Kota: More than 25,000 students in Rajasthan’s coaching hub at Kota put away their textbooks, powered down their laptops, and gathered at a massive ground for a live rock festival. For a few hours on 27 August, they were allowed to forget about topping competitive exams like NEET and JEE, and the loans their parents had taken so that they could become doctors and engineers.

Except Adarsh Raj (18) and Avishkar Kasle (17). They stayed back in their rooms while everyone else danced, cheered and waved their smartphones as a band from Mumbai belted out covers of hits like Kailash Kher’s Allah ke bande hans de (Smile now, god’s child).

At 3:15 pm, Kasle jumped from the building of a coaching institute that he had been attending for the past three years. Four hours later, in another neighbourhood, Raj hanged himself from the window of his rented flat. Both students, on the cusp of adulthood, became No. 22 and No. 23 in official death-by-suicide records at Jawahar Nagar and Kunadi police stations in Kota district.

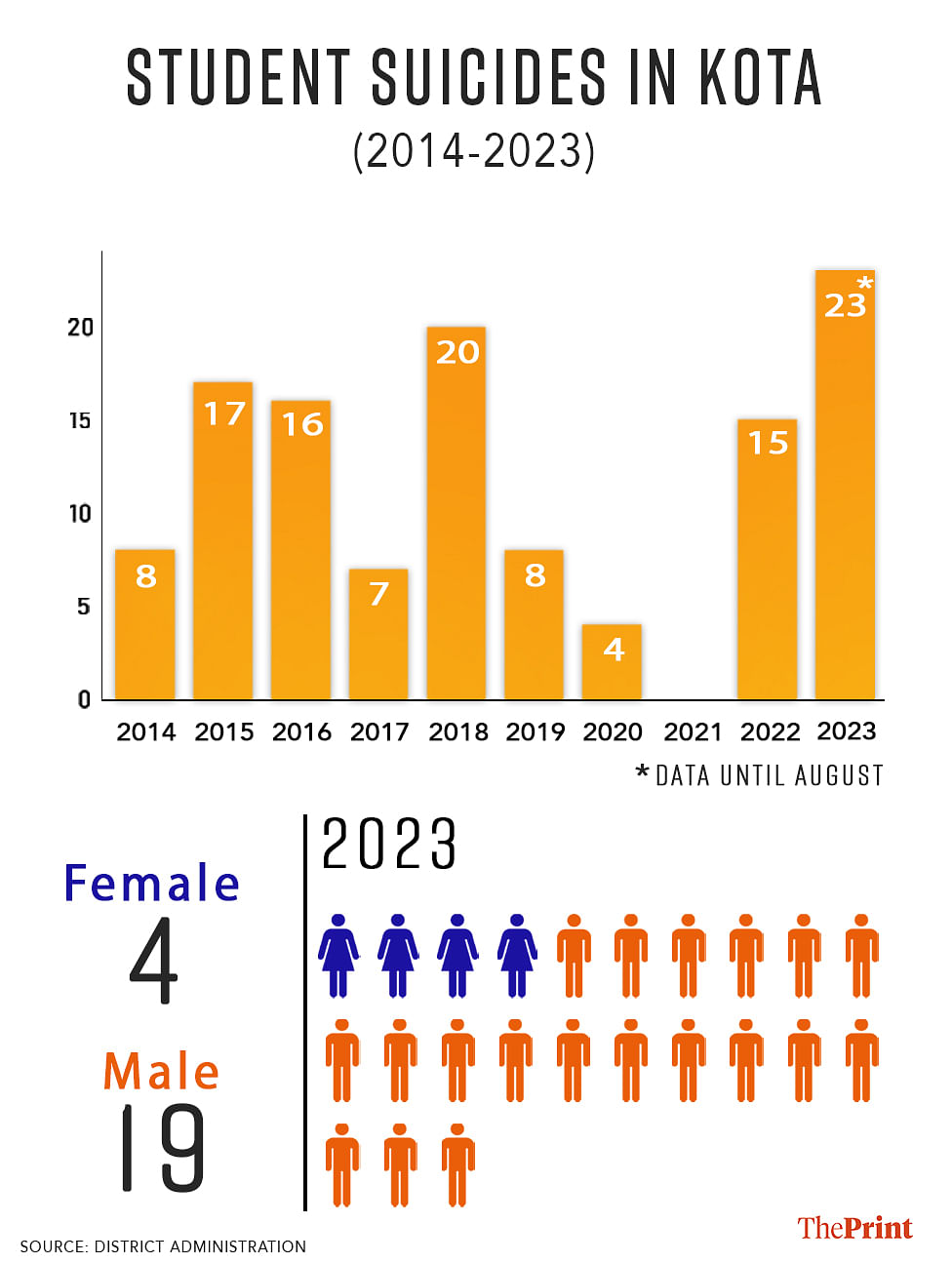

Eight months. Twenty-three students. It’s the highest number of suicide deaths in the three decades since Kota emerged as India’s coaching hub. And the year isn’t over yet, murmur worried teachers.

“It’s as if the children are just landing up in the city and dying,” said Dr Vinod Dariya, professor, psychiatry department, Kota Medical College.

Now, the entire machinery of Kota’s estimated Rs 10,000 crore coaching industry—from politicians, police, district administration, teachers, institute directors, hostel owners, landlords, doctors, counsellors, and psychiatrists—have turned their gaze on the students and their mental health. Kota is now swinging between two extremes—an unsparing treadmill and an over-caring nanny.

“It’s as if the children are just landing up in the city and dying,”

— Dr Vinod Dariya, professor, psychiatry department, Kota Medical College

Students, who were once told that their only job was to study and top competitive examinations, are suddenly being inundated by a slew of measures and questions about their wellbeing. “Why are you not smiling?” “Are you happy?” “Are you getting enough rest?” “Are you eating well?”

“Earlier, we were helping those who screamed for help. Now, we have to find them and help them,” said Om Prakash Bunkar, Kota’s district magistrate. Along with the managing director of one of the top coaching classes, Allen, Bunkar attended the music concert organised by the Kota Hostel Association.

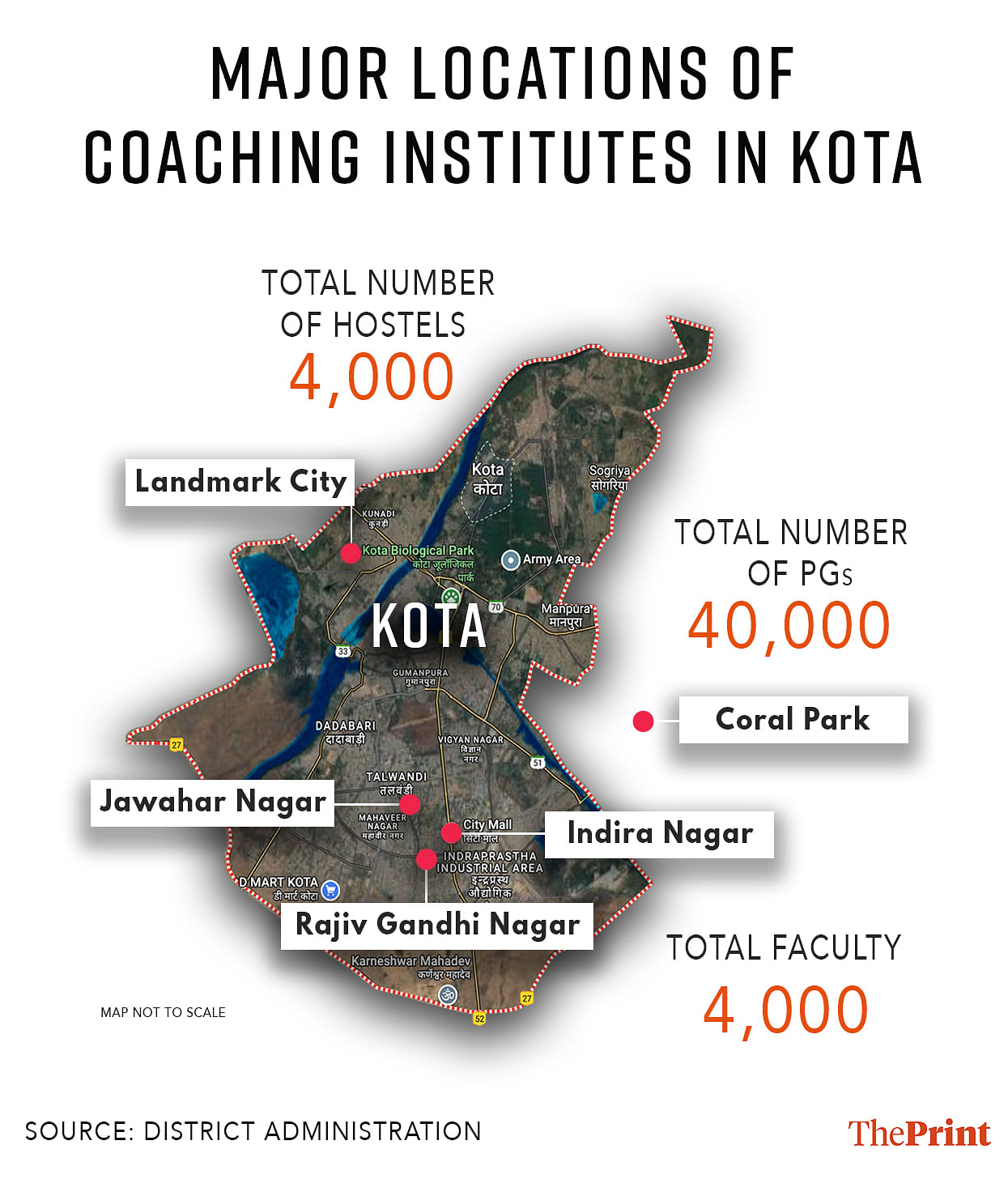

Sundays are Fundays. Counselling sessions, yoga classes, and music festivals are part of the timetable. Tests have been cancelled for two months. Mesh, grilles and bars have been installed on windows of the over 4,000 hostels and 40,000 paying guest accommodations in Indira Nagar, Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, Jawahar Nagar, and Landmark City among other coaching hotspots in Kota. Ceiling fans now have a spring device to function as an ‘anti-suicide’ mechanism. Posters with positive messages jostle for space with class schedules on notice boards. It’s become an election issue yet again.

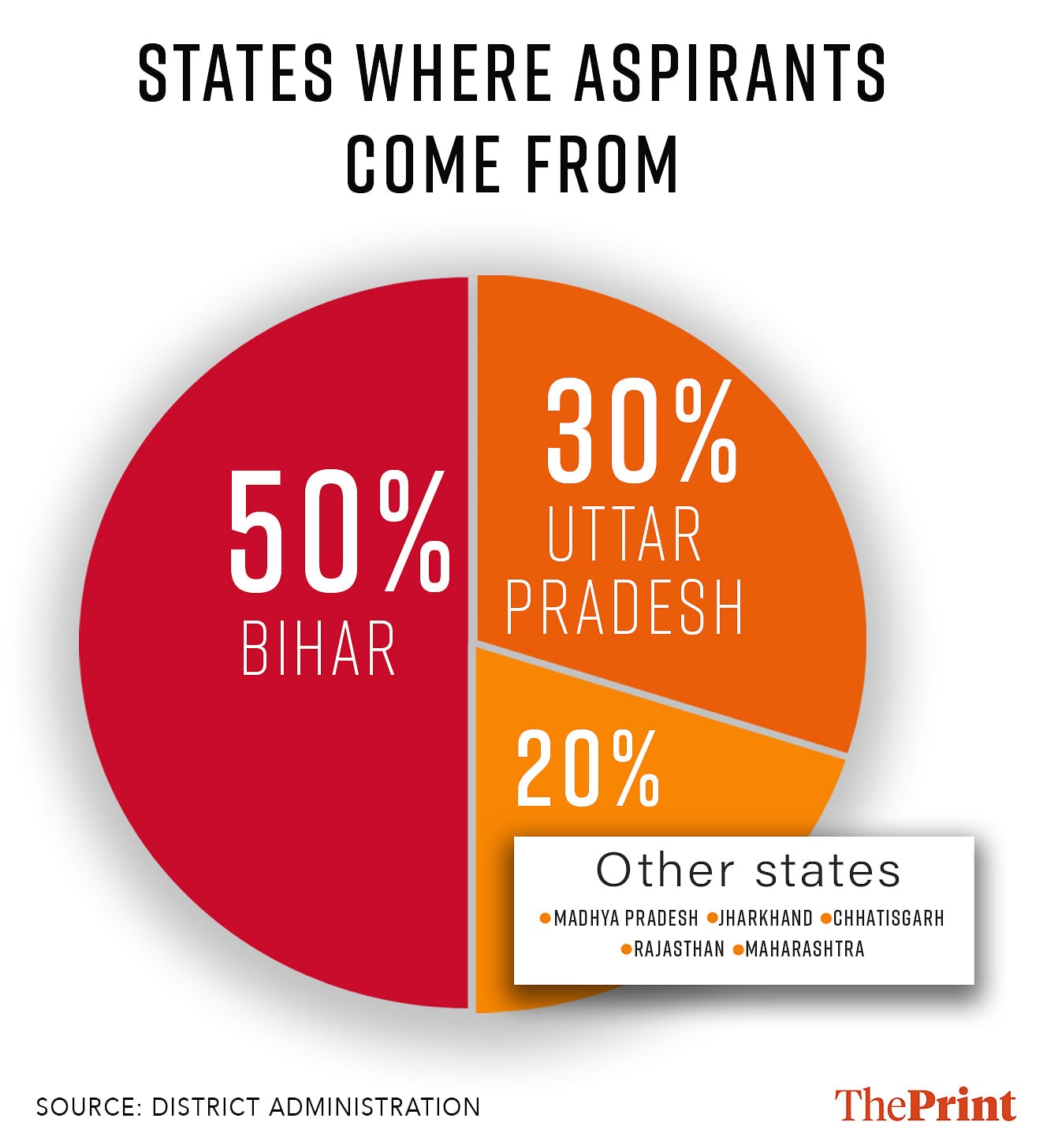

Meanwhile, mothers and grandmothers in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and other parts of India want to leave their homes and set up camps in Kota to keep an eye on their children. The administration led by Bunkar is working on an online portal to identify students vulnerable to suicide. “A list of psychological questionnaires is being prepared,” says Bunkar while emphasising the need to conduct psychological tests on a regular basis.

“Earlier, we were helping those who screamed for help. Now, we have to find them and help them,”

— Om Prakash Bunkar, Kota district magistrate

The helpline rings all the time

On 24 June, Rajasthan’s director general of police (DGP) Umesh Mishra formed a team of 11 officers — six women and five men — to establish a student cell. Most were in their late 40s, and the first thing they did was launch a helpline.

Within a few hours of the helpline going live, SOS calls started coming in. ‘Food quality is worse in our mess,’ reported one caller. ‘My hostel isn’t returning the security fees, I want to go back to my home,’ said another student. One female student was distraught over “vulgar comments” that someone had posted on her social media profile. Another aspirant just wanted to have a long conversation with someone, so ASP Chandrasil Thakur, who was heading the team, spoke to him for hours. “He just said that his heart isn’t in his studies,” Thakur said.

The helpline number has become a single-window option for students. There have been more than 300 SOS calls received on the helpline so far, but five calls shook the entire police student cell.

“These were attempted suicides. Some had locked the door of their room. Another had gone to the river. One person had simply disappeared. We were on our toes working with one counsellor to stop them,” Thakur added. And they did.

The mesh, the grilles, the safety nets, and the spring devices on ceiling fans are not working. Students are just googling new ways, but the helpline is proving to be a success.

Every day since the student cell was formed, ASI Sanju Sharma and head constable Meena put on their blue pants and sky blue shirts—a new dress code introduced for the team—and head towards the hostels, PGs, and coaching institutes. Plainclothes police are now therapists.

They are on a mission to identify vulnerable students.

“Beta [son], please click the photo of this helpline number and post it in your WhatsApp group,” Sharma asked a group of students rushing through the gates of Allen Institute in Jawahar Nagar. This group was a part of nearly 8,000 students in the 2 to 8 pm batch. Some students paused, took a photograph and vanished into the throng of aspirants.

“See, they don’t even have enough time to look at the helpline number launched only for them,” said Meena.

The team then moved to Indra Nagar. The ebb and flow of thousands of students from hostels to coaching institutes and back is a constant in this neighbourhood as well. They come and go in waves, some holding umbrellas to avoid the glare of the sun. Newly constructed buildings emblazoned with rental ads (‘Home Away From Home’), eateries promising home cooked food (‘Maa Ke Hath Jaisa Khana’), tea stalls and stationary shops line the streets.

It’s almost afternoon. Meena and Sharma stop at a boys’ hostel, Matrachhaya. At first, the manager refuses to talk to them. He doesn’t believe they are the police.

“We are not dressed in khaki because we don’t want to intimidate students,” ASI Sharma explains. “Students will not share their feelings with us.” They start arguing loudly until Sharma pulls out her police badge.

Finally, the two policewomen are allowed into the mess. Almost immediately, they are surrounded by students from Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh who have a litany of grouses.

Finally, the two policewomen are allowed into the mess. Almost immediately, they are surrounded by students from Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh who have a litany of grouses.

“The water is full of dirt and they don’t listen to our complaints,” says one group of students almost in unison. Sharma writes down their grievances and promises to do something about it.

As the two women walk towards the stairs, they hear a quiet, tentative “Ma’am.” They turn around to see a visibly nervous student who wants to speak to them on the phone—privately. Numbers are exchanged, and the two officers leave.

They had identified a vulnerable child among 150 boys.

There are times when the police feel out of their depth. There’s this nagging fear that they will miss identifying a vulnerable child, who could end up as ‘No. 24’.

“When students returned in 2022, the suicides returned as well. But this time, the pattern has changed. Previously, the deaths occurred in the winter months [when institutes had completed the syllabus for the NEET and JEE exams]. Now, the deaths are happening in June, July, and August,” — Dr Dariya

Meena will never forget the girl from Gopalganj, Bihar, who called the helpline number a fortnight ago.

“She was hallucinating. She said someone was holding her arms and legs and not letting her sleep. Her hostel manager said she was having nightmares,” said Meena, who went to the hostel and brought the girl with her to the police station. “She wanted to go home.” But the girl’s family didn’t want her to return—it would mean failure.

“Her father said that it was her own choice to go to Kota, and now that he has spent lakhs of rupees on the fees, she should give it a try,” said ASP Thakur, who spoke to the girl’s father. Meena spent the night looking after the girl before the police convinced her family to let her return.

A few days ago, the police found themselves playing mediator between a student who wanted to study English literature and her father who insisted that she become a doctor. “Her father is in the Army, and we had to counsel him because his daughter was under severe pressure,” said Thakur.

The phone never stops ringing.

Also read: What explains the ‘33 student suicides at IITS since 2018’ — academic stress, mental health issues?

Who will counsel the counsellors?

The top brass in Kota—in the police, medical community and district administration—know that the crisis is beyond law and order. What they are offering is a Band-Aid for a gaping wound.

“A team of 11 police officers isn’t enough to deal with 2 lakh students,” said a senior official. And Kota does not have enough clinical psychologists and psychiatrists.

“There are around 20 psychiatrists and five clinical psychologists for the entire district,” Dr Dariya said.

Coaching institutes have hired counsellors after the administration’s intervention. On paper, each centre has at least one student counsellor on its rolls. But there are no checks to determine whether those hired have the relevant credentials and competency to counsel students.

A majority of these counsellors only have a Master’s degree in psychology, said Dr Dariya, who was part of the expert team. Without the necessary experience, they can cause more damage.

According to Dr Dariya, most of the students who died by suicide were NEET aspirants between 16-18 years. It was a similar trend last year as well, when 15 suicide deaths were reported from the district.

Mohini from Ganganagar in Rajasthan was shaken by her interaction with the counsellor at one of the top coaching institutes in Kota.

“My son was feeling low after one of his classmates died by suicide. He used to sit on the bench behind him. And then he was worried about the marks in the test too,” she said. Mohini was so worried about her son’s mental state that she packed her bags and left for Kota to be with him.

“The first question the counsellor threw to my son was, ‘Are you planning to commit suicide?’. The second question was: ‘Have you thought about why you are planning to kill yourself?’” Mohini recalled.

The mother and son never visited the counsellor again, although he is still studying at the same coaching centre.

Aspirants Seema and Krishna, as well as the police, have come to realise that it’s not just students who need counselling; parents do too.

Every time the coaching centres take periodic tests, the marks are sent to two phone numbers. One belongs to the students and the other to the parents.

“This becomes the central point of discussion every third week,” said Beniwal. “The subsequent phone calls with parents turn into guilt sessions.” More often than not, families have taken loans, sold gold and land, or dipped into their savings to pay for their child’s Kota experience. Tuition fees alone range from Rs 1.2-1.5 lakh annually, while hostels and PG rents can cost Rs 12,000-20,000 a month.

“Students know that their parents are struggling to pay. And when their marks dip during the monthly tests, they get more stressed out. They constantly tell their peers that for them, it’s do or die,” said a student.

The Kota administration began collecting data on suicides in 2014 when eight students allegedly died by suicide, said Dr Dariya. The following year, the number rose to 17. In 2016, the police were investigating 16 cases of suicide. Officials realised that many of the attempts were occurring on Sundays when coaching institutes held tests. So they rescheduled the exams for Mondays and declared Sundays as fun days. Under the watchful eyes of parents, the media, and the government, the numbers dropped to seven in 2017. However, in 2018, Kota reported 20 cases of death by suicide. Then the city fell silent during the Covid-induced lockdowns in 2020 and 2021.

“When students returned in 2022, the suicides returned as well. But this time, the pattern has changed. Previously, the deaths occurred in the winter months [when institutes had completed the syllabus for the NEET and JEE exams]. Now, the deaths are happening in June, July, and August,” said Dr Dariya.

Also read: In coaching hub Kota, future job-seekers say unemployment is not Modi govt’s fault

Building a home for parents too

Family members have started taking up residence in Kota to keep an eye on their children. Mothers and grandmothers come with suitcases packed with healthy snacks, spices, and utensils. They rent flats and move in with their children. It’s mostly middle-class parents who can afford to do this.

First, it was the mothers who didn’t have to go to work, then the retired grandparents. And now, working mothers are taking sabbaticals to be with their children, said a police official. Demand for 1BHK flats in Kota is soaring, to the extent that new buildings are being constructed with small and studio apartments.

They take care of their children in the way they know best—by feeding them home-cooked food, removing distractions, and forcing them to study. They watch their children like hawks and are quick to quash any signs of young love or close friendships. This approach, cautioned a police official, can backfire, adding more pressure on the students.

Bunkar recalled an incident where a mother was so upset on seeing her son with a girl that she went to her hostel and publicly shamed her. “The girl later killed herself. Another time, a father and son got into a heated argument. The mother suggested they leave the boy alone for some time, and when they returned, he was dead,” said Bunkar.

There is a pecking order among students in coaching institutes, a strict hierarchy based on performance and marks that determines their life for two years.

Those in the 11th grade are collectively called the nurture batch because they are beginners. When they move to the 12th standard, they are dubbed the enthusiast batch. Then there are the leader (students who need to start their basics) and achiever batches (those who have covered the syllabus at least once.) Alpha achievers are only taught physics and chemistry.

At the top of the pyramid is the star batch or SRG batch— for students who scored above 680 out of 720 in two consecutive monthly tests. They are the brightest and best, those most likely to top the NEET and JEE. “The star batch is offered scholarships. They are handpicked and adored by the faculty. They are the ones whose faces are going to shine on the billboards,” Beniwal said.

In January 2023, the Ashok Gehlot government released the first draft of the Rajasthan Coaching Institute (Regulation) Bill 2023—a promise the Congress had made in its 2018 election manifesto. The draft bill cracks down on coaching classes that glorify success stories of toppers, makes it mandatory for owners to register their institutes, and also suggests holding an aptitude test for admissions. However, nothing concrete has come out of the bill.

Kota is dominated by eight major coaching giants: Allen, Resonance, Motion, Unacademy, Physics Wallah, Career Point, Akash, and Sarvottam. Neighbourhoods like Jawahar Nagar, Indra Nagar, Rajiv Gandhi Nagar, and Landmark City are already heaving with institutes, hostels, and PGs. But demand continues to rise, and the industry has expanded to Coral Park, around 15 kilometres away. A new colony has been constructed to accommodate an additional 10,000 aspirants. Already, two Allen coaching centres have come up next to the hostels.

“Each day, a new student arrives [in Kota]. It will peak in the coming years, and there will be another colony under construction,” said a member of the Kota Hostel Association about the unstoppable sprawl.

For now, government officials have been advising coaching institutes not to put up photos of toppers on giant billboards. But many students are unhappy with this suggestion too.

“Someone has worked hard to be on that billboard. This step would take away the golden opportunity from the topper,” said Mohd Hammad, who arrived in Kota in June from his hometown in Muzaffarpur, Bihar. The billboards with the toppers are a source of inspiration and aspiration for him.

Hammad dreams of the day his face will be painted on that shiny big board with all of Kota at his feet.

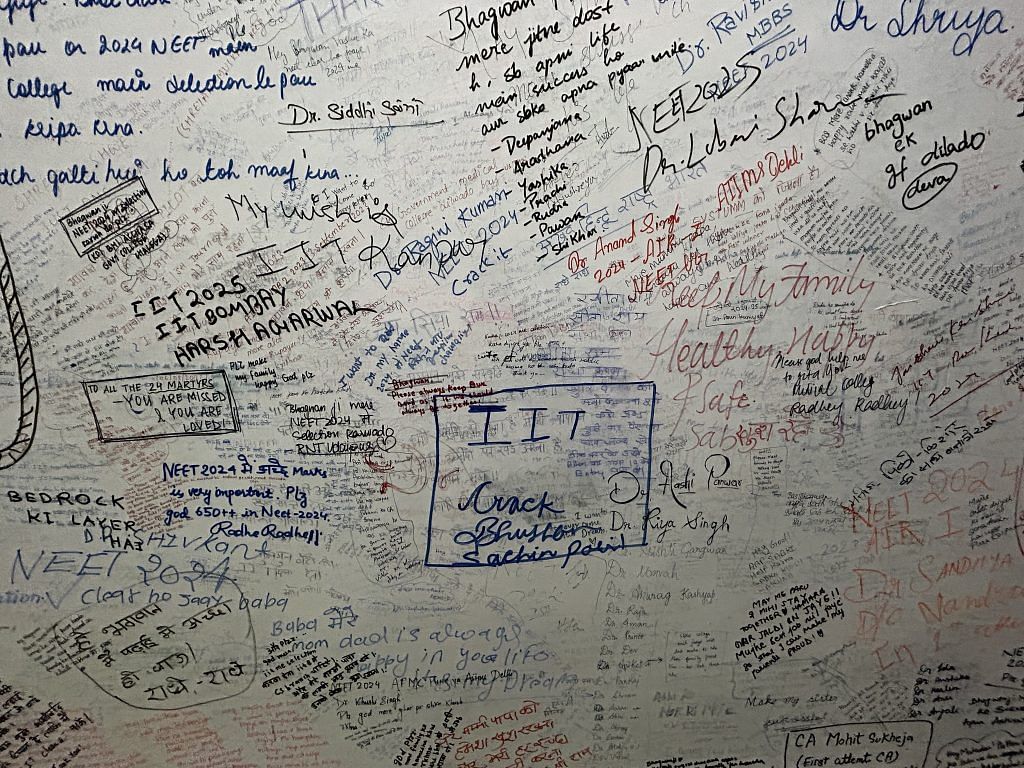

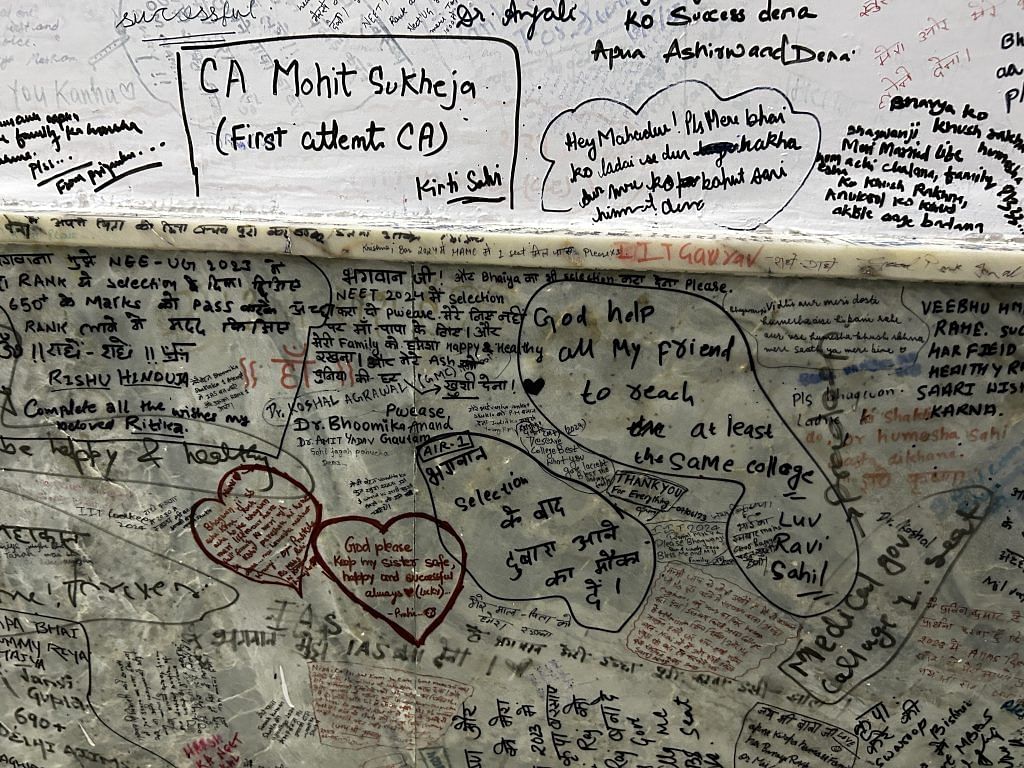

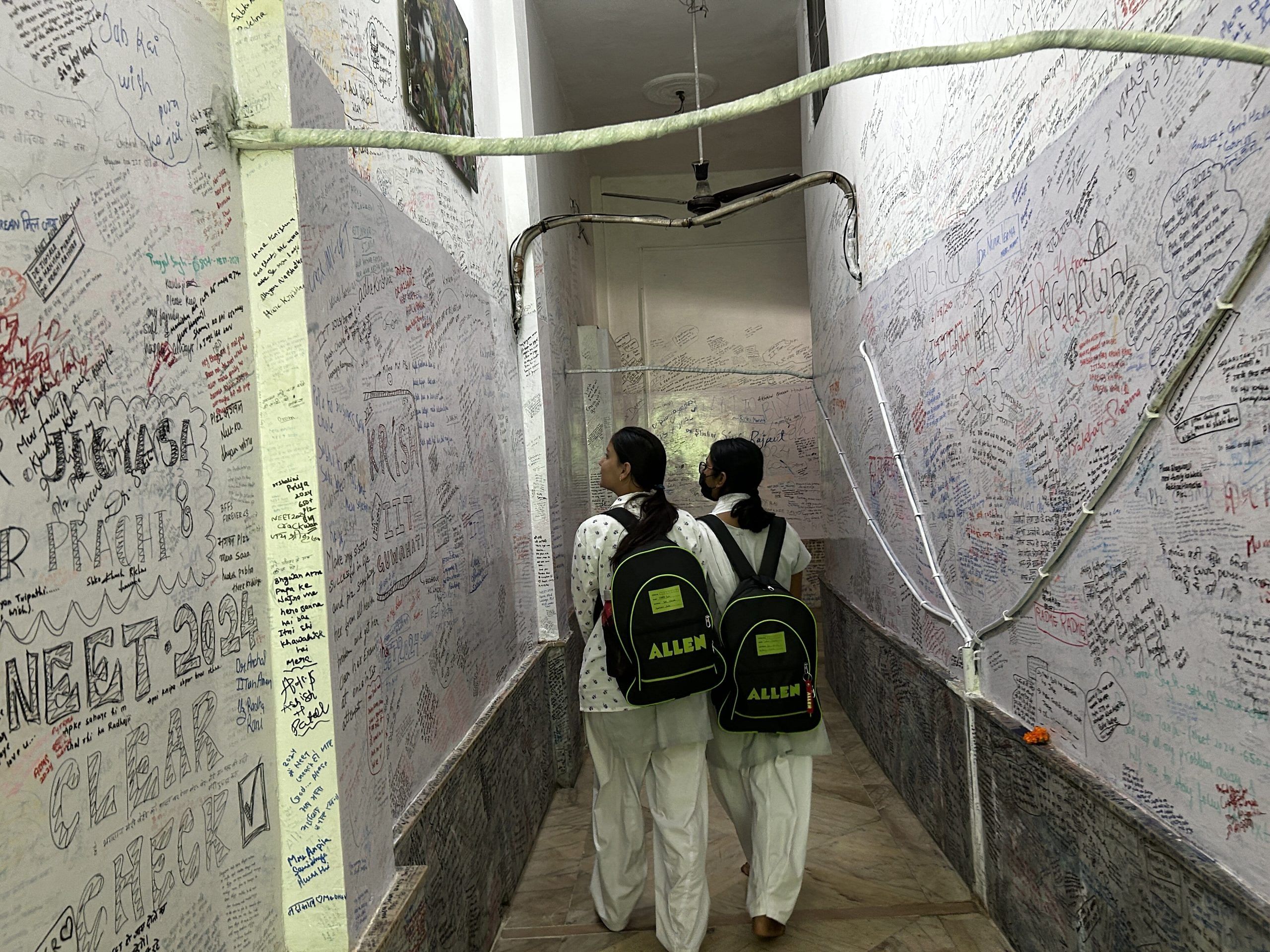

In the heart of Talwandi, a coaching neighbourhood in Kota, the Radha Krishna temple bears witness to the vulnerability and hopes of aspirants and their parents. Its walls are scrawled with thousands upon thousands of prayers and wishes.

“God, you know everything. Please give me the strength to live in Kota and focus on my studies…” reads one. “Please God, guide me on the right path. May I never do anything that can hurt my parents,” says another. “This is my last attempt, God. Please grant me my wish so that I can fulfil my parents’ dream.” The walls are painted over every three months by the temple committee to make space for new wishes.

Ridhi Sharma and Lavni Sharma make it a point to stop at the temple every day after classes. They write their future on the wall with a red sketch pen: “Dr Ridhi and Dr Lavni.”

(Edited by Prashant)