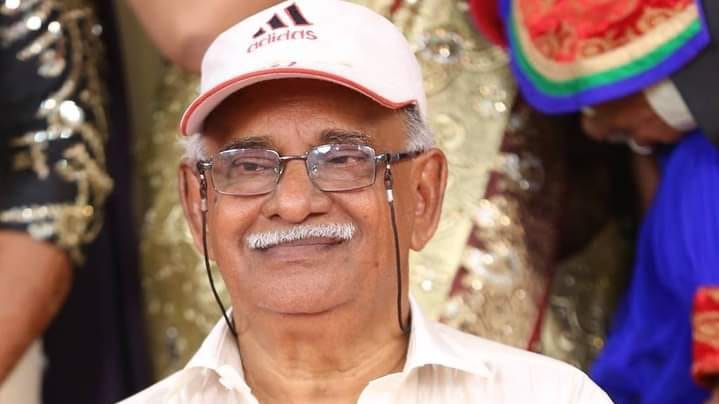

Chennai: Let The Fire Spread. That’s the title of the iconic book that Ku. Thirumavalavan is re-reading in Chennai these days. It’s been six decades since he distributed pamphlets against Hindi language and picketed outside his college campus. He recalls the police lathi charges and self-immolations during Tamil Nadu’s anti-Hindi agitation of the 1960s.

At 80, he says it’s time to rekindle that same Tamil spirit now.

“It did not begin with us, and it is not going to end with us,” said Thirumavalavan, defiant in his culture’s resistance to the language. The book he is reading was written by Tamil Nadu’s former chief minister CN Annadurai. Similar revolutionary Tamil political literature is laid out on the table and bookshelves. He says that now, others will pick up the torch. “Even 60 years after our initial protest, the domination of Hindi has not subsided.”

The three-language formula of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has re-opened old wounds. From Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s MK Stalin to All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s Edappadi K Palaniswami to Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi’s Thol. Thirumavalavan – fiery statements are being issued across party lines almost every day in the state now. Elections are just a year away and Hindi is everybody’s favourite foe. Tamil Nadu’s strident political opposition to Hindi dates to the 1960s, when the Indian government proposed replacing English with Hindi as the sole official language. Though the government backtracked, Tamil Nadu decided to institutionalise a two-language system (Tamil and English). Since then, they have vehemently opposed any central imposition of Hindi.

We don’t flaunt our Tamil identity—it’s in our blood. Even far from home, hearing Tamil makes us turn to find the speaker. That’s our connection – Mathi, son of Ku. Thirumavalavan

The opposition to Hindi imposition isn’t as strong in any other southern states as it is in Tamil Nadu. And yet, a lot has changed since the 1960s. Tamil Nadu’s political economy has transformed as it raced ahead of other states.

Hindi has slowly found its way into Tamil Nadu – not through classrooms, but through everyday interactions and in workplaces. As North Indian migrants move to the state for work, Tamil speakers are increasingly picking up a casual smattering of Hindi, using it to communicate with employees, customers, and colleagues. From doctors and bank staff to yoga instructors, IT industry supervisors and students, many are learning just enough to navigate daily life.

Politicians in Tamil Nadu don’t oppose this organic adoption of Hindi. For them, voluntary learning is a choice, imposition is not. Their resistance stems from a deeper concern: Tamil language is inseparable from identity, culture, and self-determination. The three-language National Education Policy (NEP) route of Hindi imposition is coming on top of a growing rift between Tamil Nadu and New Delhi over GST, delimitation, the looming threat of redrawing of constituencies, and a feared loss of political capital. There is now a resurgence of Tamil exceptionalism in the way the Stalin government has unearthed new archaeological findings about an older Iron Age in the state.

“We have never opposed anyone learning any language,” Palanivel Thiagarajan (PTR), Tamil Nadu’s Minister of Information Technology and Digital Services, told ThePrint. “If they want to learn Hindi, let them. But no one outside Tamil Nadu will dictate how we run our schools.”

An agitating family

A lot has changed in Thirumavalavan’s family since the agitation. His children grew up on a two-language formula diet of Tamil and English. Venmani, his elder son who works in the IT sector in San Francisco, and Mathi, his younger son who manages a hotel business in Chennai, always had the freedom to choose their own languages. But Tamil pride hasn’t diluted. They have never questioned their father’s role in the anti-Hindi uprising.

“When it comes to Tamil and Tamil culture, it’s natural for anyone in Tamil Nadu to take pride in the language and its unique identity,” said Mathi, adding that his father never imposed any beliefs on them. “We don’t hate any language. I learned French in high school to boost my Class 12 board exam scores, but I haven’t used it since.”

If they want to learn Hindi, let them. But no one outside Tamil Nadu will dictate how we run our schools – Palanivel Thiagarajan (PTR), Tamil Nadu Minister

Both sons studied at English medium schools, with Tamil as a language subject. Thirumavalavan’s granddaughter, studying ICSE (Indian Certificate of Secondary Education) curriculum, was offered multiple language options – including Hindi – but chose French instead.

“My younger son, during his college days in a Telugu minority institution, picked up Telugu fluently in three weeks just by interacting with friends. That’s how language learning should happen – naturally, without coercion,” said Thirumavalavan.

Mathi added that he would be open to learning Hindi if it became necessary for his business or daily life. He recalled how a cousin, who has lived in Japan for over 15 years, learned Japanese within his first two months there, out of sheer necessity.

Their family’s two-floor villa in Chennai is replete with Dravidian and Left-wing literature. The walls are spotless, but the tables are stacked high with books that the crowded shelves cannot accommodate. Among them are old, yellowing editions of Theekathir, a Communist Party of India (CPI-M) newspaper, and Dravidian history books such as Manila Suyatchi by Murasoli Maaran.

Memories of Thirumavalavan’s college days linger in this trove—when he passionately participated in student-led resistance movements against Hindi.

“We planned to march from our college and block the railway station,” recalled Thirumavalavan, who was a student at Annamalai University, Chidambaram, at the time. “The police tried to stop us, shooting one of the protesters in the shoulder. But we continued to march.”

As a young English literature student in 1963, he started printing pamphlets when he first heard about the Centre’s plans. Initially, there were only five of them—fellow students from the English department, and some Tamil language enthusiasts.

“Despite being from the English department, I reached out to students across the university and even affiliated colleges. The response was overwhelming,” he said, adding that his plan was to not rest until Tamil Nadu’s linguistic freedom was secured.

Thirumavalavan worked as an English professor at a government college in Chennai before retiring in 2005.

He is a follower of Tamil social reformer EV Ramasamy Periyar, who protested against the Congress-led Madras Presidency government’s decision to introduce compulsory Hindi education in schools in 1938.

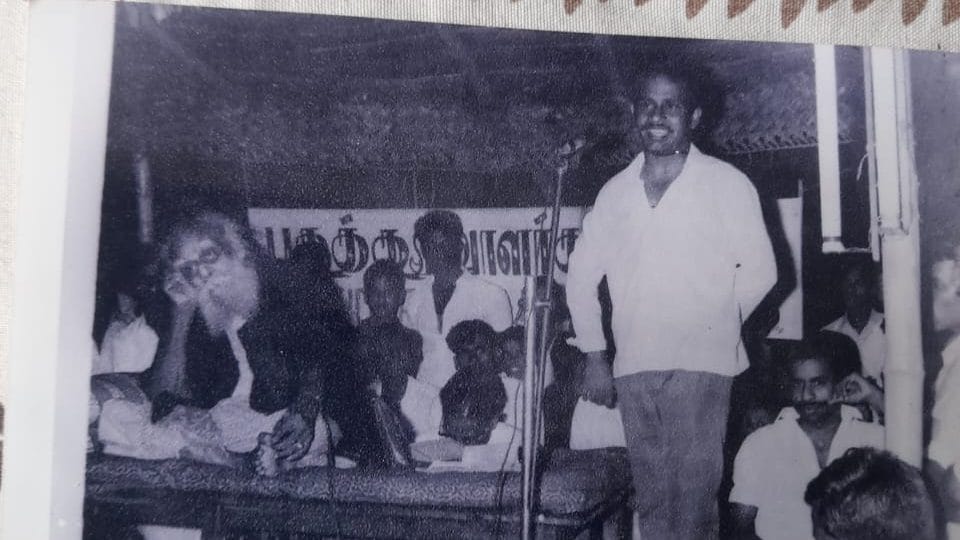

Thirumavalavan holds on to many newspaper clippings from his college days. But he especially treasures one – featuring a photo of him speaking at an event honouring Periyar. “I joined the Anti-Hindi protests but never the DMK,” he said. “I follow Periyar’s ideas. Speaking before him at an event I organised is a memory I cherish from the struggle.”

As he spoke, his son Mathi rushed downstairs. Ready to head to work, he teasingly said: “He loves Tamil, yet he’s an English professor.”

Thirumavalavan smiled as Mathi lingered for a brief conversation, explaining what Tamil meant to his family. “We don’t flaunt our Tamil identity—it’s in our blood. Even far from home, hearing Tamil makes us turn to find the speaker. That’s our connection.”

Mathi doesn’t regret not learning Hindi. “I could learn it anytime with a simple class. But understanding our culture takes deep study, so I chose Tamil. Other languages are just for getting by.” His young daughter, now in Class 1, has picked up French like her father. “It was her choice. We can teach basic French at home, but Hindi would be extra pressure. We let her decide,” he said, before finally leaving for work.

Also read:

New agitations

Students and activists in Tamil Nadu hardly protest on the streets anymore. The anti-Hindi resistance has largely moved online, unfolding through viral memes, social media posts, stand-up comedy, and reels.

Politically active youth, organised under DMK’s parent organisation Dravidar Kazhagam as well as other Dravidian groups, use X to push back against Hindi.

The DMK and AIADMK are working to bring together these unorganised young people, using their love for Tamil to further their political objectives.

In the past, those who spoke in pure Tamil were seen as the best orators, but nowadays, young people use colloquial Tamil and still capture the audience’s attention. We don’t insist on pure Tamil; the goal is to connect with the masses through these politically engaged young people – A Arulmozhi, Dravidar Kazhagam’s propaganda secretary

The DMK, for one, held oratorical competitions called ‘En Uyirinum Melana (More than my life)’, a phrase former Chief Minister M Karunanidhi commonly used while referring to his party members. Through this contest, held in different parts of Tamil Nadu from October 2024 to February 2025, they discovered as many as 100 young people who speak Tamil fluently and would greatly help promote the party’s ideology.

There is no benefit to forcing our students to learn three languages compulsorily. Why should we adopt a failed model? – Palanivel Thiagarajan (PTR), Tamil Nadu Minister

Following in DMK’s footsteps, the Opposition AIADMK’s student wing is also planning its own speaking competition to find talented Tamil speakers for their party.

Dravidar Kazhagam’s propaganda secretary, A Arulmozhi, who was also one of the judges at DMK’s oratorical competition, said that the way young people use Tamil has changed a lot over time.

“In the past, those who spoke in pure Tamil were seen as the best orators, but nowadays, young people use colloquial Tamil and still capture the audience’s attention. We don’t insist on pure Tamil; the goal is to connect with the masses through these politically engaged young people,” she explained.

Also read:

Politics and culture

Tamil Nadu’s resistance to Hindi isn’t just about language – it’s about identity, autonomy, and political assertion. Its provenance goes beyond the 1960s, when the British-era Madras Presidency government, led by the Indian National Congress’ C. Rajagopalachari, attempted to make Hindi a compulsory subject in schools.

“In the 1930s, the resistance was about identity,” said PTR. He explained that at the time, Hindi was seen as a tool of Delhi’s administrative convenience, imposed from the top down. “The question Tamilians asked was, ‘Who are you to subjugate me?’”

The fight only intensified in 1965, when the Congress-led central government attempted to replace English with Hindi as India’s official language. What followed was one of the most significant language protests in Independent India’s history.

What is the point of burdening a child with a language, in an environment where it will be impossible for them to practice it. Hindi is not opening any opportunities. I reject that idea – Karti Chidambaram, Congress MP

Successive Dravidian governments – both DMK and AIADMK – have upheld the two-language system of Tamil and English, ensuring that Hindi remains optional and never mandatory.

“Today, we reject the NEP’s three-language formula based on hard evidence,” PTR said. He pointed out that in North India, students even struggle with their second language (English) – let alone a third. Tamil Nadu, on the other hand, has flourished with its two-language system, producing a globally competitive workforce. “There is no benefit to forcing our students to learn three languages compulsorily. Why should we adopt a failed model?”

PTR emphasised that international curricula – including the Switzerland-based IB (International Baccalaureate) and the United Kingdom’s IGCSE (International General Certificate of Secondary Education) – also follow a two-language structure. This proves, according to him, that Tamil Nadu’s approach is not an anomaly but an effective, globally validated model. He argued that the success of Tamil students in high-skilled fields like medicine, law, engineering, and governance is evidence of the system’s merit.

At his office in New Delhi, Congress member and MP Karti Chidambaram echoed PTR’s thoughts, highlighting that resistance cuts across party lines.

“There is no study in the world which says you need to study three languages,” said Chidambaram, adding that the idea of a third language is in line with Bharatiya Janata Party’s plan to create a uniform state. “What is the point of burdening a child with a language, in an environment where it will be impossible for them to practice it. Hindi is not opening any opportunities. I reject that idea.”

He sees another sinister fallout of this imposition – slow cultural erosion.

“What I fear is, the central government under the BJP will send us Hindi teachers if we were to implement NEP,” said Chidambaram. “They will say, since you are not filling up the teachers, we will send them to you since we are partly funding the scheme.”

According to Chidambaram, the BJP is vying to create an India without linguistic differences or regional identities – just one large, administrative bloc that it could easily govern. But for Tamils, linguistic identity is important. And just because they accept this identity, doesn’t mean they don’t accept the Union of India.

At the state level, AIADMK – the main Opposition party in Tamil Nadu – expressed that it would always stick to the two-language formula of former CM Annadurai, who enforced the policy in 1968.

“In fact, when the draft NEP 2020 was released, AIADMK was in power in the state and we wrote to the Union government then stating that we would like to follow the two-language formula,” said AIADMK students’ wing secretary Singai G Ramachandran. “By that time, we were also in alliance with the BJP. Despite being in alliance, we showed our resistance to the three-language formula.”

Also read:

Film industry response

The Tamil film industry has long been the stage for enacting Dravidian ideals and has often included scenes and dialogues that mock Hindi and Hindi-speakers. The sentiment against Hindi imposition is so deep that it has been part of popular culture. Key figures like Annadurai and Karunanidhi have used cinema to instill Tamil pride in the masses.

In the 1980s, Hindi was often portrayed in a humorous light, reflecting Tamil people’s reluctance to adopt the language. The 1981 film Indru Poi Naalai Vaa, directed by K Bhagyaraj, features a comic scene where a Tamil-speaking character struggles to speak a Hindu dialogue – “Ek Gaon Mein Ek Kisan Rehta Tha (A farmer used to live in a village)” – inadvertently turning it into humorous gibberish.

Similarly, in the 2009 Tamil movie Abhiyum Naanum, directed by Radha Mohan, Hindi was subtly mocked through light-hearted humour – through a father-daughter relationship and a Punjabi character’s arrival.

We actually enjoy all sorts of Hindi movies and sometimes draw ideas from them. When making a pan-India film that includes Hindi, we tweak scenes (like a fight sequence) to appeal to North Indian viewers. We do not reject Hindi, but we show it in a way that fits the story, and not as some ‘national language.’ This comes from more politically conscious directors entering the field – K Prakash, assistant director in Tamil films

The film stars Prakash Raj as the father, Trisha as the daughter, and Ganesh Venkatraman as the daughter’s Punjabi Sikh boyfriend. Raj is visibly uneasy upon meeting the Hindi speaking North Indian, struggling to accept him as her daughter’s partner. He often interrupts the couple with dialogues like “Hindi nahi maalum (We don’t know Hindi)”, and mispronounces Hindi words. These scenes resonated with audiences in Tamil Nadu, who often enjoy playful jabs at Hindi.

However, after the 2000s, Tamil cinema took a more critical stance on Hindi imposition, often portraying Hindi-speaking characters as outsiders or antagonists. In Kaala (2018), directed by Pa. Ranjith and starting Tamil super star Rajinikanth, Bollywood actor Nana Patekar plays a Hindi-speaking North Indian politician, symbolising external control over Tamil identity.

Despite this resistance to Hindi, Tamil directors have found success in Bollywood. Arun Kumar (Atlee), who directed the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer Jawan (2023), is a prime example. Ironically, K Bhagyaraj – who once poked fun at Hindi in his films – directed the 1986 Hindi movie Aakhree Raasta starring Amitabh Bachchan.

K Prakash, an assistant director who has worked on Rajinikanth films and is now writing a script for his own project, said that the Tamil film industry doesn’t look down on Hindi films or the Hindi language.

“We actually enjoy all sorts of Hindi movies and sometimes draw ideas from them. When making a pan-India film that includes Hindi, we tweak scenes (like a fight sequence) to appeal to North Indian viewers. We do not reject Hindi, but we show it in a way that fits the story, and not as some ‘national language.’ This comes from more politically conscious directors entering the field,” he explained.

Now that the state’s movie industry has become more accepting, Tamil YouTube comedy channels are making satirical shows about North Indians and Hindi.

Parithabangal, a popular YouTube channel run by comedians Gopi and Sudhakar, often portrays North Indians and Hindi through stereotypical skits focusing on cultural and linguistic differences. Their recent video “North Train Paavangal” depicted North Indian migrant workers in Tamil Nadu as unhygienic and loud. They were shown chewing paan in a train, and playing loud music without earphones. In the video, they mocked how Hindi speaking people from the North often expect Tamilians to understand their language.

It drew some criticism, too.

“Although I love Parithabangal for their consistent quality and capturing every aspect of Tamil life, I can never endorse their content on North Indians. It’s always classist and racist to the core,” said Mathur Sathya, a CPI activist. Their imitations may be accurate but the videos blame North Indian people for their own plight instead of pointing at the system that keeps them in perpetual deprivation.”

A couple of years ago, there was a viral T-shirt trend in Tamil Nadu which said: “Hindi theriyathu, poda (I don’t know Hindi, go away)” when the NEP row came up. Now, in the last week, a new meme took off on the T-shirt joke.

Vadivelu: “It’s only a strategy to sell t-shirts (Hindi theriyathu poda t-shirts)”

Parthiban: “Oh, then you print ‘I love Modi’ on t-shirts, sell them, and show me!”

Also read:

Migrant workers

A lot has changed in Tamil Nadu since the early 1960s, though. For one, there are more North Indian workers across the spectrum – from IT engineers to construction labourers, hosiery tailors, and hospitality workers. As Tamil Nadu prospered and its status as a job-generator state rose over the last 30 years, it attracted scores of Hindi-speakers. Market forces have brought about more Hindi in the Tamil Nadu air.

Their presence in Tamil Nadu has complicated the language politics a bit as well. The sentiment against Hindi imposition is still high but barriers are slowly breaking down. The influx of migrant labourers is increasingly becoming an economic necessity for businesses, diluting cultural angularities of the previous century.

As a Hindi speaker, I have to be careful here – Pradeep Kumar, a waiter in Chennai

Pradeep Kumar, a 23-year-old from Bihar who works at a tea shop in Chennai’s Anna Nagar, moves swiftly between taking orders, clearing tables, and serving steaming cups of tea. His mother tongue is Hindi, but in the last six years, Kumar has picked up enough Tamil to converse with customers. He has learned phrases in Tamil – ‘What do you want’, ‘Did you pay for it’, and ‘Has the money been transferred?’. Quick sentences to help him on the job.

“As a Hindi speaker, I have to be careful here,” said Kumar, looking over his shoulder to check if anyone was eavesdropping. Both he and his brother both work at the tea shop. “One day, when going up a building for a delivery, I had an argument with a lift operator when he realised I wasn’t from here. Nothing happened, but I feel I need to be on guard.”

Kumar said that while he has had no physical altercations with anyone, there have been microaggressions. Some people speak to him rudely upon learning of his background. They mock him about the lack of jobs and dilapidated conditions in Bihar. Sometimes, even customers make him feel like he is infringing on their territory. It’s often hard to understand if this antipathy extends to just Hindi or all outsiders.

His first job in Tamil Nadu was in Erode, where he mainly did cleaning work at restaurants. The city was more insular at that time, and frowned upon Hindi speakers from outside. But that forced Kumar to pick up Tamil words faster, and made the move to Chennai a little easier. He doesn’t stand out that much here. But the tag of ‘Hindi-karan’ remains – a catch-all label for all North Indians in Tamil Nadu.

“If I had work in Bihar, why would I come here?” said Kumar, adding that apart from farming work in his village, Bihar had nothing to offer him. “I earn more money here than I could anywhere else. What other option did I have?”

Kumar earns anywhere between Rs 20,000 and Rs 25,000 a month, double than what he would earn anywhere in North India. He doesn’t plan on leaving Chennai anytime soon, especially since he needs to save up for his sister’s marriage.

The joint where he works has proud signage in bold Tamil letters, with no English or Hindi translations underneath. No native Tamil speakers work at the Tamil-owned shop, though. All three workers are from Bihar, and in between serving customers, they speak to each other in Hindi.

Multi-language signage has been targeted in the past. As recently as February 2025, DMK party workers blackened Hindi letters on signboards at railway stations such as Sankarankovil, Kadayanallur, and Pavoorchatram. In addition to the vandalism, the group also raised slogans against Hindi imposition, resulting in the Railway Police Force launching an investigation.

A 2022 Press Information Bureau report estimated the number of migrant workers in the state at 34.87 lakh, a three-fold increase since 2015-16, when a Tamil Nadu Labour Department survey put the number at 10.2 lakh. The department is in the process of conducting another survey to gain a more accurate understanding of current numbers.

Also read:

Demand for non-Tamil workers

The influx of migrants has led to an increase in the demand for Hindi-speaking managers who can communicate with Hindi-speaking employees. G Sathish Kumar, a Tamil manager at ST Couriers, a Madurai-based logistics company, oversees 150 migrant workers from Bihar, Assam, and Odisha.

Sathish sits in the shade, looking over at six freight trucks parked in the compound. Since most delivery work happens at night, some migrant workers are asleep in the makeshift shed at the far end of the compound.

“You can get by with Hindi in Hyderabad and Bangalore too. If you know Hindi, you can go anywhere,” said Sathish, adding that Tamil is only spoken in Tamil Nadu, which limits its use for professional mobility.

Having grown up in a military family, Sathish is used to moving across India. He attended CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) schools in Punjab, Assam, Karnataka, and Delhi. While he learned Tamil from his father, he was primarily educated in English, Hindi, and Sanskrit.

You can get by with Hindi in Hyderabad and Bangalore too. If you know Hindi, you can go anywhere – G Sathish Kumar, a Tamil manager at ST Couriers

But it works both ways. Hindi-speaking workers understand a spattering of Tamil to communicate better on the job. Some of the employees working the day shift shout across the factory floor, asking if the order is ready or whether packing has been completed in Tamil, while speaking their mother tongue to each other in private.

Many have just arrived within the past year, but none have learned to speak it fluently like Sunil Kumar, who started working with ST Couriers in 2020. Sunil, 22, migrated from Bihar after a friend referred him for the job. A starting salary of Rs 12,000 was too good for him to turn down.

“Sathish recommended that I learn Tamil,” said Sunil, adding that his manager helped him transition into the new role with ease. “He said, once you learn, no one can tell you anything about living in their state.”

Sunil experienced the hospitality first hand. When he travelled across Tamil Nadu for work, he found that residents were always surprised to learn he was from Bihar. After hearing him speak in Tamil, they couldn’t believe he was from outside the state. That’s how natural his Tamil sounded.

“I have so many friends in Tamil Nadu, we even insult each other in the local language,” he said, laughing at the abuses hurled his way in jest. “They never get serious about it, they know I’m their friend.”

Working with Tamil drivers allowed Sunil to pick up the language fast. Necessary phrases like ‘take the truck down this road’, ‘reverse the vehicle’ and ‘come, let’s go there’, made their way into his vocabulary first.

He can’t read Tamil but said this isn’t much of a problem because most the addresses and delivery details for most orders are written in English. In fact, since a lot of orders come from Mumbai to Velammal Hospital and Medical College in Madurai, he often speaks Hindi with the senders and receivers to coordinate the logistics.

According to G Sathish Kumar, the manager, Tamil workers know only a few words in Hindi, but don’t hold any resentment toward their North Indian colleagues. Knowledge of and engagement with Hindi also reveals the class divide in Tamil Nadu, he said.

“Only the lower and middle class in Tamil Nadu don’t know Hindi,” said Sathish, shaking his head in disappointment at the state’s political climate. “The rich guys send their children to CBSE schools but oppose Hindi for political reasons.”

Also read:

Student discomfort

From competitive exams like the UPSC (Union Public Service Commission) and SSC (Staff Selection Commission) to career advancement, many students see Hindi as a practical tool rather than a political issue. But some complain about the unfair advantage native Hindi speakers get in these government exams.

“After clearing the first SSC exam, I had difficulty in the group discussion,” said M Jeevan Kumar, a 22-year-old IAS-aspirant studying at Aram Academy in Chennai. “Everyone was talking in Hindi or English, which made it difficult for me to put my point across.”

Kumar took Hindi classes in his primary school but shifted to a Tamil-medium state board school after. He picked up a bit of Hindi while staying in Noida for eight months for a corporate job, but felt out of place not knowing the language.

“Even in my one-on-one interview for the SSC exam, the interviewer was more comfortable with Hindi,” he added, acknowledging that regional language speakers are treated differently in these exams.

Mohamed Nihmathulla, 22, from the same IAS academy, went to a Muslim school in Muthukulathur, Tamil Nadu. The school was English-medium but also taught Tamil, Hindi, and Urdu to students. Nihmathulla, however, is mainly comfortable in Tamil, which proved to be a disadvantage for him during UPSC Prelims.

“The Prelims are conducted in either English or Hindi, which becomes a problem for me,” said Nihmathulla, adding that he regretted not knowing Hindi proficiently. Although students can write their answers in their regional language, instructions are often in English and Hindi. “But my wish is that the exam is conducted in Tamil, that would have been the easiest for me.”

There is a small city vs big city divide in the hostility toward Hindi in Tamil Nadu.

While students in Chennai are more open to learning the language, those at the American College in Madurai are dead set against learning it.

“No Hindi” said Kumaran K, studying for a Bachelor’s in Commerce, with a hint of annoyance in his voice. “Why force us to learn it? I have no need for it, I want to stay in Tamil Nadu all my life.”

Other students nodded in approval but refused to chime into the discussion. Some of them wanted to work in accounting, others in exports and IT, but all said Tamil Nadu had enough jobs to satiate their ambitions.

Outside Rajaah’s Resto-Café, the university canteen, a mechanical engineering student is pushed forward by his friends, who have nominated him as the group’s unofficial spokesperson. The group speaks no Hindi and isn’t too confident in English either. All its members attended Tamil-medium schools in areas surrounding Madurai.

“Although I need to improve my English, I know it will happen once I move to Dubai,” he said, adding that going abroad to work has always been his dream. “But learning Hindi has no value for me.”

He doesn’t need to speak Hindi in Madurai. And whenever he travels outside the state, his English skills help him get by. Though he admits that an extended period in North India would require him to pick up basic Hindi.

“Let it come to me naturally then,” he said, adding that he didn’t see the need to make it compulsory in Tamil Nadu.

Also read:

Language teaching

Hindi is taught at over 1,700 CBSE schools across the state, following the Centre’s three-language system push. It’s often chosen as the third language, but the learning is academic in nature with not much importance placed on speaking or scoring well in the exams.

Latha Naidu, 48, teaches online spoken Hindi to children in Tamil-medium CBSE schools. She lives in a multi-story house located in a newly developed, middle-class neighbourhood in Umachikulam, Madurai.

Her family belongs to the Telugu-speaking Naidu caste, but she was born, and raised predominantly, in Madurai. A large, flat screen TV in the background blares a soap opera on Star Vijay, a Tamil television channel. A military brat, she learned Hindi by living across India.

Since moving back to Tamil Nadu three years ago, she saw the demand for spoken Hindi rise in her area. Parents complained that their children couldn’t speak any Hindi despite it being a subject in their CBSE schools.

“There is a difference between learning Hindi in school and actually speaking it,” said Naidu. “Parents realise the language is important for their kids’ future as they travel out of state.”

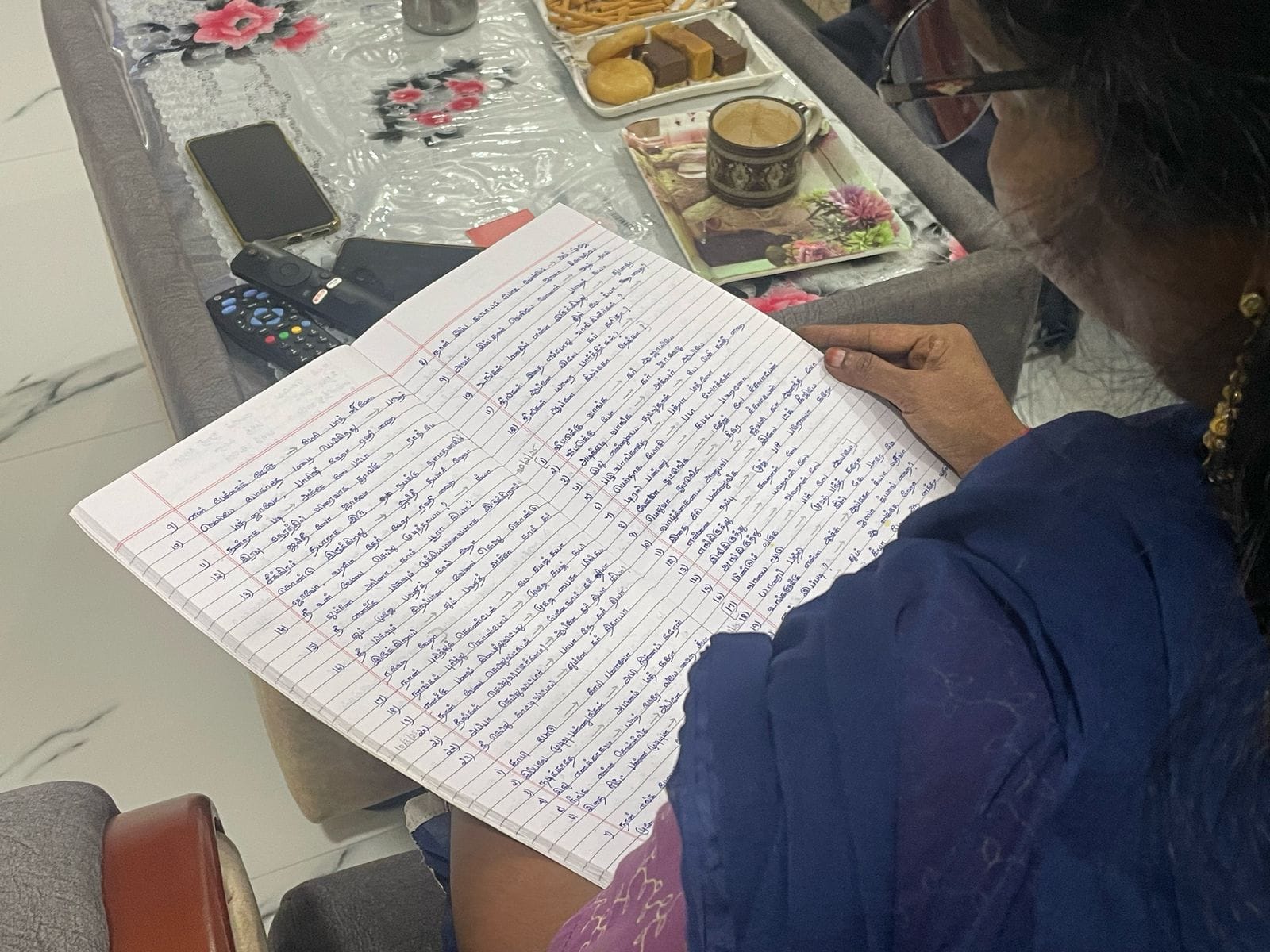

Latha keeps neat, well-organised teaching notes, carefully divided into sections like numbers, body parts, greetings, and family members. Each Tamil word is paired with its Hindi translation, written in the Tamil script. Since Latha can only speak Hindi but cannot read or write it, she phonetically transcribes the Hindi words in Tamil, making it easier for her students to learn.

The headquarters of the Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha (DBHPS), set up in 1918 by MK Gandhi to propagate Hindi in South Indian states, lie in the heart of Chennai. The centre offers four main levels of Hindi examination along with three additional higher-level certifications.

In 2023, 4.14 lakh students from Tamil Nadu enrolled at DBHPS for Hindi classes, compared to 3.73 lakh in 2022 and 3.47 lakh in 2021. The previous year, 2020, saw 4.85 lakh students enrol, on account of the Covid-19 pandemic and closure of schools. According to DBHPS secretary MG Guttal, the increase in demand is largely due to the state’s two-language formula, which excludes Hindi from the syllabus.

In 2022, DBHPS launched online spoken Hindi classes. With a basic and advanced level, the course is aimed at adults who want to learn Hindi for the workplace, both within the state and for traveling outside. The one-month course, priced between Rs 4,000-4,5000, is 45 hours-long and covers basic pronunciations all the way up to common conversational situations.

S Vijaya, 65, a Chennai-based teacher conducting online classes through DBHPS, said that Tamil Nadu is being portrayed wrongly by the media. There are a lot of people here who want to learn Hindi, she stressed.

“We get doctors, IT professionals, and even yoga teachers who want to learn the language,” said Vijaya, who has been teaching Hindi since she was 18 years old.

Dr Sivakumar, a cancer specialist based in Chennai, took Hindi classes from Vijaya for three months. Growing up in the 1980s meant exclusively Hindi content on television, which allowed him to gain a basic understanding of the language. He attended an English medium school but took classes on the side at DBHPS, up to the third level. Although he could speak Hindi, he had difficulty with grammar and completing sentences, which prompted him to sign up for the online classes.

“We have one or two patients a week who come from Northeast India and even Bangladesh and speak a bit of Hindi,” said Sivakumar, adding that he needed to learn phrases like ‘What are your symptoms?’ and ‘What medication are you on?’ in the language. “The rapport is better when you speak to patients in their mother tongue.”

Caste dynamics play a part in picking up the language, too. Vijaya grew up in a Brahmin-dominated region of Chennai, where communities have less antipathy toward Hindi because of their affinity toward Sanskrit. According to her, the desire to learn Hindi was more prevalent in South Chennai as compared to the industrial area of North Chennai.

But the common thread tying students, teachers, professors, businessman, and even migrant workers across the state is this: Hindi should never be made compulsory. No student can be forced to learn a language, let alone three.

“NEP does not impose any language on any state. It only suggests three languages to be taught in the schools,” said Vinoj P Selvam, the state secretary of BJP’s youth wing in Tamil Nadu, adding that the third language can be any Indian language and not necessarily Hindi. “But political parties are raking it for their political agenda.”

However, Hindi does tend to dominate as the third language. PTR pointed to the Kendra Vidyalayas and CBSE and ICSE board schools across the state that have adopted Hindi as the default choice.

“We have seen what Hindi has done to the dialects of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh,” said PTR, referring to what is now called the Hindi heartland. “All the native languages there have all but disappeared – subsumed by the Hindi monolith.”

Udit Hinduja graduated from Batch 1, ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)