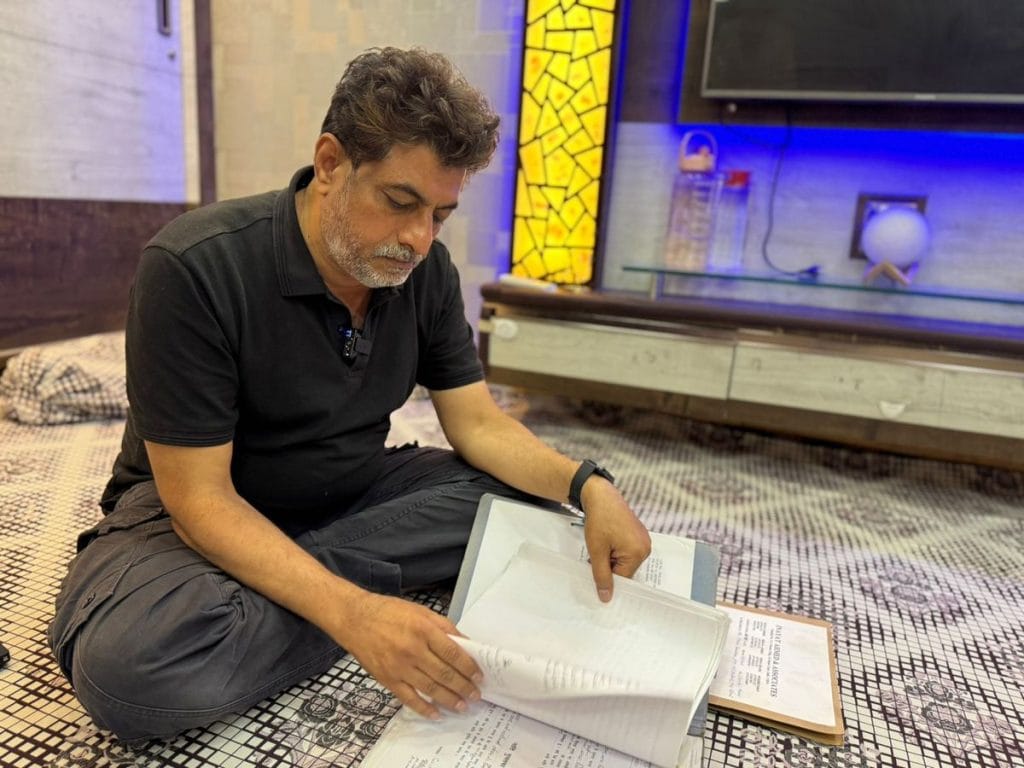

New Delhi: Every morning since last Thursday, Mohammad Aftab has called his lawyer, friends, and former co-accused with the same question: “Is the case really over? Or is it a joke?” Newspapers, social media, and daily reassurances do little to convince him.

It’s been five years since he was accused of sheltering foreign members of a Tablighi Jamaat congregation during the COVID-19 lockdown. Now, even after the Delhi High Court quashed the cases against him and 69 others, Aftab can’t stop looking over his shoulder.

“When you’re falsely accused of a crime, you become hopeless. So much so that it wouldn’t be surprising if tomorrow you were thrown in jail or labelled a terrorist,” he said, lost in thought as he stroked his long black beard that flowed down to his chest.

The verdict has travelled fast through the narrow lanes of Old Delhi’s Turkman Gate and Daryaganj, bringing relief to the families, but a sense of unease lingers.

It took half a decade and a maze of court hearings for 70 Muslim men to be cleared of various charges filed in 16 FIRs, ranging from violating COVID orders to spreading infection. On 17 July, the Delhi High Court finally closed the cases, calling them an “abuse of power” and “not in the interest of justice.”

But for those accused, life came to a standstill. Branded as “super spreaders of COVID-19” and accused of waging “Corona Jihad,” they spent five years under the shadow of FIRs, court proceedings, and public suspicion.

The nightmare began in March 2020, when thousands of members of the Tablighi Jamaat, a conservative Islamic missionary group, gathered at the group’s headquarters in Nizamuddin ahead of the lockdown. When COVID cases began to rise, the gathering was quickly blamed for spreading the virus. FIRs were filed in as many as 11 states against 2,765 Tablighi members. Within a year, high court after high court, from Bombay to Allahabad, dismissed these cases. But in Delhi, for the residents who allegedly opened their doors to congregants, the process dragged on.

I kept begging them to let me go, telling them I’d just lost my son. But they didn’t listen

-Mohd Aftab

Many of the accused said they were asked to plead guilty in court to end the long-winding legal ordeal. Their reputations were at stake, and it even made them fearful of expressing their religious identity openly. For them, the fight wasn’t just against legal charges, but about reclaiming dignity after becoming the fodder of a trial played out on television and across social media. Even now, with the case closed, many of them say they hesitate to call themselves Tablighis.

Their lawyers, too, had to deal not just with a small mountain of FIRs and chargesheets, but repeated tactical delays.

“It’s unfortunate that it took five long years to deliver justice in this case. The delay wasn’t because of the Delhi High Court—it was due to the state repeatedly employing delay tactics,” said advocate Ashima Mandla, one of the two lawyers representing the men. “Every time the matter was listed, it was the state counsels who failed to comply with court directions. If the court had asked for a status report, it would take the state nearly a year to file it, often citing reasons like a change in counsel.”

On top of this, the pressure to settle the case was constant, according to Mandla. The men, however, weren’t willing to do so.

“The state kept stalling, and then, in court, they’d suggest simply paying a fine to close the matter. But for the people fighting this case, it wasn’t about the fine. It was about restoring their honour, which had been publicly besmirched.”

Also Read: ‘No whisper of COVID infection,’ says Delhi HC, as it quashes 16 FIRs in Tablighi Jamaat case

A life interrupted

Last April, when Shafiquddin Malik, 58, walked through the narrow lanes of Fatak Teliyan in Old Delhi, he saw a policeman speaking to a shopkeeper in the distance. His immediate reaction was to rush home and lock his wife and children inside a room. Hours passed. The police never came.

“He came home running and shouted, ‘The police are coming again. Maybe they’ll arrest me. You all stay inside,’” recalled his wife, Saira Shafiq. That was the day the family realised something had changed in him.

“We understood he had taken the case, and the humiliation at the police station, to heart. He had become fearful,” said Saira, who runs a cooking page on YouTube.

The last five years took a heavy toll on Malik. He lost his mother, whose final wish was to see her son cleared of all charges. He slipped into depression—and the drawer in his almirah slowly filled up with court files besides his medications.

“I’m happy that I’ve finally been cleared of all the false charges,” Malik said quietly. “But who will return these five years to us?”

Once a carefree man, Malik began navigating his social life with uncertainty. Each unknown call panicked him, every knock at the door raised his heartbeat, and court dates kept him on edge. His wife, Saira, prayed five times a day when he stepped out, even if it was just for personal work.

In these five years, one thought kept disturbing me: Is this happening because I’m a Muslim? I have so many Hindu friends. No one ever made me feel that way. But suddenly, it felt like everything had changed

-Shafiquddin Malik

“I used to ask Allah to ease his suffering and take away his future troubles,” she said.

Before the case, Malik spent weekends visiting friends and relatives, and chatted with extended family over video calls. Now, he’s a recluse. The family’s plans to shift to a better locality, away from the littered lanes and stench of open drains, were shelved.

“It’s better to live here within the community. At least you feel protected,” Malik said.

He had always taken pride in being a law-abiding citizen. A graduate of Delhi University, he runs both a school in Jaffrabad and a chemist shop in his neighbourhood. His children, he says with a proud smile, are all well-educated—one daughter is a PhD scholar, another a lawyer, and his son holds an MBA. But now, he’s begun to question his place in society.

“In these five years, one thought kept disturbing me,” he said. “Is this happening because I’m a Muslim? I have so many Hindu friends. No one ever made me feel that way. But suddenly, it felt like everything had changed.”

And Malik wasn’t even associated with the Tablighis, he insisted.

‘Followed the PM’s orders’

A day after Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the nationwide lockdown in March 2020, police came to the Choti Masjid near Malik’s home and removed 11 foreign Tablighi Jamat members staying there. The men, from Malaysia and Indonesia, were taken to a quarantine centre.

Malik, the sadar of the mosque, said the Markaz in Nizamuddin had sent the foreigners to stay there a week before, as was a common practice. Members of Tablighi Jamaat, founded in 1926-27 by Maulana Muhammad Ilyas al-Kandhlawi in India, are regular visitors.

Foreign nationals visit Nizamuddin every year and are housed at various mosques, confirmed Markaz counsel Fuzail Ahmed Ayyubi.

“When the lockdown was announced, the Prime Minister said everyone should stay where they are. That’s what we did. We didn’t move them. We kept them where they already were,” said Malik.

But the very next evening, while he was having dinner with his family, there was a loud thud at the door. It was the police. As sadar of the mosque, Malik was asked to accompany them for questioning.

At the police station, Malik and other members of the mosque committee were made to squat on the floor in front of the officers. Then they were handcuffed.

“The police started abusing us, took away our phones,” Malik said. “We kept asking what our crime was, but there was no answer.”

Bail was eventually filed, and the men were released. But the phones were never returned. A month later, Malik and the others went back to the police station to request them. Instead, they were met with more abuse and threats of a fresh case.

“It was pure harassment by the police. They made us sign a blank sheet,” said Malik, pointing to a document where his profile is written in Hindi.

It reads: “Saifuddin Shafiquddin Malik Malik is an uneducated barber associated with the Tablighi. He has been hosting them.”

Malik laughed bitterly.

“Everything written here is a lie.”

Guilty of ‘humanitarian gesture’

Advocate Ashima Mandla fields a stream of calls in her brightly lit Hauz Khas office, furnished with a green sofa and an antique-style clock. Some call to congratulate her, others want interviews or meetings. She has just won a case that became a COVID-era flashpoint — one that seemed like it would never end. Now, she’s something of a celebrity.

On her Apple desktop, a folder titled ‘Tabligi’ is filled with notices, summons, and chargesheets from day one.

Mandla recalled how the focus pivoted from blaming foreign nationals for spreading the virus to targeting those who had hosted them.

“It was a case of flawed investigation and unsubstantiated claims,” Mandla said, laughing.

It was alleged that the accused had violated Section 144 (joining unlawful assembly by hosting a religious congregation.

“But the claim was about housing foreign nationals — and the prohibitory order never mentioned housing. It only restricted gatherings,” Mandla pointed out.

Their offence was that they showed some humanitarian gesture by housing foreign nationals who would not have any other place to go when the entire country was put under lockdown

-Ashima Mandla, lawyer

The 70 accused were also booked under Sections 188 (disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servant), 269 (negligent act likely to spread infection), and 270 (malignant act likely to spread infection) of the IPC, as well as the Epidemic Diseases Act and the Disaster Management Act. Yet the police failed to provide any evidence or prove any charge, said Mandla.

That’s also what the Delhi High Court noted.

“[T]there is not a whisper in the FIRs or the Chargesheets that Petitioners were found COVID-19 positive or they had moved out negligently or unlawfully with intent or knowledge to spread the disease of COVID-19, which was dangerous to human life, the court said.

It also added that the question of “human rights” came up as the movement of the congregants was curtailed because of the lockdown, due to which they had to stay in the Markaz.

“They were helpless people, who got confined on account of lockdown,” the court added.

During the course of five years, Mandla recalls how her clients were on the verge of giving up. One of them, Abdul Wahid, was especially persistent with his calls.

“He wanted to visit his daughter in the Middle East but couldn’t procure a passport because of the case,” said Mandla.

Another client, she says, called her saying he was losing patience and wanted to plead guilty. It was her constant reassurance that kept them going.

“In the end, I just want to say that their offence was that they showed some humanitarian gesture by housing foreign nationals who would not have any other place to go when the entire country was put under lockdown,” said Mandla, adjusting her spectacles.

Also Read: Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir are branded as kafirs, boycotted, spat at. They hide, pass as Sunnis

Stigma and suspicion

Mohammad Aftab was grieving the loss of his 9-year-old son when the Delhi Police came knocking. They asked him to come along for questioning.

“My son had died. I hadn’t stepped out of the house for a week. I had no idea what was going on,” said Aftab, who identifies as Tablighi.

It was at the police station that he learnt that the Choti Masjid, where he was a committee member, was under scrutiny for hosting Tablighi Jamaat visitors. But he couldn’t process any of it.

“I kept begging them to let me go, telling them I’d just lost my son. But they didn’t listen,” he said, his shoulders drooping as he recalled the incident.

Like the mosque’s sadar, Malik, Aftab was booked in multiple FIRs. But the way he was treated by those around him bothered him even more. Relatives began to distance themselves, neighbours whispered. When he walked through the lane, people pointed, murmuring that 16 FIRs had been filed against him.

“They didn’t want to associate with a criminal,” Aftab recalled. They’d say, ‘Ab isse Allah bhi nahi bacha sakta’—Even Allah can’t save him.

Wearing a brown Pathani kurta, with his trousers hitched slightly above the ankles, and a matching designer skullcap, Aftab recounted the questions police shot at him:

“They asked, ‘What do you do in the masjid committee?’ I said, ‘We take care of repairs and maintenance. Whether Tablighis stay or not—that’s decided by the Markaz.’”

The legal battle also gutted his business. Every year, Aftab would travel to Dubai, buy clothes, and sell them at Meena Bazar. But the criminal cases barred him from flying. He was left to rely only on his AC sales and repair shop.

“I kept telling Allah, you’ve given me this trouble, now help me live through it,” he said, wiping his face with the cloth draped over his shoulder.

But what kept him awake at night were news reports of Muslims in India being arrested on terrorism charges. On such nights, he couldn’t sleep.

“I was always afraid — what if I was next?” he said. “I’m also a Muslim, and I have a long beard.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)