Karauli (Rajasthan): Dadanpur is a tinderbox. The women weep, gripping placards demanding justice. The men, in a separate corner, talk fervently among themselves. The entire village in Rajasthan’s Karauli district has gathered under a tarp, up in arms about the alleged rape and murder of an 11-year-old tribal girl who was speech and hearing impaired. Grief has mutated into anger.

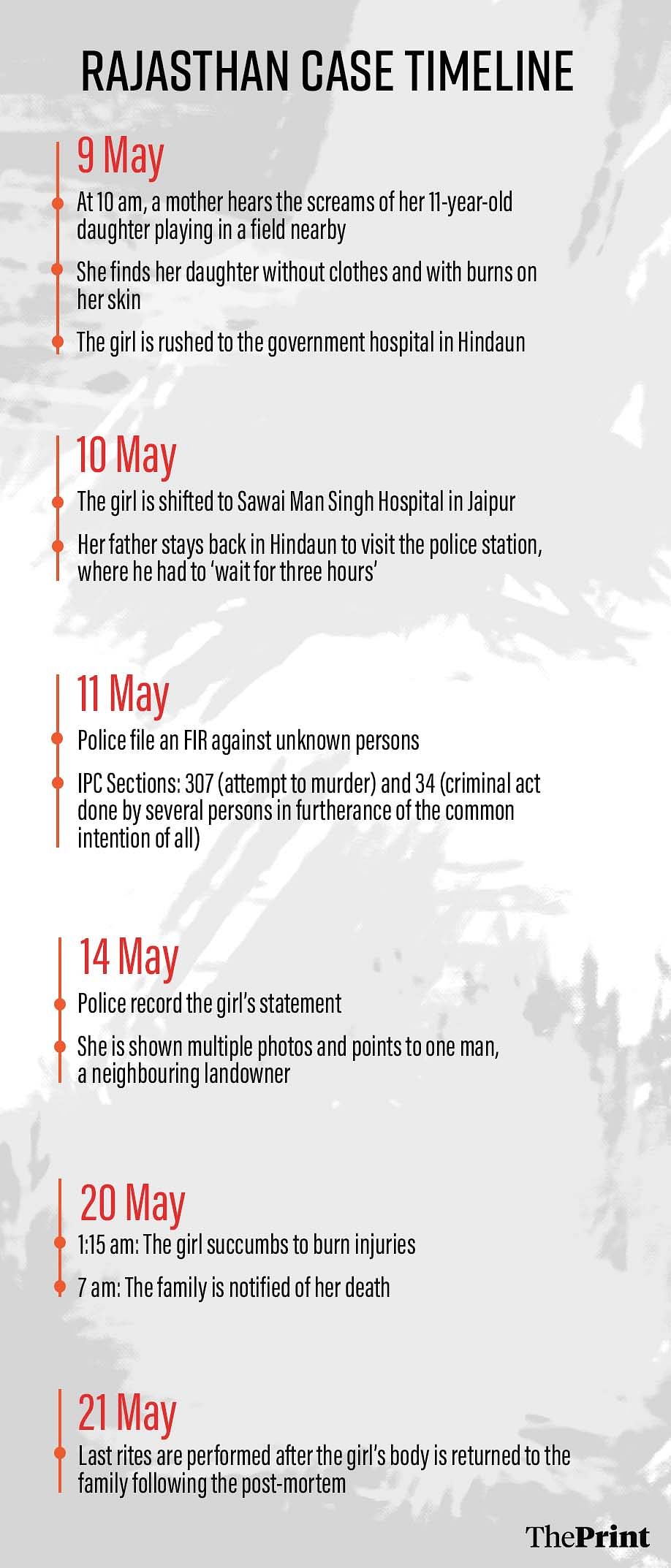

She went out to play on 9 May in a field visible from her parents’ rented home in Hindaun, a town about 35 kilometres from their village. Two men allegedly raped the 11-year-old, doused her in chemicals, and set her on fire. Before she died on Monday (20 May), she identified one of her attackers—a Brahmin landowner from the town.

The system failed her at every level. The police let her down—the FIR was filed two days after the attack, and the man she identified has not been arrested yet. The hospitals failed her as well. Her family was informed of her death seven hours later.

Now, the expected outrage has spread like wildfire. It has galvanised villagers who want the rapists/murderers arrested immediately. It has laid bare the trust deficit between the police, district administration, and villagers.

It was only after she died that a Special Investigation Team (SIT) was formed to probe the case. And Rajasthan’s dismal record when it comes to rape is once again in the news. For the fourth consecutive year, the state recorded the highest number of rape cases in the country—5,399 reported incidents in 2022.

“My daughter was alive. She was eating. We prayed, we called everyone we knew. She could have been saved,” says her father weakly, lying flat on a charpai. He is severely dehydrated and is hooked to an IV. “Just to meet the police superintendent, we had to wait for several hours.”

A nightmare for the family

Up until 17 May, the 11-year-old was cogent enough to identify one of her assailants from the photographs shown to her. He is a resident of Hindaun, owner of the land on which the tribal girl was playing. He runs a shop whose shutters are now down, attached to a pale-yellow bungalow that serves as his home. The 30-year-old man was detained for one night.

“We wouldn’t say he is in police custody per se. But we are calling him in for questioning,” says Karauli police superintendent Brijesh Jyoti Upadhyay. The police have filed an FIR against ‘unknown persons’ under IPC Sections 307 (attempt to murder) and 34 (criminal act done by several persons in furtherance of the common intention of all). It was registered two days after the crime, on 11 May.

For the girl’s family, her silence reverberates through every chant. Villagers in Dadanpur are filled with impassioned rage, while the parents descend into defeat.

The mother sits, surrounded by the women of her village. She seldom deigns to remove her dupatta, but her youngest, a one-year-old boy, is insistent. He nuzzles up to her, and she allows him to come under her self-contained sea of yellow.

“I didn’t see what happened. All I could see was my daughter. All I could hear were her screams. She was trying to tell me. I made her come in and lie down. Her clothes were completely shredded. Then, through gestures, she told me what happened,” she explains tonelessly.

She was naked––which is why the family suspected she had been raped. Everything was in smithereens. Only her slippers were left intact. Her mother found them near a tree.

What followed was a nightmare of hospital visits, delays and rounds of blame game with no arrests so far.

Her parents took her almost immediately to the government hospital in Hindaun, where her condition was declared too serious to treat—she needed to be taken to the government-run Sawai Man Singh Hospital in Jaipur. Her uncle accompanied her on 10 May, while the father went to the local New Mandi police station in Hindaun to report the crime.

The police’s attitude was lax, he claims, and they were dismissive of him.

“I had to wait for three hours to meet the SP. We tried extremely hard to get them to record her statement. We kept calling them. Finally, they came,” he says. Though the FIR was finally filed, the girl’s version of events the were recorded five days after the incident, on 14 May.

Here, too, the versions differ. While the girl’s family says she was lucid and could have recorded her statement, the police claim she was in no state to do so.

She identified the accused—but did not explicitly say he had raped her. “She categorically clarified there was no sexual assault,” says Upadhyay, the SP. Her statement was taken by way of sign language. Upadhyay reiterates that there’s “no conclusive evidence” against the man she identified, which is why the investigation is continuing, and he hasn’t been arrested.

“If the police suspect sexual assault, then a sample is given by the forensics team to the police. Our opinion is based on the forensic science lab. But the report hasn’t come. We are waiting. Its arrival depends on the police investigating officer,” says Dr Kiran, medical jurist, senior demonstrator, Sawai Man Singh Hospital.

The silence from the police has villagers on edge, with calls for the death penalty growing louder.

“He needs to be hanged; it’s the only way. This should never happen to another one of our daughters,” says a paternal aunt.

A ‘hostile’ police force

In a room inside the New Mandi police station, the picture is radically different. The police are on the defensive, dismissing the family’s allegations.

Soon after the incident took place, when what was left of her skin was raw, and the lower part of her body aflame, the girl conveyed to her mother that there were two attackers. But after taking her statement, the police have concluded there was only one man.

“Their aim is different; they want support from the government,” accuses a senior police officer who did not want to be named. Some local newspapers reported that the family was demanding Rs 50 lakh and a government job as compensation. “They are the ones who took a long time. She wasn’t fit for the statement,” the officer claimed.

The family vehemently denies such claims. “I have lost a daughter; will I ask for money from the government? We don’t want a single rupee, only justice,” the father was quoted as saying by The Indian Express.

Beyond the support in Dadanpur, conspiracy theories reign supreme—even at the police station. Many of them are accusing the tribal family of “manufacturing” the case to collect compensation.

The distraught family is aghast at the accusation. “We are poor people. But we don’t want any money. We just want justice for our child,” declares an aunt.

The child’s mother cannot read or write, while the father has studied till Class 12. But they wanted their daughter to get an education. In fact, she was spending her summer vacation with her parents in Hindaun. Otherwise, she would have been away—at a government school in Karauli district for differently-abled children.

They make their living by selling milk from their two buffaloes. Navigating the legal and medical system seemed insurmountable from the very start.

“I did not and could not speak to any policemen. I didn’t know what medicine the doctors were giving my child, what her treatment entailed. I also have three other children to take care of,” her mother whispers. She is wearing a tiny silver nose pin. She is reminded of her daughter’s fixation with nose rings. She wanted a new one every single day.

Both parents frequently burst into tears—the father loudly, the mother in muted tones. They are mourning their daughter, but it is accompanied by a litany of unanswered questions.

“Why aren’t they telling us what is in the post-mortem report? Why can’t we see her statement? When will we go to court? Why are we being kept in the dark?” the father asks.

‘Intelligent, adored, selfie-taker’

He pulls out his phone and scrolls through the camera roll. His daughter was an obsessive selfie-taker, and his phone is littered with pictures of her at various angles.

“She used to take my phone and click 20 pictures in one go,” he smiles. “There were so many that now I have to delete them.”

According to the parents and other family members, the 11-year-old was “highly intelligent”. Despite being unable to speak, she was an effective communicator, and was adored by her family.

“Everyone wants a son. But for us, our daughter was more than enough. She was better than any boy,” says her grandmother.

After 17 May, a week since her admission at the Jaipur hospital, her condition began to deteriorate. Her head was always spinning, and she was in constant pain. Around 65 per cent of her body was covered in burns. Her mother remembers the soles of her feet—because they were unmarred. Her body was covered in bandages. There was very little skin left.

“There was nothing. Everything had come off,” says her uncle.

Treatment typically entails dressing, antibiotics, and debridement of the wounds. But beyond a point, there is nothing more that the doctors could do.

“When there is this kind of damage to the body, the chances of survival aren’t very high. For a child her age, there was only about a 20 per cent chance of survival,” says Dr Ravi, a junior resident in the hospital’s burn ward.

She died at 1:15 am on Tuesday. The family was informed at 7 am. The last rites and cremation took place at their home—Dadanpur village in Karauli district.

Her last set of holidays was during Diwali. Her father had taken her to a doctor then, who had told him that eventually, she could get surgery, and parts of her hearing could be restored. They just needed to wait.

But her disability was never a hurdle that they needed to overcome. “It was never difficult. We knew everything about her. She told us everything,” he says.

‘We are Brahmins’

In between narrow, winding lanes of Hindaun—populated mostly by lazing buffaloes—is the family’s rented home. There are two small rooms that have been painted a bilious blue, and the contents inside include a television, two charpais, and a makeshift kitchen, distinguished as such by the utensils.

The father makes between Rs 10,000-12,000 a month. From this, he feeds his family of five and also sets a sum aside for his brother and his wife.

A ten-minute drive away, on a wide road in Krishna Marg, is the bungalow of the Brahmin man the girl identified before her death. This family owns about three acres of land in Hindaun.

The suspect, whose name has not been released by the police, is about 30 years old and a father of three—two daughters and a son. According to his wife, he spends all his time at the store. When in need of respite, he does bhajan kirtan at their neighbourhood temple.

“I know he is innocent. I want the truth to come out quickly. Our children are extremely tense and crying all the time. Now, my husband doesn’t do anything the entire day,” says the accused’s wife, speaking to ThePrint outside their home. Curious children from the colony gather around her, holding on to her saree.

Krishna Marg appears to be as close-knit a community as Dadanpur village, with neighbours eager and swift to jump to the man’s defence—and to vouch for his character.

“I haven’t seen such an innocent, straightforward man in my life. And now he is being questioned by the police. The [girl’s] family is trying to make this a political matter. How can they make a target of such a poor, honest man?” says his immediate neighbour.

“All he does is go to the temple. We’re Brahmins, you know.”

(Edited by Prashant)