Kaithal: It was just like the climactic scene from the 2016 Marathi movie Sairat. The bride’s younger brother had come to visit the newly married couple on 18 June. They were sipping tea in her village home in Haryana. Suddenly he pulled out a pistol and shot her. She ran toward her room but collapsed at the doorway. Twenty-year-old Komal Rani, a native of Keorak village in Kaithal, was a Gujjar and had married Anil, a Dalit, just four months ago. She was killed by her 17-year-old brother.

Minutes after the killing, the brother turned on Instagram and broadcast a live video. Brandishing the pistol, he boasted, “Brothers, listen to me. I have done it. I have killed the girl who was running away from our house. Anyone who takes a Gujjar daughter will meet the same fate.”

Three hours away, at Narnaul, Parveena, from Dholera village in Mahendragarh, eloped with Vikas from the neighbouring village of Bigopur on 9 June. They broke the social norm of not marrying from the neighbouring village. Now Vikas’ village has been ostracised and boycotted by hers. Their route to the bus stand and highway has been blocked, they have no access to the bank and their shops in Dholera have been forced shut. The villagers demanded that their marriage be annulled through the panchayat, arguing that it had fractured the bhaichara (brotherhood) between the villages.

In Sirsa, Jagdish Singh strangled his 27-year-old daughter Saravjeet Kaur to death for talking to her boyfriend Karan Singh on the phone. Jagdish initially claimed her death occurred due to a “heart attack”. But the father and son finally confessed to killing Saravjeet after their arrest on 19 June. They said the boy was poorer and they did not like him.

In the rural belts of Haryana, a woman exercising her choice continues to be regarded as an act of defiance deserving the harshest socially sanctioned punishment. Three incidents within a month paint a grim picture of Haryana families’ unending assault on their daughters and sisters. At its core lies the ‘honour’ of family, clan and village. A woman’s choice is still the most feared idea in these villages. Anybody who violates the social codes is met with ostracism and violence by their relatives. And the panchayats and villagers often back the families. Many such killings remain shrouded in mystery, they never reach the police station and are suppressed by the panchayat-led consensus of silence.

The patriarchal mindset is deeply ingrained in Haryana—an agrarian society bound by caste and tradition. Despite superficial modernity, the izzat (respect) of family and village still rests upon women.

– Reicha Tanwar, director of the Women’s Studies Research Centre at Kurukshetra University

The central government’s slogans and schemes of ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ have not changed how traditional societies in the state view women. Between 2019 and 2023, 24 so-called ‘honour’ killings have been recorded by the state, said former Haryana home minister Anil Vij in February 2024. Three decades of outcry, activism, social counselling, police action and mainstream cinema’s reflections have not shaken the deeply misogynistic way in which ‘honour’ is measured by rural families. Social activists and academicians argue that official data severely underestimates reality, and demand a proper law to document such deaths.

“The patriarchal mindset is deeply ingrained in Haryana—an agrarian society bound by caste and tradition. Despite superficial modernity, the izzat (respect) of family and village still rests upon women. Without a proper law, ‘honour’ killing cases won’t be accurately documented,” said Reicha Tanwar, director of the Women’s Studies Research Centre at Kurukshetra University.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, 24-year-old Anil Rajput sobbed as he clutched tightly onto a green and pink pillow. He refused to leave the bed—it was where his wife Komal had been moments before she was killed.

“I should have taken her to a different city, but she always said that her parents loved her and would eventually accept our relationship,” Anil whispered between sobs.

A family conspiracy

In the narrow lanes of Nanak Colony in Kaithal district, villagers gathered to mourn Komal Devi’s death. After killing his sister, the 17-year-old fired at her mother-in-law and sister-in-law before Anil rushed downstairs from the first floor, with bricks in hand to throw at him. Then the minor took an e-rickshaw, streamed a live video on Instagram, went to the Kaithal police station and surrendered.

The plan involved the girl’s father, mother and uncle (mother’s brother). The idea was that the minor should attack Komal because he would get less punishment under juvenile law

– Bijender Singh, investigating officer, Kaithal police

Now, at Anil’s home, the curious neighbours have been queueing up to enter the room where the killing took place. Anil’s grandmother, Devi Bai, has been recounting the details of the murder.

“The bedsheet was soaked in blood. We threw it away and I washed the entire verandah. It still makes me shiver,” she said.

Anil and Komal eloped four months ago and went to the Sirsa district court to register their marriage. The couple had been receiving threats since then. They even went to the Punjab and Haryana High Court to seek protection and stayed at the protection house for 22 days.

“But how can you stay at the safe house for such a long time? We wanted to love and live freely,” said Anil, with his head down.

Anil and Komal’s love story was an ordinary one. They met at Ambedkar College in Kaithal, where they were pursuing their Bachelor’s degree in Commerce and fell in love. They would bunk classes, sit in the canteen to have meals together, and speak on the phone discreetly at home. However, last year, when Komal’s family pressured her to marry, they knew they had to take some action.

Threats from Komal’s family were a regular occurrence after their marriage, but eventually, everything felt normal, said Anil. In May, Komal’s minor brother met her and said that he accepted their marriage.

“He even promised to make her parents accept our marriage,” said Anil.

But it was a ploy, said Bijender Singh, the investigating officer from Kaithal City police station. The idea was to gain Komal’s trust before the minor could attack her. The whole family was involved in it. It was the minor’s fourth visit on 18 June. And for the first time, her in-laws and husband left Komal alone with her brother. Then came the sound of gunfire.

“The plan involved the girl’s father, mother and uncle (mother’s brother). The idea was that the minor should attack Komal because he would get less punishment under juvenile law,” said Singh.

While the minor brother has been sent to juvenile detention, Komal’s mother Anita has been arrested. The father and uncle of the deceased are on the run, said the police. Singh said that the minor had procured a pistol from a Facebook friend and that they were investigating the matter.

The bedsheet was soaked in blood. We threw it away and I washed the entire verandah. It still makes me shiver

– Devi Bai, Anil’s grandmother

Also read: Noida has a thriving black market in farmhouses. Delhi’s partying rich are driving it

‘We are trapped’

A dozen men have gathered under the shelter outside a shop in Mahendragarh district’s Dholera village. They had read about Komal’s killing in the local Hindi newspaper and were discussing a pressing matter in their own village: how to annul a marriage and restore their honour.

Taking a drag of hookah, 71-year-old Abhay Singh said that what happened to Komal was the only way to stop the “disease” from spreading.

“Women are innocent; they get easily influenced by men and their ploys of love. The minor boy couldn’t take the betrayal of his sister and had no other choice but to kill her. See, the daughter of our village is walking on the same path,” said Singh, as everyone nodded in agreement.

Singh was alluding to Parveena, who married Vikas from the neighbouring village of Bigopur. The villagers of Dholera have ostracised Vikas’ village.

“No one from that village can cross this road now until they annul this marriage. How can we call them jija (brother-in-law) when they are our brothers,” said Singh, pointing at the stretch of road.

Twenty-four-year-old Parveena and 26-year-old Vikas met at the bus stand, which is now blocked for the boys’ village. Vikas would take the bus to go to his coaching institute in Narnaul, and the girl would take the same bus to her government college in the city. They belong to the same caste and have almost the same economic background, but their crime is that they have fractured the bhaichara of the two villages.

In Haryana’s rural areas, there is a strong concept of brotherhood. People don’t marry their daughters or sons to someone from neighbouring villages, as these villages are considered extensions of their own families. The men and women are treated as brothers and sisters by virtue of being born in those villages. This bhaichara is what has been protecting their women, elders said.

For them, this marriage was a breach of that sacred social contract.

“We used to think girls in our village (Dholera) are protected because all the Bigopur men are their brothers, but the village is attempting to take our daughters. And we will not let this happen,” said 31-year-old Devi Lal Yadav.

Parveena and Vikas sought protection on June 13 fearing threat to their lives amid the warnings and panchayats asking them to get separated and are currently living in a safe house. Dholera village is holding regular discussions and panchayat meetings on getting Parveena back.

Parveena’s father, Sanjay Singh, has stopped meeting people and attending social gatherings. Singh said that his daughter’s act has humiliated him, and he doesn’t have the courage to face people anymore. His daughter ran away on 9 June, Singh recalled.

She had gone to the roadside to collect some farm material when it happened. Since then, Singh has spoken to his daughter twice, but she has refused to return.

After running away from the village, the couple went to Ghaziabad in Uttar Pradesh and got married in a temple.

We used to think girls in our village (Dholera) are protected because all the Bigopur men are their brothers, but the village is attempting to take our daughters.

– Devi Lal Yadav, Dholera resident

In Bigopur, the villagers are trapped. The main road passes through Dholera, the bus stand is located in Dholera, and their shops here have been forcibly closed.

“We have not made a penny last week. We are trapped. We can’t do anything as it will vitiate the already sensitive environment. The boy has done wrong, and we are paying for it,” said Surat Singh, whose grocery shop in Dholera was shut down.

Action against love marriages

It was a mobile phone conversation that got Saravjeet killed. She was talking to Karan, her phone covered with her dupatta, when her father Jagdish caught her. After a heated argument, Jagdish, a farmer, strangled her to death with the same dupatta. Both Saravjeet and Karan belonged to the Kamboj caste, but Karan came from an economically weak family and owned less land.

The next day, on 3 June, Saravjeet was quickly cremated in Najadela Kalan village of Sirsa. A cover story was spread—she died of a heart attack post-midnight—but everyone knew the truth. Jagdish had a story ready—on 2 June, during the storm, the family was awake and picking up items lying in the open when Saravjeet fell from the charpoy (cot) and died.

They would’ve gotten away with it if social activist Kartar Singh hadn’t moved an application to the police over the suspicious nature of Saravjeet’s death. A police team was formed, and her father and brother confessed to killing her during the investigation.

Ankit, a PhD scholar at the University of Wroclaw, Poland, who has done field research on gender and marriages in Haryana, said that he met several villagers and sarpanches who wanted the government to take strict action against increasing cases of ‘love marriages’.

“In Mahendragarh district, villagers told me that young men and women were not adhering to traditional customs, marrying across castes, and running away from villages. They wanted the government to save them,” said Ankit.

This sentiment runs across Sirsa, Kaithal, and Mahendragarh, right down to the Narnaul police line where Parveena and Vikas are seeking protection. Even the police personnel disapprove of the couple’s relationship.

An inspector boasts that he has raised his daughter so well that she quietly married a man of his choosing.

“In our society, we don’t approve of love marriages. As police personnel, our duty is to protect the couple in the safe house, but as a Haryanvi, I know such marriages are a blot on our society,” he said.

Another police officer said that the news of Komal’s killing has reached the couple and now, they are seeking to extend their protection further.

ThePrint tried to meet Parveena and Vikas but they refused.

Also read: UP village kids forced ISRO to bring space lab. Now they use drones, building weather station

The brother’s rage

In Komal’s native village of Keorak, villagers are heaving a sigh of relief. Sixty-year-old Sunita Devi said the family did the right thing by killing their daughter.

“You invest so much in a daughter, educate her, buy her clothes, worry for her, and then she elopes with a man and brings shame to her parents? What should one do with such a daughter?” Devi said as she walked to her house with an earthen pot.

Komal’s father’s brother Suresh Pal is lying on the charpoy in his house. Pal was taken by the police for investigation on 21 June and was released eight hours later. He recalled how Komal’s younger brother started behaving abnormally after she eloped and got married.

“He started talking less. He would hardly come home. He would only say one thing: ‘Either I will kill her or kill myself’. Such was his rage,” said Pal. He did not know of the family’s plot and regrets the death of his niece.

Pal said the villagers don’t let the family live in peace. Her younger sister was about to marry, but the groom’s family backed out after hearing about Komal’s marriage. The minor’s friends started teasing him, and the family restricted themselves to their house because of the gossip in the village.

In our society, we don’t approve of love marriages. As police personnel, our duty is to protect the couple in the safe house, but as a Haryanvi, I know such marriages are a blot on our society

– Narnaul inspector

Pal, who is himself married to a woman from a Scheduled Caste, said that he was unable to find a woman to marry within his own caste. So, instead of marrying from outside the state, he chose to marry a “lower caste” woman.

Decades of killing unborn girls have led to a situation where Haryana men can’t find women in their own caste group to marry. It has spawned a decade-old practice of buying brides from other states. Many bachelors have mobilised themselves as ‘randa unions’ and pleaded with the state government to help them find women to marry. The bought brides who are not treated fairly are also beginning to seek protection and rights.

Short-lived joy

Back in Nanak colony, Anil is haunted by his wife’s memories. He intermittently babbles about her, cries, and then turns quiet.

“She loved chocolates. A day before her death, I got her Dairy Milk and 5-Star chocolates as she was on her period. I even massaged her legs because they were hurting,” said Anil as he cried loudly.

The night before her death, Anil, his brother, sister, and Komal chatted until 3 in the morning.

“She was afraid of ghosts, so my brother was telling her stories. She would flinch and hug me, and we would all laugh,” said Anil, adding that her laughter still rings in his ears.

Anil recalled that when they were preparing to sleep, Komal told him that she was happiest with him and had never felt such joy.

“The joy was short-lived,” he said, sobbing.

A day later, on 18 June, when Komal was shot down at the entrance of the room, Anil rushed to her and held her in his arms as blood oozed from her body.

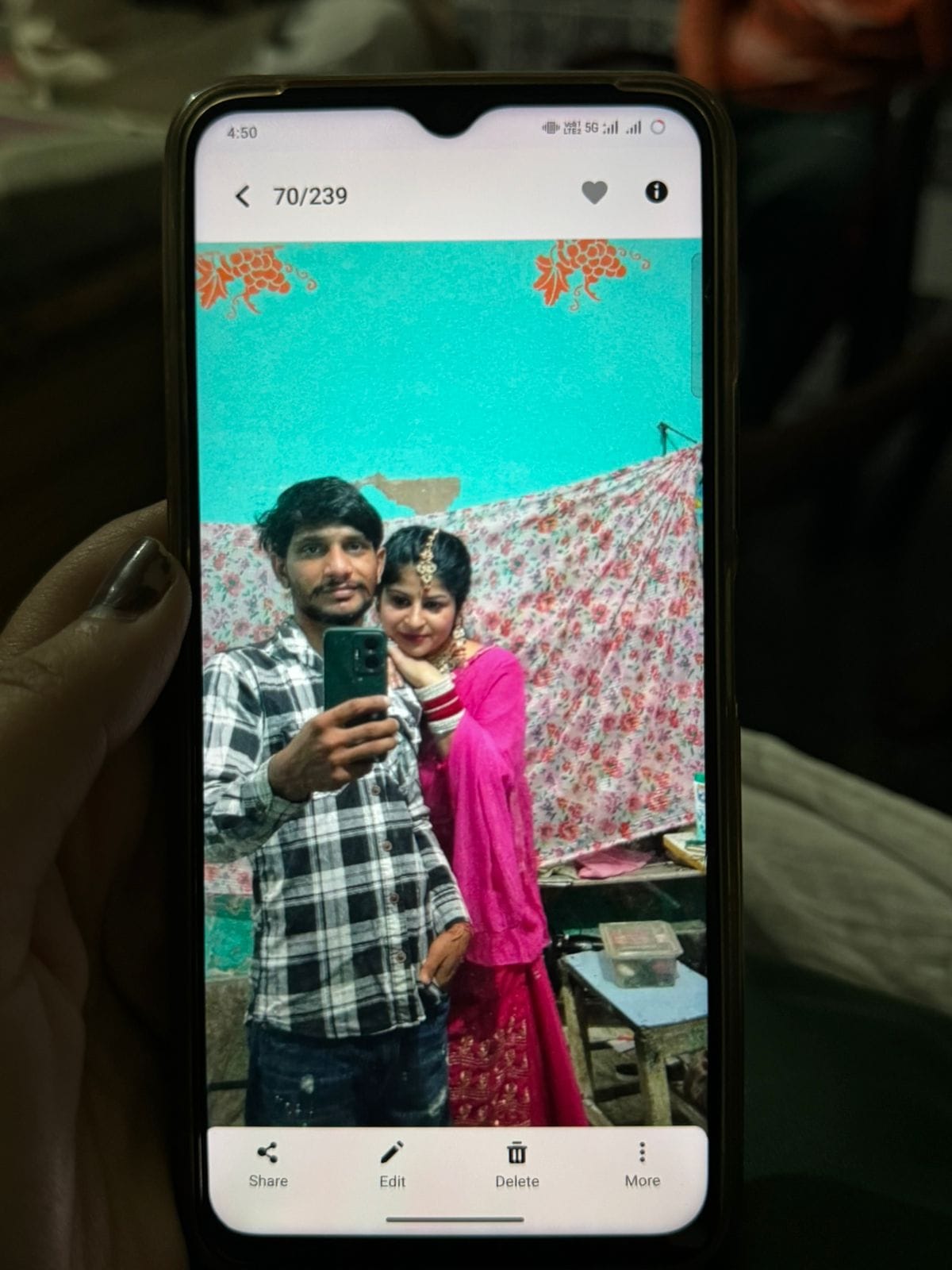

“She smiled looking at me, and then her breathing stopped. She died in my arms,” said Anil, as he kissed her photo on his mobile phone, with a teardrop rolling down his left cheek.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)