Karnal: Every month two government deposits arrived in 65-year-old Tejpal’s account: the PM Kisan Samman Nidhi and his old-age pension. Then one day last year a new credit of Rs 2,750 showed on his phone. It was a pension not for him but another venerable elder of the household: a mango tree planted by his late mother 78 years ago.

The payment came under Haryana’s Pran Vayu Devta scheme, a one-of-a-kind annual pension for trees above 75 years, launched in 2023 to keep the state’s dwindling giants alive.

“We were happy at our home when the amount was credited. When we applied for the scheme, we didn’t expect that we would get the amount,” recalled Tejpal. The family spent the money on fertiliser and pesticide for the tree. Old but not retired, it still produces fruit that the family sells each summer.

At Tejpal’s village, Pundrak in Karnal, five trees draw a pension — two on private land and three in the Shiva temple premises. The possibility of a pension is now making people think twice before they start eyeing old trees for felling.

“It’s a small initiative with a big goal. People used to cut down old trees and didn’t understand their importance,” said Sunil Harsana, a conservationist in the Aravallis near Faridabad. “The amount is small but the message is big. Now awareness has grown and residents are applying.”

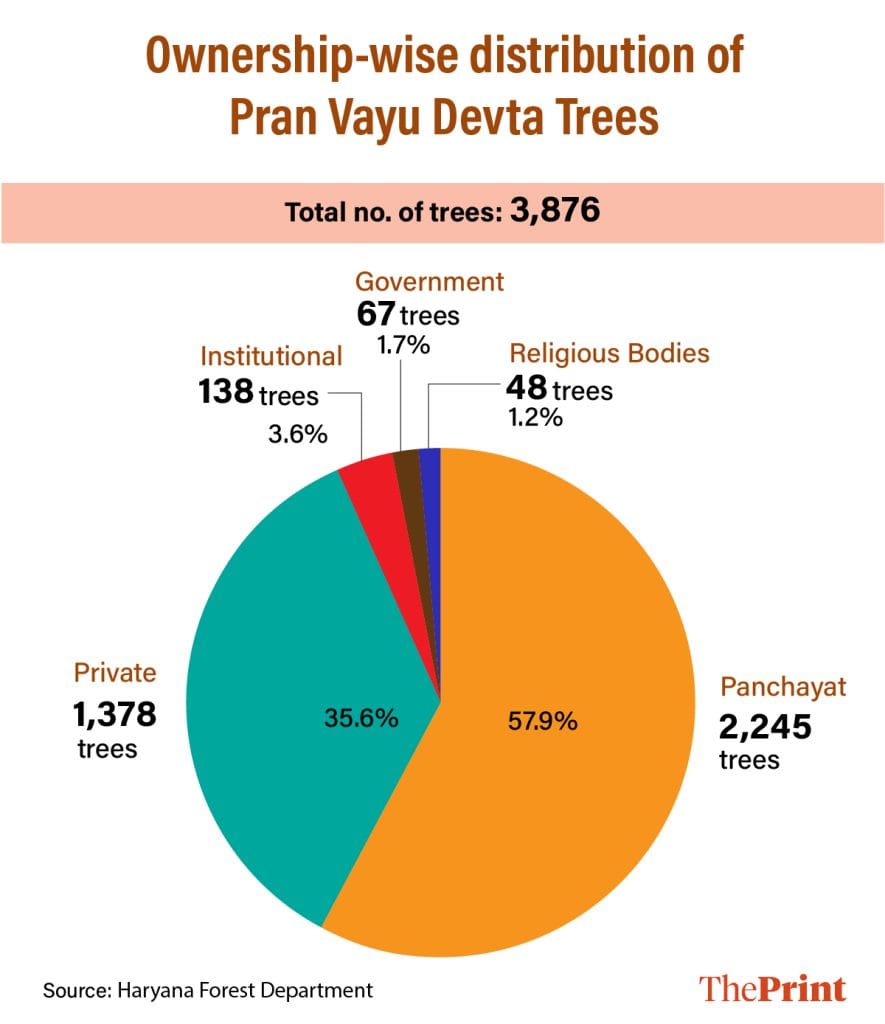

Haryana, the state with India’s lowest green cover, currently disburses a pension for 3,876 trees across 22 districts under the Pran Vayu Devta scheme, with the amount being increased from Rs 2,750 to Rs 3,000 this year. The brainchild of former chief minister Manohar Lal Khattar, it gives custodians an annual grant to care for qualifying trees: aged 75 or more, healthy, and outside forest land. The state government has identified 40 native species with ecological or medicinal value, including mango, neem, peepal, bargad (banyan), pilkhan and kaimb. Fallen, hollow or diseased trees are not eligible.

Most pensioned trees are on panchayat properties, followed by private, institutional, government and religious land.

“Haryana is the first state in the country to implement such a pioneering scheme,” said Khattar during the launch of the scheme in October, 2023. He asked residents with trees of over 75 years to apply for pension by visiting the district forest department. This is what Tejpal’s family did when they heard about the scheme in 2023.

“The scheme helps us to care for our decades-old tree properly,” said Tejpal’s son, 27-year-old Ravi Kumar, sitting on a wooden cot under the sturdy mango tree.

I gave all the details about the tree to the official and gave them my bank account details also. Months have passed but I did not get the pension amount

-Jagdish Singh, Anangpur resident

These old trees are not just silent witnesses to the passage of time, but collectively crucial to mitigating the effects of global warming. Old trees store far more carbon than young ones and their deep root systems reduce erosion and slow down rainwater runoff.

“Unfortunately, the survival of old trees is threatened by urbanisation and development, compounded by the effects of climate change,” said Pankaj Goel, Haryana’s former principal chief conservator of forests.

Environment experts say the scheme is largely symbolic but important in generating ecological awareness. Its guidelines note that logging, land use change and habitat loss are shrinking the population of old trees.

“People have stopped cutting trees in their backyards if they are over 75 and are instead applying for the pension,” said Vipin Kumar, an Indian Forest Service officer in Haryana. With a nudge from the government, villagers now gather around the pensioned trees on World Environment Day, worshipping them with tilak and garlands.

However, hundreds of applications are pending in the forest departments of the state, and so it is likely to remain for the next few years. There is a cap of 4,000 trees until the scheme is reviewed after five years.

Also Read: An IAS officer brought down Lucknow’s garbage mountains. He’s ‘kalyug ka Hanuman’

A long wait

This unique and imaginative scheme is now getting drowned in red tape and delay. In many villages, residents who registered their old trees months ago are still waiting for the pension to arrive.

That is the case even in villages at the foothills of the ecologically sensitive Aravallis, including Anangpur and Mangar Bani in Faridabad district, which has 53 trees covered by the scheme. In June, the district administration called residents for fresh registrations, but even those who signed up earlier have yet to see the money.

Payments were approved for four trees—mango, neem, and peepul—in Mangar Bani earlier this year, but not a single credit of Rs 2,750 has been received.

In Anangpur, forest officials came a year ago to record details of a massive bargad tree at the Badwali Chaupal. The tree’s branches give shade to several houses and there’s always someone smoking a hookah under it.

“I gave all the details about the tree to the official and gave them my bank account details also. Months have passed but I did not get the pension amount,” said Jagdish Singh, a resident of the village that traces its roots to Anang Pal Tomar, the first ruler of Delhi. “This is one of the oldest trees of this area and it deserved the pension.”

Singh claims the tree in question is more than 700 years old. But the only new nod to its importance is a bench installed beneath it by the Municipal Corporation of Faridabad.

Trees with paperwork

Two years ago, Karnal forest officials came to Pundrak to spread word of the scheme. Tejpal applied, and soon they were in his field, inspecting the mango tree, asking questions, and jotting down the details.

“The forest official inspected our mango tree and asked us about how old the tree is, who planted it and also checked the health of the tree,” said Tejpal.

The mango tree received the pension for 2023-24 though this year’s payment has been delayed.

The tree itself, however, has been a reliable source of income for the family for generations. Apart from what he earns in the milk business he runs with his son, Tejpal earns more than Rs 10,000 a year from selling mangoes from the tree, which his mother planted in the immediate aftermath of India’s independence.

The ages of the trees were recorded based on ocular estimates and after enquiry from the senior villagers. The other parameters such as ownership, diameter at the breast height, crown diameter, geo-location, health status were also recorded

-Vipin Kumar, forest service officer

In Karnal, 112 trees are covered under the Pran Vayu Devta scheme, all but one in rural areas. This year officials inspected 54 more and the pensions are in process.

For each tree, the forest department maintains a 21-column proforma, with details of the custodian, location, species, height, crown diameter, health status, ownership, and age. One column lists whether a tree is “economically” or “medicinally” valuable.

Every application is verified by a five-member district committee composed of forest officers, representatives from the deputy commissioner, panchayat bodies, the state biodiversity board, and range officers.

“The ages of the trees were recorded based on ocular estimates and after enquiry from the senior villagers. The other parameters such as ownership, diameter at the breast height, crown diameter, geo-location, health status were also recorded,” said IFS officer Vipin Kumar.

He added that the pension of the trees will be hiked from time to time at rates proportional to the increase in the state’s Old Age Samman Pension.

The state marks each beneficiary tree with a green stone slab listing its species, age, village and the year it was added.

In Pundrak’s Shiva temple stand three old banyans — aged 90, 230, and 290 years. Last year their pensions totalled Rs 8,000, credited to the account of sarpanch Naresh Kumar.

“I gave all the money to the temple. From that amount the trees are being taken care of and money was also invested in temple needs,” he said.

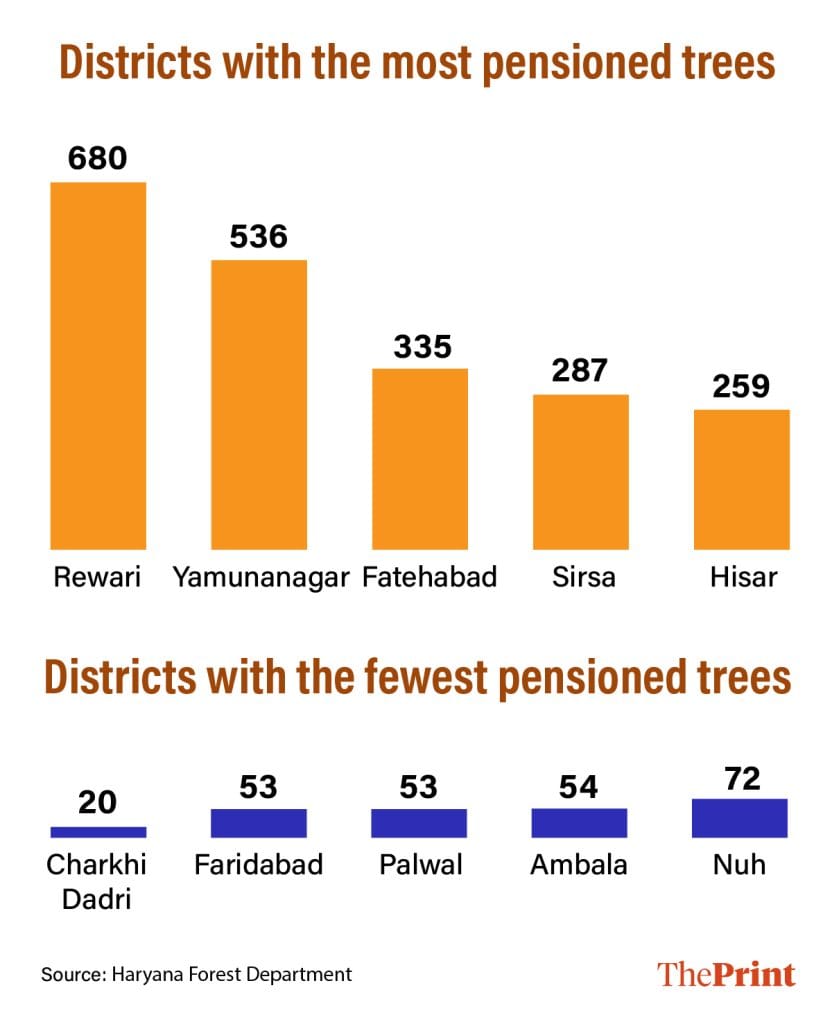

Rewari has the highest number of pensioned trees at 680, followed by Yamunanagar (536), and Fatehabad (335). Officials said no applications have been rejected so far.

The scheme guidelines say it will remain operative for a period of five years, after which a review will be conducted. Until then, the scheme has a limit of 4,000 trees. A senior forest official said Haryana spends about Rs 1 crore annually on the programme.

“Once a tree is under the pension, it is not allowed to be cut or damaged for any construction and development activities without the approval of the committee,” he added.

Also Read: No mafia, just driftwood—Chamba forest dept on ‘floating logs in Ravi’ clips that even reached CJI

‘Gods’ with pensions

Besides being on the government payroll, “pension vale ped” become celebrities once a year, garlanded and worshipped under banners of Pran Vayu Devta, which translates roughly to ‘God of life breath’.

On World Environment Day, the Haryana government organises ceremonies across the state, with forest officers, deputy commissioners, and even the principal chief conservator of forests turning up to offer their respects to the leafy village elders. Ahead of the 5 June celebrations, the forest department even puts up posters at each site, declaring “Vishwa Paryavaran Diwas Pran Vayu Devta.”

Last year, 507 trees were worshipped in Yamunanagar district alone. Residents circled the trees, performed aarti, and decorated them with vermilion tilak. This year in Fatehabad, where 335 trees draw pensions, residents took oaths to plant more trees and save electricity and water.

“Pran Vayu Devta Yojana aims to prevent felling of trees and promote environmental conservation,” said Rao Narbir Singh, Haryana’s wildlife minister at an event in Narnaul.

Former principal chief conservator of forests Pankaj Goel attended one such celebration in Pinjore, Panchkula, last year. He requested people to plant more trees.

“Honouring our Pran Vayu Devta trees through this statewide worship function not only recognises their ecological value but also reinforces our commitment to preserving Haryana’s rich natural heritage for future generations,” he said.

But in Anangpur, villagers are getting impatient for the pension of their beloved 700-year-old-tree, especially in the wake of thunderstorms and incessant rainfall. They are afraid the pension, when it comes, might be too late.

“Everyone in the village knows this tree. Everyone has their childhood stories associated with it and it has been standing in the middle of the village for centuries. It should get a pension as soon as possible,” said resident Gautam Bhadana.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)