Pune: A snarling gold jaguar, a gift from a fellow mogul, dominates Navnath Yewale’s desk, alongside a statue of Maratha hero Shivaji. His shelves bulge with a bevy of awards celebrating his entrepreneurial acumen and philanthropy. His tea empire, Yewale Amruttulya, has Pune hooked, but he positions himself as a humble “chaiwala”. It’s a masterstroke that mirrors the chaiwala-to-chair mythology of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

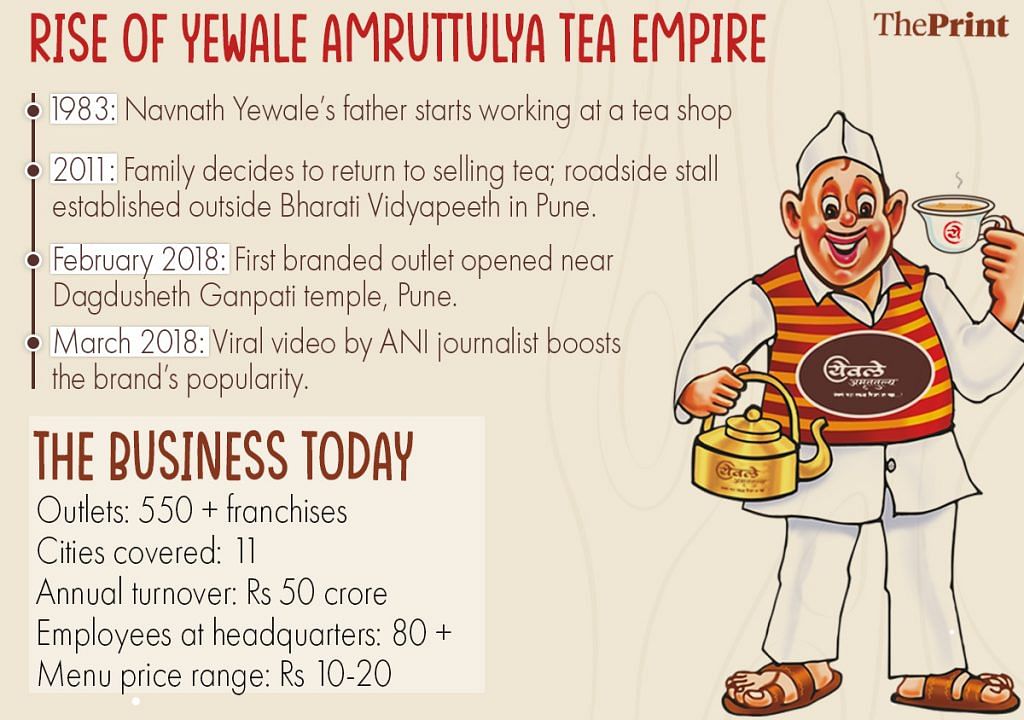

“Chai is an energy drink for Indians,” said 41-year-old Yewale, sporting a conspicuous brand badge on his black coat. With this insight, he’s brewed an empire of 550 outlets with an annual turnover of Rs 50 crore on the back of a Rs 10 cup of tea. He has studied Modi’s political playbook and applied it to his business. His tea is appealing and accessible to the masses, yet retains an aspirational edge.

At a time when urban India obsesses over handcrafted, artisanal, and specialty coffees, the humble, everyday chai has been sidelined. While brands like Chaayos, Chai Point, and Wagh Bakri occupy the premium tea lounge segment, there’s a void for those seeking a hygienic, affordable, and quality on-the-go experience. Yewale Amruttulya is filling this by offering a desi, budget-friendly cup of tea with a hint of flair.

Yewale tea outlets are simple but spotless and the steaming tea arrives in a white ceramic teacup. A regular cup costs Rs 10—what a typical roadside stall would charge—and nothing on the menu is over Rs 20. And Navnath, who runs the business with his four siblings— Ganesh, Mangesh, Nilesh and Tejas—has no plans of jacking up prices.

“My clientele includes not just those for whom Rs 10 barely matters, but also those who count every rupee. It is meant for everyone, and I intend to keep it that way—affordable, hygienic, and tasty,” said Navnath.

After 32 failed ventures, he found gold in tea by emulating Modi’s winning formula, which he distilled into three steps—showing people the problem, offering hope, and being everywhere all the time through an army of franchisees.

In Pune, amruttulya is a common term for tea shops—a portmanteau of the Marathi words ‘amrut’ and ‘tulya’, meaning ‘comparable to nectar’. But Yewale Amruttulya claims to be India’s first “owner-less” business in the segment, charging neither royalty nor commission from franchisees. Instead, they just have to pay a one-time fee and stick religiously to the brand’s recipes and pricing.

The Yewales have now put their stamp across 11 cities in India, and are looking to conquer Northern India. Their dream is to expand from Pune to Paris, and they are serious about world domination.

“We emphasise on understanding the local market before opening an outlet,” said Tejas Yewale, the youngest sibling and head of sales. “Then we can best spread the knowledge about the journey of Yewale tea.”

Navnath has tried his hand at all kinds of work, from selling detergent powder door-to-door to multi-level marketing to mobile phones.

Also Read: Sumit Arora, the small-town dialogue writer who made it big in Bollywood—Jawan to Family Man

McDonald’s to Modi

Navnath Yewale draws inspiration from many sources. If Modi inspired the brand narrative, McDonald’s inspired the smiling mascot. And after a recent trip to Delhi, he’s inspired by how burger franchise Jumboking has managed to open outlets in nearly every metro station of the city.

But even when all this inspiration comes together, he’s particular about his brand’s USP, right down to the last teacup and colour scheme.

The pristine white decor of Yewale Amruttulya’s outlets matches the interior of their corporate office in Kondhwa, Haveli. This office, with nearly 80 employees, is an homage to the brand. It’s decked with brand insignia, an array of white tea cups, TV screens displaying various products and outlets, and an entire wall showcasing the company’s journey from a small tea shop in Pune.

Just like their tea shops, the office has a down-to-earth vibe. Employees, all in the dress code of white shirts and black pants, mostly speak Marathi. New recruits attend in-house sales meetings to learn the ropes of the business. The pace is brisk and efficient.

The all-white colour scheme is deliberate. It evokes a sense of hygiene that encourages customers to step in and order their cup of Yewale Amruttulya tea. Even the mascot wears white.

“We got the idea from McDonald’s mascot, which people love taking selfies with after eating,” said Navnath. “We wanted a mascot like that too.”

But since they lacked funds to design their own mascot, they made an uncle their model. A graphic designer added his flourish, creating the mascot now seen outside every Yewale Amruttulya outlet—a rotund man in a white kurta and pants, with a Nehru cap, holding a kettle.

“That uncle feels happy that he’s immortalised as our mascot,” Navnath laughed.

The family had been running a popular tapri tea stall since 2011, but when they decided to expand into a full-on brand, they had to think beyond just taste and location. For this, they studied Modi’s strategy. First, they tried to show people the problems—roadside tea being served next to open drains and inconsistent taste. Next, they spread word about themselves as the solution with their gloved hands and clean facilities.

The ‘campaign’ element was building a buzz by initially hiding the face of the mascot and then sending invites for the opening, delivered by boys dressed in blazers and ties.

My pockets were torn, and we used to sell vegetables in a cart. But my dreams were always lofty and lavish

-Navnath Yewale

It sparked curiosity among everyone about what the shop might look like, and what kind of tea merited such marketing. They invited Sindhutai Sapkal, founder of the child welfare NGO Mamata Bal Sadan, to open the shop near Dagdusheth Ganpati temple on 9 February 2018.

As the business took off, press buzz followed. A March 2018 video by an ANI journalist about a tea-seller earning “Rs 12 lakh per month” went viral. Yewale claims as many as 8,000-10,000 people starting lining up every day for their cuppa. They opened their next shop the same year and now it’s impossible to go anywhere in Pune without spotting a Yewale Amruttulya outlet.

But some things haven’t changed, and nor are they likely to.

While Yewale Amruttulya is keen on expansion, it’s less gung-ho about diversification. But the menu isn’t static by any means. There’s now a handful of cold teas and simple snacks like cream rolls, khari, and namkeens.

Same-same but different

Whether it’s the Fatima Nagar outlet in Pune or the Indira Nagar stall in Lucknow, every cup of Yewale Amruttulya chai tastes the same, no matter the location or time of day. This consistency is the result of the extensive research and meticulous planning that started right from the launch of the first stall.

“The same cup of chai can taste different if the quality of ingredients is changed or if it’s boiled for too long,” Navnath said.

This prompted him to create kits with exact measurements for two litres of tea and a buzzer to signal when to turn off the stove.

“We get our tea leaves from Assam, sugar from Maharashtra and the milk is locally sourced, depending on fat percentage,” he added.

An important secret ingredient is the small white ceramic cup, inscribed with the brand insignia, in which the tea is served. When Navnath went to place an order with a ceramic dealer, the man mocked him: “Your chai costs 10 bucks, why spend so much on a cup?” But Navnath knew his objective—to build an unmissable brand that made people feel like they were drinking tea at home, in a teacup.

“Even the taste of tea is different, depending on the vessel you drink from,” Navnath said. And his customers agree.

“Of course, we love the taste and the hygiene. But the cup also reminds me of home, and it’s perfect for Snapchat stories,” said one student, part of a group from the Wadia College of Engineering that visits the Budhwar Peth outlet every day, twice.

At 8 am, the shop is bustling with regular patrons and first-timers from the nearby Ganapati temple. They don’t seem to mind that there are no seats—another strategic decision.

“We realised that if we got stools or tables, people would sit and mill around for hours. We sell tea for Rs 10. The idea is to sip it and get on their way,” said Navnath.

The grab-and-go model suits customers just fine. It’s a comforting quick hit of home-like tea without any hassle.

Abhinav Deo has been coming in every day at the Fatima Nagar branch for the past week since his father is undergoing treatment at the nearby Inamdar Multispeciality Hospital. To take a break, Deo sometimes treats himself to a cream roll along with the tea.

“I knew about Yewale tea but hadn’t really tried it. It’s perfect, especially since it’s the same every day. I tried others in this area too, but felt their tea wasn’t as good,” he said.

Nearby vada-pav centres look deserted while Yewale’s outlet buzzes with activity. Tea servers chat with regular customers and often know their usual orders by heart.

While Yewale Amruttulya is keen on expansion, it’s less gung-ho about diversification. But the menu isn’t static by any means. There’s now a handful of cold teas and simple snacks like cream rolls, khari, and namkeens. Their latest launch is a mix of these snacks, crushed together, that, in true desi fashion, can be mixed with tea and eaten.

By and large, long-time customers appreciate that the brand hasn’t strayed far from its roots as a tapri (roadside) tea stall near Bharati Vidyapeeth in Sadashiv Peth.

“Earlier, we drank tea from whichever tapri was nearby, with no loyalty to any seller. But Yewale tea stood out. The staff wore uniforms and played music,” recalled Sayondip Roy, a Deutsche Bank employee who became a regular customer when he was a student at Symbiosis Institute of Business Management in 2018.

Despite the lack of chairs, the spot became a hangout zone. And though new tea vendors came and went, Yewale stayed, he said.

“By our fourth semester, most of those copycats had closed or weren’t doing well,” Roy said. Yewale was smart in just selling just one product.”

Going full circle

Navnath has tried his hand at all kinds of work, from selling detergent powder door-to-door to multi-level marketing to mobile phones. He knew he wanted to make it big, own a BMW, and travel the world but wasn’t sure how.

“My pockets were torn, and we used to sell vegetables in a cart. But my dreams were always lofty and lavish,” he said.

He ended up failing at no fewer than 32 business ventures before life came full circle to tea and the millionaire status he had always imagined.

Born into a large joint family, Navnath was the eldest of several children. His grandfather sold milk from his small dairy in the Camp area of Pune, while his father started running a tea shop around the time Navnath was born in 1983.

Eventually, the tea shop, named Shri Ganesh Amrutullya, started doing well, but the ever-expanding family meant the earnings were never enough for a life of luxury.

Growing up, Navnath wanted to chart his own course. He finished his graduation from Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Mahavidyalay and then took up a job as a salesman for Super Excellent detergent powder.

In 2001, he was in Jodhpur, trying to achieve his sales target with his broken Hindi, when his manager got an urgent call. Navnath had to return home immediately. When he reached their dairy in Pune, he saw a big hoarding announcing the date of the 13th-day ceremony of mourning of his father. He’d died three days prior, leaving behind a debt of Rs 8 lakh.

My feet would hurt, standing from morning till night, but this was our last chance. I kept at it, making litres of tea every day

-Nilesh Yewale, Navnath’s younger brother

The whole family rallied together and pitched in at the Sri Ganesh Amruttulya to save on worker wages. Hoping to increase their income, they tried selling vegetables, milk, tea, and chaat, eventually moving into catering services. Despite their efforts, they were not making much profit and shut the shop.

Looking to pivot, Navnath enrolled in a mobile repairing training course in 2004. He then opened his own mobile repair shop, later expanding into retail. Soon, money started flowing in.

“We were earning Rs 20,000-30,000 in sales per day and we had three outlets. We were suddenly rich,” Navnath said. “But like most first-timers, we made errors. I even started buying a lot of gold jewellery to wear.”

With money being spent faster than it was being earned, coupled with a huge loan to buy a flat, the family found itself drowning in debt again.

“The moment we solved one crisis, another arose, whether someone’s hospitalisation, a new baby, or a wedding,” said Navnath. Their debt ballooned to Rs 1.1 crore, and Navnath couldn’t even afford sweets to celebrate his daughter’s birth.

Finally, at a family meeting in 2011, Navnath decided that it was time to return to what had once helped the family income—selling tea. The business plan was selling only one product and making it big.

“From my experience in multi-level marketing, I realised that the best strategy is to sell something that is a daily consumable good. It keeps bringing customers back. And I thought to myself, what better than chai, which is the beverage people drink the most after water,” said Navnath.

Starting small

To make sure that the 33rd time was the lucky charm, Navnath approached the tea stall with thorough research, attending every free business seminar he could find, finally zeroing in on classes held by the Young Entrepreneur School (YES). He brought his siblings along, and they all learned about marketing, brand building, and managing multiple outlets.

They set clear goals: financial targets, business growth, and social impact. Starting small, they rented a tapri outside Bharati Vidyapeeth.

“We decided on only one type of tea. We did not keep a variety, or even coffee,” said Navnath. His brother, Nilesh, manned the tapri, brewing and selling tea while Navnath kept a diary of customer reactions. He realised that any publicity was good publicity—even complaints that they didn’t offer tea without sugar or coffee helped spread the word.

“My feet would hurt, standing from morning till night, but this was our last chance. I kept at it, making litres of tea every day,” Nilesh recalled. They earned about Rs 3,000 per day and decided to set aside Rs 30,000 for marketing.

The family made thorough use of social media. They invited local leaders to the tapri and then shared the photos they clicked on Facebook and their WhatsApp broadcast list. They even used a cycle with flex boards of the tea shop to roam around the city.

What set the Yewale tea shop apart from the five other nearby stalls was the combination of the authentic tapri experience with strict hygiene. Nilesh wore gloves to prepare and serve tea. As business boomed, they decided to open their first corporate-branded tea shop next to Dagdusheth Ganpati.

“The owner of one of the nearby shops called us crazy because we were selling tea for Rs 10 and the rent was Rs 1.2 lakh,” said Navnath.

But Navnath ignored the naysayers and advised his family to do the same, and there’s been no looking back since then.

Also Read: Vada pavs are up against momos, chole bhature in Delhi. One woman changed the game

The world is their kettle

For the Yewales, the clan comes first. Much like the happy joint families in Sooraj Barjatya films, they spend as much time together as possible, take trips as a unit, and consider each other’s children like their own.

Navnath, as the head of the family and business, hasn’t forgotten the staunch support of his family when he decided to give one last shot to building his dream business.

“My mother used to run a vegetable shop, and another aunt also had a tea shop,” he recounted about that time in his life. His four siblings supported him, either by helping build the brand or by providing for the family through other ventures.

We don’t want to show off. We have learned the hard way that money can come and go at any moment. So, we focus on savings and investments for our future

-Sushama Yewale, Navnath’s wife

Their white three-storey mansion, a few kilometres from their original village home in Askarwadi, Purandhar taluka, houses 23 family members, including Navnath’s mother, uncle and his wife, his siblings, their wives, and children.

Every day begins with a mandatory 7 am aarti, bringing the family together before they set about their respective days.

“We live comfortably but do not indulge in luxury or buy things just to show off that we have money. Even our children are expected to learn the business from the bottom up—making tea, washing utensils, and working at our outlets,” said Nilesh. “They have to build up their own businesses.”

Each of the brothers’ wives receives an equal monthly ‘salary’ to manage household expenses, and family decisions are made collectively during weekly town halls.

“We take trips every few months together. Our last trip was a comprehensive tour of the South,” said Sushama Yewale, Navnath’s wife. Despite their wealth, there are no displays of extravagance in the house, except for a giant flat screen TV and a gilded painting of Shivaji on the battlefield.

In the late afternoon, the wives, dressed in sarees, relax in the drawing room, watching TV or fiddling with their phones before the children return from tuition classes and the husbands come home from work.

Any disagreements are sorted out over cups of tea.

“The tea made at home is different from what we serve in our outlets. We all like to drink ginger tea and have many cups throughout the day,” added Sushama.

As the eldest daughter-in-law, Sushama has witnessed the family’s entire journey of struggle and stood firmly behind her husband.

“My mother-in-law had a pakoda stall. After finishing housework, my sister-in-law and I would help her there,” she said. “We don’t want to show off. We have learned the hard way that money can come and go at any moment. So, we focus on savings and investments for our future.”

They give back to the community through the Yewale Foundation, started during Covid, for various philanthropic activities. Their latest venture is organising job fairs, as reducing unemployment is a crucial goal for both the brand and the foundation.

For the Yewales, business is their lifeblood and their children’s destiny too.

“We love doing business. That’s our hobby too, and we have planned the future ventures of everyone,” said Sushama.

While the children are free to pursue their own paths, they must start independently without tapping into family funds even if they do get an early leg up.

The family’s eldest child, Tanishka, who turns 14 this year, already has a cake and confectionery shop, Tanishka Cakes and Cafe, to her name, managed by Sushama.

The Yewales are always dreaming bigger and bolder. No goal is too outrageous, and no path is too difficult. They’ve survived many odds and the world is their kettle.

“We want the whole world to taste our tea,” Navnath said. “And we plan to achieve that in the next 10 years.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)