Bengaluru: Much of writer Anjum Hasan’s life has transpired in North Bengaluru. She has seen the city that was—one that existed before the airport ‘upheaval’. “In a way, I know Bangalore well; in a way, I don’t,” says Hasan, author of books that have shaped the city in modern imagination.

She is witness to the change—seen the explosion of “metropolitan ambition” and “easy money,” and observed the dregs of resistance. Her books look at the contours of life, largely through an urban prism of aspiration, love, art, and movement.

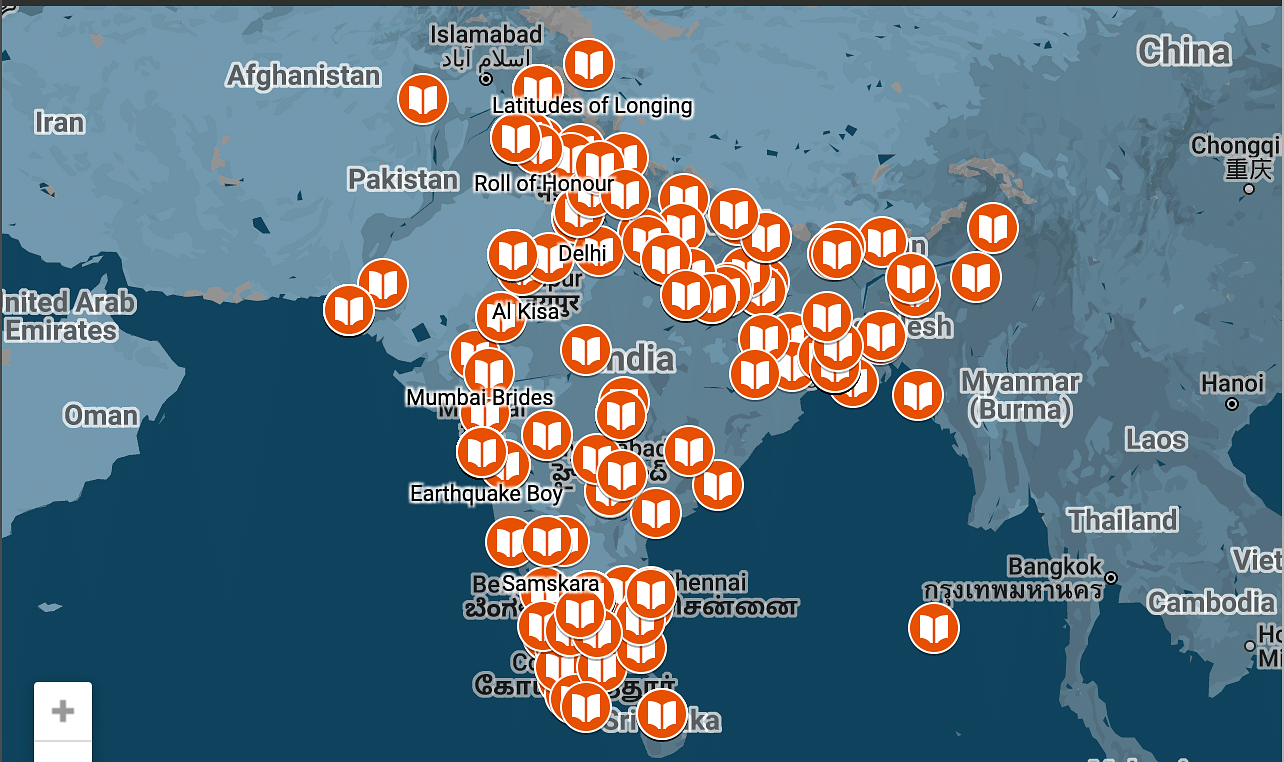

Now, her novels find a mention on a digital map. Literally. An ambitious, newly created public archive called ‘Cities in Fiction’ is taking shape. Readers are locating their favourite novels in Bengaluru, Mumbai, Patna, Chennai, Kozhikode, and more. Founded by scholar Divya Ravindranath and her colleague, writer-editor Apoorva Saini, the database throws the world of fiction open even to those who don’t typically read novels. Locating them within the cityscape, they are reconfiguring how fiction is viewed—welding memory, history, and literary imagination.

At a time when India is urbanising at an unprecedented speed, a new wave of city pride and storytelling is showing up in popular culture. The village has more or less disappeared from Indian literary memory. More books, films and TV series are throwing up city names.

Certain cities ‘belong’ to writers. There’s Rohinton Mistry’s rendering of Mumbai, Kolkata as written by Amitav Ghosh, Mohsin Hamid’s Lahore, Saadat Hasan Manto brought the seedy underbelly of both Lahore and Mumbai to the mainstream, and through Salman Rushdie’s “imaginary homeland”, the city grew less literal and more liminal.

“I find fiction to be a great way to understand cities. It’s a beautiful way to allow affect and emotion into the classroom,” says Ravindranath, a professor and researcher who focuses on urban health, gender, and labour. The repository of novels connects the geographic and the emotional, combining people and place, she added.

Also Read: Indian LGBTQ+ fiction is out of the ‘cupboard’. With a non-elitist, non-Western language

Discovering patterns

The stories have always been there, tucked away in bookstores, glaringly visible on Amazon, or cocooned in libraries. But until ‘Cities in Fiction’, which came along in September 2023, it was difficult to pluck Indian novels out of literary spaces and curriculums and place them in the big bad world.

“We want to open up fiction for people from all disciplines,” says Saini. “What happens when a medical student interacts with fiction?” It’s a tool that can be woven into a number of fields—urban studies, environment, climate, economics, health.

Ravindranath, a compulsive reader of fiction and a researcher of urban spaces, naturally found the point where both her worlds coalesced. She teaches a course at Bengaluru’s International Institute for Human Settlements on the limitations of healthcare systems. The data is all there, but she still turns to a short story, Nagaram (City), by S Rangarajan, better known as Sujatha, translated from Tamil into English, to get her point across. The tale of a mother and daughter, forced to confront how daunting a hospital can be, takes the lecture beyond numbers. They are confused by the various departments and the peculiarities that form the hospital experience. Then, the mother loses her daughter.

“Of course, I could tell you about how people find it difficult to access health systems through data, and I must. That’s my job,” says Ravindranath. “But I could also give you a short story.”

Up until now, there have been no archives of fiction targeted at the South Asian context. Cities in Fiction is the first of its kind. There’s a database that suggests New York metropolis is the most written about; it also assesses different cities through genre.

Cities in literature are record-keepers of major demographic shifts, cultural, political and archaeological changes, urban planning, landscaping, ecology, and almost all aspects of life. In reality, a space/place is always in flux, for our world is constantly being changed or re-arranged

– Description on the archive’s website

There are currently about 350 books mapped by Ravindranath and Saini, and it’s still under construction—initially limited to books by Indian authors written in English and set in metropolitan cities, it now includes books based in small towns, villages, and written in regional languages, including Bengali and Malayalam. Eventually, the archive has expanded beyond India to include narratives from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka as well.

Cities have been created and recreated by authors. The post-Emergency Bombay in Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance is different from Kiran Nagarkar’s bawdy interrogation of the city’s chawl life in Ravan and Eddie.

Ravindranath recalls reading Amitav Ghosh’s Shadow Lines in college and being entranced by Kolkata, a city she had never visited. The book spans different geographies, but Kolkata, mediated by a tea-drinking, cigarette-smoking protagonist, holding forth at ‘addas’ unique to the city and its urban language, is what stuck.

Shadow Lines is a regular fixture in Indian college curriculums, typically found in Postcolonial literature courses, or occasionally under Partition literature. But there aren’t too many courses that look exclusively at how cities are interrogated in fiction, and how they contribute to larger discourse.

“Cities in literature are record-keepers of major demographic shifts, cultural, political and archaeological changes, urban planning, landscaping, ecology, and almost all aspects of life. In reality, a space/place is always in flux, for our world is constantly being changed or re-arranged,” reads the description on the archive’s website, an explanation of sorts for why it has come into being.

It’s also an exciting prospect for readers, to be able to discover patterns and different categories of books by way of the database.

“I for one would love to know all novels written by writers from Western UP, or novels set in Western UP,” says Tanuj Solanki, author of Diwali in Muzaffarnagar and founder-editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine.

Also Read: Climate fiction is growing, but it’s waiting for a Chetan Bhagat

Fiction as a method

Ravindranath and Saini aren’t equating fiction with reality, or saying it should be looked at as a point-blank historical source. Instead, they’re propagating the use of fiction as a method —a lens through which a variety of subjects can be looked at.

For one, Mumbai is notorious for its housing crisis. It’s a city that has been propelled upwards, forcing its inhabitants into cramped spaces with palpable disparities and looming threat of climate change. It’s a many-headed demon, and “there are so many books I can think of that deal with housing in Mumbai,” says Ravidranath.

Amrita Mahale’s Milk Teeth delves into the city’s rent regulation act. Indian-Canadian writer Rohinton Mistry has put Mumbai on display multiple times – particularly, according to Ravindranath, through his 2002 novel Family Matters. It traverses the city in a number of ways. It showcases two versions of housing: one building embodies decrepit grandeur and the other is an example of modest living. It delivers Mumbai to those who are completely unfamiliar with the city and its issues of housing.

“We use this term called fiction as a method. It allows you to look at the same questions, but through the purview of imagination,” says Saini. “Fiction doesn’t come out of thin air. It’s contextualised. It emerges from the world we live in, from the people we live with. There’s space for alternative truths and multiple perspectives.”

A decade ago, Pulitzer Prize winner and arguably one of the most well-known Indian-origin writers Jhumpa Lahiri wrote The Lowland, a novel which deals closely with Kolkata and the reverberations of the Naxalbari Movement. It was criticised heavily by Indian researchers and academics— dismissed as an “anglophone” novel for which the movement is ornamental, used by Lahiri “without any engagement or exploration.”

The Lowland is a part of the database, categorised under “History of West Bengal, Siblings, Family.” It’s an open-source database, sort of a Wiki model, to which anyone can contribute by inserting the details of a particular work into an excel sheet. Saini and Ravidranath take on the role of moderators, not enforcers. Thematic entries aren’t edited at all, since there can be a number of takes on which text encompasses what.

While Lahiri’s novel might not be the most ‘accurate’ representation of the movement, according to Ravindranath, that doesn’t mean it lacks value. “Lindsay Pereira’s book God’s and Ends, that’s set in one Christian neighbourhood,” she adds, giving another example. It provides insight into a particular community, but there remains value in “holding on to those quirks.”

Fiction doesn’t come out of thin air. It’s contextualised. It emerges from the world we live in, from the people we live with. There’s space for alternative truths and multiple perspectives.

– Apoorva Saini, co-founder, Cities in Fiction

Saini and Ravidranath are primarily English readers, and the original database consisted solely of work they were familiar with. But the popularity of ‘Cities in Fiction’ has mushroomed because of social media and the duo is inundated with advice, requests, and contributions.

A post on X opened the floodgates – and through fellow readers and researchers, ‘Cities in Fiction’ expanded its borders.

This flexibility and inclusivity are also hugely beneficial to the classroom space – which has a diversity of characters, many of whom come from dramatically different backgrounds. It’s important for them to feel represented. According to Saini, fiction, short stories and poetry have the power to accommodate students, to make them feel seen. If fiction is introduced on a pedagogical level, it can make curriculums more dynamic, inclusive, and experimental,” she says.

There’s still a chasm that exists between cities and small towns and another between small towns and villages. In cities, people typically live more isolated lives, whereas in small towns, they’re more sandwiched together. This idea of community takes on a larger intensity when it comes to villages—where no decision appears to be singular, and the village as an entity looms large.

Also Read: Is the novel dying in India? Publishers chasing more and more non-fiction

Marriage of memory and history

In 2017, The New York Times published Footsteps: From Ferrante’s Naples to Hammett’s San Francisco, Literary Pilgrimages Around the World, a collection of essays on discovering ‘iconic’ cities that exist in both actual and phantom form. Each essay is an exercise in chasing an image created by a fiction writer or poet, even as the actual cityscape remains solid.

To write about Bangalore is to write about the city’s frenetic instability, the feeling that everyone is cruising on this bulldozing change. But I also want to resist the idea that it’s all fait accompli, try and account somehow for what happened

– Anjum Hasan, author

The city that makes it onto the page is almost always a mirage, a marriage of memory and history. Writers themselves are grappling with their inventions, situated between the real, the imagined and the passage of time.

“Bangalore can be hard for anyone to grasp because it doesn’t have a centre, it’s an agglomeration reaching ever outwards. [Ramachandra] Guha once said it’s a hard city to live in physically but very stimulating intellectually and culturally, and that’s still true,” says Hasan, referring to the city that is her home. “Lots of creative people, civic-minded people, plenty of excellent institutions. But painful traffic, narrow roads, mishmash architecture.”

She has represented the city time and time again, but it’s always a work in progress. There are no absolutes, no singular images.

“Now I want to write about this terminal feeling the city can stir up in me, the panic that there is so much going on here but how long can it last?” she says, referring to Bengaluru’s rapid expansion beyond its pre-ordained borders—both literally and metaphorically.

Bengaluru is also the city where Solanki receives the maximum submissions for a literary magazine named after Mumbai. While there is no way to confirm this observation, he refers to a “concentration of a young and educated population”, more attuned to the idea of literary magazines as publishing routes. Bengaluru’s present avatar has also been shaped by its wave of migrants and the various ways in which it has had to change to accommodate them.

“So to write about Bangalore is to write about the city’s frenetic instability, the feeling that everyone is cruising on this bulldozing change. But I also want to resist the idea that it’s all fait accompli, try and account somehow for what happened,” says Hasan.

Fiction writers are masters at chronicling contradictory worlds, particularly when they exist in the same space. The Indian cityscape is a hotbed of contradictions, and to contend with its magnitude is no mean feat. For Ravindranath, while the form comes with exigencies that prevent it from being ‘historical’, the archival value is immense.

Cities in Fiction is still a fledgling archive. There’s a rich history of literary tradition that needs to be put down, and Saini and Ravindranath—who still have full-time jobs—have made it their weekend project.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)