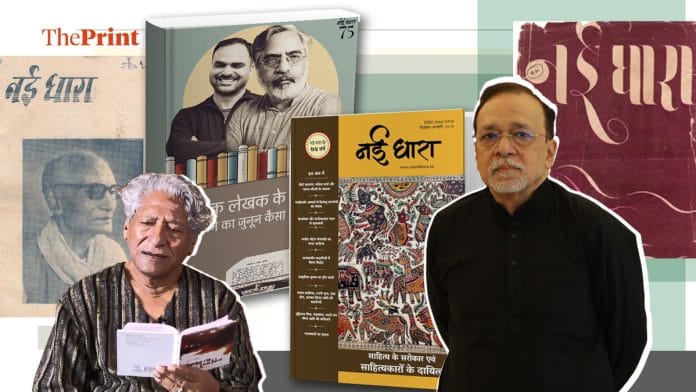

New Delhi: When Allahabad ruled the Hindi literary scene in the 1950s, a bimonthly magazine from Bihar arrived with a gust of new ideas and voices. Nayi Dhara was a disruptor not just for its substance but its stature, publishing the most influential names of the time—Harivansh Rai Bachchan, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Mahadevi Verma, Amrita Pritam.

Seventy-five years after its heady launch by Udaya Raj Singh, a scion of the wealthy Surajpura zamindari estate, Nayi Dhara is getting a do-over for the digital age. It’s a pet project of his son Pramath Raj Sinha, one of the founders of the elite Ashoka University and the founding dean of Indian School of Business.

“When I can build institutions, I can revive my legacy too,” said Sinha proudly at his Delhi residence. “The practice of reading and writing has completely changed. Nayi Dhara is trying to play a role in a new avatar for Hindi literature. Today, when there seems to be an environment where people are not interested in Hindi literature, it has become a platform for those who are.”

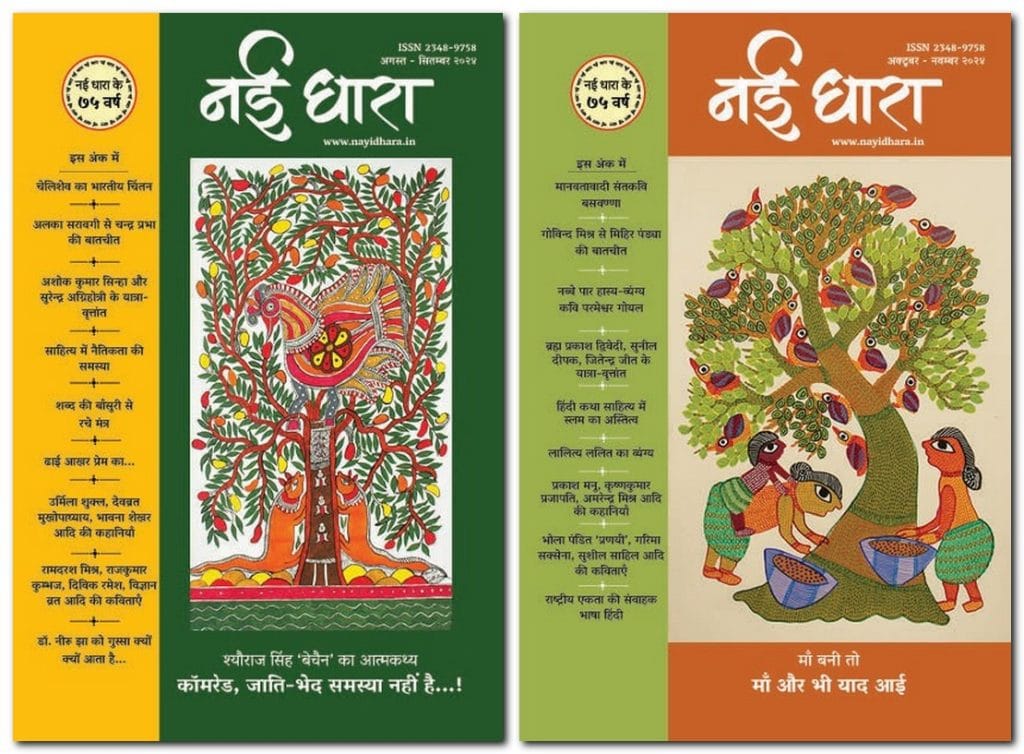

For 60-year-old Sinha, the old-world rhythms of Nayi Dhara—which means ‘new currents’— were increasingly out of step with the younger generations it needed to reach. So he started doing what he’s known for as an educationist—transforming and modernising it. Under his watch, the magazine has digitised its archives, introduced video and audio formats, and built a new presence on social media where the rhymes of the Hindi greats now show up as Reels. It’s also experimenting with musical collabs, like the ‘Nayi Dhara Bhakha’ series, where folk songs meet literary deconstruction. The latest push is the first Hindi writers’ residency at the historic Suryapura House in Patna.

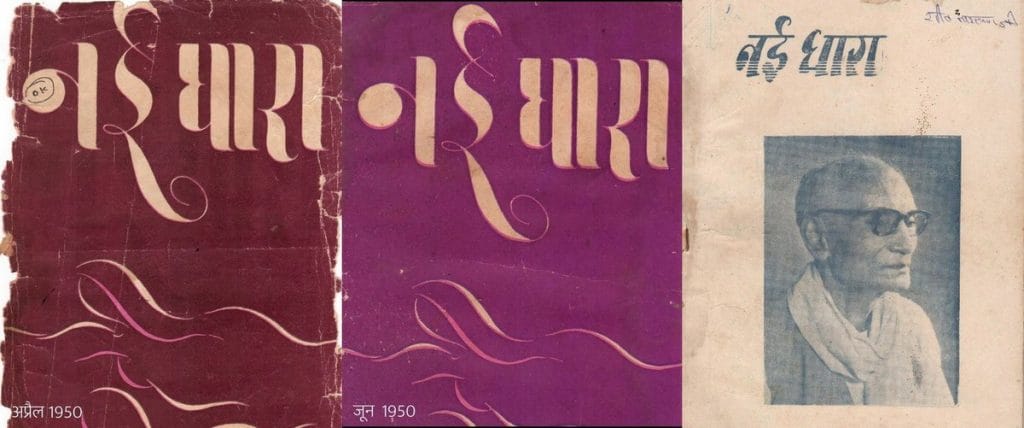

In a way, Nayi Dhara has come full circle in its quest to challenge the status quo. When it was launched in April 1950, the idea was to shake up the world of print, specifically the elite, insular literary circles of Allahabad. Its reputation grew fast. It took risks with form and became a place where both towering names and unknown writers could be seen side by side.

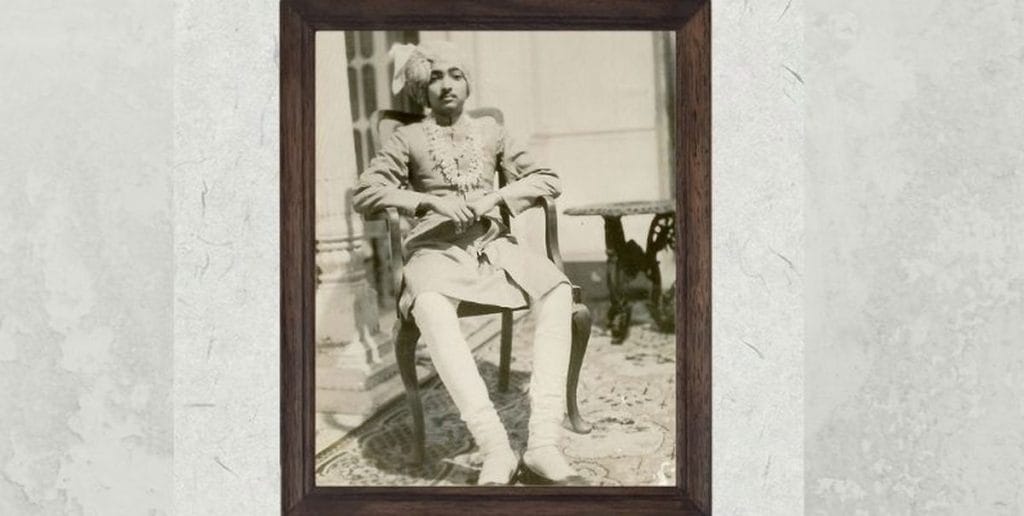

But underneath, it always had a solid foundation. Three generations of the founding family have carved a niche in Hindi literature, beginning with Sinha’s grandfather Raja Radhika Raman Prasad Singh, one of the leading lights of the Marxist-influenced pragativaad (progressive) movement of the 1930s and ‘40s—despite being from a zamindar family.

My father thought everything would stop after him, but perhaps he didn’t realise the deep impression the house’s atmosphere had left on me since childhood

-Pramath Raj Sinha

Even today, the magazine is banking on its roots, with the slogan “1950 se sahitya ki ananya dharohar” (A unique literary legacy since 1950). Where giants like Dharmyug, Dinman and Kadambini shut down as Hindi magazine culture shrank, Nayi Dhara has stayed continuously in print for 75 years. At the same time, it has adopted new media more aggressively than other surviving stalwarts like Hans, Vanmali, Kathadesh, Vagarth, Tadbhav, and Aalochana.

“With our digital presence, the audience knows and engages with our work on a daily basis. This level of change in five years is remarkable in itself,” said Arti Jain, digital editor of Nayi Dhara.

For many writers, Nayi Dhara was an important income stream. “I am forced by some financial reasons to request that if you accept the article, please send me its remuneration in advance,” read a 1967 letter to Udaya Raj Singh from the eminent poet Raghuvir Sahay.

Also Read: Is Hindi literature adapting to survive? It has more Chetan Bhagats than Omprakash Valmikis

How Patna took on Allahabad

From its very first issue, Nayi Dhara signalled it was already in the big league. It included Priye shesh bahut hai raat abhi mat jao (My love there is still a lot of night left don’t go now) by Harivansh Rai Bachchan, published that year in the acclaimed collection Milan Yamini. Bachchan would later say this poem, written in 1949, was one of his favourites.

Soon, the likes of Dinkar, Nirala, and Maithili Sharan Gupt were regulars on its pages.

In 1968, Dinkar poured his heart out to Udaya Raj Singh about his son Ramsevak’s illness.

“I am passing my days in great distress. Ramsevak is terribly ill. There is no cure in allopathy. Ayurveda also did not help. Now I have resorted to homeopathy. Only God knows what is going to happen,” Dinkar wrote. In 1968, he sent a note of congratulations: “The magazine is coming out very well.”

For many writers, Nayi Dhara was an important income stream.

I am forced by some financial reasons to request that if you accept the article, please send me its remuneration in advance,” read a 1967 letter from poet Raghuvir Sahay, who would go on to win the 1984 Sahitya Akademi Award for his poetry collection Log Bhool Gaye Hain.

Even before it hit the presses, there was buzz around the magazine, largely due to the goodwill amassed by Udaya Raj Singh and founding editor Rambriksh Benipuri, a Socialist and noted writer in his own right.

In February 1950, two months before the inaugural issue, the renowned novelist Hazari Prasad Dwivedi sent a letter from Shantiniketan to Benipuri, pledging his support.

“When you edit it, it will undoubtedly have high value. You issue a magazine and I do not cooperate with it—this cannot happen,” he wrote.

Bachchan too espoused his allegiance in a letter that same month: “Jabhi koi achhi cheez likhunga, Nayi Dhara ke liye reserve kr lunga (Whenever I write something good, I will reserve it for Nayi Dhara).

Our idea was clear that we will neither look Left nor Right—we will look at the quality of work and give opportunities to new writers

-Shiv Narayan, Nayi Dhara editor

When Nayi Dhara launched in Patna, it was a glittering affair. Then Bihar Chief Minister Sri Krishna Singh did the honours, while the guests included literary luminaries such as Dinkar and Renu.

Udaya Raj Singh’s patronage of writers started with his desire to promote his own father’s work. Raja Radhika Raman Prasad Singh, known as Shaili Samrat (King of Style), was hailed as one of the first writers of Hindi short stories, but his work was not easily available. Udaya wanted to rectify this.

“Many people had this complaint,” said Pramath Sinha. “That’s why my father started the press.” It was Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna, a close friend, who tipped off Udaya about a press for sale in Allahabad. He bought it and moved it to Patna.

“My father started a second-hand press named Ashok. Then Shiv Pujan Sahay advised him to start a magazine. This is how Nayi Dhara was born in 1950,” said Sinha.

Initially, Sahay, a Bhojpuri and Hindi writer, was meant to be the first editor, but he got pulled into a government project. And so the job went to Benipuri.

At the time, the Parimal literary movement in Allahabad was a dominant force that supported local magazines, with writers like Dharamvir Bharti—who later helmed Dharmayug— defining the scene. Benipuri wanted to start something equally influential from Patna.

“Benipuri was a big name that time. He wanted to set up a magazine of the Allahabad level from Patna,” said Shiv Narayan, who has been associated with Nayi Dhara for 36 years and is now its editor.

But unlike other Hindi magazines, which wore their ideologies on their sleeves, Nayi Dhara tried to avoid political pigeonholing.

“Our idea was clear that we will neither look Left nor Right—we will look at the quality of work and give opportunities to new writers,” said Narayan.

Even so, not everyone bought the image of neutrality. Hindi writer and professor Prabhat Ranjan said it was viewed as a magazine owned by a “capitalist”, a label that hurt its literary cachet.

“Without any competition, it has remained in the publishing world and has been paying good remuneration to Hindi writers but this magazine does not have the same impact as magazines like Hans and Sarika,” he said.

Narayan rejects these claims.

“This magazine has worked beyond ideology and made both socialist Rambriksh Benipuri and communist Vijay Mohan Singh its editors,” he said.

Nayi Dhara’s online footprint is growing, with about 158,000 subscribers across social media platforms today, compared to only 12,000 in 2021. Jain says it’s all “organic”.

Residency, Reels, reach

Poet Krishna Kalpit’s Facebook timeline was flooded with congratulations last month. He’d just been selected for Nayi Dhara’s Sahityik Niwas Karyakram (literary writer’s residency), which he called the first initiative of its kind for Hindi writers.

“In this six-week residency program, writers can complete their unfinished manuscripts,” wrote Kalpit in his Facebook post. On 1 June, he and another writer, Shivangi Goyal, started their six-week stint in the stately white-walled Suryapura House in Patna, once home to Raja Radhika Raman Prasad Singh.

For years, writers had been requesting Pramath Sinha to create a space where they could work in peace. The residency, he said, is his gift to the Hindi literary community.

“In our 75th year, we have created this Writers Residency, bringing together established and emerging writers to complete their work,” he said.

It’s one strand of his broader plan to overhaul Nayi Dhara. Another is marrying legacy with digital ambition.

Its online footprint is growing, with approximately 158,000 subscribers across social media platforms today, compared to only 12,000 in 2021, according to Jain. It has 87,000 followers on Facebook, 1,053 on X, and over 40,000 on Instagram. Its YouTube channel, with 16,000 subscribers, hosts interviews, performances, and literary explainers.

“We are presenting literature in audio and video forms. These include interviews, podcasts, and a poem every day—presented with good diction,” said Sinha.

On Instagram, poems are posted as easily shareable memes. A recent one was a short, relatively obscure verse by Nirmala Garg:

Main apni sabse acchhi kavita

kaagaz par nahin likhoongi—

patte par.

Ped prakashak se zyada udaar

zyada samajhdaar hota hai

(I will not write my best poem on paper—

but on a leaf.

A tree is more generous

and more understanding than a publisher.)

Some commenters praised its punch, while another asked where the full version could be found. The Nayi Dhara handle replied: “Itni hi hai” (It’s just this).

While the print edition is based in Patna, the social media arm is run from Delhi by digital editor Arti Jain, who oversees a team of 10. Her brief is to make Hindi accessible to an online generation with fast-changing tastes.

“Our journey is like a marathon. We have been here for a long time. We offer a good mix of different generations, ideas, and style of writing,” she said.

Jain has reimagined how Hindi literature appears online, with multiple content verticals. In the Pratidin Ek Kavita, a poem is recited each day, matched with evocative visuals. The poets range from Jaun Elia and Ashok Vajpeyi to Ramanath Awasthi and Vandana Mishra.

In the Ekal series, theatre actors read or perform literary works. Himani Shivpuri appeared as Mitro from Krishna Sobti’s Mitro Marjani, Virendra Saxena did an emotive Hanoosh by Bhisham Sahni, and Rajendra Gupta recited from Mohan Rakesh’s Ashadh Ka Ek Din.

Then there’s Panno se Parde Tak, which spotlights the link between literature and cinema. A 25 May Instagram Reel highlighted Nida Fazli’s “Tere bagair jahan mein koi kami si thi”, sung by Mohammad Rafi in Aap To Aise Na The.

Other series include Kahani Train, narrated by Jain, 365 Days, 365 Books, and Nayi Dhara Samvaad, featuring discussions with authors, from Booker Prize winner Getanjali Shree to journalist Mrinal Pande.

The Nayi Dhara website claims the magazine has published more than 10,000 articles and has a strong connection with 3,000 writers.

“Through video interviews, podcasts and various attractive programs, Nayi Dhara website makes Hindi literature available to you at a click,” it adds.

The digital push is bolstered by offline events, including writing workshops led by poets like Anamika, the annual literature festival Udayotsava, and folk music series Bhakha.

One performance had Varanasi-based folk singer Mannu Yadav performing at Delhi’s India International Centre.

“On one hand folk songs connect us to historical things; on the other, even the biggest things, biggest philosophies are explained by describing the things around us,” says the video caption

Jain said this unbroken continuum between folk dialects and formal language was captured by none other than Kabir when he wrote: Sanskrit hai koop jal, bhakha behta neer (Sanskrit is water in a well, folk language is running water).

It is this complete and connected ecosystem of literature, music, and the arts that Pramath Sinha wants to recreate, not just Nayi Dhara.

“It has been integral to our culture and history. We are promoting the folk music of North India and are conducting a program called Bhakha, a style in which Kabir wrote,” said Sinha, whose drawing room has a sitar taking pride of place.

Jain said Nayi Dhara has spent the last five years finding new ways to engage people in their own language—and the growth has been totally organic.

The revival, she added, was both a passion and an emotional project for Pramath Sinha: “It got a fresh breath of energy from him.”

The raison d’etre of Nayi Dhara was never vanity publishing, nor was it meant to be an insular family project. From the beginning, it set out to engage a broader literary culture—across genres, forms, and ideologies.

A family tradition

Growing up in Suryapura House, Pramath Sinha was surrounded by some of the biggest names in Hindi literature.

“Whenever Mahadevi Verma came to Patna for a literary meeting, she always stayed at our house,” he said. “Our home was like a guest house for Hindi writers. My father was fond of all of them. Those were great days.”

As a child, Sinha often attended book launches and sahitya goshthis (literary gatherings) with his father Udaya Raj Singh. He was reluctant at first, but slowly got drawn in.

“It used to feel amazing. The behaviour of the big writers was very simple and humble. Despite being so famous, they used to conduct themselves with humility,” said Sinha.

Many of them were, he recounted, were politically active too, especially during the Emergency. The 1970s also saw the JP movement unfold in Bihar, leading to a groundswell of political activism.

“JP was our role model,” Sinha said. “I saw his Sampoorna Kranti movement very closely and it had a great impact on me.”

During this era, political fault lines ran through his own family’s close circle. Janata Dal leader Mahamaya Prasad Sinha, the fifth Chief Minister of Bihar and a family friend had his campaign material for Lok Sabha elections printed at their family press. There was a quick retaliation.

“Indira Gandhi made my uncle Rajendra Pratap Sinha contest against him. Two camps were formed in my house itself,” he said.

He remembers JP visiting their home with his friend BP Koirala and discussing political strategy, as well as his maternal uncle Bipin Bihari Sinha going underground during the Emergency.

“He was very close to JP. In those days, he used to publish underground bulletins. We had a cyclostyling machine and I used to help,” he said. “All this is seen in books and films now but I have lived through it. People have forgotten those times now—28 years after independence, we got a new freedom.”

Nayi Dhara did not limit itself to literature only but also brought out different genres like theatre, cinema, a Bernard Shaw special issue, and a Samanantar Kahani (parallel story) special issue, which became quite popular. For us, more important than famous names is how well a writer has captured the sentiments of their time

-Shiv Narayan, editor

Through this period of churn, Udaya Raj Singh maintained friendships with politicians but stayed focused on literature. At times, literary salons and musical events overlapped each other.

“During Dussehra in Patna, there was a music conference for three or four days. Writers used to participate and even preside over it. The same people who were seen at literary seminar were now anchoring classical music programmes. It was surprising to see,” Sinha said.

Literature was woven into daily life at home. His elder sister, Manjari Jaruhar, Bihar’s first woman IPS officer, also wrote about Nayi Dhara in her memoir Madam Sir.

“Father’s family had a strong literary tradition, his own father, grandfather, great grandfather were from the world of poetry and literature. Babuji was also a writer and journalist. The first issue of Nayi Dhara magazine came out in April 1950, six months before my birth,” she wrote.

But Jaruhar gravitated toward a career in government service and Sinha toward science. He studied metallurgical engineering at IIT Kanpur, followed by a master’s at the University of Pennsylvania. It was during a stint at McKinsey that he started following in his father’s footsteps in a manner—building institutions from the ground up. He helped set up the Indian School of Business, Ashoka University, Harappa Education, and other ventures. But through it all, he stayed tethered to his literary legacy.

For years, he remained focused on his profession while his father looked after Nayi Dhara, never pressuring his children to carry the mantle.

“My father thought everything would stop after him, but perhaps he didn’t realise the deep impression the house’s atmosphere had left on me since childhood,” Sinha said.

The decision to revive Nayi Dhara began in 2020, during the pandemic—as a way to honour his father’s legacy, and also his mother’s. She had quietly held the magazine together for years.

“Even after Babuji’s demise, Amma kept Nayi Dhara alive for the last 17 years and maintained her interest till the end. So Nayi Dhara is not only the soul of our founder Udaya Raj Singh but also the soul of Amma,” Sinha wrote in an article in October 2021.

His next project is to build an archive of all Hindi writers. By preserving language, we also preserve culture and history,” he said.

Also Read: Uttar Pradesh had a thriving literary culture in the 1980s, but proximity to Delhi killed it

Carrying the current forward

When Udaya Raj Singh died in 2004, it left a vacuum in the Hindi literary world and in Nayi Dhara. Not just readership but even the quality declined, according to some critics.

“Nayi Dhara magazine comes to many houses in Sasaram, Kaimur, and Rohtas but these are the same people who had subscribed during the time of Udaya Raj Singh. They say that now the magazine does not have the same charm anymore,” said Sasaram based historian Shyam Sundar Tiwari.

But to Pramath Sinha, the magazine’s longevity and history mean it can’t be so easily dismissed.

“In these 75 years, the works of the famous writers of those times have been published in it. A very valuable archive of Hindi literature has been created,” he said.

As a boy, the first spark for Udaya Raj Singh came not just from filial devotion and a love of literature, but also from Jawaharlal Nehru.

In 1937, when Nehru came to Ara for a rally, Udaya Raj’s family refused to let him go. In the afternoon, when everyone was having a siesta, he slipped out to the rally ground. A decade later, as a student at Allahabad University, he hoped to start a printing press and inaugurate it with a book on Nehru. But, as he wrote in an article, his first eager early attempt to do so involved shooting off letters to ambassadors abroad without due protocols, thus earning a rebuke from Nehru himself.

In parallel, he was equally determined to bring his father’s work to a wider audience, an endeavour in which he was more successful.

At the Udayaotsav program of Nayi Dhara in December 2024, film historian Ravikant described himself as a great bhakt of Raja Radhika Raman Prasad Singh, born in 1890 to the Surajpur (Surajpura) zamindari family.

“He used to write in Hindustani, and create a unique language by mixing both Sanskritised Hindi and Persianised Urdu. The writers of Bihar have generally been great stylists, and this is because their roots are actually in the village,” said Ravikant.

One of Raja Radhika Raman’s most celebrated stories was Kano Me Kangna, a compact but layered tale about women’s status in society.

In his own writings, Udaya Raj recalled visiting the eminent Hindi poet Surya Kant Tripathi Nirala at his home in Allahabad’s Daraganj on the banks of the Sangam. When he touched Nirala’s feet, the poet looked at him and said: “Oh! You are Radhika Raman’s son! I still remember Kano Me Kangna.”

Pramath Sinha is effusive about his grandfather too.

“When I read that story for the first time, I did not understand it at all. When I read it several times again, it impressed me a lot. His story Ram Rahim is quite famous also. The commentary on the society of that time and the rhythm and language in which he used to write was absolutely amazing. That’s why he is Shaili Samrat,” he said. “We were taught one of his stories during school—Daridra Narayan. It felt very good to know that my grandfather’s story is in my book.”

But the raison d’etre of Nayi Dhara was never vanity publishing, nor was it meant to be an insular family project. From the beginning, it set out to engage a broader literary culture—across genres, forms, and ideologies.

“Nayi Dhara did not limit itself to literature only but also brought out different genres like theatre, cinema, a Bernard Shaw special issue, and a Samanantar Kahani (parallel story) special issue, which became quite popular,” said editor Shiv Narayan. “No one was ever discriminated against on the basis of ideology. For us, more important than famous names is how well a writer has captured the sentiments of their time.”

The magazine publishes six issues annually, with topics selected at the start of the year. Narayan said that “contemporary topics” are prioritised and writers are invited to contribute on that basis.

“We also focus on identity-based writing, which includes issues of tribals and minorities,” he added. The website now has dedicated sections on “feminist discourse” and “Dalit discourse”. In April, Dalit writer and professor Shyoraj Singh Bechain wrote a piece titled Creamy Layer about caste and ‘merit’.

The commitment to platforming new voices has remained a defining feature. Major Hindi writers like Vijay Mohan Singh, Kedarnath Singh, and Govind Mishra all published early work in the magazine.

Pramath Sinha is keen to keep that tradition going.

“So, the name is Nayi Dhara. Even today we keep in mind that we have to take the youth forward—because this generation can take literature forward,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

It is the curse upon Hindus that they will abuse their own motherland, culture, religion and traditions and think that it is being “progressive”.

One unnoticed sample is distortion of the name Ashok as Ashoka. Was the king called अशोक or अशोका? Does any single book of ancient history, even of the fanatical communist variety, write his name as Ashoka ? Over centuries, lakhs and crores of families have named their sons after the name of the illustrious emperor, but was or is any single of them called Ashoka? No , every one named so is अशोक not अशोका. How can they do it? The very pronunciation अशोका sounds ugly and foolish.And this egregious distortion in the very name of the university itself !!! It says a lot.

Pramatha Raj Sinha has done the nation a great service by establishing the Indian School of Business (ISB). The ISB will stand as his legacy in the years to come.

However, the immense goodwill and respect he has enjoyed as the founder of ISB is depleting fast. Why? Because of his patronage of all kinds of anti-India and anti-Hindu elements at Ashoka University. Professors like Aparna Viadik openly teach anti-Hindu hatred filled courses and indoctrinate young minds to hate their own culture, religion and heritage. Foreigners like Christophe Jaffrelot who have made a career out of spewing bile against Hindus and denigrating Hinduism are provided safe shelter. The recent unsavoury episode of Ali Khan Mahmudabad did not exactly bring glory to the university.

Most of the faculty are extreme Left wing and openly pursue an anti-Hindu and anti-India agenda in their teaching and research activities. Some like Mahmudabad are Islamists.

Mr. Sinha must take care not to ruin his reputation by providing shelter to such people at his university.