New Delhi: For many decades, the world of Hindi literature continued on cruise mode, with masters such as Premchand, Nirmal Verma, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Yash Pal, and Agyeya ruling the university classrooms and bookshelves. And then everything changed with economic reforms and Mandal politics. A new surge of writers, especially from Dalit and tribal backgrounds, emerged with their own rendition of lived experiences that dared to upset the Savarna-Left consensus in Hindi literature.

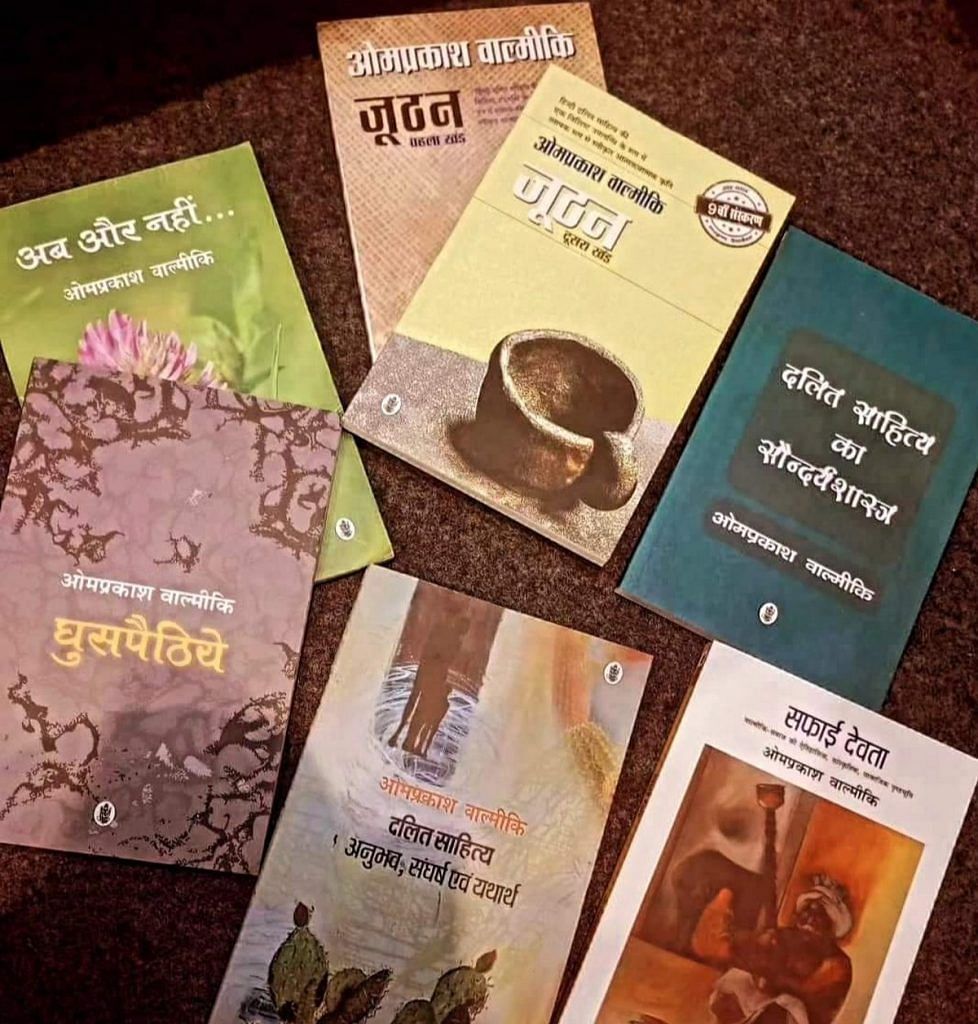

Like Kanshiram’s famous gesture of flipping his pen to signal revolution, Hindi literary writing was upended in the mid-1990s. The seminal autobiography Joothan: An Untouchable’s Life by Omprakash Valmiki shook the literary world in 1997 and became a before-and-after moment in Hindi literature. Since then, Joothan has become the top reference point in Dalit literature and a prominent part of new Hindi-lit classrooms in colleges.

Valmiki’s recounting of a childhood incident—waiting with his mother and sister outside an upper-caste household with a tokri (basket) for leftovers from a wedding feast but receiving only humiliation—exposed the raw realities of Dalit life.

“Durga appeared in my mother’s eyes that day,” Valmiki wrote in the book. “After that, mother never went to their door and collecting joothan also stopped with that incident.”

Such incidents were common in the rural Hindi heartland but rarely made it to literature—and when they did, it was through the prism of pity, not anger.

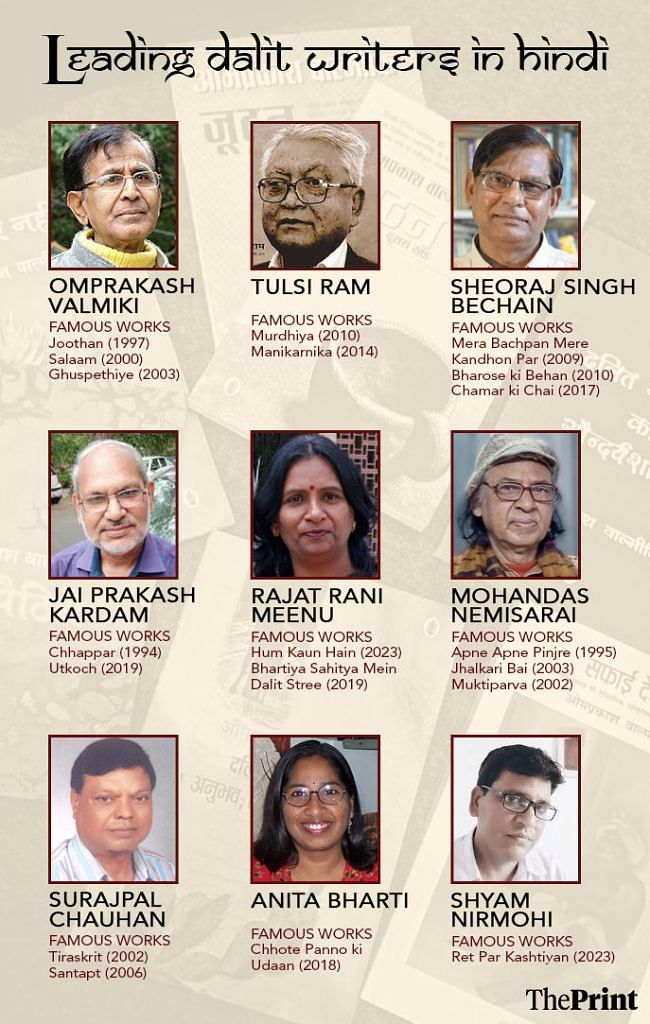

“The traditional literature lacked diversity. The lives of Dalits, tribals, and women were largely left out, but started surfacing after 2000. It can be called a journey from empathy to self-representation, which brought a vibrancy to Hindi literature,” said Sheoraj Singh Bechain, a Dalit professor, writer, and former head of the Hindi department at Delhi University (DU).

But two decades on, with new dominant politics and a changing India, Hindi literature is at a crossroads. Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi (DBA) writers like Omprakash Valmiki disrupted the old order, but they still hold only a small space among modern literary classics.

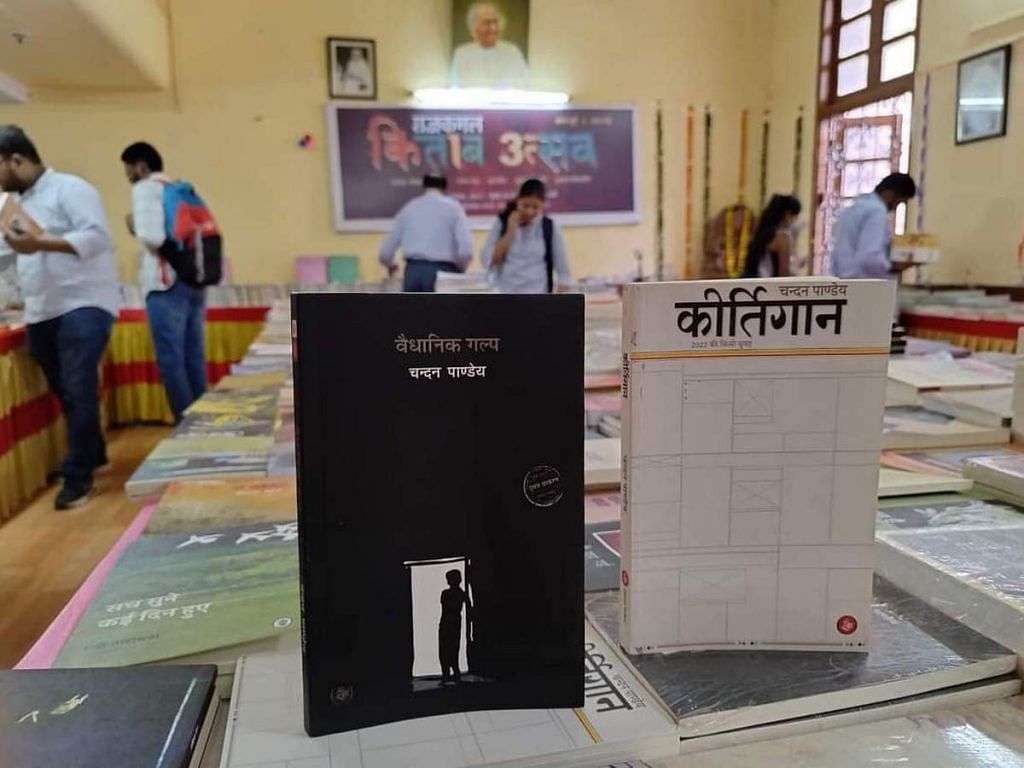

While a new crop of ‘serious’ authors, including Savarnas, are tackling hot-button themes—like Chandan Pandey’s Kirtigaan on mob lynching, and Pravin Kumar’s Amar Desva on citizenship in the COVID-19 era—a big question hovers: Is Hindi literature evolving, or merely adapting to survive?

Premchand wrote with a big vision, but today’s literature is stuck in the moment. More is being written on current topics, but it lacks the same depth. That’s why noted writers are not emerging in Hindi

-Prabhat Ranjan, writer and professor

Fresh voices are injecting energy, but there are currently more Chetan Bhagats of new Hindi writing than Premchands or Nirmal Vermas. A substantial contemporary literary canon seems absent—one that truly captures the zeitgeist through imagination and craft.

And with the focus increasingly on politics rather than prose, assessing literary merit is becoming tougher, according to novelist and DU Hindi professor Pravin Kumar.

“A highly political reading of texts is being done,” he said. “Form and craft are not being interpreted the way earlier critics used to.”

Two very different streams are shaping Hindi literature currently. On one side are fierce new DBA voices who are challenging the status quo. On the other is a pulp invasion, advancing from footpath stalls to reputed publishers and even university syllabi.

Also Read: Who’s the Chetan Bhagat of Hindi fiction? New wave of celebrity writers, punchy plots, Reels

DBA jolt to Hindi literature

The impact of the rise of Dalit, Bahujan, and tribal voices in Hindi literature is palpable on campuses.

At Delhi University’s Hindi Department, for instance, of the roughly 200 PhD students, over 50 are focusing their research on Dalit, women, and tribal narratives. Their theses cover topics like tribal identity in 21st-century Hindi literature, human values in Dalit women’s stories, and comparative studies of women’s consciousness in Dalit literature.

This shift started with Omprakash Valmiki’s groundbreaking Joothan, the first literary Dalit autobiography in Hindi. Academic conferences, literary awards, special magazine issues, translations into multiple languages, and even documentaries followed its publication. Valmiki’s subsequent works, such as the short story collections Salaam and Ghuspethiye, and Safai Devata, a history of the Valmiki community, also shaped discussions on Dalit writing.

Valmiki’s influence opened the door for a new genre—the Dalit literary memoir. Critically acclaimed works like Tiraskrit (Spurned, 2002) by Surajpal Chauhan, Mera Bachpan Mere Kandhon Par (My Childhood on My Shoulders, 2009) by Sheoraj Singh Bechain, and Tulsiram’s two-part autobiography Murdahiya (Mortuary, 2010) and Manikarnika (2016) are now considered classics.

In Murdahiya, Tulsiram, a former JNU professor, recalls how, at the age of 5, Brahmins in his village refused to read letters from his family, who worked in Kolkata’s mines and mills.

“Fed up with this behaviour, my family took pity on me as the youngest child and sent me to school so I could read the letters myself,” he wrote.

Earlier, there was class-based criticism (of books); now there is caste-based criticism. This is a huge change

-Ramashankar Kushwaha, associate professor of Hindi at Dyal Singh College

Dalit women writers like Rajat Rani Meenu, Anita Bharti, and Tara Parmar have also challenged conventional notions of feminism with their intersectional perspectives. Many of these DBA authors’ works have made it into the syllabi and reading lists of Indian universities.

This new literary space emerged after the Mandal Commission recommendations in 1990, which opened universities to marginalised communities and began influencing the traditional curriculum.

“With the arrival of these discourses, not only literature but also the curriculum was democratised,” said Sheoraj Singh Bechain. He added that Dalit and tribal writers often brought their lived experiences into their work, adding a new layer of realism to literature.

“Aakhir kab tak kalpana likhi jati (How long will we keep writing fantasies)?” he asked.

However, since the early 2000s, there have been few additions to the Hindi curriculum. Most syllabi still rely heavily on traditional literature, and while university libraries may stock the latest Hindi magazines, they rarely acquire new books. The shelves remain dominated by classics like Maila Anchal by Phanishwar Nath Renu, Godaan by Premchand, and Raag Darbari by Shrilal Shukla.

Research in Hindi has also stagnated. A review of research topics at Delhi University’s Hindi Department from 1951 to 2018 shows repetitive themes—like the 2000 and 2005 PhDs on ‘Imagery in the Ethical Poetry of the Ritikāl Period’ or the similar studies on existentialism in Nirmal Verma’s literature in 2001 and 2005.

“This is not a healthy situation for Hindi,” said a PhD student from the department regretfully.

There’s widespread consensus that, overall, authors today are not experimenting as boldly with craft—barring exceptions like Ret Samadhi (Tomb of Sand, 2018) by Geetanjali Shree.

Golden age still rules

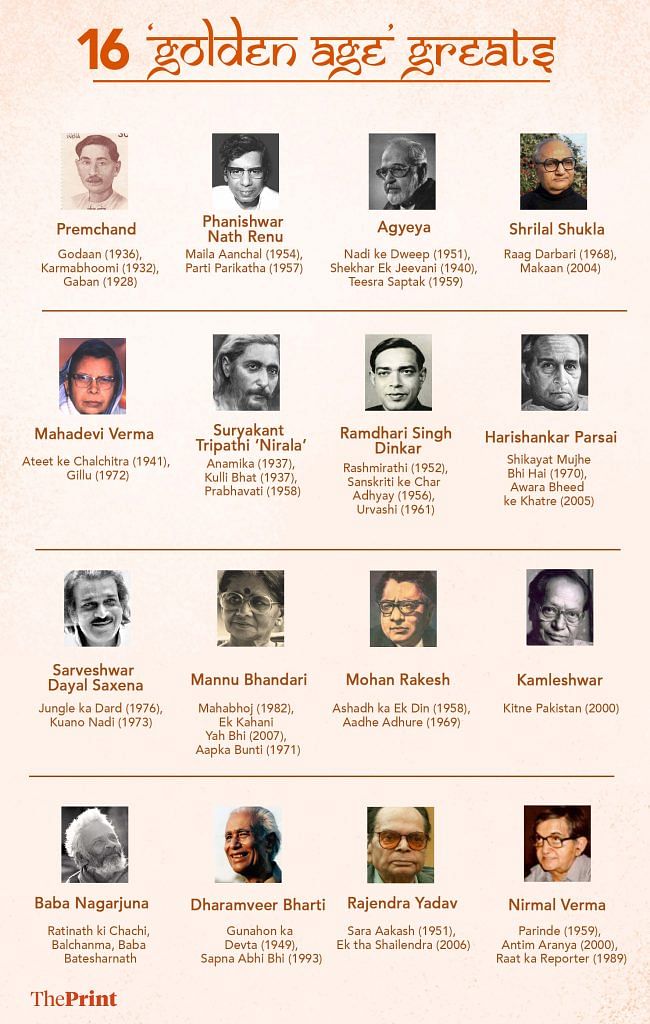

Despite the overhauling of the Hindi literary ecosystem, no contemporary writers wield an influence similar to the giants of the past—Premchand, Nirmal Verma, Dharamveer Bharti, Agyeya, Nagarjuna, Mahadevi Verma, Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Harishankar Parsai, Namvar Singh, and Sarveshwar Dayal Saxena.

For many, these represent the golden age of Hindi literature, arguably at its peak in the mid-20th century. The new crop of writers has yet to fill the void.

“It is a bitter truth that these people were the last generation of big Hindi writers. The impact was such that readers had personal stories of their writers,” said Satyanand Nirupam, editorial director of Hindi publishing house Rajkamal Prakashan.

In Hindi literary circles, it’s widely believed that books such as Premchand’s Godaan, written in 1936, remain relevant today because the issues they address—like the plight of farmers—are still pressing. However, new writers seem more prone to following fleeting trends.

“Premchand wrote with a big vision, but today’s literature is stuck in the moment,” said Prabhat Ranjan, a writer and professor of Hindi at Zakir Hussain College, Delhi University. “More is being written on current topics, but it lacks the same depth. That’s why noted writers are not emerging in Hindi.”

This seems to hold true in the Hindi department of Delhi’s Dyal Singh College, where a small room has a line-up of black-and-white photographs of Hindi writers. This Hall of Fame features the Golden Age greats, as well as later Dalit doyens like Valmiki and Tulsiram—but after them, there are decades of empty space on the walls.

Up until the 1980s or so, Hindi departments were epicentres of the literary scene. They produced luminaries such as Namvar Singh, the esteemed literary critic who founded the Bhasha Kendra at JNU, Dharamvir Bharti, author and editor of the once-influential literary journal Dharmyug, and Mohan Rakesh, a pioneer of the 1950s’ Nayi Kahani (New Story) movement.

But today, the influence of Hindi departments has faded. They’ve become largely powerless within the campus, clinging to old practices and modes of thinking.

“The Hindi department used to pave the way for students to progress in Hindi. But now this is not happening,” said Ranjan.

Poverty of form?

In 1936, when Premchand’s last novel Godaan was published, his style fascinated readers. He used humour and irony to highlight the injustices of rural life and wove in local legends to add depth and cultural context.

Other important Hindi writers had their own USPs. Bhisham Sahni’s writing was emotionally charged, poetic, and introspective; Rajendra Yadav experimented with philosophical and ‘avant-garde’ themes. Nirmal Verma’s lyrical prose explored human relationships in the context of modernism.

These writers became great because they developed their own distinctive styles and weren’t afraid to test boundaries. More recently, Kamleshwar’s Kitne Pakistan (How Many Pakistans, 2000), a novel about Partition and communalism, blends allegory with realism, while Uday Prakash’s novella Peelee Chhatri Wali Ladki (The Girl With the Yellow Umbrella, 2001), often described as a feminist work, is known for its accessible yet vivid style.

No one is in a position to give a new social philosophy. Everyone wants to write in brief. Frivolous poems have increased, and most are about love

-Anamika, Sahitya Akademi Award-winning poet

But there’s widespread consensus that, overall, authors today are not experimenting as boldly with craft—barring exceptions like Ret Samadhi (Tomb of Sand; 2018) by Geetanjali Shree, who won the International Booker Prize in 2022 for her non-linear exploration of an elderly woman’s life and Partition memories.

“This is the era of discourse-based writing. More emphasis is being given to reality, due to which experiments are not being done. But style is a medium, and the real substance is content,” said literary critic Virendra Yadav.

A similar shift is evident in poetry.

There was a time when poets were seen as the voices of the nation. Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s lyrical yet rousing compositions like Rashmirathi, with its mythological and political themes, are still quoted often. There’s also a resurgence of interest in Nagarjuna, the “people’s poet” who combined Leftist thought with symbolism.

“Officers of the police department, listen to me, the public has even kicked Hitler and Mussolini,” he wrote in Police Officer.

But today, a common lament is that few poets challenge power with forceful language.

“The poetic quality in poetry has reduced. The tendency of self-indulgence has increased a lot, as poets are growing more distant from life and society. The writing no longer has the impact it once did,” said poet Sudhanshu Firdaus, awarded the Bharat Bhushan Award in 2021.

It’s also becoming increasingly difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff. Technology has made it easy to write and publish immediately, bypassing the rigorous editorial processes of the past.

“I started writing my first novel Khule Gagan ke Laal Sitare (Red Stars in the Open Sky) in 1992 and it came out in 2000. Earlier, one had to work very hard to get published,” recalled noted novelist Madhu Kankariya.

While the democratisation of content has given more voices a platform, some writers complain it’s also led to a glut of shallow work.

“No writer has time to stop and look,” rued Anamika, the first woman poet to win a Sahitya Akademi Award in 2021. “No one is in a position to give a new social philosophy. Everyone wants to write in brief. Frivolous poems have increased, and most are about love.”

Despite these trends, some newer writers are using their art as a form of resistance and exploring the burning questions of the day.

While senior Left-leaning authors such as Akhilesh have criticised the weak opposition to Hindutva within Hindi literature, some new writers are bucking the trend.

New voices of resistance—and a pulp wave

Two very different streams are shaping contemporary Hindi literature. On one side are fierce new Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi voices who are breaking ground with stories and poems that challenge the status quo. On the other is a steady pulp invasion, advancing from footpath stalls to reputed publishers and even university syllabi, once the domain of serious, weighty prose.

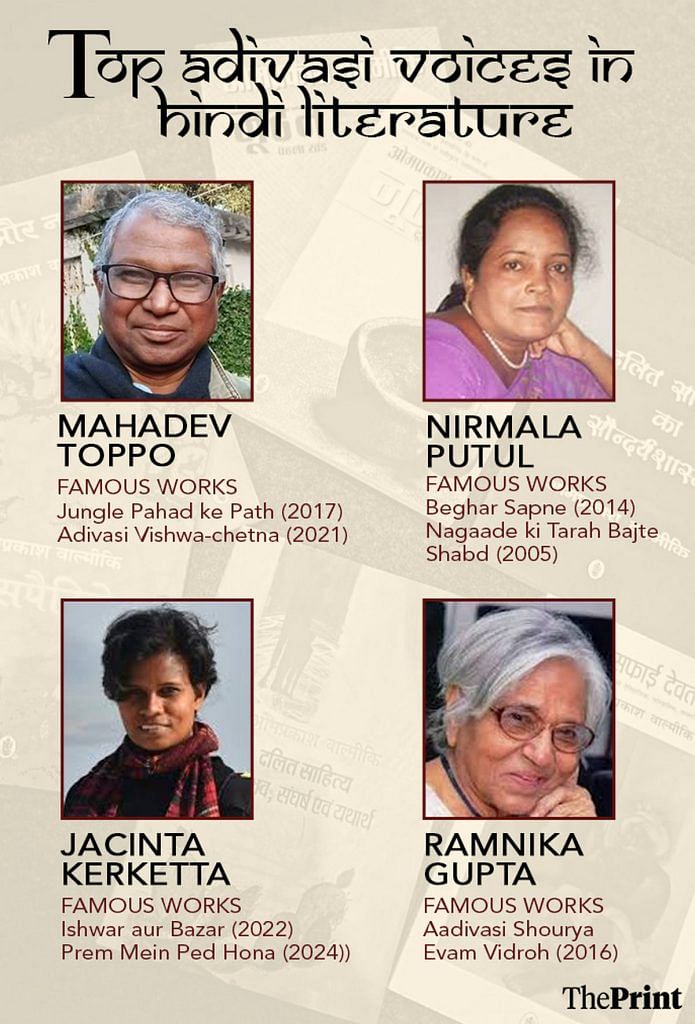

In the first stream, writers such as Shyam Nirmohi and Jacinta Kerketta are using personal experiences and observations to confront political and social issues.

“This journey of sorrow is still alive, the division between humans is still alive,” writes Nirmohi, a young Dalit poet from Rajasthan, in Santaap Ka Safar (Journey of Suffering). His collection Ret par Kashtiyan (Boats on Sand, 2022) is a “combination of experience and contemplation” according to Jaiprakash Kardam, a senior Dalit writer and former director of Central Hindi Training Institute.

Then there’s Jacinta Kerketta, an Adivasi poet from Jharkhand, who turned down a literary prize last year in protest against the condition of tribals.

“Pet dogs are less likely to be killed than strays, that’s because they wag their tails with all their strength,” she wrote in a poem in her acclaimed collection Ishwar aur Bazaar (God and the Market, 2022), which has been translated into multiple languages, including German, Italian, and French.

But it’s not only Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi writers who are making an impact in the sphere of resistance literature.

While senior Left-leaning authors such as Akhilesh have criticised the weak opposition to Hindutva within Hindi literature—arguing that even if there’s mental resistance against communalism, it rarely translates into literary expression—some new writers are bucking the trend.

For instance, Chandan Pandey, an emerging star in Hindi literary fiction, has tackled contemporary sociopolitical controversies head-on. In the slim Vaidhanik Galp (Legal Fiction, 2020), he seamlessly weaves a critique of love jihad, communalism, caste, and corruption into a fast-paced plot. Author Amitava Kumar even likened the English translation to “Camus in the cow belt”.

In his latest novel Keertigaan (Songs of Glory, 2022), Pandey explores the roots of communal mob lynching and the spread of societal madness. “Only the person whose house it (the mob) reaches can know their strength. Many of them are unfortunately the remaining future of this country,” reads one passage.

Another emerging writer in Hindi is Pravin Kumar, whose debut novel Amar Desva (Immortal Land, 2021) stitches together a compelling story about a labyrinthine system, citizenship, and what is real or not in the time of Covid.

“In this novel, a voice has been raised about the rights of ordinary citizens,” said Apoorvanand, a Hindi professor at Delhi University.

In poetry, Sudhanshu Firdaus has gained recognition for blending personal reflection with universal themes like social justice and the human psyche.

This is the era of discourse-based writing. More emphasis is being given to reality, due to which experiments are not being done. But style is a medium, and the real substance is content

-Virendra Yadav, literary critic

“These slanting lines, the boundaries formed by them, we call them a country, where souls yearn for freedom. If not prisons, then what else are they?” he writes in In Mulk Hai Ya Maqtal (Country or Slaughterhouse).

While these writers are revitalising Hindi literature, albeit on a small scale, another trend is causing a heated high culture vs low culture debate—the newly elevated status of commercial fiction.

About ten years ago, masala-fiction authors like Gulshan Nanda and Surendra Mohan Pathak—known for their fast-paced detective novels—were added to Delhi University’s Hindi curriculum under the banner of Lokpriya Sahitya (Popular Literature).

“No one opposed lugadi (pulp) literature to be included in the university syllabus. No one had even thought that such a thing would happen,” said DU professor Ranjan.

But even earlier, writers like Nanda, Pathak, Ved Prakash Sharma had their books snapped up on railway platforms and bus stands while more “serious” authors like Nirala and Bhuwaneshwar struggled financially, dying in poverty. Nanda’s novels were even adapted into Hindi films in the 1960s and 1970s, including Kati Patang, Sharmeelee, and Daag.

What’s different now is that even ‘respectable’ publishers are jumping in to leverage the mass appeal of ‘lightweight’ writing, long looked down upon by the gatekeepers of Hindi literature.

What Chetan Bhagat did for English writing, novelists like Divya Prakash Dubey, Nilotpal Mrinal, and Anurag Pathak are doing for Hindi. They’re speaking to Gen-Z with their lighthearted prose on travel, aspiration, and heartbreak.

“The triumph of populism has ensured that the word buddhijivi (intellectual) is now often thrown as a derogatory usage,” bilingual writer Ashutosh Bhardwaj pointed out.

Wobbling support structures

The qualitative drift in Hindi literature is closely tied to the slow decay of the pillars that once supported it.

Cultural institutions—such as Sahitya Akademi, Bharatiya Jnanpith, Rajya Sabha Hindi Samiti, and Central Hindi Institute—which bolstered Hindi writers from the 1950s onwards, are now flailing.

A telling example is the controversy surrounding the 2022 Sahitya Akademi Award. Despite 11 strong contenders, including heavyweights like Mrinal Pande, Chandan Pandey, and Geetanjali Shree, the award went to social scientist and academic Badri Narayan. What especially raised questions about transparency was that Shree’s Ret Samadhi, which had won the International Booker Prize, was overlooked by the Sahitya Akademi.

This is not the time to give literature a reprieve, but to expect it to be more moral and more active

-Ashok Vajpeyi, author

Important Hindi poets and writers like Nirala, Muktibodh, Phanishwarnath Renu, and Rajendra Yadav never received the Sahitya Akademi Award, while “long forgotten authors” were honoured, poet Krishna Kalpit wrote in Navbharat Times.

Questions about the autonomy of these institutions are now being raised.

Last year, poet Ashok Vajpeyi excoriated the Akademi for its misplaced priorities, noting that it organises cleanliness programmes but doesn’t hold condolence meetings for murdered intellectuals.

Vajpeyi, who returned his Sahitya Akademi award in 2015 to protest attacks on freedom of expression, also wrote last year that literature must speak truth to power.

“This is an extraordinary time, a moment of crisis for Indian civilisation and expecting anything less from literature at this time would be like underestimating its importance and influence,” he said. “This is not the time to give literature a reprieve, but to expect it to be more moral and more active.”

But the diminished state of Hindi literature isn’t just about floundering institutions. It’s also about a parallel erosion in robust literary criticism and the once-vibrant literary magazine culture.

Also Read: Harry Potter sealed the defeat of Hindi books for children. But a new ‘pitara’ looks promising

Shrinking space for criticism

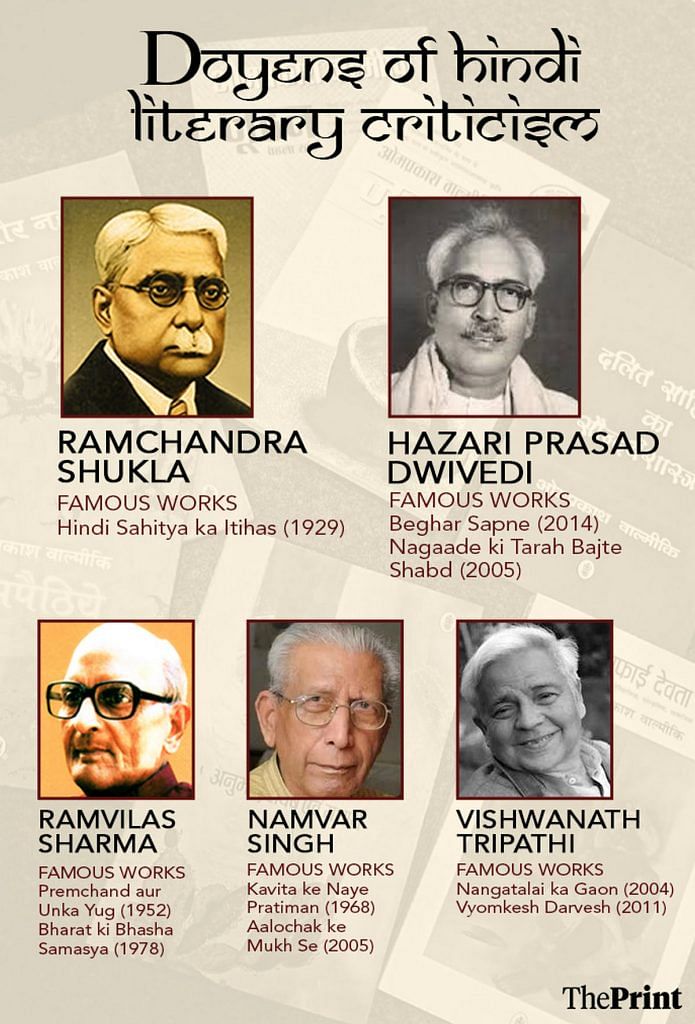

From titans like Acharya Ramchandra Shukla and Ramvilas Sharma to Namvar Singh, and Vishwanath Tripathi, Hindi literature has a rich tradition of criticism. But now, it’s a shadow of its former self.

“Earlier, critics did deep ideological and theoretical work. In today’s criticism, that’s not being done,” said Virendra Yadav, a literary critic.

Literary circles still swap stories about Manohar Shyam Joshi’s scathing take-down of Raghuvir Sahay’s 1979 Macbeth translation Barnam Van. Or how in the 1960s, eminent poet Muktibodh compared Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s epic mythological poem Urvashi to a loudspeaker blaring in a bedroom.

“The meaning of criticism is to point out the merits and demerits. Earlier, such risks were taken but today people get angry if demerits are pointed out, so mostly only good things are written,” claimed Prabhat Ranjan, author of Paaltu Bohemian, a book about Manohar Shyam Joshi.

Even in literary magazines, polite reviews have largely replaced critical analysis—which author Pravin Kumar pegged to a decline in reading and writing, as well as a tendency to prioritise social and political content over literary merit.

“Critics presently are not able to interpret the text creatively, due to which criticism is becoming flat,” he said.

There’s been an ideological shift too. Earlier, many prominent literary critics viewed texts through the lens of Marxism, but after the 1990s this tradition has diminished. Political correctness, especially around caste, has also stifled critiques, hinted several writers.

“Earlier there was class-based criticism; now there is caste-based criticism. This is a huge change,” said Ramashankar Kushwaha, associate professor of Hindi at Dyal Singh College.

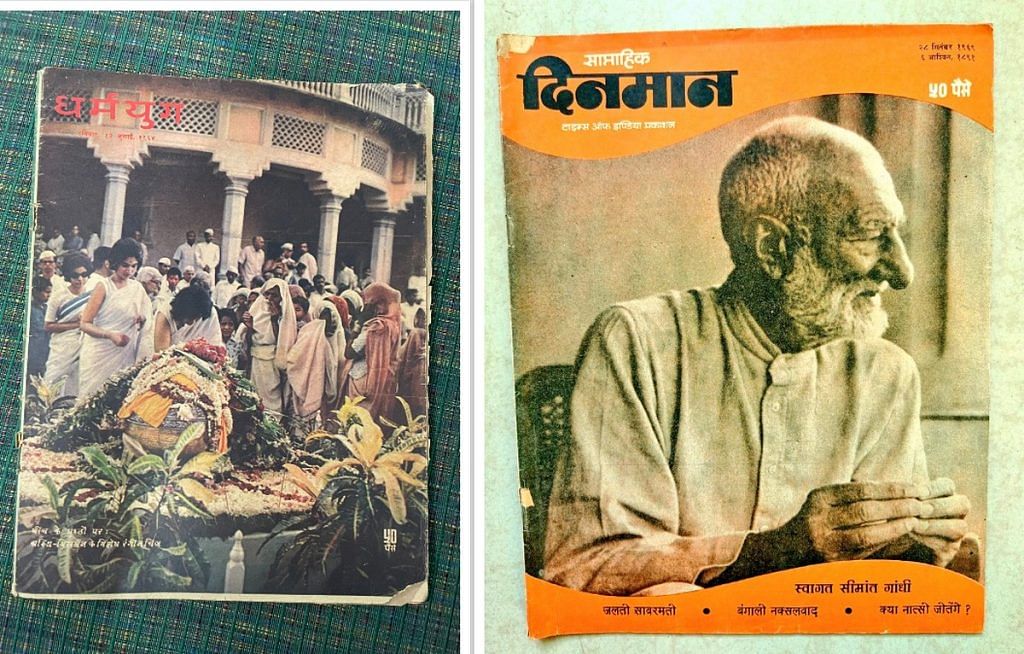

The decline of literary magazines has also shrunk the space for both criticism and new authors. Many prestigious magazines have shut down one after the other, including Dharmyug, Dinman, and Kadambini. The latest casualty was Pehal, which closed in 2021 after nearly 50 years in circulation. In 2020, it was Dharmyug, which was the first to publish stories by legendary writer Shivani and serialised Mohan Rakesh’s cult play Aadhe Adhure. It also introduced the works of Mrinal Pande and Rajesh Joshi.

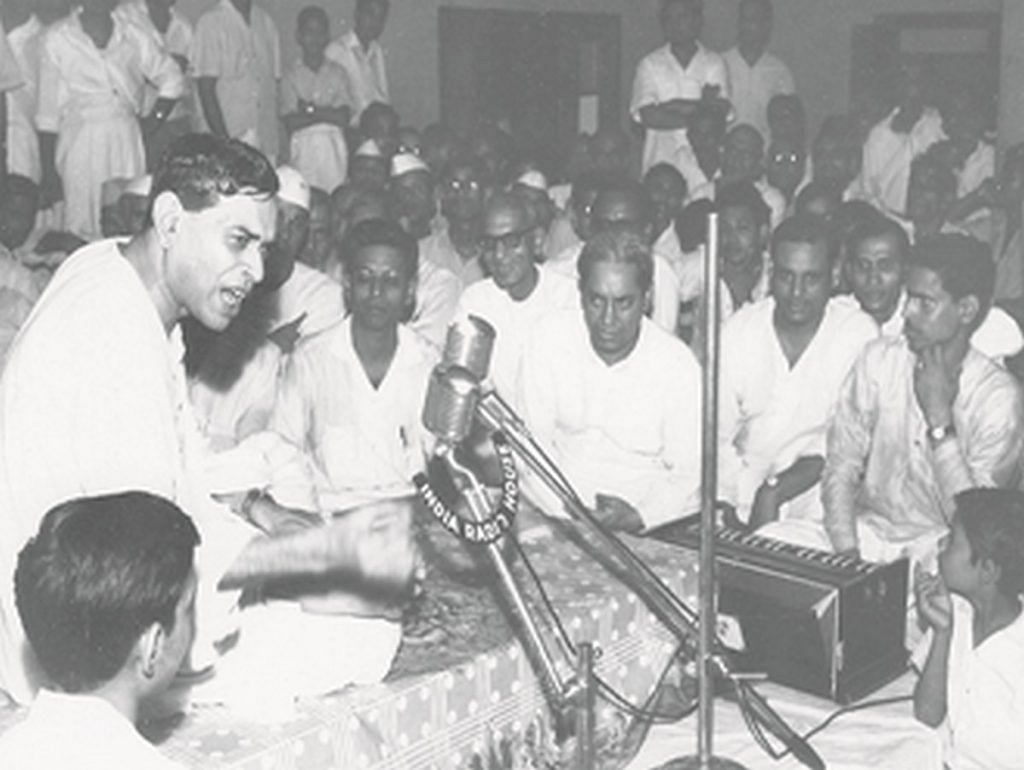

Newspapers no longer devote full pages to literature and culture, and poetry programmes like Radio Varta have all but disappeared.

“After 1990, all the bridges (to bring literature to the public) started collapsing and new bridges were not developed,” said Satyanand Nirupam, editorial director of Rajkamal Prakashan, in his Daryaganj office. He linked this decline to the emergence of a new, multicultural middle class after economic liberalisation in the 1990s.

Only a handful of literary magazines have survived the churn—Hans, Vanmali, Kathadesh, Vagarth, Tadbhav, Aalochana, and Nayi Dhara.

Nayi Dhara has been continuously in print since 1950 and has over 45,000 subscribers. “Its online edition is now creating a digital repository of all the issues [published] over three-quarters of a century,” said editor Arti Jain.

Run by Rajkamal Prakashan, the seven-decade-old Aalochana recently moved online, while Hans—originally started by Premchand in 1930—was revived in 1986 under Rajendra Yadav.

Hans, especially, has given opportunities to many new writers even in recent decades. It was the first to publish Geetanjali Shree’s story Belpatra, parts of Uday Prakash’s Peeli Chhatri Wali Ladki, and even excerpts of Valmiki’s Joothan.

In 1999, an entire issue of Hans was dedicated to the writings of minorities. And in 2003, a special issue on the present and future of Indian Muslims was published.

“Hans brought Dalit writing to the centre of mainstream national debate,” said Sheoraj Singh Bechain.

Now, squeamishness around “controversial” topics has increased, according to some writers.

Shahadat’s 2016 story Jumma, for example, was rejected 18 times before being published in Hans in 2018. The story, which critiques a maulana’s hypocrisy about homosexuality, was considered too incendiary by magazines like Vagarth, Kathadesh, and Pakhi, he told ThePrint.

“Hindi literature is avoiding taking risks now,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

In this entire article, the story writer Gyanranjan and the ‘Pahal’ published under his editorship were forgotten.

It’s good to know that Hindi has a literature. Hope it has poetry too.