Rohtak: When 35-year-old N left home after a fight with her husband and reached Kurukshetra station in Haryana, two men offered to help. They said they’d take her somewhere safe. Instead, they led her into an empty coach and sexually assaulted her. Two days later, she was found near the tracks in Sonepat, bleeding, her leg severed by a train.

Still dazed and recovering at the government hospital in Rohtak, N says the men told her they had been sent by her husband. She realised something was wrong when they put their hands on her. At least two other men allegedly joined them. They took turns raping her and guarding the door. She says she had been drugged and could barely move.

“I screamed and pleaded with them to stop touching me,” whispered N, left weak and emaciated after the ordeal. “I told them I lost my son a few months ago, they did not listen.”

After the 24 June gang-rape incident became public, there was widespread outrage online. Women spoke up about feeling unsafe at stations after dark. Poor CCTV coverage, porous entry points, and unguarded gates have turned railway stations into easy hunting grounds. These are transient spaces, often chaotic, where women travel alone, wait overnight, or fall asleep mid-journey. Among them are vulnerable groups like runaway teenagers and women escaping poverty in villages.

“When even the train is no longer safe… then where should girls go?” asked an X user. Another called it “heart-wrenching” that a woman who “thought railway travel was safe and trustworthy” could be attacked by “monsters” without anyone noticing.

I ran away from my house after an argument with my husband over physical relations, I don’t remember how I reached Kurukshetra railway station, but one of the accused, on pretext of taking me to a safe spot, where he said his wife was present, took me to a stationary coach…

-N, survivor of Kurukshetra train gang-rape

On 17 July, the National Human Rights Commission took cognisance of the matter and issued notices to the Railway Board chairman, Ministry of Railways, and the Haryana Director General of Police. It demanded a detailed report within two weeks, including whether the authorities had provided compensation to the victim.

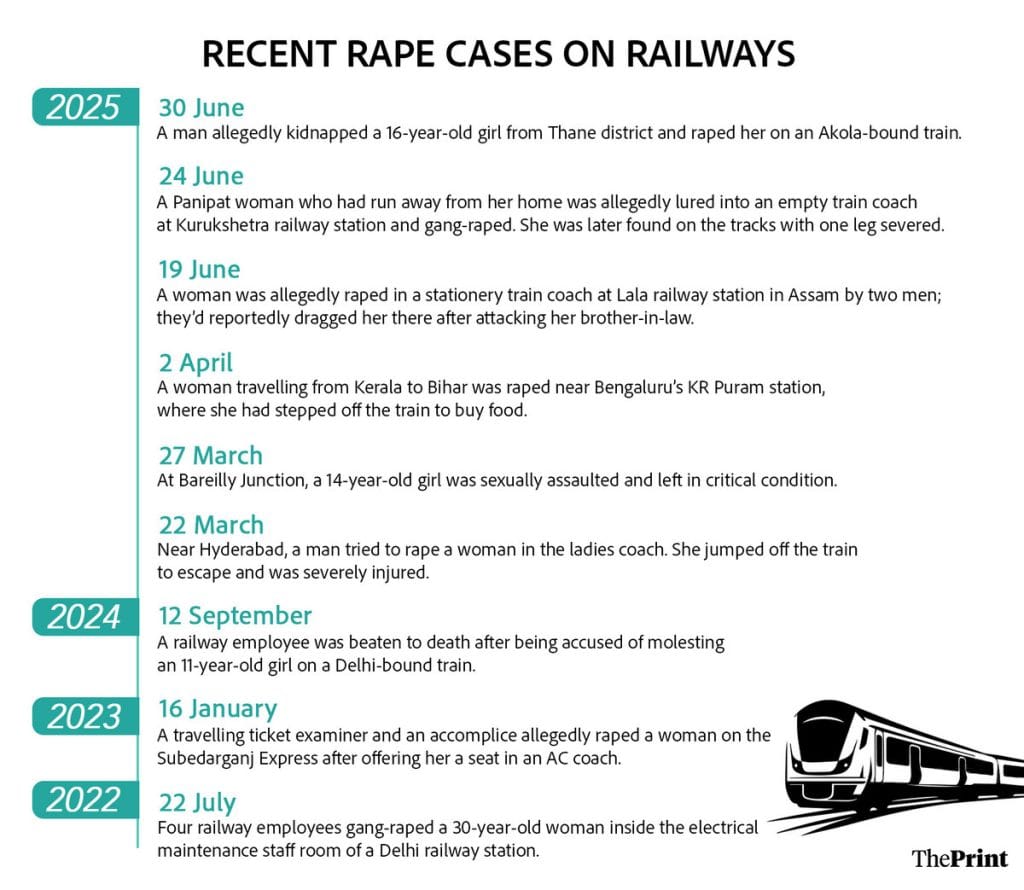

The Kurukshetra case reinforces that trains and stations have proved as dangerous as any dark alley for many women. On 30 June, a man kidnapped a 16-year-old girl from Thane district and raped her on an Akola-bound train. In April, a woman travelling from Kerala to Bihar was raped near a poorly lit stretch close to Bengaluru’s KR Puram station, where she had stepped out to buy food. A similar incident took place at Bareilly Junction in March, when a 14-year-old girl was sexually assaulted and left in critical condition after she got down from a moving train to look for her father.

Law and order at railway stations is split between the Government Railway Police (GRP) and the Railway Protection Force (RPF). The GRP, under state governments, handles criminal cases and can file FIRs. The RPF, under the Ministry of Railways, is tasked with safeguarding railway property and ensuring passenger safety, but cannot register criminal complaints.

The GRP reported 331 cases of assault against women with intent to outrage the modesty and 24 rape and attempted rape cases in 2022, according to the latest National Crime Records Bureau report. In 2019, before train travel was disrupted by Covid-19 restrictions, it recorded 224 cases of assault on women and 28 cases of rape and attempted rape. But these statistics don’t account for unreported cases, ranging from harassment and molestation to men entering women-only coaches.

“Women have raised alarms over safety issues, and a lot of measures have been introduced by both police and Railways. But unlike airports, stations aren’t sealed properties, and they’re much cheaper than buses, hence crowd management is a big issue” said Lalit Chandra Trivedi, former general manager of East Central Railway, who has worked across railway zones for 38 years. “Leveraging technology and ensuring stations remain non-porous can make them safer.”

Also Read: ‘No one can touch me’—Harassment charge against Krishna Kalpit shakes Hindi literary world

Blind spots

At midnight, Kurukshetra railway station is almost empty, save for a few men and two women. The air is sour with the smell of sweat. Some men had just been removed for loitering without tickets, a local GRP constable said.

Security has since been ramped up across railway stations in Haryana, with police now conducting routine checks to remove unnecessary crowds.

A food vendor at Kurukshetra station said most people only heard about the gang-rape after it was reported in Hindi newspapers. The platform where it happened, he added, has always been relatively deserted.

“Nobody sells their food items on the platform from where the woman had boarded the train since it remains dark and nobody goes there,” he said. “Most of the vendors shut their shop post 10-10.30 pm, as it gets dark and there aren’t that many passengers.”

Victim N, who police say was mentally disturbed, left her home in Panipat on 23 June. The irony was that by the time the assault took place, her husband had already lodged a missing complaint and police were on the lookout for her.

The details of the sexual assault are still being pieced together. Officers say N doesn’t remember how she got to Kurukshetra, about 70 km from home, so investigators are using surveillance footage to reconstruct events. A senior police officer said the assault took place on the intervening night of 24 and 25 June.

[Train] delays can be annoying, but for women, it’s risky. We avoid bathrooms, dark corners, and stay closer to cops or ticket counters, even when people are around. It’s scary

-Shalini Nagar, passenger at Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station

On the morning of 26 June, local residents found her lying near the railway tracks in Sonepat, bleeding heavily. The NHRC release says she was “thrown on the rail tracks” but police are still trying to ascertain how she got there. She was taken to a hospital there and then to PGIMS Rohtak. Her husband was informed she was there only on 29 June, he said.

A zero FIR was first registered at Quila police station in Panipat, after which the case was transferred to the Panipat GRP. It’s now probing the matter along with an SIT of the Haryana Police.

So far, three people have been arrested—Bhajan Lal, a railway technician at the Kurukshetra station, and labourers Shivam and Gulab Singh. All three have been booked under section 70(1) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita for gang rape.

The three accused have confessed to the crime, according to the Principal DG,PIB, who added, “There are five more accused, who are yet to be identified”.

With N unable to recall the route or the assailants, police used CCTV footage from roads and railway premises to identify the suspects. Investigators described the case as “blind”.

At PGI Rohtak, N sits pale and exhausted in the ward. She’s wearing a faded green kurta, with the fabric of her salwar hanging loose where her leg was amputated. Her two children, aged eight and ten, cling to their father at the bedside, watching him scroll through his phone. Under trauma, she struggles to speak.

“I ran away from my house after an argument with my husband over physical relations, I don’t remember how I reached Kurukshetra railway station, but one of the accused, on pretext of taking me to a safe spot, where he said his wife was present, took me to a stationary coach,” she said in a shaky voice. “I was then drugged and I could barely remember anything, I started to feel unconscious, but I remember pleading for help.”

“Police bring suspects to the hospital for her to identify as her memory is not clear,” said her husband, who works as a labourer.

N remains largely still. Sometimes she glances out the window, sometimes at her amputated leg. Mostly, she’s silent.

What night means for women

At Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station in Delhi, the lights are bright, but Shalini Nagar, a 33-year-old private company employee, looks uneasy. It’s 1 am and her train to Mumbai is delayed. She steps away from the bustle and finds a spot to smoke, clutching her phone tightly and scanning her surroundings.

“Delays can be annoying, but for women, it’s risky,” Nagar said. “We avoid bathrooms, dark corners, and stay closer to cops or ticket counters, even when people are around. It’s scary.”

Fear of being followed, groped, watched, or threatened has long been a reality for most women at railway stations—big, intermediate, or small. Whether there’s a crush of people or empty platforms, safety is always uncertain, particularly after dark.

While we have CCTV access at all stations, it’s difficult to maintain. Usually, there are more non-functional CCTV cameras, than functional

-Deputy SP Ghaziabad (Railways) Sudesh Gupta

About 13 km away, Anand Vihar station on the Delhi-Ghaziabad line appears orderly at first glance. Cops are on guard. Halogen lights line the entrance. Tea vendors and coolies bustle about. But as the clock inches to midnight, the crowd begins to thin. Auto and cab drivers start hovering, staring, following passengers, striking up unwelcome conversations with women who try to ignore them or move away.

At Kurukshetra station around 10.30 pm, there’s less activity but a similar sense of discomfiture. Gurpreet Kaur, 55, clutches her backpack as she waits for a train to Pathankot. She’s visibly tired but alert, travelling with five family members because “it’s safer that way”. She sits under a rusted shed lit by a single tubelight—near people, never alone.

“It’s abandoned,” said Kaur, pointing at the empty platform. “There’s barely any CCTV or streetlights. Anybody can walk in.”

‘Slow changes’

“Women’s safety” has been a buzzword for the Railways in recent years. Seven major stations are set to get AI surveillance and facial recognition. Some zonal railways have added brighter lights in ladies’ coaches. A 24×7 distress hotline is in place. And in 2023, the Amrit Bharat Station Scheme was launched to modernise 1,275 stations and improve safety.

But the existing infrastructure is still full of gaps and fear lingers.

Gurpreet Kaur said the transformation is not fast enough.

“Earlier, there were more crowds, but now, people take cabs, or have private vehicles. Fewer people are coming to the station, and women avoid late night trains. It doesn’t feel safe,” she added, echoing the concerns of several women who spoke to ThePrint.

A senior GRP officer, who did not want to be named, said police and railway teams are planning to rework the lighting inside and outside stations, including adding streetlights so there are no dark stretches.

We’re planning to reinforce security measures against those seeking shelter at railway stations. To remove unwanted crowds, we’ve asked our officers to identify people who are often loitering around. Along with the RPF and CPF, we’re working on more security drives

-Rajesh Kumar, GRP DSP(Faridabad)

In a written response in the Rajya Sabha in March this year, Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw listed several measures meant for enhancing women’s safety, including escort teams on trains, including female RPF personnel on vulnerable routes, expanded CCTV coverage, and increased patrolling.

He noted that the ‘Meri Saheli’ initiative, introduced in 2020, now covers around 500 long-distance trains daily through 250 RPF teams, and that more than 1.1 lakh men have been penalised for entering women-only coaches.

“The deployment of security personnel in trains is decided based on the vulnerability of the concerned trains/sections, timing, location of the area, threat perception of the hinterland, analysis of past crime of data among others,” the response added.

But women like Kaur and Nagar describe a very different reality. Whether they’re in sprawling urban hubs or small towns, railway stations still often slip into shadow after it gets dark.

Also Read: Balasore student who self-immolated wanted to be a teacher. In death, she taught how to stand up

‘Stuck’

On the outskirts of Greater Noida, Dadri railway station has no cop or guard in sight at 11.20 pm on a muggy July night. Tucked far away from the city, its porous entry and exit points make it easy for men to loiter.

Among the few waiting is 19-year-old Suman Kumari, newly married and heading home to Hoshiarpur, Punjab. She lives nearby with her husband, who had dropped her off at the station. On the dimly lit platform, she looks confused, unsure where to go.

“There are no policemen, no ticket counter, and nobody to guide me. If I miss this train, how do I get back?” she said.

Only one guard is visible. Most trains pass through without stopping. The few that do are usually freight.

CCTV cameras aren’t visible at Dadri, and nor indeed at many other stations in NCR visited by ThePrint. They’re either missing from key locations like foot over bridges and dark platforms, or are not functional.

“While we have CCTV access at all stations, it’s difficult to maintain. Usually, there are more non-functional CCTV cameras, than functional,” acknowledged Deputy SP Ghaziabad (Railways) Sudesh Gupta.

He accorded much of the blame to “rats”, which he said are a common problem at all railway stations and damage CCTV wiring.

Gupta said each station is supposed to have a women’s help desk staffed by a female constable, but none were visible at any of the stations visited at night. At most stations, he added, four to eight GRP constables and one sub-inspector are deployed, depending on the need. Remote stations that see mostly freight traffic are manned by just two constables working staggered shifts.

About 120 km away, Karnal railway station looks more secure at first. It’s located between dense residential colonies, and by midnight, migrant workers begin arriving from neighbouring districts. Some are inebriated. GRP cops patrol the platforms, using wooden canes to disperse people without a valid reason to stay.

“Only four to five of us guard the station,” said one constable.

There’s no metal detector or baggage scanner visible at the gate. The CCTV cameras are scattered. The VIP lounge is locked, and the bathroom is well away from the entry gate.

No female passengers are in sight. Jyoti and her husband, who live nearby, run a small dhaba just outside. She packs up her things quickly.

“We leave before it gets too late. Lately there’s been more police presence, but it’s not enough to feel safe. When the drunken men start gathering around, we don’t engage. They can start misbehaving,” she said.

GRP DSP(Faridabad) Rajesh Kumar said Haryana has 222 railway stations, big and small, and more measures are being planned to remove loiterers.

“We’re planning to reinforce security measures against those seeking shelter at railway stations. To remove unwanted crowds, we’ve asked our officers to identify people who are often loitering around. Along with the RPF and CPF, we’re working on more security drives,” he said.

On 26 July, N finally returned home to Panipat. After nearly a month confined to a hospital bed, she is now in a wheelchair. Adjusting back to her routine has been difficult. She struggles to cook for her children, though they help carry her around as best they can.

“Whatever happened, I want to forget,” she said over the phone, her voice faint. “There’s nothing else left for me, I’m only stuck here.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)