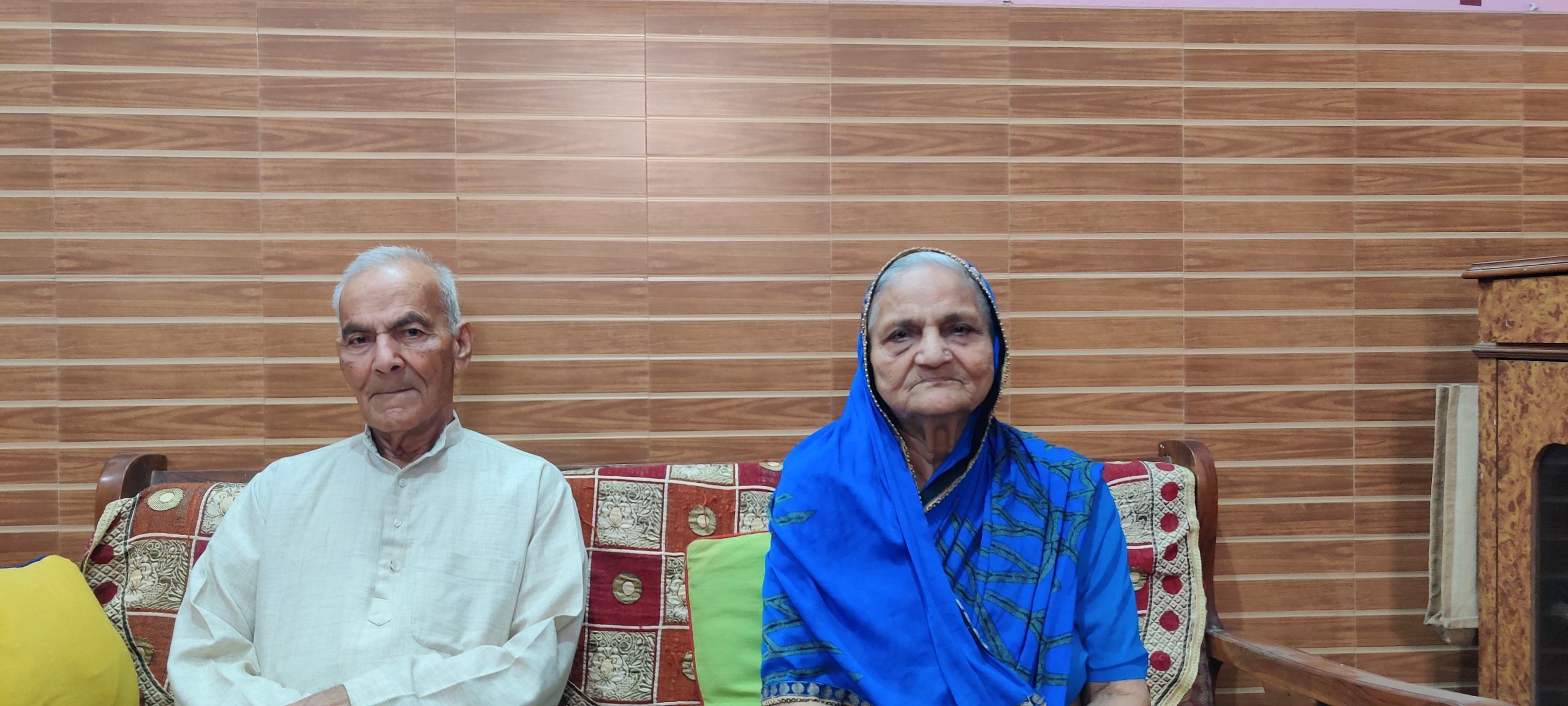

Every morning, retired government officer Subhash Chandra Rai, 86, powers up his boxy computer to answer the 10 good morning messages he receives on WhatsApp from his family and friends. Rai has maintained this steadfast routine for the last two decades with his 79-year-old wife Geeta Rani, though their activities are vastly different.

He draws comfort from keeping his days predictable and structured.

The former director of the Engineering Council of India camps on the veranda of his Vasant Kunj home. In his quiet South Delhi neighbourhood, his face lights up whenever someone he knows crosses his house.

“Namaste! Where are you going?” he shouts out. Or “What are you carrying?” if they have parcels and bags in their hands. Most days, he calls the neighbours’ drivers to sit with him and talk to them about work and politics.

“Our weekdays and weekends all look the same. We don’t even remember how we spent most of our days. We have the same routine where we eat, talk to each other, and spend the whole day at home,” Rai says.

When he has no one to talk to from his veranda, he scrolls through his phone, reading news and checking his social media.

Geeta’s day is busier—household chores after her morning puja, breakfast based on a diet plan given by their doctor, and a trip to the market in the evening to stock up on groceries, fruits, and vegetables. Some days, her husband helps her with dusting and arranging the dining table. With their only child living in France with her husband, Rai and Geeta are each other’s sole companions.

Today, India’s elderly population comprises a little over 10 per cent of the country’s 140 crore population. This number is estimated to increase to 15 per cent (around 22.7 crore) by 2036 and double up to 20.8 per cent (around 34.7 crore) by 2050. Increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility rates are altering demographic equations across the globe, and India is set to face an ageing population bulge at a time when joint family traditions have broken up and there is no institutional care infrastructure either.

Older people in India are traditionally expected to detach themselves from worldly pursuits and immerse themselves in vanaprastha ashram. They attend RWA meetings and bhajans, look after grandchildren, and even go for spiritual retreats. There is always the stereotype of laughter clubs in neighbourhood parks. But with WhatsApp, Facebook, and unlimited streaming content, the source of ‘grey joy’ is changing.

Their days are consumed by screens. A set routine is key. Sending good morning messages, forwarding political videos, watching OTT during the day and ending the night with Vivekananda and Ramana Maharishi inspirational quotes are getting more common among the middle classes.

Dharamwati Gautam, 76, relaxes on a bed alongside her daughter-in-law as she strokes her white and brown cat, Bhura. It’s early evening, nearing tea time. In the adjacent room, her husband, Chhidda Singh Gautam, 81, watches news on a wall-mounted flat-screen TV. “Aditya, make tea for everyone,” he says loudly. Theirs is a busy household. The Gautams share their two-room kitchen house in Shahdara with their daughter-in-law and their grandsons. “My son died during Covid,” says Chhidda, pointing to a photo of a young man on the wall. It’s flanked by two photos on either side–one of BR Ambedkar and the other of Buddha.

“The tea is not sweet,” he rumbles. But his daughter-in-law ignores his repeated requests for sugar. “He has diabetes. We lock all the sweets in the bedroom cupboard.” The pills are on the shelf under the television, so that they won’t be forgotten.

Asia is home to about 58 per cent of the global population of older people.

Despite filial piety forming an integral part of traditional Asian cultures, countries like China, Japan, and Singapore have heavily invested and pioneered models of health and social care for older adults. But in India, elderly people are strangely missing from public policies, debates, and in the poll season from political parties’ election manifestos. Unlike the focus on empowerment of youth and women, the need for geriatric care remains conspicuously absent from mainstream conversations.

The twilight years of the Indian elderly are often spent in withdrawal from public spaces.

“The government can assume that the problem of the elderly is the problem of the families and vice versa. But it’s not a single-handed approach. It’s a many-hands approach,” says Meera Khanna, president of The Guild of Service, a Delhi-based nonprofit organisation that works for geriatric welfare. She wants the Indian government to adopt a “holistic, 360 degree” approach to ageing.

“It can’t be a little tinkering here and there. If we have increased longevity, it’s necessary to upgrade the quality of their lives. What’s the point of a long life that’s terrible?”

Battling changing family patterns

Retired government school headmaster Hasmukh Sagar Sharma greets customers at his son’s grocery store with a wide smile. The brightly lit Masterji’s’s Store in a Najafgarh bylane in West Delhi is a one-stop shop for everything—milk, ketchup, biscuits, dal, detergent, cereals, spices, notepads, and stationery. All his customers are local residents. “How are you masterji?” they ask him while grabbing the bags with groceries and giving him the money.

Hasmukh’s agility, along with his well-trimmed hair, clean-shaven face, and almost wrinkle-free face belies his age. He is 79 years old and has a daily schedule that would put a 20-year-old to shame.

It begins at 5:30 am when he walks through a connecting door from the living room of his house into the store. He has to get the milk supply and attend to the students who buy pens, pencils, and chips on their way to school. The store, which he manages along with his son, is his window to the world outside. People come and go as they discuss politics, exams, and the rising cost of living.

This work has kept him occupied for the last 12 years. Not even a pension of Rs 40,000 could stop him from pursuing his second innings as a storekeeper. When it’s time for his afternoon nap between 1-2 pm, his wife, Dayavati, takes over. Masterji’s store downs its shutters only by 10 pm when everyone in the neighbourhood is back home and their cupboards are stocked. By 11, the Sharmas call it a day.

At 77, Dayavati does all the housework and cooks for the family of five–they live with their son and two grandsons. Running the house is a time-consuming job, but every Monday evening, she visits the neighbourhood Shiv temple, meets fellow devotees, and sings bhajans.

The shop is the axis of the Sharma family. When their son Rajesh lost his job at Maruti Suzuki’s Manesar plant after the violence in 2012, he set up the store adjacent to his house. A connecting door between the shop and the Sharmas’ drawing room allows the elderly couple to briskly navigate their home and their commercial venture.

“We are father and son but we live like friends. It’s all been possible because of my missus. She tells us to keep smiling. My life’s motto is also – be merry,” says Hasmukh.

He compares his son to the epitome of filial devotion, Shravan Kumar – the legendary Ramayana character who carried his elderly parents on pilgrimage in baskets suspended from a pole on his shoulders. Rajesh decided to stay with his parents after his wife left him.

He goes for evening walks twice — one with his father and the second time with his mother, to whom he hands over the daily earnings.

“The health of the older generation is less impacted by disease and more due to loneliness. I make sure my parents help me with the store. That way, they spend time with me and help with my income,” he says.

Studies have shown that India’s senior citizens who live with their spouses and children have high levels of life satisfaction. Many are even open to moving cities to be closer to their working children.

Parul* and Karan* were more than happy to move to Gurugram in 2018 after living in Noida for 25 years. They wanted to be close to their daughter and two granddaughters. With their son living abroad, relocating was the next best option.

“Now, our daughter lives a few minutes away from us. Meeting our grandchildren gives us a burst of energy,” says Parul, who is in her late 70s. She tends to her two indoor gardens, keeps in touch with friends from her old neighbourhoods, and reads. Meanwhile, Karan is busy building a digital photo inventory of the family.

Their most awaited moment is the visit of their two granddaughters, who are 18 and 20. Together, they play board games or watch a movie at the theatre or on OTT.

“Sometimes we go out for lunch. They tell us about their activities. I give them some motivational talk or tell them [about] past events related to their mother,” says Parul, who used to run a distribution business of an American home products company.

In the affluent Gurugram housing colony, which has a significant population of returning NRIs, getting a doctor or ambulance services is a call away, facilitated by the lobby manager. Parul has observed that several families are purchasing two units within the residential compound – one for themselves and the other for their parents.

For the Gangals, whose two sons live in the United States, the CCTV cameras in every room of their Vasant Kanj duplex are a reminder of the fragility of age. But they prefer to celebrate the passage of time. On 5 March, the Gangals marked their 60th wedding anniversary with a havan at the Arya Samaj in Vasant Kunj with a few family members and friends. It wasn’t as lavish as their 50th anniversary that was thrown by their two sons, complete with an exchange of diamond rings.

“This time we didn’t gift each other anything. I think I’m the biggest gift for her as I survive my illness,” jokes VK, who, at 87, is battling a kidney disease. Since his diagnosis last year, the Fortis Hospital at Vasant Kunj has become a big part of his life.

“Last year, we faced our hardest time when he almost stopped breathing and was hospitalised for seven-eight days,” says the wife, Santosh. “Drape your shawl properly,” she tells him. VK gets up from the sofa and goes to his bedroom to bring out the album of their anniversary celebrations.

Three days a week, his driver takes him to Fortis Hospital. It’s a less-than-five-minute drive, but VK prefers to go alone. “I don’t want to trouble my wife. And the doctors, technicians, and staff at the hospital are very caring and nice,” he says. He has a drawer full of medical files that are stacked in chronological order.

Santosh can no longer paint and knit–it strains her eyes; her fingers are losing their grip. But she accepts the ageing process with equanimity.

Indians, irrespective of class, are trying to chart out a course for their ageing parents without a blueprint. India, with its culture of respecting elders and their lived experiences, is changing.

“The breakdown of the traditional system of family, the influence of other cultures, especially the focus on the nuclear family, has changed the attitude of society toward the elderly. Instead of respecting their lived experience, we started devaluing them,” Khanna says.

The shift isn’t limited to urban India. Earlier this month, during a talk on the challenges encountered by elderly women at the India International Centre (IIC), retired IAS officer KN Shrivastava recalled an incident where someone from Uttar Pradesh approached him for help with building an old age home in his village. “Neglect of aged parents is happening not only in urban India but it is also increasing in the villages, which is more hurtful,” he said.

Moreover, the change in societal attitudes is occurring in parallel to a policy vacuum. Khanna contrasted India’s case by citing the example of Singapore where tax benefits are given to young couples who buy homes within a specified distance from their parent’s homes.

“Taxpayers should be given benefits that make it easier to take care of parents. There is the ‘sandwich generation’, which looks after their elderly parents while caring for their kids. They need support to facilitate this dual responsibility,” she says.

Also read:

Company of spouse and internet

Instagram reels have popularised the idyllic retired life by the beach or in the mountains–far from the madding crowd. But the elderly want to be in the thick of things, flexing their age and wisdom.

Harvinder Singh, 75, gets to do just that at the school canteen he runs with his wife, Harjinder Kaur, in Shahdara. Like the Sharmas, the Singhs begin their day at 6.30 am. There are sandwiches to prepare, samosas to fry and pastries to be laid out on the massive canteen counter for hungry students.

“We’ve been doing this for 21 years,” says Harvinder as his wife, 68, oversees the two assistants in charge of preparing the snacks. The canteen is for the Singhs what the grocery store is for the Sharmas – a source of joy, fulfilment, and an outlet to interact with people.

After 45 years of marriage, the husband and wife are experts at reading each other—from the raised eyebrow to the half smile.

“Whenever we argue, we never talk to each other at that moment. We talk after two-three hours, which always solves the problem, and that’s the best key to our happy married long life,” says Harvinder.

Discipline is a religion and keeping busy, a ritual—one that anchors them to the present instead of meandering down the paths of ‘what ifs’ and ‘what thens’. And unlike the sandwich generation hooked to their smartphones and tablets, consuming reels and clips for hours on end, for the Singhs, the phone is a tool to keep in touch with their children, extended family and friends. Theirs is a generation that values real-life interactions.

The Daruwalas may have an 18-year age gap between them, but there’s always something to talk about. Sam Manekshaw’s daughter, Maja Daruwala, a lawyer and human rights activist, is 78 while her husband, Dhun, is 96. They have a rhythm, one that took years to develop.

Maja, currently the chief editor of India Justice Report, said there was a “need for developing balance” in their interests and energy. But their different personalities—Maja with her go-with-the-flow nature and Dhun being the more disciplined one–have caused tensions in the past.

“When we were younger, it used to be an area of conflict with my husband. He was more regulated. There used to be big and little niggles here and there. But we have learned to accommodate each other’s nature,” says Maja.

The generation that waited for the mailman and made ‘trunk’ calls to relatives abroad has embraced technology and the internet.

Subhash Chandra begins his day by responding to good morning messages. Santosh Gangal looks to the internet for her daily doses of spiritual and health tips and good morning quotes in her Arya Samaj, Mahila Samaj and Vedik Prachar WhatsApp groups.

And Maja talks about the “massive accessibility to community and instant communication” via WhatsApp. At her age, she delights in information, entertainment, and companionship that one can enjoy through the internet.

“Previously, we had to wait for tatkal and trunk calls, which took so much time, but now, I can speak to people without having to wait. I speak to my sons and grandchildren, who are distant from Delhi, all the time. I talk to my sister over the phone every day,” she says.

Also read:

Nostalgia and an ‘unshared’ fear

The Daruwalas’ Hauz Khas residence is geriatric-friendly. Their two-storey building, where they live on the top floor, has a lift. They also have two long-time house aides to manage domestic chores. On a spring day, Maja deftly balances work in her study while attending to her husband in another room, who is feeling slightly under the weather.

“Do you want a toast or anything else to eat?” she asks her husband. In a feeble voice, Dhun opts for a toast, and Maja relays the necessary instructions to the helper.

Back in her study, a shelf full of books sits above the study table complete with a big desktop and printer. Family photos of her parents, Sam and Siloo Manekshaw, sister, kids and husband are placed between the wood and glass panels of the shelf.

It’s been Maja and her husband for almost 30 years since their two sons left for college. On some days, they entertain themselves by playing a few games of cards or watching TV together. Occasionally, they visit their friends or attend a lecture at the IIC.

Eight years ago, Maja left the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative she had headed for two decades. “But in my mind, I never retired. My hope is that I can be useful to society and the people close to me until the very end,” she says.

Yet, a lingering concern often occupies her thoughts – her husband’s retired life. Reflecting on Dhun’s extensive career spanning over four decades, during which he ascended from an unpaid apprentice in Air India to a seasoned training flight engineer, Maja acknowledges that “retirement must be a real trial” for such an “active and responsible” individual.

While the ephemerality of life echoes most profoundly among the geriatric community, Maja sheds light on a fear rarely addressed by the elderly – the apprehension of falling ill. The shadow of a frail body lurks ominously behind the allure of boundless time and leisure.

“One aspect that elderly individuals rarely discuss is the dread of illness. They fear the loss of dignity, control over their body and household, and the prospect of dependence on others. No one wishes to burden their family.”

She asserts that both she and her husband have a strong work ethic in the sense that all activities should be anchored in a public purpose. But that “sense of usefulness can get lost” once people grow old and their faculties diminish.

Then there is the weight of nostalgia and the pain of seeing loved ones pass away.

“Longevity can wear one down. You are watching a lot of people you love die. When people are in their 30s or 40s, everything is positive and eternal, but the older you grow, everything gets a little sadder. There are more funerals and hospital visits and you realise your own mortality,” she says.

Back in Vasant Kunj, Geeta Rani and Chandra Rai get ready for their 6 pm ritual. Geeta quickly gets a pot of tea going, while her husband settles on the couch. He’s done talking to the passersby and drivers.

“This indulgence of his sometimes draws unwanted attention,” she says. Occasionally, neighbours and shopkeepers question why her husband seems perennially irritable. She clarifies he’s not always angry but has a loud voice and “likes to talk over people”. Her answer elicits a smile from Chandra Rai.

As the clock strikes 6, she joins her husband in front of their vintage, box-shaped television.

“In the evening, we watch Bengali serials together, have tea and snacks and talk about the shows. Although we spend the whole day together, this time seems to be best for us,” says Chandra with a smile.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)