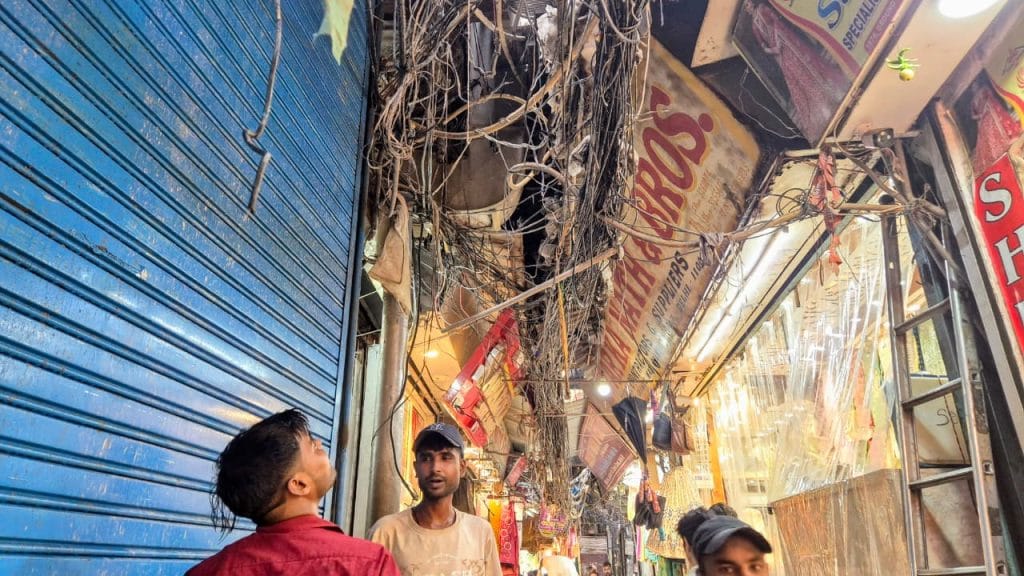

New Delhi: Every day in the morning, Bhagwan Bansal says a little prayer—let another day pass without the market burning down. Trapped in a narrow gully captured by a mangled mess of live wires, bundled up in the skyline above him, he constantly fears for his safety.

“We are sitting on a live inferno, which could explode any day,” Bansal, General Secretary of Delhi Hindustani Mercantile Association, said from his shop in Katta Shehenshai market in Chandni Chowk. “So many markets and shops have burnt down recently because of a short circuit here and there. Anything could happen,” he added.

From ancient markets to newly built neighbourhoods, Delhi has been choking under the grip of precarious wires, slithering like grotesque tentacles through its lanes, entering countless shops, houses. Most of them are dead, flammable wires that pose a fire risk. One unnoticed spark, and all hell could break loose.

Telephone, wifi, electricity, cable—old and new lines—snarl together into monstrous, sagging bundles. Poles and towers stoop under their weight. Seen in every Indian city, they are the starkest symbol of our unplanned urban sprawl. Dead and live wires hang side by side; redundant cables are never cleared. Monkeys and birds are electrocuted mid-leap, residents live caged in a web of fire and shock hazards. These jungles of wire are more than an eyesore; they are disasters-in-waiting, born of decades of chaotic, unregulated urban growth.

Delhi’s wire tangle is the product of incremental DIY electrification layered with deregulated telecom growth. While successive governments have announced undergrounding drives—from Dr Harsh Vardhan’s 2015 plan to CM Rekha Gupta’s 2025 pilot—implementation falters on cost, coordination and enforcement. Meanwhile, fires and electrocutions tied to short-circuits continue to rise. Fires claimed 1,303 lives in the city last year.

This is not just a Delhi problem. India records 30 deaths due to electrocution every day, the highest in the world. Three per cent of all accidental deaths in 2022, according to NCRB data, could be attributed to electrocution. In 2022, 12,971 people died due to electrocution, the last data available for such deaths. Separately, 423 people died in India by ‘touching electric wires’. And in the same year, 1,567 fires caused by electrical short circuits claimed 1,486 lives.

“Huge neighbourhoods of Delhi could turn to ash at any moment. The city stands on pure luck,” an official from Delhi Fire Services said on condition of anonymity.

Now, Chief Minister Rekha Gupta has made a bold new promise to the city’s constituents: “ A time will come that not a single wire will be visible overhead,” she said in July, while inaugurating pilot projects to underground wires.

Delhi government budget 2025-26 earmarked Rs 100 crore for the undergrounding of wire cables. Speaking to ThePrint at a press meet at his office, power minister Ashish Sood said that further developments on the project are underway.

“Pilot projects are currently underway. But we’ll need to liquidate assets to the tune of Rs 27,000 crore,” Sood told ThePrint. “We don’t like seeing all these wires degrade Delhi’s pride. It is our dream that the capital becomes wire-free,” he said.

Also read: Indian cities are turning to IITs, tech startups, drone data to solve urban flooding

Constant fear

From a jugmug (lit up) shop in Bhagirath Palace filled with lamps, fairy lights, and overhead night lights, Ramesh Kumar’s shop has been reduced to a bunch of cardboard boxes on the road, where he sells table fans and heaters.

Behind him is a blue tin shed where his shop once stood. It was engulfed in flames in 2022 when a short circuit caused a fast-moving fire. It burnt down more than 100 shops in the area, causing damage running into hundreds of crores.

“I didn’t get a single rupee in compensation. Nobody came to ask me how I am managing,” Kumar said, breaking into tears.

Three years after losing his shop, Kumar is not the only one selling his goods from platforms made of cardboard. The market’s wire problem has still seen no reform.

Bhagirath Palace is an electrical fittings market. Even in the morning, it is lit up by neon lights, and lamps. The skyline is dominated by thick electric wires criss-crossing each other. Smaller wires are clumsily woven into the larger web. Some narrow streets are even devoid of sunlight because of dense wires.

“The electricity wires are not the main culprit behind the fires spreading. A majority of them have been insulated. Telephone wires, internet cables have bunched up on the electric poles, and fire spreads rapidly because of these wires. You can see the absolutely ugly wires everywhere in this market; they should be removed,” Ajay Sharma, president of Bhagirath Palace electric shopkeepers association, said.

In June 2024, more than 100 shops were gutted in a fire caused by a short circuit in Marwari Katra. In July 2025, a fire broke out in Delhi’s Sadar market, affecting 10 shops. The shopkeepers blamed it on old wiring,

“The majority of fires are caused due to short circuits. An extra overload of metres and multiple injections of switchboards are causing fires. Markets and houses are growing vertically if not horizontally. Inside people’s houses, the wiring is decent, but outside it is haphazard. It is not possible for transformers to take so much load,” an official from Delhi Fire Services said.

The official added that the neighbourhoods and markets lack ventilation, and it is difficult for fire engines to get in to provide immediate relief.

NCRB data shows Delhi recorded 29 cases of electrical short circuit fires in 2022, which claimed 48 lives.

Near these neighbourhoods and markets, electric meters sit crammed together, thick bundles of cables bursting out of every box. Shopkeepers say small fires are a daily occurrence. The walls above the meters are blackened with soot. Most blazes start when these overloaded wires overheat, their insulation melting and igniting whatever is nearby.

According to data collected by the Delhi Fire Services, more than 31,000 fire incidents were reported in the city in 2023-24. They claimed 1,303 lives and injured 3,232 people.

“I sit here all day in my shop, thinking how I would escape a fire if it were to break out. This is a flammable textile market. These lanes are 4ft, 6ft, and a maximum of 8ft wide. There’s no way for a smooth exit in the event of a fire,” Bansal said.

The risks posed by entangled wires have been flagged by different authorities repeatedly. Even in 1995, the Delhi Disaster Authority had estimated that 70 per cent of fire incidents were reported because of short circuits. It had recommended a major investment to mitigate this fire risk.

“Short-circuiting is often a result of illegal connections and low-quality wiring. Therefore, even if a single major cause is taken care of, it would not only lead to saving innumerable lives and properties but also cut down on expenditure incurred on fire mitigation,” the DDA said 30 years ago.

Yet nothing has changed.

Also read: New Gurugram to have New York-style Central Park, Disneyland. First fix roads, drains

Timeline of an empty promise

An entire lane of BH Block in Delhi’s Shalimar Garden has been dug up. And people are rejoicing.

A team from BSES is working on a “war scale”—they’re aiming to remove five kilometres of overhead wires in a span of three months.

“There used to be so many fights in the neighbourhood because of the wires; one allegation or the other would be levelled for intruding on someone’s property. I am extremely happy that they’re going to go,” Inder Singh, a resident of the area, said.

This is Chief Minister Rekha Gupta’s constituency, and a pilot project to see if Delhi’s dream to rid itself of overhead wires can be realised or not.

Just five kilometres of overhead wires are costing the state government Rs 8 crore to get rid of. That is 8 per cent of the city’s budget to tackle overhead wiring. It shows how expensive the task in front of the government is.

These wires will be laid underground in a 10-kilometre low-voltage network and 1.2 kilometres of high voltage. The government is also installing 23 new blue-coloured feeder pillar boxes to replace electric poles.

“The execution of the scheme will ensure 24×7 power supply, even in bad weather,” a statement by the government read.

The project has been expanded to include Janakpuri’s C4E Block, where two kilometres of high-tension wires are being laid underground. The project is set to expand to the Safdarjung Development Area and Malviya Nagar.

Small sections of Delhi have been freed from the pest-like wires earlier, too. During the G20 clean-up, the municipal corporation moved swiftly to deal with the overhead wire mess and gave a ‘facelift’ to the main roads in Mehrauli and Daryaganj.

Back in 2007, BSES had submitted a proposal to the power ministry, with a detailed project report to lay underground wires at a cost of Rs 280 crore.

In 2009, then Chief Minister Sheila Dixit had asked the centre for funds to remove overhead wires. The government then was intent on using Delhi Metro’s technology of micro-tunnelling and trenching to lay underground wires. The project, only for old Delhi, was estimated to cost Rs 1,000 crore.

In 2011, the Shahjahanabad Redevelopment Corporation was allocated Rs 25 crore to provide ‘ducts’ to improve city aesthetics. “Shahjahanabad Redevelopment Corporation will provide ducts along all major roads in the Walled city area so that cables of electricity, telephones, etc. may be channelised through these ducts only and the historic walled city appear neater and more aesthetic,” reads the budget speech from that year.

In 2023, then Delhi cabinet minister Atishi Marlena had said that the municipal corporation and the power department were drafting a policy to control the fire menace.

But from 2011 to now, Delhi’s budget has not allocated money toward the handling of overhead cables. The jungle in the sky has only grown exponentially throughout the years, as more and more houses demanded internet, electricity and telephone connections.

ThePrint tried to reach power secretary Shurbir Singh via email, phone calls and WhatsApp messages to enquire about policy reforms. The article will be updated with his response.

Bureaucratic hurdles

Delhi’s youngest corporator, Rafiah Mahir, had to arrange three lorries to carry wires out of a market lane. The market association had pooled their resources together to get rid of bunches of overhead wires. The 24-year-old young corporator couldn’t do anything but offer external support.

“It is not in my hands to remove these wire cables, but I offer support to neighbourhoods and markets that want to get rid of them,” Mahir told ThePrint at her office in Churian Wala Lane in Chawri Bazaar.

Electric poles heaving under the weight of wires dot this neighbourhood. In some streets, the wires hang so low that even rickshaws get entangled in them.

“Along with Arif Mohd Iqbal, the MLA of the area, we’re trying to cut dangling wires in the neighbourhood along short stretches at first. The biggest issue we face is identifying the authority which is responsible for removing these wires. The roads are under the jurisdiction of MCD, while the electric poles are under BSES,” Mahir told ThePrint. She also added that the wires have absolutely no resale value in the market; they only end up in landfills.

“We don’t have any proper way of disposing of these wires. It is difficult to identify stakeholders. We’re trying removal in patches. We have underground wires from Ajmeri Gate to Hauz Qazi Chowk,” she added.

Tempers run high among the residents in these narrow lanes. They are frustrated by the lack of initiative from successive governments. It’s a reality that they’ve reluctantly accepted.

“I have been sitting here (in this shop) for over 40 years now. This wire problem will never be solved,” Irshad Ahmed, a resident in Chawri Bazaar, said. “Every other day, wires dangle right on the streets. The government is waiting for a big disaster to happen. They’ll try to solve this issue only when that happens,” he said.

The live wires can also lead to a disruption in the power supply. “These wire poles sometimes get stuck in trees and disrupt the power supply. We had written a letter to our MLA last year to solve the wire mess, but nothing happened,” Sharaf Sabri, President of Jangpura RWA, said.

A BSES official, on the condition of anonymity, said a majority of electric cables in the walled city have also been insulated, but the discom cannot be responsible for dead wires hanging on transformers.

“Internet companies are supposed to pay BSES rent to use the electric poles, but anyone and everyone illegally puts their wires on the poles. What are we supposed to do? Only targeted government intervention, like Rekha ji has brought forth now, can solve the issue,” he said.

These labyrinths of wires, thick enough to block sunlight, also cause mental stress to residents, especially during monsoon. “We don’t know if the next step we take in the rainy season could be our last,” a resident said, emerging out of his shanty, where wires were dangling below his head.

“We complain about these wires so many times, but nobody listens to us. Even monkeys have died on these electric poles,” Sangeeta, a resident of Churian Wala Lane, said.

Mukherjee Nagar’s residents are still coming to terms with the electrocution of a UPSC aspirant in the monsoon last year. The wire mess remains as is.

Pushpendra, who has been in Mukherjee Nagar for 30 years, said the entire student community lives in fear.

“Nobody has time to think of fire hazards; students have to think of their studies like robots. They think of exams, they don’t have time to think of dying,” he said.

Also read: Faridabad farmhouses vs Aravallis isn’t over. It’s a war that has just begun

A colonial mess

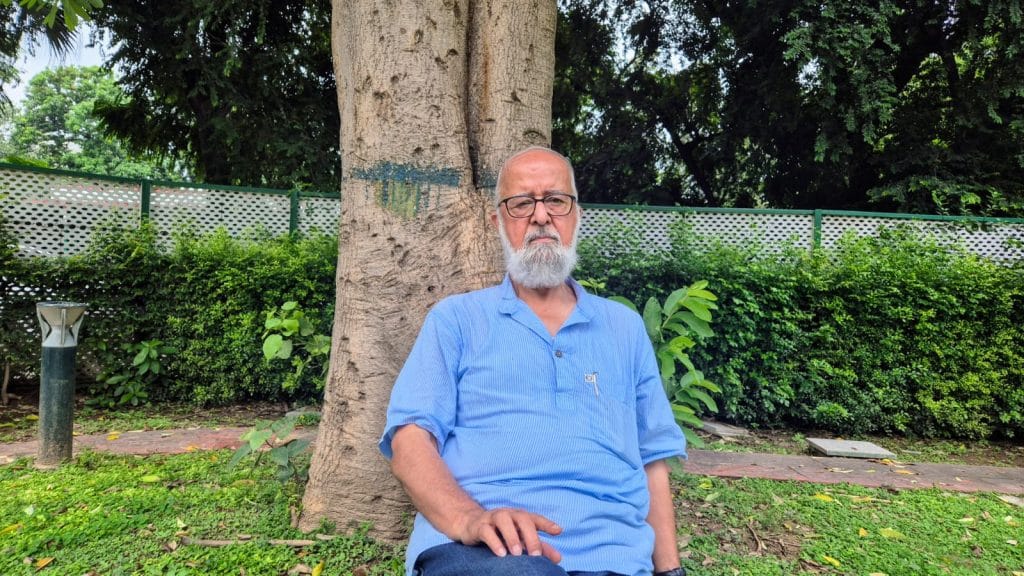

At the break of the 20th century, in 1903, historian Sohail Hashmi said, Delhi was preparing to welcome King Edward VII to the Red Fort. As part of those preparations, Shahjahanabad got the first taste of electricity. Two huge generators were placed in the town hall in Chandni Chowk.

“Agents of the power corporation went door to door spreading the gospel of this magic they had brought to Delhi’s doorstep: light at night. Whoever wanted a connection, an electric pole was fixed in front of their house, and a wire was allotted to them. Gradually, this mesh of wires spread around the city, and by the time India got Independence, wires had already taken over Shahjahanabad,” Hashmi said.

The network of electric poles would go on to entertain new connections for more technology as it was developed. From telephone connections in the houses to wifi cables, all wires took the support of these electric poles, making a matrix of their own, growing on Delhi like abominable pests.

Even today, 80 per cent of the overhead wires in Delhi are dead wires.

Hashmi added that in post-Independence Delhi, when the population swelled to 14 lakhs and refugee colonies came up haphazardly, the old Delhi wire mess was duplicated in these areas.

“As more and more people came into the city, the government was focused on giving basic electricity, telephone supplies to Delhi’s new citizenry; nobody had time to think about the entanglement of wires,” he said.

Hashmi called the wires a colonial curse. He argued that while Europeans had started undergrounding wires fairly early, the same focus was not reserved for the colonies, where overhead wiring was chosen. He cited Singapore as a good example of undergrounding of wires.

Nithya Ramesh, director of planning and design at Jana Urban Space Foundation, argued that overhead wiring is not the main villain, and undergrounding is not the only answer. Undergrounding is time-consuming and expensive, citing examples of international cities, she argued India needs mandatory standards for overhead and underground electrical cabling tied to street design covering safety, design, aesthetics and functionality.

“A lot of cities, both in the global north and in the east, still have overhead cables. Only a few cities in Australia, like Melbourne and Sydney, enable underground cabling. Tokyo also does only overhead cabling. The only difference is that there are very stringent safety standards and design manuals, even for overhead cabling, so it doesn’t cause any loss to life,” Ramesh said.

In India, wire laying guidelines for electrical wiring installations are governed by various standards, including Indian Electricity Rules, Indian Standards (IS codes), and specific technical specifications provided by bodies such as the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). These guidelines cover aspects like cable types, laying methods (underground, ducts, trays), protection, testing, and commissioning.

Overhead wires should have a minimum breaking weight of 350 kg. Low-voltage lines cannot have a height less than 5.08 metres (low voltage). Indian rules also state that every telecommunication line on a high voltage line will be treated like a high voltage line.

“Where a telecommunication line is erected on supports carrying a high or extra-high voltage power line, arrangement shall be made to safeguard any person using the telephone against injury resulting from contact, leakage or induction between such power and telecommunication lines,” the rules read.

Sri Lanka’s electricity rules of 2009 were updated in 2016. It states that overhead wires with telecommunication lines should be “made dead” or covered in insulation. Electrification rules state that overhead wires should not be less than 5.5 metres in height and should be insulated or surrounded by insulation. The rules also direct “relevant persons” not to use any overhead lines which are not compliant with the country’s grid code. It also asked the licensee and distribution agencies to mitigate risks. Risk mitigation is embedded clearly in their rules.

“Relevant persons shall take reasonable steps to ensure that the public are made aware of the dangers which may arise from activities carried out in proximity to overhead lines and to indicate the means by which those dangers may be avoided,” the rules read.

In the crowded Old Delhi underground, cables might not even find a space.

“Water lines, sewer lines, high tension lines are all running underground; there’s no space to dig up or place wires,” Mahir said.

But cities across South Asia are getting rid of the overhead mess. China’s Exim Bank funded projects in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, for underground cables. Colombo in Sri Lanka has carried out projects to underground more than 200 kilometres of cables, in the largest project of this kind ever undertaken in the country. Tokyo also tried to swiftly get rid of overhead cables before the Olympics. It had launched the ‘zero pole goal’, but it was projected to cost the city 6.8 billion dollars.

This is why Ramesh said that undergrounding all at once is not a practical goal.

“It is completely unfair of us to expect cities in India to go underground all at once; we need to plan it in phases,” she added.

As Delhi strives to achieve its dream of being free of overhead wires, residents wait for the day projects move past the constituencies of the Chief Minister and the Power Minister.

“I have been working here for two months, day and night, to ensure these wires go underground,” a worker at Shalimar Bagh said. “The conditions in my neighbourhood in Vasant Vihar are much worse. I wish to see the day I work on underground cables at my home, too.”

This article is part of Urban Pressure, a series on how bad planning is choking Indian cities.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

I guess socialism stopped the govt of 1947 from going underground.

I thought Lord Kejriwal had cleaned this mess as the CM of Delhi. I thought he had roamed the streets with a pair of pliers in his hands and had cut those wires.