Faridkot: In November 2018, a young man touched down at Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport from his honeymoon in Malaysia. It was the beginning of a new life. Little did he know that a Special Investigation Team, probing sacrilege cases in Punjab’s Faridkot, had been on the lookout for him. He was apprehended on the charge of sacrilege against Sikhism. From the holds of his wife’s soft red-bangled wrists, his hands were now in the clutch of Punjab Police in a matter of minutes.

And he won’t be getting out of this chokehold for the rest of his life.

“My life has never been the same,” the accused lamented, requesting anonymity. He was at the Rampura Phul district court in Bathinda for a hearing of his case.

A member of the Dera Sacha Sauda’s state committee, he is one of the many followers of the religious cult, charged by the police for their involvement in the cases of sacrilege reported from Faridkot district between 2015-17. He allegedly masterminded the tearing of the Sikh holy book at Gurusar village in Bathinda district in October 2015.

Sacrilege-accused are among the most hated group of people in Punjab. They have been disowned by their families in newspaper ads and socially isolated by their neighbours. Even Gurdwaras announce against intermingling with them. Today, they lead their lives like social fugitives, never to be seen or heard from—except in the court of law.

It [sacrilege] is murder, and perpetrators must be tried for murder

—Iqbal Singh, resident of Bargari village

Cases arising out of sacrilege—or beadbi—provoke the most passion in Punjab. The accused often suffer vigilante justice from angry members of the Khalsa. They are boycotted by neighbours, stores, the Gurdwara community, and their families live under constant police protection. Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) prescribes only a three-year imprisonment for attempting sacrilege. In Punjabi society, though, it is punishable by death or the complete revocation of a normal life.

In the most recent case, 28-year-old Karam Singh, a daily labourer and Mazhabi Sikh, was lynched to death in Moga’s Mustafa village for allegedly stealing from the donation box of the Gurdwara. An FIR has been registered against 6 people.

Desecration of the holy book is a sentimental topic for the Sikhs because the Guru Granth Sahib is considered to be a living guru. So, an attack on the Granth is seen as an attack on the guru himself.

It has been more than eight years since the first of the nearly 200 sacrilege cases emerged from Bargari village on 12 October 2015, but the anger among Khalsa members continues to simmer. Legal punishment doesn’t cut it for them; they want all the accused to be tried for homicide.

“Beadbi of Guru Granth Sahib at this gurdwara is a sign of our continued ghulami,” said Iqbal Singh, one of the village residents. “It is murder, and perpetrators must be tried for murder.”

Punjabis say these cases are attempts to fracture the social fabric of the state. “I have never seen so many sacrilege cases in Punjab in the past; they are angering Punjabis who feel othered by the central government,” said Dr Pyare Lal Garg, Punjab-based sociologist and surgeon.

Also Read: Lynching to shooting, ‘instant justice’ is on the rise in Punjab’s sacrilege cases

Sacrilege and Punjab

For several years, the pre-Partition Punjab was roiled by violence and protests following the 1924 publication of a pamphlet in Urdu on Prophet Muhammad’s marital life. It ended with the murder of the publisher, Mahashe Rajpal. This led to the introduction of IPC Section 295A, which sought to curb “competitive communalism” where “public peace would be disturbed by large-scale religious hostilities”.

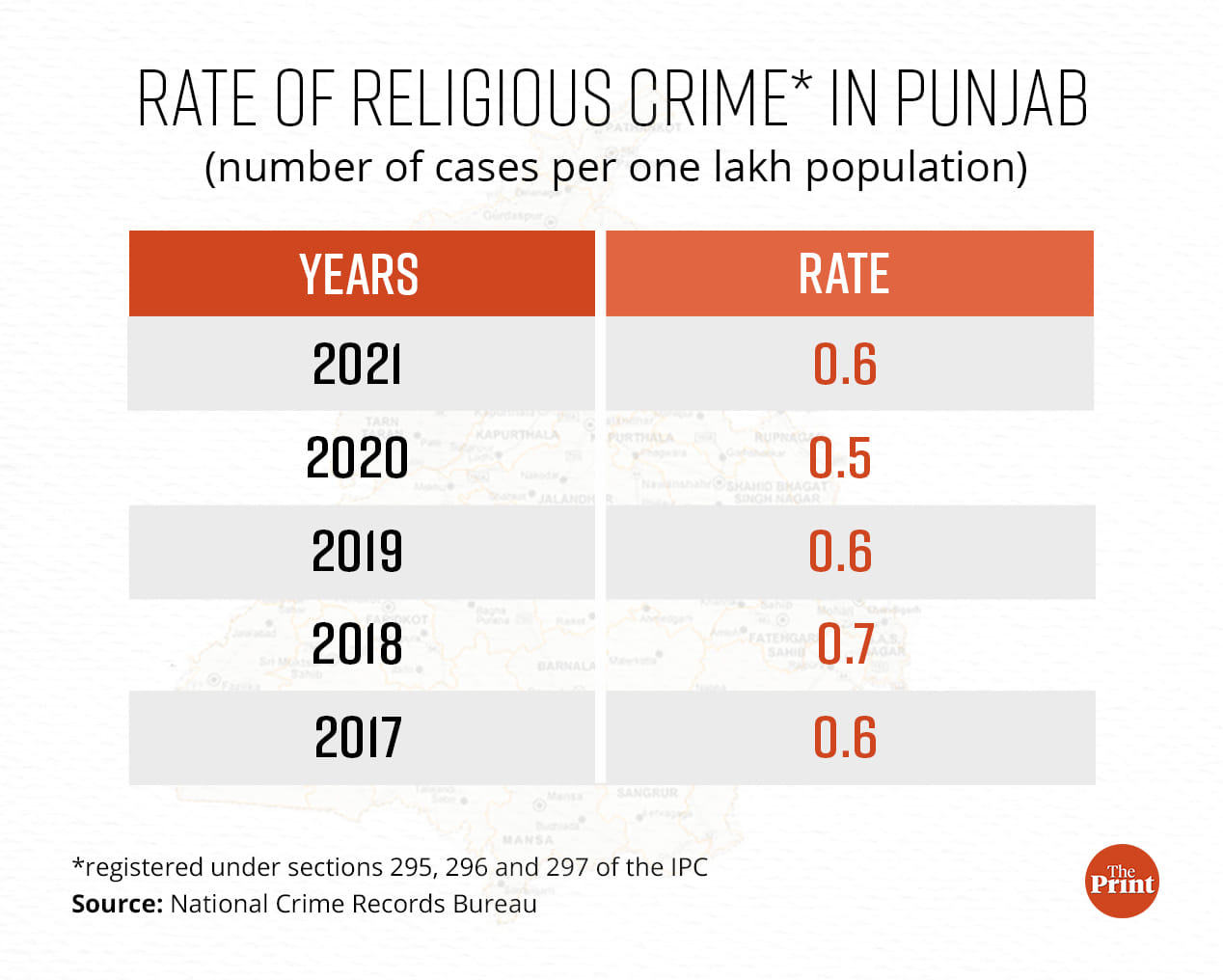

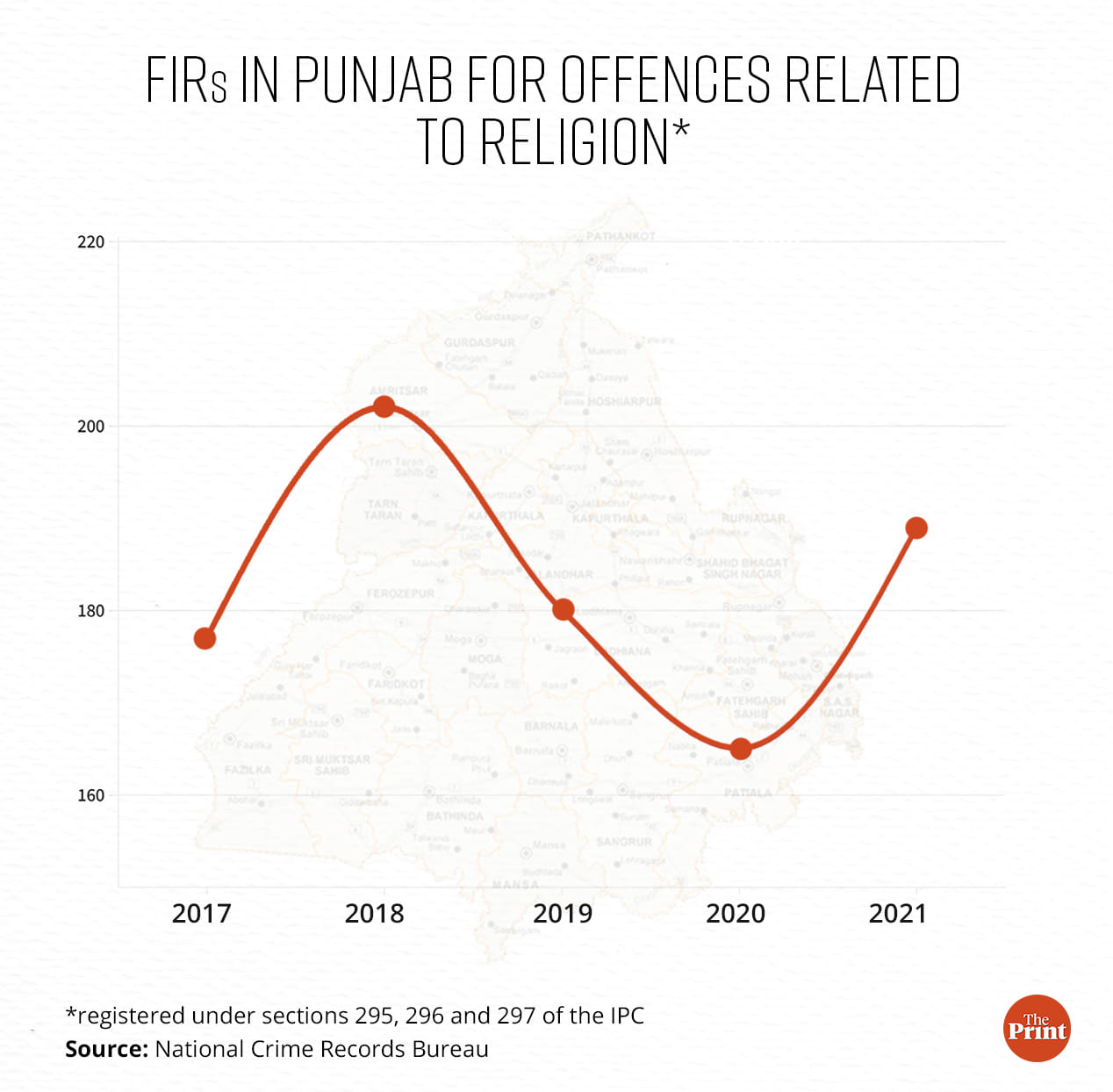

Punjab has consistently recorded the most cases related to religion, according to data from the National Crime Records Bureau. In 2021, the state registered 189 FIRs under Sections 295 to 297 (defiling a place of worship, disturbing religious assembly, trespassing on burial grounds). Punjab’s rate of crime (number of cases per one lakh population) for such offences was 0.6, the highest in India. Next was Goa with a crime rate of 0.5, but in absolute numbers only eight cases have been registered. Maharashtra had the highest number of cases, (286) and a crime rate of 0.2.

Public demand for harsher punishment in sacrilege cases has been heeded by Punjab’s leaders. Based on then-PWD minister Vijay Inder Singla’s motion, the Punjab assembly unanimously approved an amendment to the IPC and the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) in 2018: “Whoever causes injury, damage or sacrilege to Sri Guru Granth Sahib, Srimad Bhagwad Gita, Holy Quran and Holy Bible with the intention to hurt the religious feelings of the people, shall be punished with imprisonment for life.”

Then-Chief Minister Captain Amarinder Singh had clarified in an op-ed that the amendment “does not make unintentional acts punishable, but only targets deliberate acts aimed at creating religious tension in the state.”

While the amendment never received the presidential nod, with the Centre terming it “harsher punishment”, Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann wrote to Union Home Minister Amit Shah in may this year, clarifying the state’s position. Pargat Singh, a senior leader of the Congress Party, said it boggles him why the Centre still hasn’t passed the amendment. “The issue of sacrilege is extremely emotional in Punjab. It is in the best interest of the state and the country if a stricter punishment is given for such grave acts. Only that can curtail it,” he told ThePrint.

Faridkot sacrilege

Gora Singh, the granthi of the gurdwara in Jawahar Singh Sircar village, was woken up from his evening nap on 1 June 2015 by his panicking son—“Papa, babaji is missing. The granth is not there!” The granthi immediately informed the village of the theft through the gurdwara’s loudspeaker.

At first, the villagers were angry and confused. Who would steal the Sikh holy book and why? They remained vigilant, waiting for any news on the whereabouts of the holy book. Months passed but there was no information. And then came September.

The villagers woke up to handwritten posters allegedly put up by the premis (followers) of Dera Sacha Sauda, abusing the Sikh faith. The posters challenged the Sikhs to find the thieves, taunting them with a reward money of Rs 10 lakh if they succeeded. Dera Sacha Sauda is one of the biggest religious cults in India, based out of Sirsa in Haryana. Its leader Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, convicted for rape and murder and currently lodged in Rohtak jail, still enjoys mass following. He is regularly granted parole whenever elections are round the corner.

The posters came up around the time the Akal Takht granted a pardon to Ram Rahim for imitating Guru Gobind Singh in 2007, and amid protests against his film Messenger of God 2.

“Dera premis thought they’re larger than life. Most followers are lower-caste Sikhs who looked for a more equitable, accepting community when caste deeply fragmented the Sikh community. They found solidarity there,” Dr Garg said. “What really irked Sikhs was the political prowess that Ram Rahim was flaunting and how politicians were lining behind them for votes, looking over Sikh issues,” he added.

By October, the stolen Guru Granth was found; its angs (pages), considered body parts, scattered in front of the gurdwara in the neighbouring Bargari village.

A series of similar incidents rocked Punjab in 2015. They were reported from several districts, including Ferozepur, Nawanshahr, Sri Muktsar Sahib, Tarn Taran, and Sangrur. As protests swelled, clashes began to be reported from various places. In Behbal Kalan, two protesters were killed in police firing.

What really irked Sikhs was the political prowess that Ram Rahim was flaunting and how politicians were lining behind them for votes, looking over Sikh issues

-Dr Pyare Lal Garg, sociologist and surgeon

It led to the Badals losing the 2017 assembly election. Amarinder Singh came to power, riding high on the promise of delivering justice in the sacrilege incidents. His government took the matter over from the CBI, which had closed the case, and constituted fresh Special Investigation Teams.

A life less lived

The newlywed accused’s marriage was on the rocks even before it began. Soon after he was arrested from the airport, he was jailed for eight months in a prison in Jagraon city.

His family owned two outlets of Western Union Foreign Exchange in Bathinda. “What should’ve been the happiest time of my life was spent rotting in jail,” the accused said, sitting in his lawyer’s chamber at Rampura Phul district court in Bathinda.

Sword-bearing Nihangs come to court hearings to intimidate us, asking death be upon us

-a sacrilege accused

Soon after his arrest in 2018, the Gurusar village gurdwara announced that he and his family should be boycotted. Even for small grocery needs, his family now needed to go to a shop outside the town. Their foreign exchange outlets, which had been leased from the local gurdwara committee, was taken over and possessions were not released for almost a year. They eventually had to relocate the store.

After the accused got bail, his wife insisted on going to Dwarka in Delhi and starting afresh. “She was scared that someday, I would be shot dead. She didn’t want me to stay here any longer,” he said.

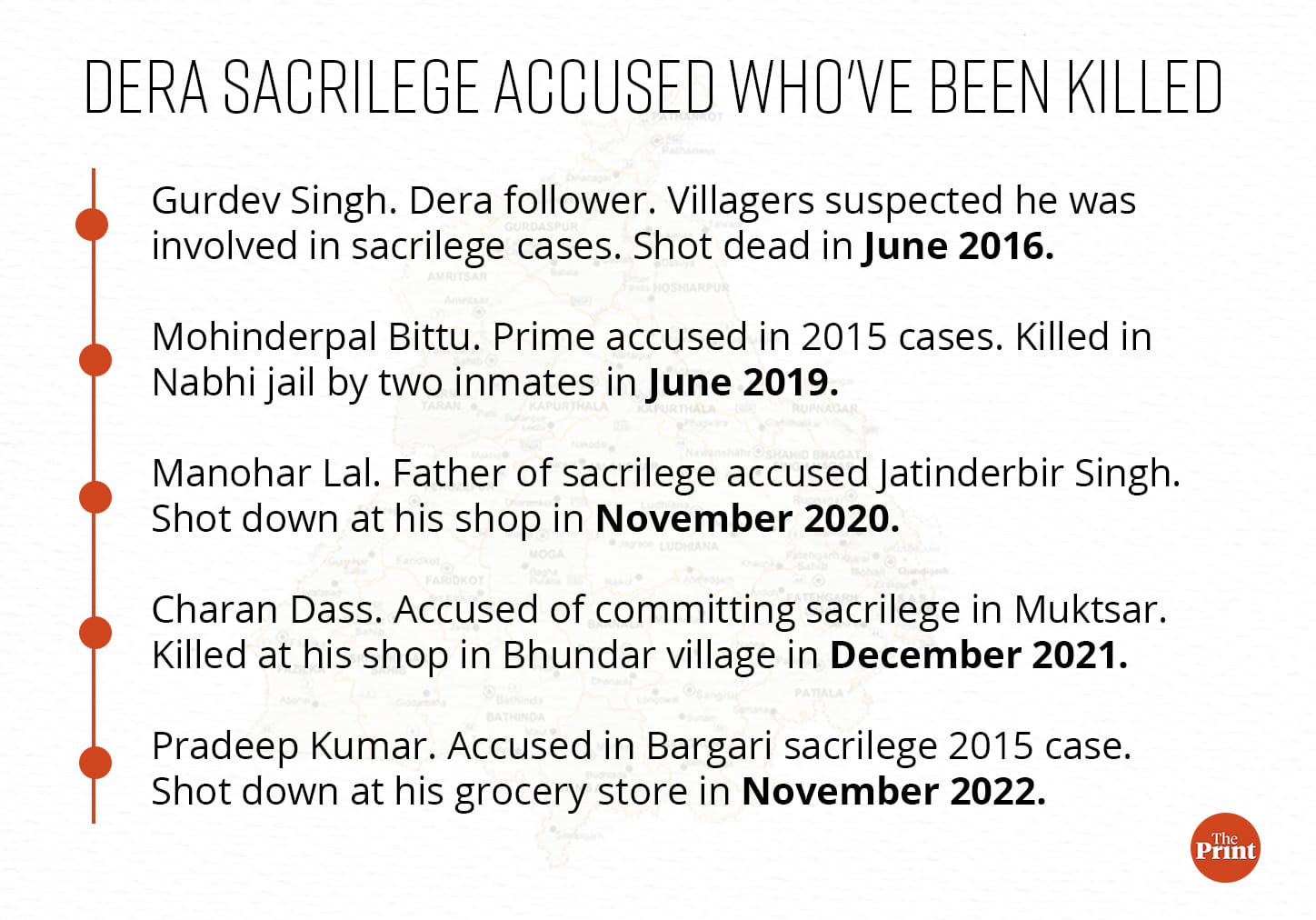

His wife’s fears weren’t unwarranted. In Punjab, the life of a sacrilege accused is untenable. They enter the hit list of local gangs, international dons, and even terrorist organisations. At least five Dera members have already been killed since the first sacrilege case was reported in Bargari in October 2015. The murders are later celebrated on social media. The accused and their families are provided with state protection. Even if the atmosphere in the village cools down, threats from gangsters and international terrorist organisations remain.

Pardeep Singh alias Raju Sodhi was gunned down last year when he was sitting at his grocery shop in Kotkapura. Dreaded gangster Goldy Brar claimed responsibility, writing on Facebook: “Justice had not been delivered in the sacrilege case even after seven years of the incident and despite the government changing thrice in the state.”

Because of the threat to his life, the Gurusar accused comes home only for court hearings in his case, which take place in rooms always packed with angry Sikhs sitting in the audience. “Sword-bearing Nihangs come to court hearings to intimidate us, asking death be upon us,” the accused said.

In 2020, a single-judge bench of the Supreme Court refused to transfer the case, as well as two other sacrilege cases, out of Punjab. The court’s reasoning was that with the passage of time, the anger must have ‘mellowed down’. Two years after the court order, one of the men whose case wasn’t moved, Pardeep was gunned down by six men. Keeping this in mind, the Supreme Court transferred the Bargari case to Chandigarh, saying: “The apprehension of the petitioners cannot be rejected outright as being unfounded and taking an overall view of the petitioners’ plea.”

While the young couple tried to save their marriage in Delhi, back home his father, who was also a prominent member of the Dera Sacha Sauda, leased another property to revive their business. He was shot dead by local gangsters in 2020.

“My father was not even involved in the case, but they took his life mercilessly,” the accused said, tearing up. His father was shot in the head and arms while he was at work. He was rushed to a hospital, where he was declared dead. Gangster Sukha Gill Lamme took credit within hours of the murder. “revenge of sacrilege of Guru Granth Sahib done in October 2015,” he wrote.

His father’s death also marked the end of his marriage. His wife couldn’t bear living under constant duress and filed for a divorce. They legally separated in 2021.

Also Read: Who were the men lynched for ‘sacrilege’ in Amritsar & Kapurthala? No clue yet, say police

Life on the run

Sacrilege accused don’t own phones and don’t stay in Punjab, unless they can’t come up with another option. They are outcasts. Their presence is not accepted. Their life is spent in hiding. They live constantly looking over their shoulders.

“It broke my heart to see all my siblings disown me,” the father of one of the accused in the Faridkot sacrilege case said. “I don’t go anywhere anymore—weddings, cremations, birthday parties. I am not invited anywhere.”

The taint of being a ‘sacrilege accused’ has also spelt doom in business for this family. Their youngest son had to drop out of college and take charge of the carpentry shop. “Nobody comes to our shop anymore. We used to make a lot of money, but the business has suffered a lot since two cops were permanently stationed there,” the accused said. His son is resolute in such times of crisis: “If I don’t step up, who will?”

I don’t go anywhere anymore—weddings, cremations, birthday parties. I am not invited anywhere.

– father of a sacrilege accused

The family’s breadwinners living in hiding also affects relationships, economics, and mental health. The father of a prime accused in Faridkot sacrilege, recalled sleeping in farms after his son was arrested. “I feared that I would be killed,” he said. He took on the responsibility of raising his son’s children. “It’s my time to live in retirement. But I am doing menial jobs in farmlands and somehow making ends meet,” the father said.

A wave of beadbi

The accused in the series of sacrilege cases in 2015 still have a sense of community because they are a part of the Dera Sacha Sauda. The members help them legally and emotionally.

But post 2015, the cases of sacrilege reported from Punjab are not associated with the Dera. In such cases, police and the general public lean into conspiracies involving Pakistan or Khalistani elements and even the Indian deep state.

A 25-year-old man was killed when he attempted sacrilege by trying to desecrate the Guru Granth Sahib with a sword inside the Sanctum Sanctorum of the Golden Temple. Jasvir Singh, who allegedly desecrated the Gurugranth Sahib at Kotwali Sahib in Morinda, was moved from the jail to a hospital in Mansa district due to ‘breathing issues’, but he died in the hospital. Reports mentioned that he had deep wounds all over his body. His house was also targeted in the presence of police in Morinda. The villagers did not allow his cremation to take place in Morinda; his last rites were carried out by the police. A woman was shot dead by a Gurdwara devotee for allegedly drinking alcohol inside a Gurdwara in Patiala. Her family refused to cremate her.

For members of the Sikh community, such retaliation is understandable, if not justified. “A Sikh never attacks unprovoked, but when our Gurdwaras are disrespected constantly and our faith is toyed with, we cannot stay silent. We are emotional, simple people. If the state doesn’t bring us to justice, what’s wrong if we do,” said Budh Singh, a granthi in Bargari village, where the first incident of sacrilege was reported in 2015.

A member of the Akal Takht, on the condition of anonymity, said that in recent years the number of incidents of sacrileges being reported to the highest temporal body of the Sikhs has sky-rocketed. He said a ‘fear psychosis’ has developed in Punjab’s villages around sacrilege. “Times are sensitive, people are overreacting too,” he said.

The member revealed that they often receive ‘false’ cases of sacrilege levelled by parties trying to get a hold of the management of village-level Gurdwaras. “We need to understand this phenomenon. Paranoia has gripped Punjab villages. In Gurdaspur, a man who was lost and trying to find his way was lynched to death for wearing shoes inside the Gurdwara. In Sangrur, there was a case of a 10-year-old. These are overreactions,” he said.

“People register be-adbi cases against granthis (priests) if they rush through a paath. Sometimes Mazhabi Sikhs who come under the influence of missionaries are asked by pastors to throw away Sikh holy texts in their houses, there’s a lot of hue and cry in villages over it,” he said.

This fear is what led to the registration of an FIR against a 10-year-old girl in Sangrur’s Rampura village in June 2020.

A Sikh never attacks unprovoked, but when our Gurdwaras are disrespected constantly and our faith is toyed with, we cannot stay silent

-Budh Singh, a granthi in Bargari village

The Mazhabi Sikh girl used to go to the village Gurdwara regularly for seva. One morning, the local management committee members cornered her. They alleged she had been caught red-handed desecrating the Sikh holy book in the gurdwara’s CCTV.

After questioning her and her family for hours, during which some members had reportedly drawn their swords, the girl was handed over to the police.

According to the FIR, registered on 27 June 2020, members of the Gurdwara’s management committee alleged that the girl had torn “parts 641 and 654 of the Pawan Saroop” Guru Granth Sahib and that they had reached the conclusion after going through the CCTV footage found in the gurdwara.

Then president of the Gurdwara committee, Hardev Singh said that the girl had confessed to desecrating the Guru Granth Sahib. “Not only did we see that happen on camera, she also confessed to us and the police. We had called members from Damdama Taksal to probe the matter, and the girl had confessed to us that she had torn pages of the saroop,” he said.

The villagers insist that they treated the girl and her family with respect and an even temper. “She was a child. We knew she couldn’t have ill intentions. But I am convinced there was someone behind the incident but the police never probed it thoroughly,” an eyewitness said.

He rubbished the reports of sikh clergy intimidating the girl with swords. “A mazhabi nihang had passionately drawn out his sword and yelled that nobody can desecrate guru ji like this, but he didn’t intimidate the girl,” the eyewitness said, “In fact, after learning of her daughter’s actions, her mother started beating her up, which we stopped. We didn’t want to traumatise the child ourselves,” he claimed.

The 10-year-old’s father, Chamkaur Singh, who works as a mechanic and labourer, denies that his daughter ever confessed to the crime, and blames caste-based discrimination for the allegations that have been made against her. He recalls the days they lived in fear, when the village had turned hostile towards his daughter and his family. He said they were in police custody for two to three days, after which they had to seek shelter at a relative’s house for two weeks. “We were targeted because we’re from a low caste, and people didn’t want my daughter in the Gurdwara,” Chamkaur said in a phone interview with ThePrint.

Hardev said the villagers let go of the incident because the girl was small, and also belonged to a poor family. There was no social boycott of the family, a claim Chamkaur corroborates.

The police have now cancelled the FIR, which shouldn’t have been registered in the first place in accordance with the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2015, which details that FIRs shouldn’t be registered against minors for offences with an imprisonment term of less than seven years.

The Gurdwara members say that the case was not proven as the CCTV footage was grainy. But they still insist she did it.

We were targeted because we’re from a low caste, and people didn’t want my daughter in the Gurdwara

-Chamkaur Singh

Singh said the incident traumatised his daughter so much that she went into a shell and stopped talking to her family and friends for some time. “It took her one and a half years to open up again,” he said, and didn’t allow ThePrint to speak to her.

While the atmosphere of the village is completely normal towards his family he still doesn’t go to a Gurdwara. The incident drove a wedge between him and god. “I pay my respects to the guru from a distance now. I don’t feel like going in.”

Questions about the incident still linger in the village. “India takes sacrilege incidents lightly. There should have been a thorough probe. But neither the police was interested in finding out who egged the girl on to commit this crime, nor was the judge,” the eyewitness said. “I am convinced that certain forces that want to harm the Sikh faith are behind the continuous attacks on our gurdwaras.”

Also Read: What is ‘beadbi’ or sacrilege in Sikhism, which sees Guru Granth Sahib as living Guru

Tired of ‘inaction’

The wounds inflicted by the sacrilege incident in 2015 are still fresh in Bargari. The village has turned bitter towards the state for ‘inaction’. Eight years after the incident, the demand for justice is alive in various protests in and around the village. “We won’t be able to sleep peacefully until justice is served,” said Gurpreet Singh, a resident.

Farmers of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh rejoiced on 19 November as the government of India repealed the three farm laws after a year of protests at Delhi’s borders. The farmers could finally go home and sleep peacefully in their houses. All but one—Sukhraj Singh.

On 21 December, Sukhraj Singh started his own dharna near Behbal Kalan, at the spot where his father was killed. He is leading the Behbal Insaaf Morcha— a long-running protest seeking justice for sacrilege cases and the death of his father.

Sukhraj’s father, Krishan Bhagwan Singh, and another villager Gurjeet Singh were killed in police firing during a protest against sacrilege in Bargari Gurdwara in 2015. It took place when the state was on the streets, protesting a wave of sacrilege cases.

Sukhraj and other villagers are constantly sitting vigil in a makeshift tent. It has an AC Unit and a small langar.

“My father was only peacefully protesting the disrespect done to our guru, and he was killed. We are still awaiting justice, and until my father’s killers are arrested and brought to justice I refuse to move from here,” he said.

Sukhraj has been protesting since 2015, but had halted the protests in 2017 when the Amarinder Singh government came to power. “The government has changed thrice, but justice has not been served. Everyone knows it was the police who fired the bullets, and we also know exactly who fired the shots. Yet, no justice has been delivered. Only vote bank politics has been played on the issue,” Sukhraj said.

A special investigation team headed by Inspector General Naunihal Singh is yet to file a supplementary chargesheet in the case.

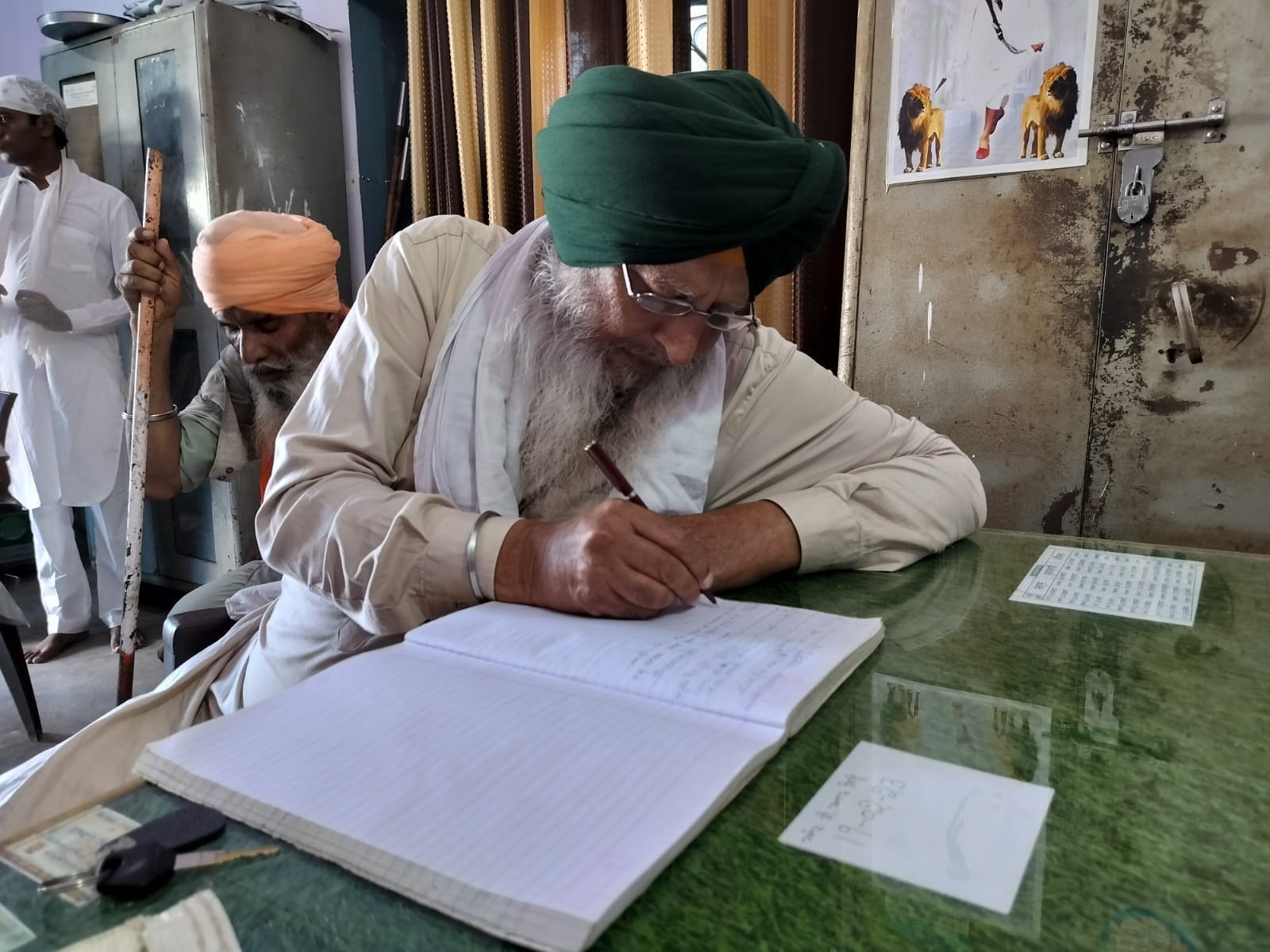

In the meantime, Bargari villagers congregate at the Gurdwara every day and offer prayers.. They then march towards the Bargari Police post, silently, to offer themselves up for arrest in a jail bharo andolan. Five to six villagers have been volunteering to protest this way every day for over 700 days now. The names of people who came forward in seva of the Guru are recorded immaculately in a register.

More than 40,000 people have been arrested in the protest so far, according to record-keepers at the Gurdwara. The protest was started on 1 July 2021 by SAD (A) chief Simranjit Mann, who had offered himself up for arrest. “It is a Gandhian protest, to show how many people the police are willing to lock up before the real culprits are put behind bars for good,” Iqbal added.

Newer cases of sacrilege

On 23 September, a woman entered the Sach Khand Sahib Gurdwara in Jalandhar, stole the sword, and attempted to desecrate the Guru Granth Sahib. She was stopped by the granthi who took the blow on his wrists, deeply wounding himself.

Eyewitnesses said the woman was “uncontrollable” and started flinging the sword manically. The police were promptly called. The gurdwara’s doors were shut with people beginning to gather outside as committee members tried to placate the situation and calm the woman down, president of the Gurdwara management committee, Harcharan Singh said.

The woman, it was later learnt, was going through a rough patch in her marriage and was under depression. She said she acted out of anger and frustration and apologised for creating a scene. “Who starts acting that aggressively when they’re depressed,” a frustrated Harcharan asked, “and why are all mad men coming to Gurdwaras and committing sacrilege here. Why are they not going to temples or masjids? I just don’t understand.”

Harcharan was pointing to a new wave of sacrilege cases being reported from Punjab, where the motive of the crime remains unclear. In many cases, the accused are prima facie declared to be mentally unsound. But this explanation does not sit well with the Sikhs.

I am convinced that certain forces that want to harm the Sikh faith are behind the continuous attacks on our gurdwaras

-eyewitness in a sacrilege case

In the absence of clear motives, conspiracy theories have started to take root. Pargat Singh says the central government is behind the conspiracy, acting like a ‘deep state’. “They want to damage the social fabric of Punjab, which even in its most tumultuous days was never communal,” he said. Dr Garg finds some degree of truth in all the conspiracy theories. “A new hamla has started and I suspect it could be because of Hinduvaadis, or the vested interests of the deep state to create turmoil in Punjab or of foreign agencies, or a mix of all, not discounting political gains,” he said.

Police officers suggest the involvement of Pakistan and Khalistan operatives in Canada. “Punjab is a sensitive border state, and our enemies have long tried to destabilise the state since Independence. Right now, the rise of Amritpal is their way of rousing sentiments here and so are the sacrilege cases,” a senior officer said on the condition of anonymity.

The issue of sacrilege is not just related to Sikhs; it is a cultural issue for Punjabis. Members of all religions, like Jitender Khan, a turban-wearing Muslim, took part in the Faridkot protests. In this labyrinth of politics, sentiments and conspiracies, those accused of sacrilege don’t have to wait for courts to deliver the judgment; punishment has already been meted out to them. Like the Gurusar sacrilege accused, they have accepted that the rest of their lives will be lived in suspension. And no one understands the importance of home more than those on the run.

“I miss restaurants and cinema halls and parties and religious functions and the scent of freshly cut crops,” said the first accused, who has now remarried. “I miss home.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)