New Delhi: Two professors at Delhi’s Dr BR Ambedkar University waited for hours outside the registrar’s office for their no-objection certificate to travel abroad. There was a lot riding on it—an interview, an international research project and research funds. By the time they got the certificate, the deadline had lapsed. Another professor, who finally quit the university, did not even bother applying for international conferences for the four years that she taught there.

“The university asked more questions and for more documents than the visa office,” said another faculty member.

The lofty promise and potential of Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD) is in peril today. The campus is in a state of quiet turmoil. Cancelled promotions, campus protests, lawsuits, non-payment of increments, and accusations of caste and gender discrimination have led to an erosion of AUD’s brave new identity, minted 16 years ago – the year it was founded. AUD was interdisciplinary before it was fashionable, its courses were offbeat, and the exchange of progressive ideas was easy. It was meant to be a campus of free, out-of-the-box pedagogy, and an opportunity to fashion a new kind of public university culture in India. Now, professors are fleeing, and students say they have been shortchanged.

Despite having been around for less than two decades, AUD has already lived many lifetimes. It’s thrived, stagnated, declined—from interdisciplinary to insular.

And people are voting with their feet.

“When the new VC took over in 2019, the direction of the university changed. Dramatic changes began in 2020,” said a current assistant professor who is part of the Ambedkar University Delhi Faculty Association (AUDFA). Vice-chancellor Anu Singh Lather didn’t respond to any of the allegations.

There’s been an exodus of faculty members—over 20 faculty members have resigned in the past two years. In this season of discontent, the research atmosphere has also changed, with PhD scholars having to rewrite chapters, and claiming that it’s only a matter of time until the content of their research comes under scrutiny. The university was known for admission exams and interviews rooted in analysis and critical thinking. Now, it’s adopted the standardised test system used across the board.

Faculty members allege that they have been ‘targeted’ for seeking research projects, for wanting to network at international conferences—essentially, for pursuing individual careers. In interviews with ThePrint, several current and former staff members used the word “humiliating” to describe the treatment meted out by the administration. According to the AUDFA, 22 of them have also filed cases against the university, citing non-payment of salaries and discrimination. Among AUD insiders, there’s a widespread belief that the current establishment operates through a ‘coterie’ of deans and administrative officials.

The promise of Ambedkar University Delhi of being the academic avant-garde is in tatters today.

A staff member is currently fighting a case in the Delhi High Court against the university on the grounds that she’s being discriminated against on caste and gender lines. Her supervisor allegedly shouted at her to the point where she could “feel his saliva on her face”. After months of no redressal, she was shifted to another department—without intimation or any explanation.

Despite facing a series of health crises, a non-teaching staff member was transferred to the Mehrauli campus, where she purportedly has no work and is confined to a room filled with noxious paint fumes. She had previously filed a case against the administration, now being contested in the high court.

They know they’ll lose in court. But they want her to quit,” a senior staff member said. They described the difference between the previous and present dispensations as “heaven and hell”.

The promise of Ambedkar University Delhi of being the academic avant-garde is in tatters today.

“There are many tracks of decline—infrastructural, cultural, and intellectual,” said Sayandeb Chowdhury, former assistant professor at AUD’s School of Letters, who left to join Krea University in July 2023. “The faculty was increasingly deemed a group of opportunists who only do things to help their careers, and not the university.”

Also read: Indraprastha University student suicide brings up a storm of anger and a long list of woes

Asking for the bare minimum

An assistant professor who left his job at a leading Delhi University college to join AUD in 2015 said it was the place to be back then. Nine years down the line, he’s keeping his eyes peeled—if an opportunity presents itself, he’ll be the first in line to leave.

The former associate professor who did not apply for international conferences for four years missed publishing deadlines for her book as she didn’t have the mental or physical space in the form of an office. With the onset of the new administration, faculty members are now required to spend 40 hours a week on campus. AUD’s campus—an old heritage building—has long lacked adequate facilities.

Another professor didn’t apply to present their research papers for two years. Basic academic necessities have become uphill battles to the point where the peak doesn’t seem worth summiting. Nor the application worth submitting.

The two professors chasing the elusive no-objection certificate (NOC) were interviewed online and were awarded the project. However, funding is mired in another bureaucratic hurdle—this time between the university and the Directorate of Higher Education.

According to faculty members, this isn’t ordinary bureaucracy or run-of-the-mill inertia. It’s more deliberate. In 2023, in an address to the faculty members, vice chancellor Anu Singh Lather announced that social sciences research at the university was “all cut copy-paste”.

“They have a simple agenda, to prove that those who were there before were corrupt—that those who are in university today, hired by the earlier administration, somehow don’t deserve to be there,” said Sumangla Damodaran, a founding faculty member of the School of Development Studies and the School of Cultural and Creative Expressions (SCCE), two departments key to the firming up of AUD’s reputation as ahead of its time. She resigned in 2022 after 12.5 years at the university.

In response to this stone-walling, there have been three rounds of protests by faculty members: November to December 2022, April to August 2023, and August 2024. Between the protests, they sent petitions to the VC’s office. Last month, the AUDFA, in a letter addressed to the VC, sent a list of grievances.

“They’re [the administration] saying it’s normal attrition when it’s definitely not. This is a permanent government job. For people to leave, it has to be something serious,” said the former associate professor.

She and other faculty members said they were treated with “a primordial suspicion”. In her case, this included being questioned by the proctor for not being in class—when, in fact, she had given her students a 15-minute break during a two-hour lecture, and they were in the canteen.

Being singled out over non-issues and changes in work norms created an atmosphere that was both antagonistic and antithetical to a free university space. She didn’t sign up for this.

“They don’t give permissions, they don’t sanction leave, they don’t release project money. I brought in Rs 2.5 lakh from the Mellon Foundation and they still haven’t reimbursed me for it,” said former faculty.

“I applied in good faith, and I was appointed. But new UGC rules were applied retrospectively, and they (the administration) were recovering money from faculty,” she said. “There was nothing left that could keep me there. There was a boot on our necks the second we stepped out of class.” In its previous life, the university wasn’t bound by the UGC. In 2014, it began to follow its own guidelines, based on the UGC’s Career Advancement Scheme. But once Lather took charge as vice chancellor in 2019, the university switched tack—and began to follow UGC guidelines. This meant that promotions were withdrawn, and in the case of at least 30 non-teaching staff, permanent positions were converted into contractual.

“They don’t give permissions, they don’t sanction leave, they don’t release project money. I brought in quite a large project from The Mellon Foundation through the University of Cape Town and they still haven’t reimbursed Rs. 2.5 lakhs to me out of it,” said Damodaran. “I paid from my pocket. I didn’t want students to not get their payments on time.”

“I am not the sort to constantly go on dharnas and processions. We have work and things to do. I’d spend all my time protesting just to get things, which were the bare minimum,” said former professor.

For mid-career academics like Chowdhury, the firefighting became too much to endure. They couldn’t remain in such a strangulating environment. Chowdhury left journalism to join AUD in 2010. The university’s founders wanted academics from diverse backgrounds, to imbue excitement into the then fledgling institution. Chowdhury, a former journalist, fit right in. One of their experiments with interdisciplinarity was the cross-pollination of academic fields. Damodaran was another example—she taught economics in Development Studies and music as part of the SCCE.

“I am not the sort to constantly go on dharnas and processions. We have work and things to do. I’d spend all my time protesting just to get things, which were the bare minimum. We’re not asking for things out of the basket—leave and a free classroom atmosphere,” said Chowdhury. “When I saw that this had become the culture of the university, I knew it was time for me to leave.”

Exodus to private universities

Attrition is highest in the School of Liberal Studies, School of Human Studies, School of Letters, School of Design, and SCCE, though most departments are bleeding faculty. According to a former member of senior management, “all the schools were created to foster alternative thinking. The intent was not to subscribe to already-made templates”.

The vast majority of faculty members part of this spate of resignations have moved to private universities like Krea University in Andhra Pradesh, Gurugram’s BML Munjal University, and Bits Law School Mumbai. Shyam Menon, AUD’s first vice chancellor who designed the university as a petri dish to see how disparate entities respond and react, is now the VC at BML Munjal.

An academic at Ashoka University, who also did not want to be named, blamed the brain drain first and foremost on the structural problem of underfunding that governs public institutions.

“The problem is with how appointments are taking place in a stifling atmosphere,” he said, insisting that he’s not writing off public universities, yet.

“There are a lot of opportunities being created in private universities. There’s more academic autonomy, money, fewer classes to teach, and a better quality of life. Perhaps those who’ve moved are connected to a more comfortable idea of being a researcher or an academic.”

ThePrint reached out via email to AUD’s vice-chancellor and the registrar and also contacted the university’s PR representative for their response. This story will be updated with their response.

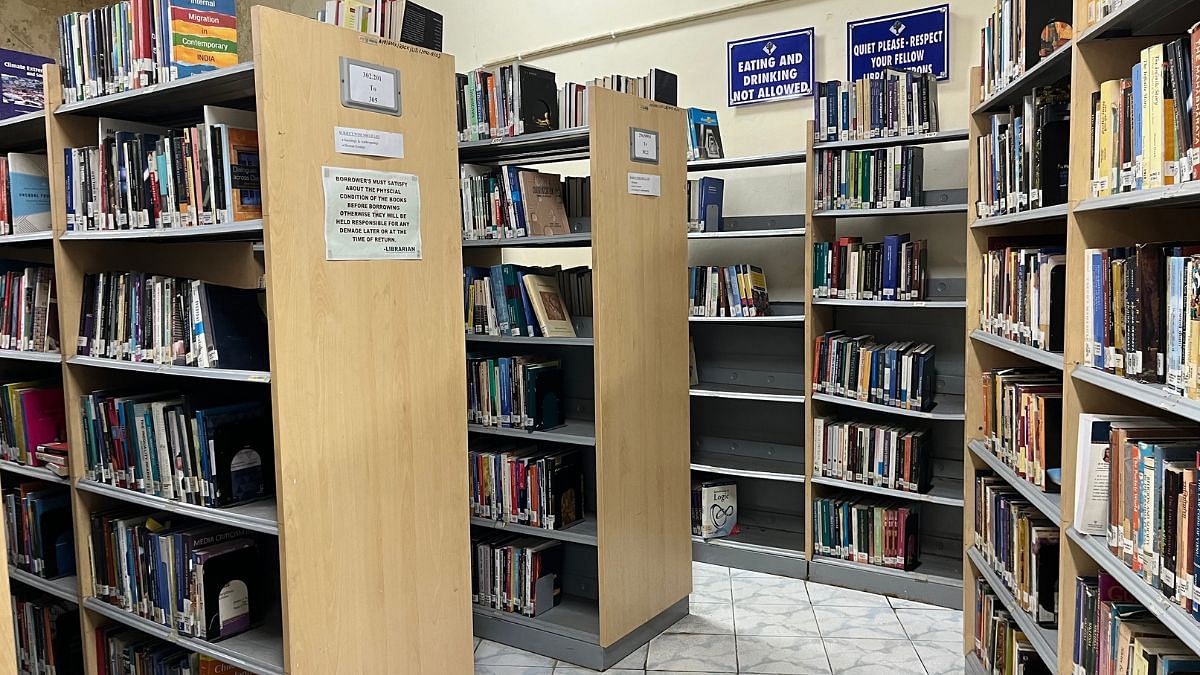

In 2016, AUD was ranked 96 by the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF). Seven years later, its rank dropped to 200. Last year, when ThePrint wrote about the university’s crumbling infrastructure and falling rank, Lather pointed out that AUD was relatively young and working to improve its ranking. They had spent upwards of Rs 15 crore in the last four years for the upkeep of the institution but they could only do so much as the campus was set up in a heritage building, she had said.

Also read: Govt job in Jharkhand means corruption, cheating, exam delays, court cases—JPSC to JSSC

Uncertain students

Students and researchers are hardly insulated from these changes in the air. In fact, they’re equally vulnerable. Many of them joined AUD because of its promise of non-conformist thinking, which they say is coming to a slow but conclusive halt. One student spoke about the disconnect between supervisors and research scholars.

In some cases, their research is directionless. In others, their professors simply aren’t focusing on them the way they used to. Many research students have had to rewrite chapters because their thesis supervisors have resigned, and they’ve had to reorient their research.

“I’ve had to rewrite certain portions of my thesis. One of my batchmates is on her third supervisor. There’s no certainty,” said a PhD scholar who did not want to be named. “We’ve had to start from scratch.”

According to her, what set AUD apart from its counterparts like Delhi University and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) was the individual attention given to students. “AUD brought in that culture of paying attention to students [in the university space],” she explained. “There used to be a fair amount of handholding.”

Now, given the avalanche of challenges within and outside the classroom, this has undergone a rather dramatic change.

“Due to all the structural issues they’re facing, they’re unable to encourage me. I’m not thinking at the scale at which a PhD student is supposed to,” said another scholar currently in their first year. “That rigour is missing. The simple fact is that they’re encumbered with so many other things.”

Despite the hurdles, classes have continued more or less uninterrupted and the flow of teaching has remained. But students pointed to more amorphous shifts—changes in tenor, an undercurrent of anxiety and tension, and the steady retreat of a free-wheeling atmosphere.

Earlier, they’d sit with their professors, and chat for hours over cups of tea. This free trade of conversation is now a rarity.

What’s also impacted their working environment is a rule that came into play in 2022. When it comes to external speakers, only tenured professors can be invited, and prior permission needs to be taken from the administration.

“It’s difficult to say whether research has declined, but the research atmosphere definitely has. The buoyancy needed for research is missing,” said former professor

“Earlier, when we’d know someone [an academic] was coming, we’d rush to invite them because we’d want our students to reap the benefits of interacting with a good academic. But now, whether it’s someone from India or abroad, we have to think twice before inviting them,” said a professor on the condition of anonymity. There’s a fear of administrative backlash, and the possibility that the administration may refuse entirely.

There was a time when KB Athreya, a leading mathematics professor, would simply drop AUD professors a message each time he was passing through Delhi, and would invariably receive an invite. But with prior permissions needed and more bureaucracy, this is no longer the case.

For the first time in its brief history, the university’s flagship lecture event didn’t take place last year, with no explanation given, according to students. One of the scholars quoted above recalled a lecture at AUD given by historian Romila Thapar. She asked her a question on the idea of the zeitgeist informing history.

“Her answer stayed with me. That’s not something I’d ever get from simply reading Romila Thapar,” she said. The eminent historian explained the origins of the word—how it became part of common parlance—while also noting its limitations.

Aruna Roy, founder of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, and Gopal Guru, known for his role in shaping Dalit-centric discourse, have also given lectures at AUD previously. In 2022, the university played host to journalist Sheela Reddy and AAP’s Atishi, who is now Delhi’s newly minted CM, but according to the scholar, the forum was never opened to questions.

There are concrete changes too. The mathematics department did not admit PhD students for an entire year, post-Covid. In the case of the English department, they began admitting PhD students in 2017, and their first batch of researchers is now graduating.

“It’s difficult to say whether research has declined, but the research atmosphere definitely has. The buoyancy needed for research is missing,” said Chowdhury. “It’s not just the quality of research, but engagement with the university. New research has suffered because everyone’s out firefighting.”

Then there is the matter of PhD funds that are not readily available for the scholars.

It’s been five months since the semester began and this year’s entrants to the PhD programme are yet to receive their fellowship money. The administration has told them they will not be receiving the sum for the first two months.

“Classes are still good. I really like the faculty. My interest area matches with their profile—that’s the reason I applied,” said one scholar. “But they need to release the fellowship money. I have to pay rent, there’s travel and wifi which need to be accounted for.” They’ve exhausted their savings.

“It’s a screening committee at the VC level, another oversight committee. They’re trying to create more trouble for students,” the scholar said.

An air of despondency hangs over students and scholars. It’s a far cry from the quintessential liberal arts university, usually associated with lavish, uninhibited academic discussions that stretch on for hours. Over the last few years, security has been beefed up.

Guards lurk every few feet, and most students leave once their classes finish. This is also due to the university’s much-maligned infrastructure. There’s an infestation of monkeys, and spaces— whether to relax or to study—are few and far between.

“I can’t wait to get out of here. The university’s reputation is already so bad,” declared a scholar.

Although their research hasn’t been policed, they say the introduction of URDC (University Research Degree Committee) in 2022 is a move in that direction.

“It’s a screening committee at the VC level, another oversight committee. They’re trying to create more trouble for students,” the scholar said.

Up until 2022, there were three levels of academic scrutiny for PhD students—an academic council, a standard research committee, and a department-level committee. Now, there are four.

“Domain expertise is missing [in the committee]. We don’t know where our work will be sent, or to whom it’ll be sent. They can be from any department,” said the scholar.

Glory days of AUD

Both faculty members and students referred to a golden age of AUD, a honeymoon period of sorts. A time when a new university was being built, and previously unimplemented ideas were seeing the light of day. It was considered so cutting edge that the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and JNU representatives held meetings with AUD’s faculty members to modify their curriculums in accordance with AUD, according to Sumangla Damodaran.

The idea was that courses and departments, which at the time weren’t in vogue in the world of academia, would be given primacy and a platform. Founding VC Shyam Menon, following directives from former Delhi CM Sheila Dikshit, was given free rein. The idea was floated, and then it found its footing on a desk in his study.

“People who were bursting with ideas would be given space to express them and pursue their fruition,” said the former official. The School of Human Studies—which looked at psychosocial thought—was one such idea. Human Ecology was another. While these programmes and courses might be all the rage at institutions today, back in 2007, there was no such focus. It was the same with comparative literature and translation studies, both of which found their place at AUD.

But setting up non-traditional departments and courses is a challenge, more so when the university’s stock itself is dwindling.

Last year, the university began its Masters in Comparative Literature but has found few takers. There are 60 seats and only 20-25 students. The university campus is notorious for its infrastructural challenges, owing to which, there’s no free classroom. Three years since the pandemic came to a slow halt, professors are still conducting one set of classes online.

Certain courses at the university, such as the film studies department’s course in filmmaking, have been scrapped in 2020. Allegedly due to there being not enough takers.

There will always be a certain amount of imbalance, explained the management official, but the demand must be mobilised when there is a social need. For instance, he noted that a management class is likely to attract more students than a philosophy class. However, both are vital to the existence of a robust university space.

Also read: Is Hindi literature adapting to survive? It has more Chetan Bhagats than Omprakash Valmikis

Stripped down to bare bones

“It’s very easy to kill a university,” an education expert

After completing her MPhil at Delhi University and arriving at AUD, a student felt liberated—but also handicapped.

“At AUD, we were exposed to a perspective that was then alien. At DU, we had perfected a ‘copy-paste routine’ and that came under scanner,” she said. “We were exposed to terms that we’d never heard.”

She explained that while she had been exposed to jargon and a theoretical frame, she’d never experienced such academic rigour. The focus was on primary data collection, and a fundamental ground rule—no ‘extractive research’. Research was not supposed to be ‘on people’, but with people. They had to be part of the process.

The university has been stripped down to its bare bones, from which a different body is due to emerge. It’s also the symptom of a larger malaise—part of the tidal wave taking over higher education institutions across the country.

The entrance exams of Delhi University and JNU have always consisted of multiple-choice questions. Meanwhile, at AUD, students were asked to frame essays, which required more analysis and critical thinking. In the English entrance exam paper, up until 2019, while assessing passages—students were asked to deal with tone, images, mood, and style.

Entrance exam papers were crafted completely by faculty members and a 25 per cent weightage was also given to an interview. “Through interviews we could see who was genuinely interested and who was inclined towards the programme. We weren’t going in blind,” said Chowdhury. “We always got good batches. Students thought it’d be more fun to study at AUD.”

Now, at all levels—BA, MA, and PhD—admission is done through the Common University Entrance Test (CUET), a standardised test.

The university has been stripped down to its bare bones, from which a different body is due to emerge. It’s also the symptom of a larger malaise—part of the tidal wave taking over higher education institutions across the country.

“To build a university what you need is a vice chancellor. They don’t need to be academically brilliant. But they need to have a vision and a willingness to implement that vision,” said an education expert retired from DU who did not want to be named. “I don’t see that anymore in India.”

“It’s very easy to kill a university,” he added.

Nearly all academics ThePrint spoke to declared the AUD dead—and lamented its untimely demise. Unlike DU and JNU, it doesn’t have a long and storied history to fall back on, and according to them, this is no blip. But its decline is still the academic talk of the town.

“When I gave in my resignation, no one outside AUD asked me why or what happened,” said Chowdhury. “They already knew.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

This is in reply to Mr. Rajiv Baruah.

Mr. Pramath Raj Sinha graduated from IIT Kanpur in 1986. Also, he holds MS and PhD degrees in Mechanical engineering.

So, it’s you sir who is factually incorrect. Not Mr. Gogoi.

As far as my understanding of the situation at Ashoka University goes, Mr. Dilip Gogoi is largely correct in his assertions.

Thanks for taking the time out to engage on this issue.

I acknowledge that Mr. Bikchandani is not an IITian or an engineer. But Mr. Sinha (Pramath Raj Sinha) is indeed an engineer. He completed B. Tech (Metallurgy) from IIT Kanpur in 1986. Went on to complete a Masters and PhD in Mechanical Engineering from UPenn.

Also, Ashoka’s founders (initially 22 but later grew to 46) aimed to set up an institute of engineering and technology which could match the reputation of leading institutions (such as MIT, Caltech, Georgia Tech, etc.) in the field. Hence, they signed a memorandum of understanding with the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Unfortunately, this is when the Left-liberal cabal got whiff of the matter, managed to catch hold of the founders and convinced them to change their plans. Out of the blue, the focus shifted to the liberal arts. What started out as an attempt to build an Indian version of MIT or Caltech changed into a liberal arts university.

I am not wrong in my assertions. Publicly available data and facts clearly paint this picture. I request you to read up on this issue.

Even Ambedkar cannot save these fools. Investing in social sciences is a waste of precious resources. Instead, the focus must be on basic sciences.

Good riddance. The govt must instead invest in basic science and technology. The future of the nation lies in this.

Social sciences are just for wannabe activists who have hardly anything to do with academics and research. These people are more of a burden for the nation.

An absolutely misleading article. Whether it is dishonest journalism or naivete, I would leave that to the readers. But such yellow journalism is not expected from The Print.

We support The Print for what Shekhar Gupta calls “unhyphenated journalism”. But as another commentator has rightly pointed out, of late, The Print is acting like a PR agent for the disgruntled Left-liberal academics and activists.

This is in reply to Mr. Gogoi. First, factual errors in his message. The public faces of the founders of Ashoka, Mr. Bikchandani and Mr. Sinha are not IITians or engineers. Not that it makes a difference, but I am just pointing out errors of fact. Two, the founders of Ashoka are very worldly, intelligent, successful people of the world. They knew what they wanted, and the builders of Ashoka delivered to their plan. Throwing jargon and labels does not an intelligent intervention make.

Areee andhbhakt aa gaya ek

The Print seems to have been appointed by the Left-liberal cabal to fight on their behalf. There is a clear pattern here. The article by Ms. Apoorva Chitnis on TISS Mumbai followed by this one on AUD by Ms. Antara Baruah.

Seems as if The Print is the PR agency of disgruntled Left-liberal academics and activists.

One can easily understand the context of these articles lamenting the loss of academic freedom in higher education. Every single institution mentioned here – AUD, TISS, JNU, Ashoka – is a Left stronghold. Unfortunately, ever since BJP has assumed power in 2014, promotions, foreign trips (with the excuse of conferences/seminars) have dried up. Funds allocated for social sciences “research” are dwindling.

No wonder they are disgruntled with the “system”.

It’s good that most of them are opting for careers in the private sector – Krea and Ashoka being notable ones. The private sector would surely put them in their place and make them realize their true worth in today’s economy/market.

Also, quite funnily, Ashoka’s founders were duped by this very Left-liberal cabal. The concept was brilliant in that the founders wanted an Indian Harvard or Cambridge which would produce Nobel laureates. So they wanted to focus on the basic sciences and technology and an institution where research was an integral part of life, even at the undergraduate level. Unfortunately, the Left-liberal cabal got a whiff of this brilliant idea and was dismayed to know that the focus was not on Arts and social sciences. Somehow they managed to catch hold of the founding philanthropists and managed to convince them that what is needed in India is investment into the social sciences and Arts. Hence, Ashoka was founded – based on the false belief that social sciences and arts are the pressing needs of this moment. In effect, the Left-liberal cabal managed to create a private institution where salaries are sky high and foreign trips are the way of life. And also where they could host their elite counterparts from the West for “conferences/seminars”. All the while enjoying on the (mostly IITian) founders hard earned money. Money earned through hard work in technology and engineering spent on lavishly spent on social sciences and arts academics and activists – people who just want a good life with no work or responsibilities.

The founders of Ashoka were duped and are now cursing themselves for having fallen into the trap laid out by the self serving Leftists.