It’s been three months since the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus a public health emergency of international concern on its way to becoming a full-blown pandemic.

Despite much hype around several existing drugs, we still haven’t found a proven, evidence-based treatment for Covid-19. The stakes are clearly high, with a vaccine at least a year away, if at all, and countries around the world facing a potential second wave of infections as they start to lift draconian lockdown measures. A conclusive finding that one of the already-available medicines can reduce the viral load or severity of symptoms in infected patients would be a “game changer,” as French state medical adviser Jean-Francois Delfraissy said on local radio on Monday.

For now, we’re still waiting for convincing evidence of whether potentially promising drugs actually work. A European trial of four treatments, dubbed “Discovery,” began in March; it was due to give early results in the first week of April. That date was pushed back to this week after a slow start getting off the ground. In that time, tens of thousands of people have died.

Also read: Remdesivir trial shows Covid-19 patients recover faster, could be first effective drug

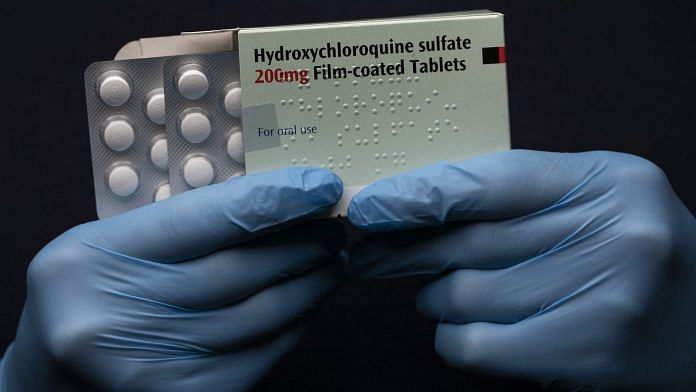

It’s tempting to imagine the blame for lost time lies with bureaucratic red tape and squabbling scientists who prefer idle box-ticking to daring experiments with drugs on the pandemic’s front lines. That’s the narrative favored by supporters of Didier Raoult, the flamboyant French doctor who first flagged anti-malaria drug chloroquine as a promising treatment in February. While the scientific establishment waits for conclusive trial results, self-declared “maverick” Raoult has been using hydroxychloroquine (a less toxic derivative of chloroquine) on patients. U.S. President Donald Trump’s endorsement of the drug, and his pressure on regulators to fast track it, have made it a household name.

But, if anything, it’s the mavericks not the bureaucrats who have slowed things down.

Recent trials of hydroxychloroquine, for example, have been criticized for cutting a lot of corners without showing clinically significant effects. Raoult’s test in Marseilles used a small sample size of 42 patients, their enrollment wasn’t randomized and one patient who died was excluded from the results. Subsequent trials elsewhere were also found to be of limited quality. A review by Birmingham University’s Robin Ferner and Oxford University’s Jeffrey Aronson found that most hadn’t been blinded, meaning those involved knew which treatment was being administered to whom. Other drawbacks included inconsistent treatment procedures, such as the addition of the antibiotic azithromycin, which when combined with hydroxychloroquine can cause dangerous heart problems. Of the 142 hydroxychloroquine trials registered as of April 14, only about 35% were designed to be blinded, the review found.

Sacrificing standards for speed hasn’t just resulted in a lack of evidence; it has hampered and delayed follow-up studies. When the “Discovery” mega-study began enrolling patients in March, it immediately hit a big hurdle — patients swayed by headlines only wanted to be treated with hydroxychloroquine. In the U.S., one patient who was offered the chance to trial Gilead Sciences Inc.’s remdesivir asked for “Trump’s drug” instead. The hype around potential treatments has also spurred countries to hoard drugs, hurting their availability.

Doctors are understandably in an ethical bind in this pandemic. The urge to “try everything” is strong when patients and their families are visibly suffering. Yet speed has to be balanced against other trade-offs like patient safety, too. And the grim truth is that a double-blind, randomized trial of several drugs could have been conducted by now.

This week has brought glimmers of optimism from other trials, though it’s still early days. The Paris region’s hospital association announced that a randomized 129-patient trial of tocilizumab (marketed by Roche Holding AG as Actemra) launched just a month ago has already shown “significant” improvement for Covid-19 sufferers — though the results aren’t yet peer reviewed. On Wednesday, Gilead said positive findings were emerging from a study of remdesivir by the U.S.’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

There are other ways to accelerate research in a pandemic. One option is the use of adaptive platform trials, in which several treatments are monitored at the same time so that resources can be shifted toward those that are the most effective, as my colleague Max Nisen has written. Artificial intelligence can also help. The University of Pittsburgh is using machine learning to power its own adaptive trial of potential Covid-19 treatments across 40 hospitals. Even before testing, researchers are being called upon to use computational methods to screen existing treatments quickly, as in one initiative by a European moon-shot foundation called JEDI.

And if there is conclusive evidence that a cheap generic drug like hydroxychloroquine works, then the pharmaceutical supply chain may find new ways to meet a rise in demand. French firm Rondol Industrie is testing the ability of drug-blending machines to make more efficient doses of hydroxychloroquine that would improve absorption into the human body. The benefits of a lower dose for the same treatment result could include fewer side effects and lower production costs. It would also make it possible to treat more patients with the same quantity of active pharmaceutical ingredient.

Without that evidence, though, we will only be wasting time. Clinical trials are logistically and financially costly, but they’re invaluable. A new pledge by world leaders such as France’s Emmanuel Macron and Germany’s Angela Merkel to raise $8 billion for the development and accessibility of possible treatments for Covid-19 will help. This is a race without an obvious shortcut.

Also read: 2 Indians join global remdesivir trial as the world pins its hopes on it to treat Covid-19

But in India except covid patients other people who are using these tablets are not available even in online also

Sir, the rhetoric essay does not mean anything worthwhile. By the way, who is this Mr. Lionel Lauren? What are his credentials? I looked up in Wikipedia. It pops up only one result. Lionel Lauren is a former French biathlete.

Nowadays we don’t know who writes on what subjects.