Dehradun: Vikas Verma — Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader, Dehradun native, and soft-toy seller in that order — has a bone to pick with the Uttarakhand BJP government. When it comes to the state’s ancient, sacred temples, the government seems to be confusing pilgrimage with tourism.

“Why should people go to Badrinath and Kedarnath on their honeymoon?” thunders Verma, whose loud, assertive voice is replaced by a perfectly modulated tone when he sells pink-and-white teddy bears to children. “Our temples are sacred and should not be treated like tourist spots with hotels and bars. Yes, the state needs to be developed, but why should the government take money from Hindu temples to do so? We do not know where the money will go — and we do not want priests to become servants of the government.”

The BJP is spearheading temple freedom movements in southern states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, but the Pushkar Singh Dhami-led government has taken the opposite route in Uttarakhand, also known as devbhumi (Land of the Gods). Here, tourism is a major economic driver, prompting the government to seek revenue from the state’s famous temples to improve infrastructure. But this has proven to be tricky territory.

A few years ago, the carefully constructed temple-government-priests-devotees balance threatened to come undone, sparking renewed demands for temple freedom from Hindu groups. The state recovered quickly, but it is still struggling to find a perfect model that earns revenue, attracts more visitors, upholds the role and traditions of priests, and keeps temples running like a well-oiled machine.

The BJP state government’s short-lived attempt in 2019 to wrest control over temples from priests through the Char Dham Devasthanam Management Act backfired, forcing its repeal in 2021. The government’s aim was to directly manage temples and utilise their income for developing surrounding areas, but the move was perceived as an attempt to interfere with customary traditions and immediately met with resistance.

The preservation of temple management traditions remains a hot button issue nationwide for Hindu groups that emphasise ‘tradition’ over all else. Their latest ‘victory’ was on 27 February, when the Kerala High Court ruled that only Brahmins can be priests in the Sabarimala temple. Similar traditionalist sentiments are also pervasive among Hindu groups in Uttarakhand.

When the priests came down from the mountains to protest against the Char Dham Act outside Dehradun’s state legislative assembly, Verma was there with them in solidarity. He helped organise dharnas for local priests who feared the government would interfere with their appointments. They didn’t want Uttarakhand to become like Tamil Nadu, where the state government has a grip on temples. The widespread agitation against the Act, which brought 52 temples under state control, proved successful. The BJP government repealed it in 2021, right before being re-elected to power in the 2022 state elections.

Our temples here are historic, remote, and accident-prone — they require a proper management system to create a robust local economy. Who else will do it but the elected government?

-Ajendra Ajay, BJP leader & chairman of the Badrinath Kedarnath Temple Committee

Today, there’s a mixed model for temple administration in Uttarakhand. Some temples, such as Badrinath and Kedarnath, are managed by the 15-member government-appointed Badrinath Kedarnath Temple Committee (BKTC), headed by a BJP leader. Others, such as Gangotri and Yamunotri are run privately by Brahmin communities. In the debate around temple management, this balancing act positions Uttarakhand as the proverbial middle path.

This mixed model grants priests significant control over the temples, including appointments and how rituals are conducted, while the BKTC, with its government-appointed head, handles administrative matters. This differs from models like Vaishno Devi and Tirupati, which also grant significant autonomy to priests but are headed by government representatives—the J&K governor and an Andhra Pradesh MLA respectively.

But even in Uttarakhand, the system is being contested. It’s a work in progress, at best.

In the complex web and tug-of-war over Hindu temple management, the holiest cow is the appointment of priests. Any new intervention is viewed as a threat to age-old traditions.

Also Read: Who should run Hindu temples? Tamil Nadu is the epicentre in new tug-of-war

Mixed model—balance or confusion?

Every year, tens of lakhs of devotees flock to Uttarakhand to traverse its most famous pilgrim circuit, the high-altitude Char Dham Yatra, which covers Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri. But this yatra also represents the temple management divide in Uttarakhand.

While Badrinath and Kedarnath fall under the government-run BKTC thanks to a colonial-era law, Gangotri and Yamunotri are in private hands. This split is not an ideal situation, according to BKTC chairman and BJP member Ajendra Ajay.

“Our temples here are historic, remote, and accident-prone — they require a proper management system to create a robust local economy. Who else will do it but the elected government?” asked Ajay. “In Uttarakhand, temple management is very important for the state’s economic development.”

Leaders in the BJP’s Uttarakhand unit insist that the protesting priests were misinformed. They claim the intention was never to interfere with temple operations, but simply to manage temples’ money better so that the funds could be used to improve facilities for pilgrims and tourists.

Before the Char Dham Act, 47 of the state’s major temples were administered by the BKTC. The contested new law simply added a few more temples, including Gangotri and Yamunotri, to its purview. After its repeal, the BKTC was reinstated in 2022 to oversee arrangements for pilgrims, maintain the Himalayan temples, and improve infrastructure.

The state government is keen for visitors and infrastructure to create a virtuous cycle, but purists fear that sacred sites run the risk of being sullied with the ‘nefarious’ activities of tourists.

A rare political U-turn

In the complex web and tug-of-war over Hindu temple management, the holiest cow is the appointment of priests. Any new intervention is viewed as a threat to age-old traditions held dear by devotees, especially in states like ‘devbhoomi’ Uttarakhand.

That played out dramatically between 2019 and 2021, and fear, furore, and fake information flew fast and thick.

Located high up in the Garhwal Himalayas, the towns of Badrinath and Kedarnath have drawn intrepid Hindu pilgrims for centuries. The pilgrimage is long and arduous, often completed on horseback. Both towns have become symbols for Uttarakhand’s temples, different from the far more accessible temple towns of Rishikesh and Haridwar.

Centuries-old traditions come to life inside these temples, the foundations of which were laid by Vedic ascetic-philosopher Adi Shankaracharya. One such tradition is that both temples have rawals (head priests) from South India—a lineage that has been uninterrupted for over 300 generations. The rawal in Badrinath is traditionally a Namboodiri Brahmin from Kerala, and a Lingayat from Karnataka presides over Kedarnath.

Under them are hereditary Brahmin priests, and hak-hakukdars — those who have traditional rights to perform ceremonies at these temples. Many assumed that it was this rawal and hak-hakukdar system that the Char Dham Devasthanam Management Act was dismantling in 2019.

“What would we do if the leader of the board was a Muslim or a Christian?” demanded Pandit Uday Shankar Bhatt, head priest at a Hanuman temple by Dehradun’s famous clock tower. “A person from any religion can become an IAS officer or a politician. How would we guarantee that they will not destroy our temples?”

But this fear was unfounded. The fact is that the Act carefully mandated that members of the management board should be followers of the Hindu religion, even codifying in law that there should be one “expert in Sanatan Dharma”.

Bhatt was one of the priests who protested against the government’s move, sitting on the frontlines of protests in Dehradun. To him, the fight is between dharampremis — a term he prefers to ‘Brahmin’ — and a government that wants to commercialise sacred spaces.

A person from any religion can become an IAS officer or a politician. How would we guarantee that they will not destroy our temples?

-Pandit Uday Shankar Bhatt, temple priest

But according to the state’s BJP workers, the controversy over the Act and its subsequent repeal were an unfortunate result of poor communication. Rumours and misinformation ran rampant, instilling fear among devotees that the government would try to interfere with the internal matters of temples and the rights of rawals and hakhakukdars. And the biggest anxiety was that the priests would lose their income, and money taken from the temple would be diverted to other areas.

As the state elections approached, the protesting priests formed a Hak Hakookdhari Mahapanchayat Samiti and announced that they would participate in the polls, campaigning against the BJP and fielding their own candidates for 15 Vidhan Sabha seats. It forced the BJP to repeal the Act.

This U-turn is similar to what happened with the central government’s farm laws, say workers in the BJP’s state unit. Just as the massive farmers’ protests forced the central government to back down, agitations by priests just before the 2022 elections pressured the BJP into repealing the law.

The Char Dham Devasthanam Management Act essentially aimed to extend the existing BKTC Act, a colonial-era law from 1939. The idea was to set up a shrine board and streamline the pilgrimage routes to boost the state’s tourism revenue. But irate priests responded by turning then Chief Minister Trivendra Singh Rawat into the target of their discontent. They even displayed black flags to him in Kedarnath when he visited it ahead of Prime Minister Modi’s arrival there in 2022.

“Both acts clearly said that all traditions will be maintained,” said Ajay. “The BKTC only manages the temples. We don’t interfere in the way the temple is run. We are just trying to create and maintain good infrastructure around the temples.”

The BKTC board, headed by the BJP’s Ajendra Ajay, passed its budget for this year on February 24. The budget has gone up by nearly Rs 20 crore to Rs 116 crore, the highest so far in BKTC’s history. And for the first time, the board has earmarked Rs 10 crore for the state government to spend on infrastructure and facilities related to the temples.

Both sides of the aisle in Uttarakhand want to achieve efficiency and infrastructural development. But rumours and misinformation made the process complicated.

The elusive ‘perfect model’

The perfect temple administration model according to both the BJP and the priests inUttarakhand is the Vaishno Devi template —which has achieved a rare and tightrope balancing act between government and priest control.

Introduced by former J&K governor Jagmohan in 1986, the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board is headed by the governor but operates independently otherwise. The Tirupati temple too is governed by a similarly independent board constituted by the Andhra Pradesh government.

Instead of provoking anger, Jagmohan’s takeover was hailed as sorely necessary for Vaishno Devi. The temple, once lacking basic amenities like toilets, drinking water, and accommodation, was transformed into a seamless, modern destination.

The initial objective was to improve pilgrim facilities, including paving roads, constructing water storage tanks, and repairing electricity poles. Subsequently, the government stepped back, and the reins were taken over by the shrine, consisting of civil servants and pujaris and headed by the J&K governor.

Both sides of the aisle in Uttarakhand want to achieve this level of efficiency and infrastructural development. But rumours and misinformation made the process complicated. Unlike Jagmohan’s midnight takeover which he executed with barely a week of governor’s rule left in Kashmir, the Char Dham Devasthanam Management Act simmered for two years as the pandemic set in, and as the VHP kicked up a storm.

With such a commercialised attitude, the sanctity of temples will be eroded. The BJP’s mindset is that these temples are just a source of income, but that runs the danger of being bought over.

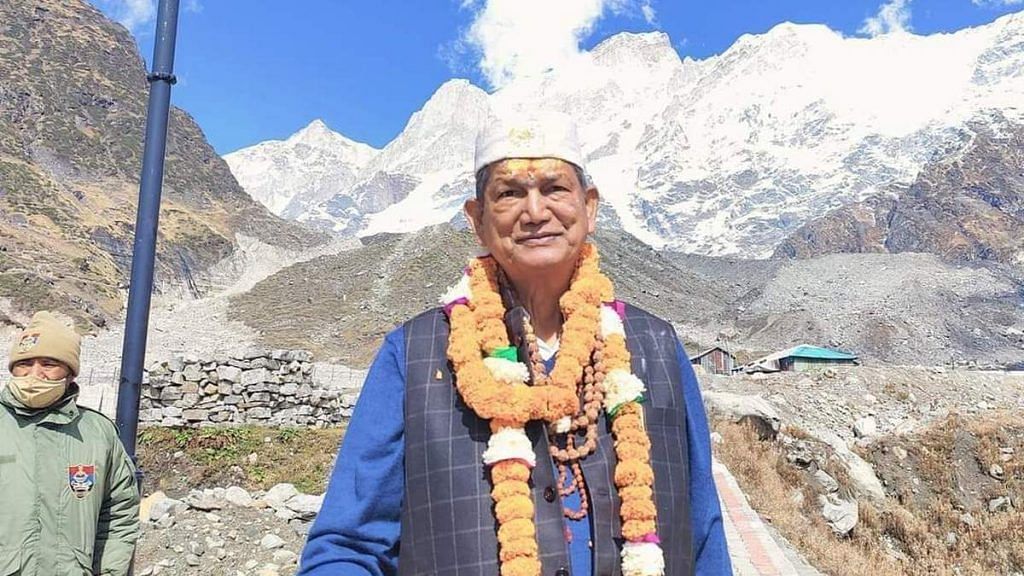

-Harish Rawat, Congress leader & former CM

The VHP was clear in its stance that the government should not be involved in the management of any temples in the state, arguing that Hindu society is best placed to assume this responsibility. They were the wind beneath the wings of the priests, who stood to lose control of their temples. The fear was that non-Brahmins, or worse, non-Hindus, would have a say in how temples in ‘dev bhoomi’ were managed.

Uttarakhand has seen instances of caste-based discrimination within temples. In 2023, the State Commission for Scheduled Castes sent out a letter to all district administrations asking for a list of temples that ban temple entry for Dalits. All 13 districts said no temple in their respective districts does so.

“The government should never do politics in the name of religion,” said Bhatt, who is also a member of the Uttarakhand Vidvat Sabha, an upper-caste group of priests. “They can do other things for SC and OBC welfare—why do they need to make them priests in Hindu temples for this? They can introduce other schemes for Dalit welfare. Temples are places of purity, and priests need to have traditional knowledge, not just book knowledge.”

Also read:

Tourism or pilgrimage?

To the state government, the road to Uttarakhand’s economic development is paved by all visitors — whether pilgrims or tourists.

But others draw a distinction when it comes to temples, arguing that pilgrimage sites cannot be treated like any other tourist destination. Where the state is more concerned with visitors and infrastructure creating a virtuous cycle, purists fear that sacred sites run the risk of being sullied. To them, an influx of tourists to pilgrimage sites means opening the door to drinking, smoking, meat-eating and other ‘nefarious’ activities.

So, when the BJP tried to take control of temples, it was seen as an attempt to commercialise the holy Himalayan hills, according to former Congress chief minister Harish Rawat. It was almost like a self-goal.

“The BJP has been advocating for temple freedom in South India, but here in Uttarakhand they have taken a different stance — to gain income and control mandirs to democratise them,” said Rawat. “All priests identified with the cause and protested against the move, which then became a purely election issue,” he said.

Rawat acknowledged that controlling temples is attractive to any state government because they are lucrative sources of income.

“It’s not like I didn’t want to make use of it — it would have benefitted the state. But I wanted to strengthen tourism through other routes. I believe in least interference with maximum facilities. The government should be there as a facilitator and helping hand when necessary,” said Rawat. “We recognised the customs and didn’t want to tamper with that.”

Rawat’s government came to power right after the devastating 2013 floods in Kedarnath and Badrinath. His government set about improving the infrastructure — with the guidance of the priests, of course. He recounted receiving interest from big industrialists who wanted to put their stamp on both temple towns, but pointedly declined. They were welcome as devotees, not as developers.

“I said no to business and yes to faith,” shrugged Rawat in Dehradun’s afternoon sunshine. “With such a commercialised attitude, the sanctity of temples will be eroded. The BJP’s mindset is that these temples are just a source of income, but that runs the danger of being bought over.”

The conflation of pilgrimage and tourism has tied the government in knots. The state’s temples are delicate ecosystems that require maintenance and huge infrastructural development — after all, trekking up the Himalayas is no easy task. But the state also needs money to do so. The natural balance has been to use investments in tourism to plug the gaps that temple income cannot.

But many don’t appreciate this balancing act. To them, undertaking such a dangerous pilgrimage is a test of faith, and should be rewarded with a darshan at a holy place and not with a picnic or adventure sports. They are not impressed by places like Rishikesh, which unabashedly offers both worship and water sports as its attractions. Purists like Bhatt and Varma shudder at the idea of couples canoodling in Badrinath, or Kedarnath hotels serving cocktails in rooftop bars.

“In the last 35 years, it is our misfortune that the government has not understood the difference between pilgrimage and tourism,” lamented pujari Bhatt.

The irony is that without the government providing accommodation for pilgrims, private hotels will inevitably come up to keep up with the huge flow of visitors.

Also Read: Karnataka bill proposes collection of portion of earnings from temples. ‘Anti-Hindu’, says BJP

Developing the Himalayan temples

Kedarnath has a special place in Prime Minister Modi’s heart, according to the BJP state unit. He’s visited six times in the last ten years — each time with huge fanfare and publicity, following which tourism numbers have skyrocketed. During the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, photos of him meditating in a Kedarnath cave and against snowcapped mountains in Badrinath went viral, and hundreds rushed to recreate them.

Selfies and reels are part and parcel of tourism but not pilgrimage, said Verma, a votary of enforcing stricter rules to ensure to restore a purer form of worship. Most people don’t even adhere to respectful dress codes when visiting temples, he observed, shaking his head. Tourism, to him, is a pleasure activity, while pilgrimage is a serious, devotional undertaking.

But the average devotee doesn’t necessarily draw such sharp distinctions.

Seventeen-year-old NEET student Seema and her friend certainly don’t. On a weekday morning, the two take a break from studying to visit Dehradun’s Tapkeshwar Temple, famous for its location on top of a cave. They pose at various points along the temple, and plan on making a reel out of their day. “We’re just here for fun, it’s nice weather and we thought we might as well pay our respects to God,” smiled Seema.

Every other visitor at the temple also has their phone out, snapping photographs at the many scenic points nearby. And the devotees are not so lost in prayer that they don’t notice infrastructure.

“Badrinath is not well organised. Vaishno Devi is far better, the infrastructure is much nicer and the premises are clean,” said 24-year-old Sarthak Desai, a marketing executive in the tourism industry who has visited Vaishno Devi, Badrinath, and Kedarnath.

The latter two have a long way to go, according to him: the stench of horse manure lingers beyond the temple gates, and facilities are unsanitary with no proper bathrooms. Badrinath’s ashram is almost always fully booked, and so most visitors have to stay in hotels, racking up expenses. Vaishno Devi, on the other hand, offers government-organised accommodation, which though far from the temple is still a considerable convenience for pilgrims.

“I’d say that tourism takes place more than pilgrimage at Badrinath,” said Desai, who himself was part of a tourist group of ten people while visiting it. “A simple example is this: the price of water gets more expensive as you go higher up the trek. It’s Rs 20 at the lowest point and Rs 80-100 at the highest. That’s because the locals there have nothing else to depend on but income from visitors — if pilgrimage was the priority, there wouldn’t be this kind of price differential.”

These are exactly the kinds of concerns that Ajay and the BKTC want to address. But they can’t do so without the money.

“There’s no industry in the mountains — the Char Dham Yatra is the single most important event in this state. Every pilgrimage cycle boosts our economy,” Ajay said.

“The ideal model is the Vaishno Devi model,” he added. “But that has only been possible because of government support. Our BJP government is dedicated to temple welfare — why would our government use temple money for other purposes?”

The conundrum has taken on an urgent dimension with the rising number of tourists visiting the state. Verma mulls over this as he stitches together a soft toy at his shop, right outside the Hanuman Mandir by Dehradun’s clock tower.

“Of course, tourism is good for our development, no one is saying that it’s not. But why target only Hindu temples for money to improve tourism?” he repeated. “This Act came to Uttarakhand because of majboori (desperation). But Hindu samaj is united, and the BJP government always listens to us Hindus.”

This is the second article in a series about the tug-of-war between states and temples over control of wealth and worship. Follow the series on this new temple freedom movement here.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)