Noida: Towering over the paddy fields at Dhanauri village in Greater Noida, a pair of Sarus cranes operatically flap their large grey wings and bob their bright red heads at each other in a playful mating ritual. They pay no attention to the farmers stacking their harvest. Suddenly, a blaring horn pierces the silence. The cranes stop their dance and fly away as a truck laden with sand rumbles down the road towards the construction site of India’s largest airport at Jewar, barely 20 km from Dhanauri.

“In the next few years, all the bird calls and chirps will be replaced by vehicle horns and construction thuds if we do not protect this area,” says Surya Prakash, resident bird-watcher and a retired scientist from the Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of Life Sciences.

Time is running out. The National Green Tribunal has given the Yogi Adityanath government in Uttar Pradesh just four weeks for an update on notifying Dhanauri as a wetland. The Noida International Airport at Jewar has given environmentalists, bird-watchers, and conservationists fresh impetus, reinvigorating a decade–long fight to get the government to legally protect 112 hectares of wetlands. Earlier this month, 77-year-old birdwatcher Anand Arya approached the NGT demanding that airport construction be halted until the Uttar Pradesh government declares Dhanauri a Ramsar wetland site.

Now Yogi must balance three priorities—Jewar airport’s first flight in 2024, farmers’ compensation, and ecological concerns. All this with the NGT clock ticking.

Around 60 km from New Delhi, this patch of land filled with small lakes, marshy bogs, and paddy fields is wedged between Dhanauri, Thasrana, and Amipur Bangar villages. It’s home not just to the Sarus crane—which is Uttar Pradesh’s state bird— but to more than 23 avian species including the black-necked stork, bristled grassbird, and Egyptian vulture all of which are endangered.

Even the environment clearance given to Jewar Airport in 2020 identified Dhanauri as a wetland of conservation importance and suggested that it be notified. But any action remains trapped in bureaucratic back and forth between the state wetlands department, forest department, and the airport developer, Yamuna Expressway Industrial Development Authority (YEIDA). Resistance from villagers who own paddy fields in the wetlands and want adequate compensation has further muddied the water.

Dhanauri wetlands fulfil three of the nine criteria for a Ramsar site, though even a single criterion is enough for it to be listed as one. It supports 23 critically endangered, threatened, and vulnerable species of birds, and regularly supports 50,000 waterfowl. Most importantly, it is home to 1 per cent of the total Sarus crane population of India.

In the next few years, all the bird calls and chirps will be replaced by vehicle horns and construction thuds if we do not protect this area

– Surya Prakash, retired scientist & bird watcher

On its own, Jewar Airport does not pose a threat to Dhanauri’s vibrant ecosystem. But environmentalists and bird watchers fear that the inevitable commercialisation of the surrounding areas—hotels, shopping and residential complexes—will kill Dhanauri’s wetlands.

“When we were young we used to bird watch inside Delhi. Then the cars and trucks and buildings pushed the birds out of there and into the outskirts,” says Prakash as he walks down a dirt path between two fields.

“Now, it looks like they’re pushing the birds out of here too. How far can we follow them this time?”

Also read: India’s growing number of ‘Ramsar sites’ and why global treaty to save wetlands matters

Fight at NGT

Renown bird-watcher and environmentalist Anand Arya who took up bird watching around 40 years ago recalls the first time he ‘discovered’ Dhanauri wetlands nearly ten years ago in 2014.

“It was like walking into pure bliss. I saw over 150 Sarus cranes that day,” says Arya, who lives in Greater Noida. It was when he single-handedly began his fight to get the Uttar Pradesh government to protect it.

He immediately reached out to the Uttar Pradesh government’s environment, forest, and climate change department with a petition to declare the area as a wetland. Back then, he was worried that with no legal protection, the wetlands would be defenceless against urbanisation that was sweeping across swathes of Greater Noida. The Wetland Conservation and Management Rules allow states to identify and propose areas to be declared wetlands and be protected from encroachment, construction, and other activities that could degrade the area.

But nothing happened. And nine years later, Arya’s fears have come true. Now, he’s taken his fight to the green tribunal.

In his 3 October petition to the NGT, Arya pointed out that Dhanauri was supposed to have been notified as a wetland in 2020 when the environment clearance was given to Jewar Airport. On 16 October, the National Green Tribunal, in its response to Arya’s petition, directed the government to give an update on Dhanauri wetlands’ Ramsar listing within one month.

As the wetland is within a 25-km radius of the airport, the Wildlife Institute of India prepared a conservation plan for the flora and fauna around the area. The delineation and protection of Dhanauri is a separate clause in that conservation plan, a copy of which is with ThePrint. But the UP government and the YEIDA have failed to act on it.

During the NGT hearing, the UP Wetland Authority said the proposals for the Ramsar site and the wetland notification of Dhanauri were pending because of some missing documents. The UP Forest Department has revised the proposals and sent it back, and now they await clearance by the state Wetland Authority.

Arya is sceptical.

“There’s only one reason why it hasn’t been notified yet—bureaucratic negligence,” he says.

On the other hand, the forest department cited ownership of land as the reason for failing to notify the wetlands. Sitting in a leather chair in his office in Sector 1, Noida, Divisional Forest Officer (DFO) PK Srivastava explains that the land in Dhanauri is not entirely owned by the government. Of the 112 hectares, only 25 hectares are under the YEIDA while the rest is owned by farmers from the villages around the wetland.

“How do we notify it as a wetland when it is not even owned by us and is used to farm paddy?” he asks.

The state, however, does not need to own wetlands to be able to notify them. Rule number 7 of the Wetlands Conservation and Management Rules 2017, which outlines the procedure for notification, only says that state governments need to mention the pre-existing rights and privileges of lands that are being notified as wetlands.

To restrict the loss and degradation of wetlands, the “incorporation of linkages between humans and wetlands is necessary”, reads India’s guidelines for implementing the Wetland Conservation Rules. The guidelines allow for activities like wetland agriculture, fishing, and certain tourist activities as part of a ‘wise-use’ approach to conserving wetlands.

The Ramsar Convention too says the designation of wetlands as Ramsar sites can co-exist with their ‘wise use’. It acknowledges that human activity is an essential part of wetland ecosystems, and wetlands cannot be conserved in isolation.

The Kanjli wetland in Punjab, which was listed as a Ramsar Site in 2002, is a prime example of an area that is both publicly and privately owned. Fed by the rivulet Kali Bein, it supports both biodiversity in the marshland as well as irrigation purposes of farmers that own land in the surrounding areas. And India’s first Ramsar Site, Chilika Lake in Odisha, too, supports the livelihood of fishing communities while managing an ecosystem of migratory birds and aquatic wildlife.

Disillusionment and conspiracy theories have set in among the close-knit bird-watching community in Delhi NCR. A local bird watcher who does not want to be named is convinced that the delay in notification is because the government is hesitant to give up this land for conservation.

“This area is so close to the upcoming airport, it will see so much development in the next few years. Why would the government want a protected wetland in the middle of it?” he says.

Compensation first

Farmers in Dhanauri have heard stories of landlords in Jewar becoming crorepatis after selling their land. And they want a piece of the pie.

At the entrance of a walkway into the Dhanauri wetlands, there are two mounds of dirt with holes manually dug into them. It used to have a signpost indicating that the area is called Dhanauri wetlands, but according to resident Jawar Singh, some farmers had ripped it out.

“Nobody can come in and suddenly declare our private farmlands as public wetlands. We need compensation first,” says Singh, who lives in Thasrana village and owns around five hectares of land in the wetland area.

DFO Srivastava too sympathises with the locals. The goal of conservation, according to him, should not come at the cost of people losing their livelihoods.

“We cannot notify the wetlands without setting their rights first,” he says.

The forest department does not want to settle with farmers or offer them competitive rates. The onus should fall on the development authority, say forest officials. The department had written a letter on 15 October to YEIDA asking them to acquire the farms and pay the farmers their settlements.

Nobody can come in and suddenly declare our private farmlands as public wetlands. We need compensation first

– Jawar Singh, farmer

“YEIDA is going to be responsible for a lot of harmful developmental activities from their construction projects. I think they should be the ones to compensate the locals,” says Srivastava.

YEIDA acknowledges receiving the letter from the forest department but refuses to comment further on its plans to acquire the land.

There appears to be a stalemate—and until it is resolved, there’s a question mark over the fate of Dhanauri wetlands and the Sarus cranes who mate for life.

Also read: Wetlands are a versatile climate and biodiversity ‘hack’. But we’ve lost 80% of it

‘Wise-use’ of wetlands

For KS Gopi Sundar, who is the Co-chair of the IUCN Stork, Ibis, and Spoonbill Specialist Group, the paddy fields in the Dhanauri wetlands are a blessing.

“Sarus crane habitats are notoriously found in and near farmlands in Uttar Pradesh. Farmers and Sarus cranes have an ancient coexistence, which they both benefit from,” says Sundar.

Sarus cranes cannot swim—they prefer shallow wetlands interspersed with fields. The cranes in UP also alert farmers when nilgai enter their fields, allowing them to shoo the antelope away.

“Contrary to what people think, farmlands are not harmful but beneficial to Sarus cranes’ survival,” says Sundar. If the fields were to disappear from the wetlands, so would the cranes, he adds. “The only major threat to them is the loss of their habitat due to concretisation,” he continues.

It is exactly against this threat that bird watchers like Arya are fighting to protect Indian wetlands.

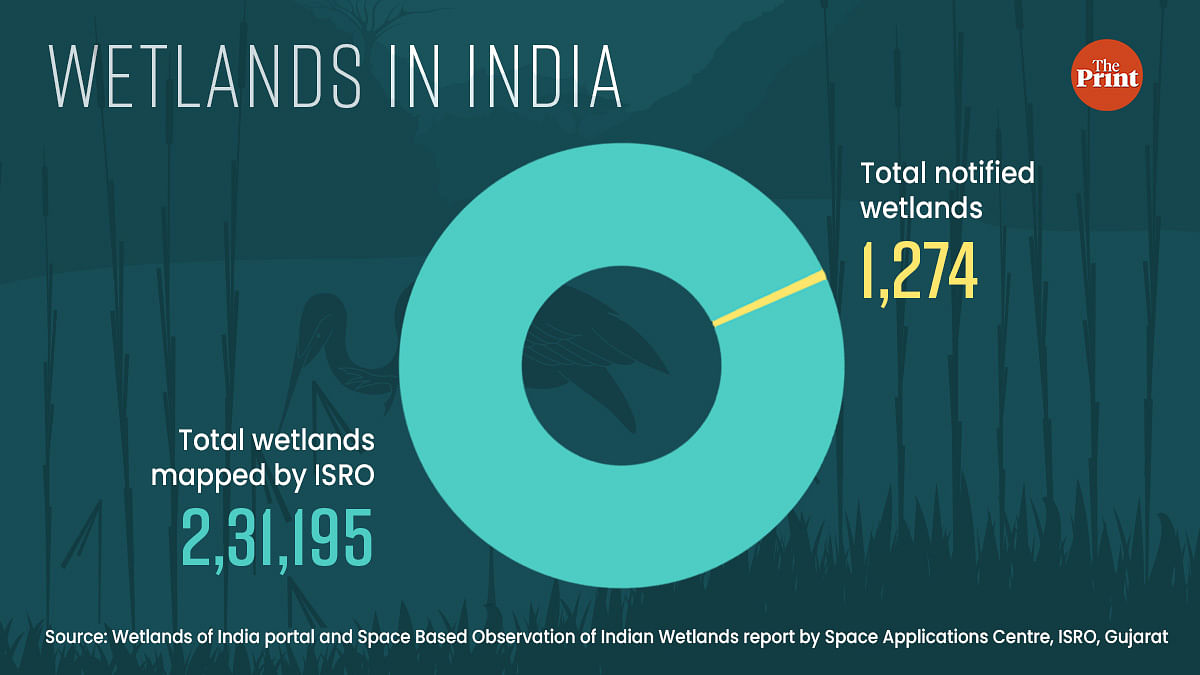

Despite a broad framework of management, India has had a poor track record in conserving its wetlands. In a satellite survey conducted by ISRO and published in 2021, 15.98 million hectares of wetlands were identified in the country— 2,31,195 wetlands that are over 2.25 hectares in size.

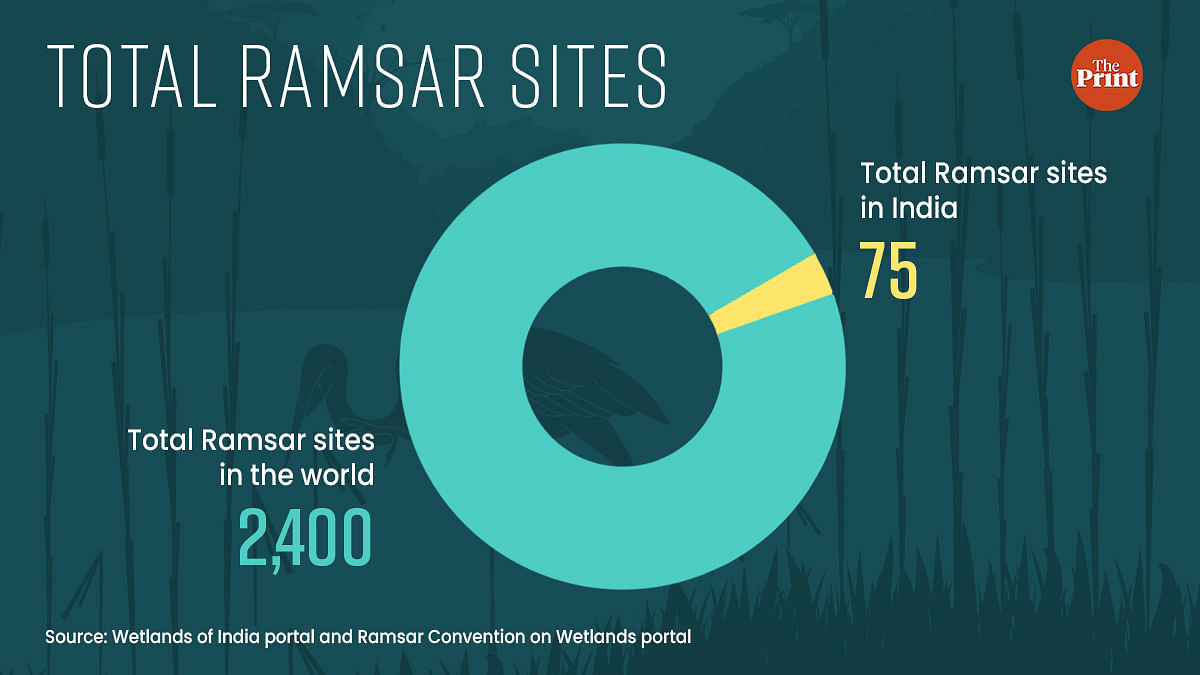

The Wetlands of India portal identifies only 1,274 wetlands, of which there are 75 Ramsar sites. The total Ramsar sites in India account for about 1 million hectares of wetlands.

Legal history is also a testament to the struggle to get the Indian state governments to recognise and notify wetlands. After the Wetland Conservation and Management Rules were notified in 2017, all states were granted one year to notify wetlands in their states and prepare ‘brief documents’ enlisting their characteristics. Despite that, Dhanauri wetlands did not feature in the UP government’s list.

Even as late as 2021, the Chief Secretary of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change wrote to all states asking them to expedite the process of notification. By 2021, only Ramgarh Taal Lake in UP and Sukhna Lake in Chandigarh had been notified as wetlands in the national portal.

Also read: Wetlands can help reach sustainable goals but not all of them are blue carbon ecosystems

The bird watchers

SP Chaudhary, a birdwatcher and a resident of Greater Noida, has seen the wetlands change in the five years since he started frequenting it. Without proper maintenance, the lakes have been taken over by water hyacinths and other invasive species. They clog the water body and do not allow high-flying birds to see there’s a wetland below.

“A few years ago, you’d find birds as far as the eye could see. It was a magnificent sight. Now, we can see their numbers dwindling,” says Chaudhary.

In his application, Arya urged the Tribunal to take cognisance of the threats faced by birds in the unprotected Dhanauri wetlands. Sarus cranes, who build their nests on the ground in paddy fields, are especially vulnerable to feral dogs that attack their chicks. Arya also mentions that there have been instances of poaching in the area.

While walking past a clump of trees towards the far end of the wetland, Surya Prakash suddenly stops and stares in wonder. Three little woven nests hang from a tree. High-pitched cheeps and squeaks emanate from within the nests.

“These are baya weavers! We would see so many of these in Delhi’s trees until a few years ago,” he says, excitedly.

Two inquisitive chicks pop their heads momentarily out of the nest, while a few other birds fly around it.

“There’s new life taking place right in front of our eyes,” he says with a smile. “It is on us to protect it.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)