New Delhi: At Mumbai’s Soho House, a drag artist cosplayed as a librarian to host a children’s tea party. From head to toe in shades of pink and white, the librarian read from the book, The Many Colours of Anshu by Anshumaan Sathe. A small group of children hung on to every word, curious about the seven-year-old who did not want to be a boy.

The Many Colours of Anshu is inspired by Sathe’s own journey growing up as a non-binary person in Dadar, Mumbai. Published in 2022, it is part of a growing canon of LGBTQIA Indian fiction for children that pushes against a society where the accepted norm assigns the colour blue to boys and pink to girls. In the children’s universe, Harry Potter, Famous Five and Enid Blyton books still rule. The new LGBTQIA fiction has many challenges—from getting the language right to getting parents’ approval to overcoming social prudishness.

Instead of straightforward tales with a moral ending, these stories have gay couples, non-binary people, and transgender persons as their main characters. Many authors are also questioning the “elitist and Western” language of homosexuality like ‘coming out of the closet’, ‘queer’ and ‘pride’, which they argue has little resonance with a majority of Indians. And in doing so, they are gently nudging young minds while helping parents broach seemingly daunting topics.

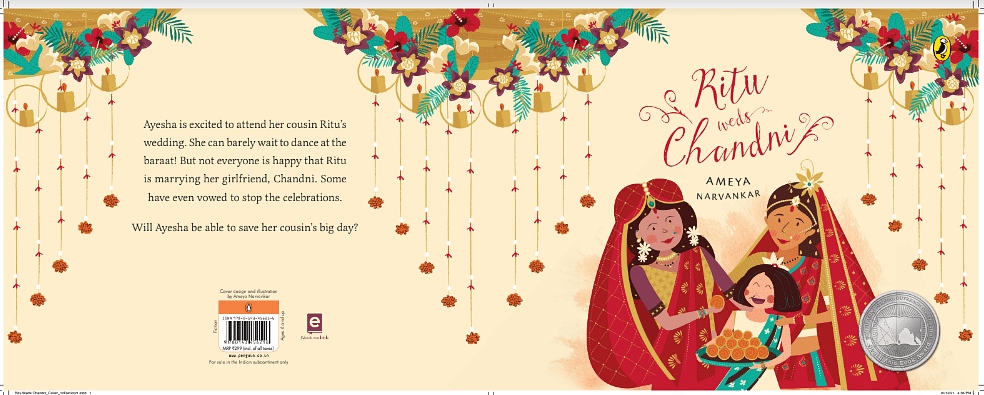

“Shielding our children from these topics is just going to hinder their development,” says Ameya Narvankar, 31, author of Ritu Weds Chandni, a picture book about two women in love who get married. “A lot of young children know what their gender or orientation is. These books are meant to reassure them and make them feel less alone.”

He wrote his 36-page book in 2015, but it was only picked up by independent publisher Yali Books in 2020.

“This is not a good book for children,” was one of the many comments Narvankar received back in 2015.

The 2018 Supreme Court judgment decriminalising homosexuality in India was a watershed moment for writers like Narvankar. Publishers started responding favourably, libraries were willing to stock their books, and people were buying them. Suddenly there was space for authors who had a different kind of story to tell.

For years, niche publishers like Gaysi Family and Duckbill Books have pioneered this genre. But mainstream houses like Penguin Random House India and Scholastic India have also opened their doors to new voices increasingly. And stores like Kitab Khana in Mumbai, Eureka Bookstore in New Delhi and Champaka Bookstore in Bengaluru are stocking them.

“We have two out of eight people walking in almost every day who specifically ask for LGBTQ-themed books,” says Venkatesh, partner of New Delhi-based Eureka Bookstore and festival director of Bookaroo Children’s Festival. Sales of books published by independent publishers are still a drop in the ocean when compared with that of mainstream ones.

In India, the marketing machine for this genre is still “covert” as Narvankar puts it.

“The marketing campaign was mostly on social media. Publishers still wanted to test the waters, which is why the sales were lower,” says Narvankar.

Also read: Family, friendship, masculinity, marriage — Delhi’s queer community tells their own story

Stories for adults and children

With Ritu Weds Chandni, Narvankar wanted to break the typical representations of homosexuality that had been popularised in Bollywood movies. A multidisciplinary designer from IIT-Bombay, Narvankar came to terms with his own sexuality during his time in Mumbai. While he was tiptoeing out of the closet, he realised that queer characters rarely showed up as main characters in books or movies.

“Queer women were hardly the centre of discussion. Which is why I chose my two characters, Ritu and Chandni. They were also inspired by some friendships I made in college, at Saathi, IIT Bombay’s LGBTQ+ resource group,” he says.

In his story, the relationship between the two women is seen through the eyes of six-year-old Ayesha, who can’t wait to attend her cousin Ritu’s wedding. But in this seemingly ordinary Hindu wedding, Ritu is not marrying a man. Her partner is Chandni, a woman. Not everyone is thrilled about this union and some family members even want to stop them from getting married.

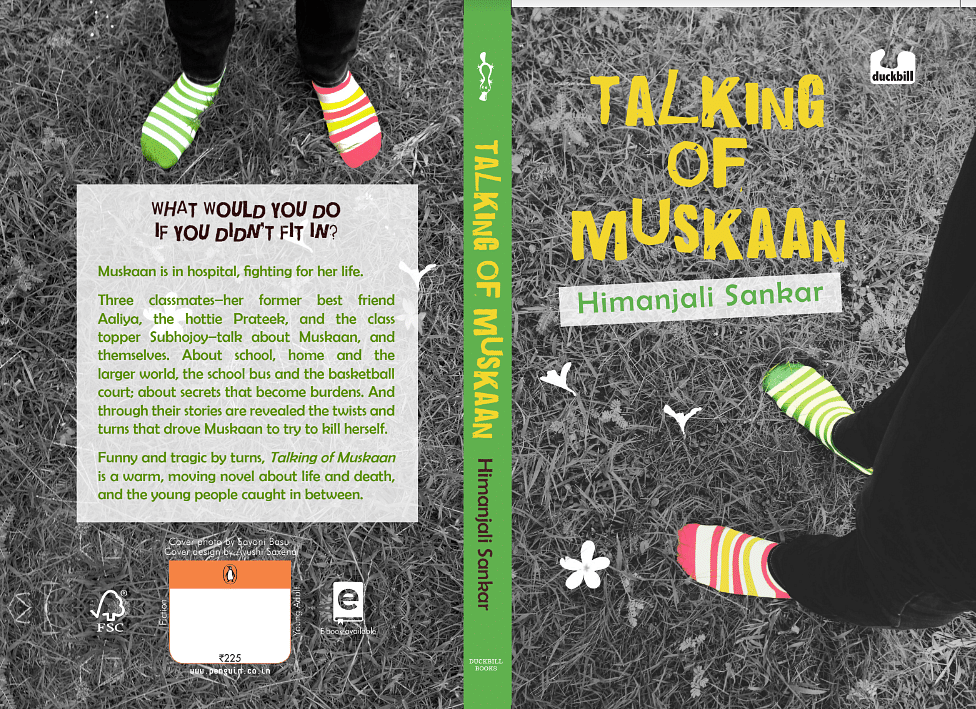

Even before Narvankar started knocking on the doors of publishers, Duckbill Books, which has been publishing inclusive books for children and young adults for little over a decade, brought out 52-year-old Himanjali Sankar’s young adult fiction, Talking of Muskaan in 2014.

While Ritu Weds Chandi has laughter splattered across the cover page with two brides in red lehengas, Sankar’s reflection deals with the difficulties faced by people who are not heterosexual. Talking of Muskaan is about life, death, and homosexuality.

Having studied in a convent school in Kolkata, Sankar drew from the experiences of her female school friends who would get bullied and discriminated against for the way they looked, their choices, and so on. At first, homosexuality was not at the centre of her original plot, with Muskaan just taking up a minor role. But after several discussions with her editors at Duckbill, Sankar decided to push the envelope by turning Muskaan from a supporting character to the protagonist.

At the time, both Sankar and her audience were navigating uncharted territory. She recalls instances of teenage students in “posh Mumbai schools” giggling and sniggering during book reading sessions. But over the years, children started stopping her at libraries and literary festivals to tell her that Talking of Muskaan makes them feel represented and understood.

“It is as much a book for adults and parents, as it is for young adults,” one reader wrote in their Amazon review of the book.

When Narvankar released his book, a few parents started reaching out to him on Instagram, telling him how they loved the story. He calls them “active and tolerant” parents, but they are still few and far between.

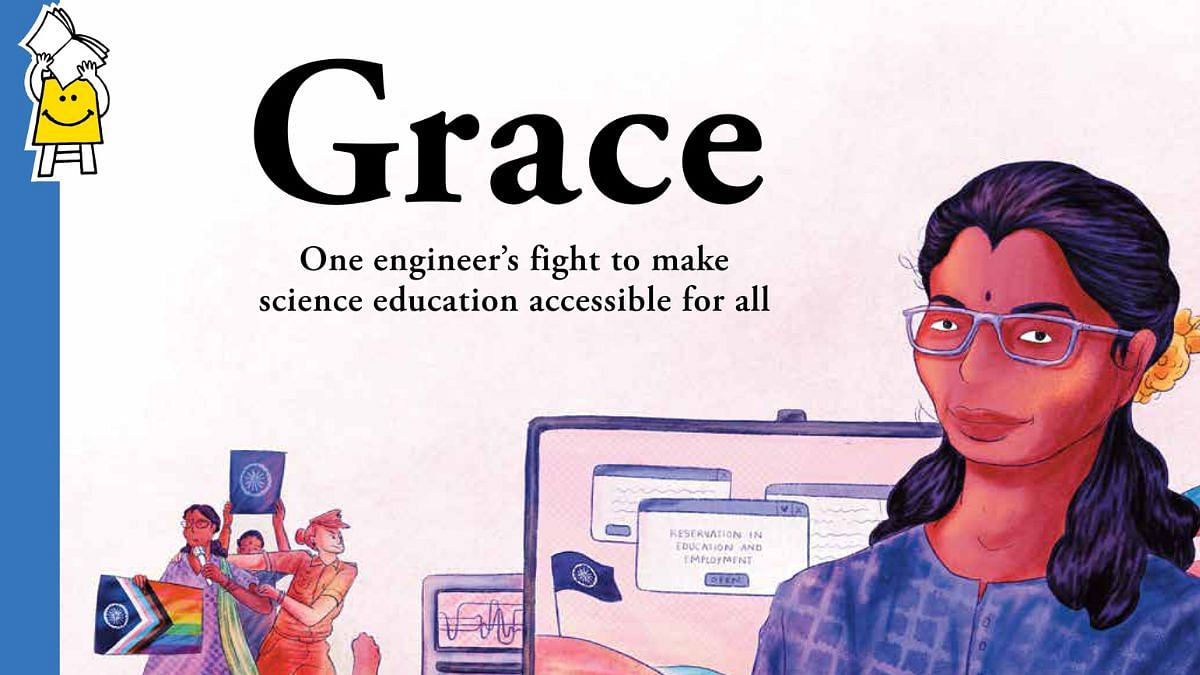

“Adults must read these books as well. We are not just raising questions for children to navigate, but we also want parents to understand what safety looks like in the home,” says Sayantan Dutta, a queer-trans science writer and author of the picture book, Grace: One Engineer’s Fight to Make Science Education Accessible for all. It is a non-fiction account of Grace Banu, a software engineer from Tamil Nadu and a Dalit transgender activist. Dutta wanted to make sure that Banu was presented as more than just a transgender activist.

“In many children’s books, women are no more than subsidiary characters or are relational like grandmothers. Very rarely do they have their own story. We wanted to, so we consciously included that she was an engineer in the title,” they add.

Also read: Queer entrepreneurs are claiming a new public place — Indian malls

Colouring outside the lines

A children’s book is more than just a story—images and illustrations play as much a role in igniting the imagination as the plot. Illustrator Priya Dali thrives on colouring out of the box for queer and non-binary children’s fiction. Her focus is more than just making the drawings aesthetically pleasing.

Dali’s characters are not just lanky stick figures. She tries to incorporate visual themes, which are all-encompassing — whether it is body shape or the clothes the characters wear.

“In picture books for children, there is a very binary representation of things. How good boys or good girls behave, or what they look like. There is an urgent need to revisit this,” says Dali, who illustrated Harshala Gupte’s, 24, The Boy in the Cupboard among a few others.

There is a local appeal to how Dali has drawn Karan, the protagonist in Gupte’s book. He has a round face and runs happily in a pink skirt. One illustration is of his mother teaching him how to drape a saree.

The Boy in the Cupboard was 13-year-old Oneeka Powale’s introduction to the transgender community—the very first time she started thinking beyond the traditional definition of gender. She received an invitation to attend a reading at The Trans Cafe in Mumbai, and enjoyed every moment of it.

“I loved the part in the story when Karan came out of his cupboard and everyone loved and supported him. He felt comfortable and cared for by his parents,” she says. “My classmates were surprised when I told them that my parents let me go to a book reading like this and that they were so open-minded because their parents might not have let them do that,” she says.

Gupte doesn’t use the word ‘closet’, which few people will identify with. Cupboard, on the other hand, is a more relatable word. The language of homosexuality and gender fluidity, which is informed by Western narratives, is something writers in India are pushing back against.

“As someone who is queer, I did not have this information or language growing up. Imagine growing up that way and then being bombarded by a flurry of such words as an adult with no context. Queerness can be a very elitist language,” says Gupte.

Dutta, too, argues that language can be exclusionary and jargon-heavy. “It can be quite anglophilic and urban.”

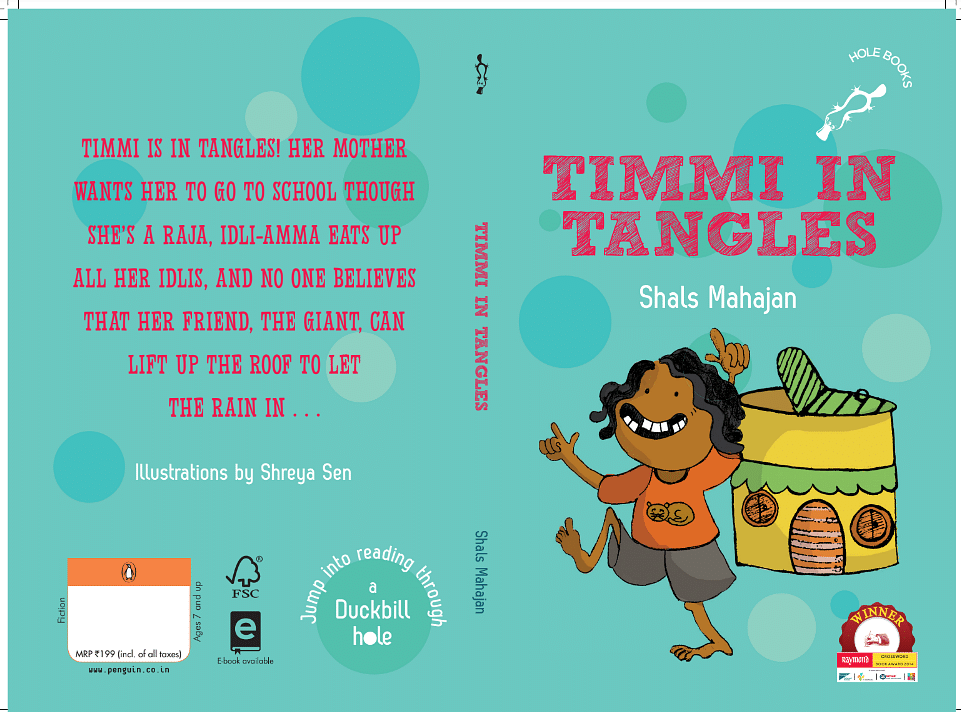

Mumbai-based author Shals Mahajan, 52,—who has written four books including No Outlaws in Gender—keeps the language simple even when untangling complicated topics. Like Sankar, they have been writing inclusive children’s books for more than a decade.

Their last book, Reva and Prisha, published by Scholastic India in 2021, is about two twins who live with their mothers, an inter-religious lesbian couple. The plot focuses on their interactions as a family. Mahajan does not feel a need to overly emphasise the lesbian identity of the mothers or attempt to be “preachy”. The process of normalisation is just a subtle underlining of their family dynamics.

“Queerness is not so evident in my books. It is simply about how the characters make sense of the world around them,” says Mahajan. They use visual tropes such as family photos or scenes of going to the beach together to normalise families where both parents are women.

A new generation of authors is not only freeing gender and sexuality from their straight-jacketed definitions, but is also interrogating gender roles at home, in public spaces and within the family hierarchy in the hope of informing their target audience—and their parents.

Also read: Delhi University is the new battleground for queer students—stigma, suppression and suicide

Rejections and pushbacks

In the push and pull of rejection and acceptance of their novels, resistance comes from parents. Even as Sankar received appreciation from teenagers, it was the adults and teachers who spoke out against her book. When Talking of Muskaan was shared with principals and teachers at Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda Arts Festival close to the release of her book, she was not allowed to address children. The festival’s organisers and school teachers were worried that their parents would object to it, she said.

Mahajan wasn’t allowed to use ‘they/them’—the pronouns they identify with—at a children’s literature festival in Bengaluru in 2018. The organisers reportedly told them it would be “confusing”.

And sometimes, criticism comes from within the family. When Gupte published The Boy in the Cupboard two years ago, her relatives accused her of writing “propaganda to make children gay.”

For the most part, this pushback is reflected in the number of books sold. Writers and publishers were not willing to discuss numbers, but many acknowledged that sales are low. Eureka Bookstore appears to be a happy exception.

“I don’t know of any book with this kind of theme, published in India that has done well commercially. These books are invariably passed over by award juries too despite their literary merits and urgent themes,” says Kanishka Gupta, a literary agent and founder of Writer’s Side, a literary agency. And like Narvankar, he argues for the need for more publicity to push these books into the mainstream.

“What is lacking is an ecosystem of influencers. I would be very happy to see celebrities, public figures, or book clubs actively promoting these kinds of books,” he adds.

Queer themes for adults

These storytellers may not be chasing cheques but they are writing for children who want to be entertained. At the same time, not all their stories are about rainbows and roses. Bullying, rejection and exclusion are some of the explored themes.

“We struggle with creating a good way to represent feelings in these books. How much of the world’s harshness of reality do we bring in? We don’t want to discourage these kids,” says Dali.

The Many Colours of Anshu is set in a more utopian world where Anshu feels safe to discuss and show their gender identity. However, in The Boy in the Cupboard, Karan is made fun of for his feelings.

“It’s not always easy to work through these scenes, and we have to very gently show the difficult side, but then eventually close the narrative in a way that the child is left feeling safe and protected,” Dali adds.

That said, a deeper maturity is seeping into LGBTQIA books for adults. Honest narratives are surfacing at full steam. Sankar, who has also been an editor at Simon & Schuster for over 15 years, has seen a dramatic shift in queer themes for older audiences.

“Themes become more acceptable over time. Later this year, we are publishing a book that deals with asexuality, something that is not commonly talked about or represented in literature,” she says.

Even the non-fiction genre is bringing out dating guides. Aniruddha Mahale, an LGBTQ activist, social media influencer and writer’s book Get Out: The Gay Man’s Guide to Coming Out and Going Out is one of them. Queer themes are showing up in various Indian language books. Ye Dil Hai Ki Chor Darwaja by Kinshuk Gupta is a Hindi book of queer short stories that was released this year, while the Kannada novel Mohanaswamy by Vasudhendra—a semi-autobiographical account of what it is like to be a gay man in India—was translated to English by Rashmi Terdal in 2016.

Among the younger audience, even though these themes may still be restricted to inclusive cafes and bookstores, conversations are slowly entering playgrounds if not classrooms.

After the reading, Powale discussed the book, not just with her mother, but with school friends as well. And soon, they were all talking about cupboards and queerness.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)