per cent of their income, or almost Rs 25,000 per month, away from them will not raise revenues adequately.

Not only is the tax base small, it is also difficult to raise tax rates too much without reducing compliance. In developing countries, wealth tax, or taxing the super-rich, has usually ended up in capital flight without raising revenues.

The other alternative is to cut expenditure. Considering that interest payments, salaries and subsidies are difficult to cut, there are no clear plans outlined by either party on what will be cut. Normally, this means, as it has in the past, that capital spending will be reduced.

In all probability, large cash transfer programmes mean large fiscal deficits, upward pressure on interest rates and moving away from fiscal targets. If all that is promised materialises, India will, unfortunately, almost certainly, head towards a fiscal crisis.

The author is an economist and a professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. Views are personal.

Also read: BJP’s Rs 100 lakh crore infrastructure dream only possible with pvt help, financial reform

We must specify welfare expenditure in relation to the net income of the central government after meeting salary, interest and other mandatory expenses, rather than as a percentage of GDP. This will give a clear picture of the expendable resources. Then rationalization of subsidies can be effectively planned. One can iterate this exercise to check if income can be increased by levying additional taxes, expenses on salaries etc can be reduced and working out level of acceptable level of fiscal deficit as well. To begin with, we must be fully transparent to get the true picture of fiscal deficit. Every one must understand financial position of the country as if it is a family budget. Of course, it is exactly not so but this will be a good starting point to anchor expectations of the people.

The first thing the new economic team will have to do is to come clean on the numbers. What is the fiscal deficit, how much are governments / PSUs borrowing, the rate at which the economy is growing. Let us measure the size of the hole we are in, then work out sensible ways to climb out of it. 2. By a coincidence, last night I saw Walk the Talk with Dr Singh at DSE, from four years ago. Explaining how close India had come to going bust. That can still happen, with much larger sums involved.