Shimla: Homeowners in Shimla are obliged to fulfil certain construction requirements—ample parking space, provisions for rainwater harvesting, adequate drainage, and a solar panel. But the New Shimla dream is all about big and bigger homes. Some building bylaws will just have to be bypassed.

“People would rather build bigger homes. So they break the parking lot, get rid of the rainwater harvesting system,” says Shelly Oberoi, matter-of-factly. She is the former councillor of Summer Hill, an upscale neighbourhood of the privileged retired whose foundations were literally shaken by ceaseless rain and a devastating landslide that killed at least 20 people last week.

Himachal Pradesh, and its most ‘developed’ localities, have been building up to a perfect storm for years now—a deadly combination of fragile mountains, increasing episodes of extreme weather conditions, and haphazard construction. This isn’t unique here. Much of new India is a hotchpotch of unruly, unregulated frenetic construction, middle-class avarice and shortcuts, and a wasteland of broken laws. In Himachal Pradesh, it just amounts to a human tragedy.

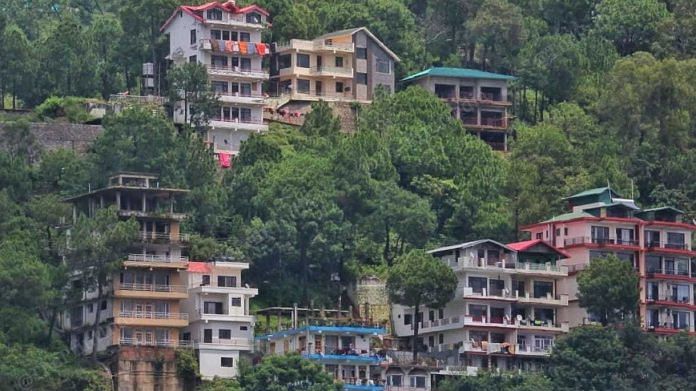

New Shimla’s residents are mostly former civil servants, while the lush oasis of Summer Hill, full of deodar trees punctuated by homes, is where former university professors live out their retirement. Originally paddy fields, an ecosystem was replaced to buttress the city’s growing needs. However, residents can’t be solely blamed for the city’s urban nightmare. Everything here appears fragile and on the cusp of collapse—poorly constructed buildings located on precarious mountain-tops and roads in a perpetual state of widening.

Elsewhere, middle-class aspiration is the cause for haphazardly conjured cities, such as Delhi and Mumbai: homes and cars are a convenient avenue for ostentation. In Shimla, according to former additional chief secretary Deepak Sanan, it’s the lack of proper incentive structures. Institutional buildings don’t follow seismic standards, and aren’t insulated against the growing number of natural disasters and increased level of precipitation. The freewheeling construction has made homeowners reckless too, emboldening them to construct rashly—multi-storey dwellings on shaky mountainsides built on steep inclines.

Elsewhere, middle-class aspiration is the cause for haphazardly conjured cities, such as Delhi and Mumbai: homes and cars are a convenient avenue for ostentation. In Shimla, according to former additional chief secretary Deepak Sanan, it’s the lack of proper incentive structures. Institutional buildings don’t follow seismic standards, and aren’t insulated against the growing number of natural disasters and increased level of precipitation. The freewheeling construction has made homeowners reckless too, emboldening them to construct rashly—multi-storey dwellings on shaky mountainsides built on steep inclines.

But homeowners take the cue from what they see around them. They are not pioneering risky constructions; they are merely aping others.

“You have to look at what becomes accepted practice. You have to look at what’s being done by opinion makers and those in positions of power. Starting from a high court that is 11 storeys and has forcibly ensured another building built in the drainage system of the nullah (drainage) next to it—for housing lawyers’ chambers,” said Sanan. “If the courts are doing this, if the government is building in fragile zones, why would individuals think otherwise?”

The lawyers’ chambers are housed in a six-storey building constructed on top of a ravine. The hill below is bulging under its weight and that of its stilted parking. Located in the heart of the city, it shares space with an adjacent government hotel.

“It’s a classic case of charity beginning at home,” Sanan said. In Shimla, there’s no hesitation about building vertically. People are content to live in precariously located homes, finding safety in numbers.

Residents here are also increasingly defensive with sensational media headlines forewarning the city’s death by climate change and its newfound inaccessibility following the collapse of Baddi bridge and the blocking of Kullu-Mandi highway. They say the reality isn’t as dramatic and that the expectations from Shimla are very different from any other crowded Indian city. “People have been saying for years that Mumbai is sinking,” says Vivek Sood, a hotelier.

Privately, though, they acknowledge the problem among themselves.

Also read: Disasters put focus on cities’ ‘carrying capacity’. It’s a textbook concept, planners don’t use it

Too glaring to ignore

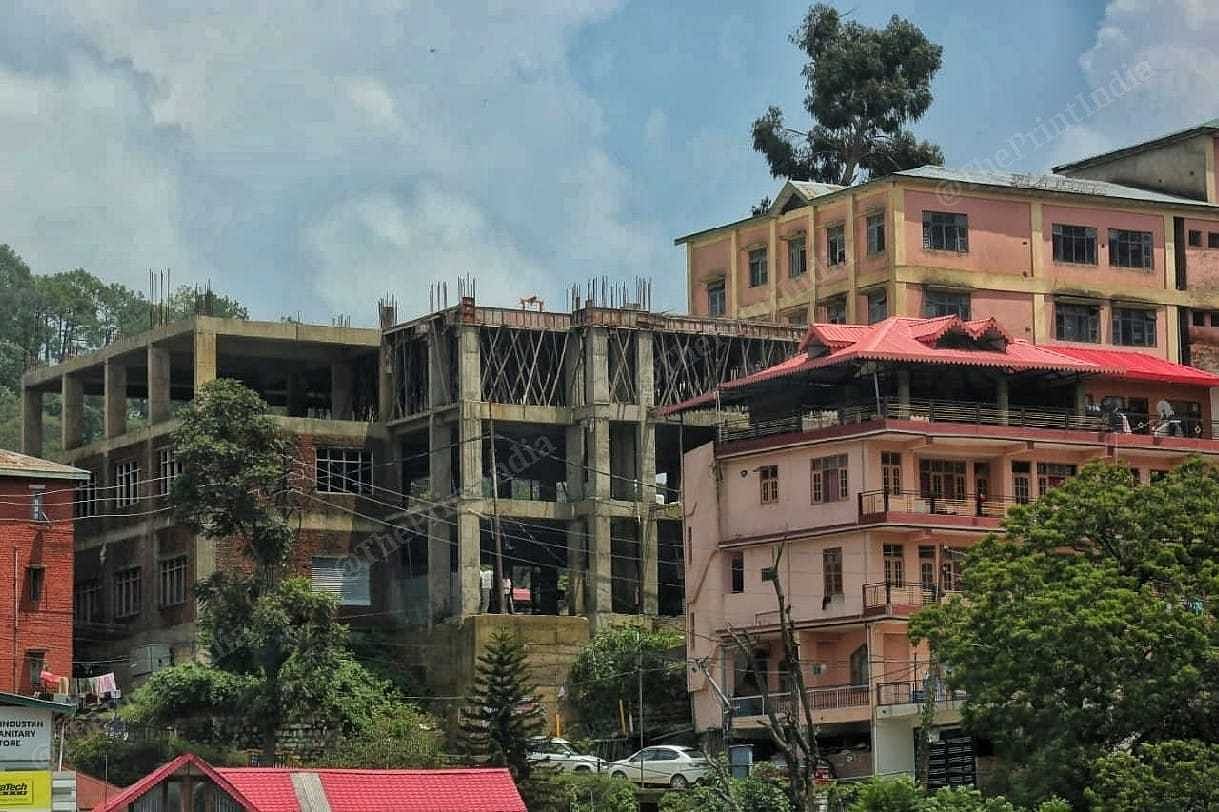

A new building under construction in the heart of Summer Hill has suddenly become a thorn in people’s eyes now.

Three days after the collapse of the Shiv Mandir that killed 20 people, Naresh Mehta, a contractor in Summer Hill, claims he is being harassed—both by the media and his fellow residents—for the ostensibly dangerous home he is building. Mehta is constructing a three-storey house at a 70-degree incline. In November 2017, the National Green Tribunal had recommended capping the incline of structures at 35 degrees.

The labourers lounging outside say it’s all for his family, but he may rent out parts of it. The most noticeable feature of its elevated, reinforced concrete driveway are the jagged cracks that have developed following heavy rain. Environmentalists point to the advent of reinforced concrete as a precursor to the state’s environmental degradation.

The rumour mill went into overdrive after, with residents whispering among themselves that Mehta was surreptitiously building a hotel—which was appalling given the circumstances. “Load bahut hai [the load is too much],” said one resident, referring to the size of the dwelling, which could make it prone to caving in.

A 20–minute drive away from Naresh’s home is a spectre of a larger and older problem—the Indira Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, a premier government institution, destined to propel Shimla forward, making it worthy of its Smart City tag. Located in Shimla’s historic ridge, the 10-storey building has a façade that looks like an ode to the colonial architecture that is definitive to the cityscape. Its most recent expansion was last year, when a new OPD block was introduced. The load borne by the mountainside is immense. Under IGMC, flows a drain, which could be inundated at any point, especially as the monsoon grows fiercer by the year. The Indira Gandhi Medical Complex on Mall Road is in a similar situation.

The office of the Urban Development Department nearby has also been hurriedly vacated for the same reason. Residential and commercial buildings didn’t always lack adequate drainage, nor were they built on top of existing drainage systems. The British kept the drainage system around Shima’s historic ridge. Their drains were never plastered with concrete, as is the case today, when homeowners and institutions cover the drains up as if they don’t exist.

This kind of building has a relatively short history. During British rule, the concretisation of drains wasn’t allowed, says Tikender Singh Panwar, the city’s former deputy mayor. They needed to be embanked.

Local people in Shimla and Solan say it’s divine retribution—it’s been pouring since March–end. The state’s designated monsoon season is June to September. This season, rainfall levels have been 93 per cent more than normal.

Awareness is creeping in belatedly among residents, city officials, and builders.

The geological breakup of the city needs to be taken into consideration, experts say, in order to decipher how deep into ground one should build, as well as the load-bearing capacity of the mountain. In the town’s Himland, another plush neighbourhood, a high-rise building was flooded with water, and residents were forced to evacuate.

“No means no. Water bodies are not to be touched. They need to be considered sacrosanct. A development plan that doesn’t take this into account is bogus and flawed,” says Panwar, exasperatedly.

Distended gorges, swollen ravines and overburdened drains should not be sites of construction. “The more water stored, the more dangerous it is. It’s against conventional wisdom,” he adds.

During British rule, when Shimla was an idyllic summer retreat, an escape from the capital’s hostile summer, planning was more robust and requisite drainage a common phenomenon. Today, the city is paying in abundance for its lack of drainage-mapping. Natural drains blocked by both construction and construction debris and weakened soil are leading to the deluge of cracks, which have caused dozens of panic-driven residents to abandon their homes in Shimla, and thousands across the state.

Also read: Himalayan Hinduism is being reshaped in Kedarnath by climate change

Cementing an illiberal construction boom

An eerie sense of disquiet has descended over Mall Road. The absence of the swarm of tourists who capture its misty lanes, occupy its cafés and buy cliché memorabilia is conspicuous as ever. Hotels lie deserted, and business owners are concerned about their mounting losses. “It’s worse than Covid,” says Sood, the hotelier. Members of the Hotel Association own 150 hotels. There are 180 members in the Mall Road Businessmen Association. Tourism contributes to about 7.8 per cent of the state’s GDP.

“As a businessman, it’s been terrible—60 days and zero tourists. We’re not going to recover for the next three months,” he rues. The association held a press conference to express their frustration and said the situation has been blown out of proportion by the media, and that they are paying the price for it.

One of Sood’s hotels is Clarkes, located bang in the middle of Mall Road. Built in 1898, its colonial-style foundation—further embellished by its red-brick roofs and green shutters—is bait for tourists. But currently, many of its rooms are empty. Only “corporates” are coming in.

Even as buildings collapse like they’re made of cards, for some in Shimla, the precarity is yet to hit home.

“Mall Road starts on the lower-bazaar level. Four storeys down, it’s been built with RCC (Reinforced Cement Concrete). It’s withstood many earthquakes and flash floods. Why shouldn’t we build,” asks another member of the association.

Experts and environmental justice groups have argued against using RCC as liberally in the hills as it is used in the plains, because it isn’t a material known to be resistant to natural disasters. This monsoon, an overwhelming number of RCC structures have caved in, or developed cracks.

For builders, the use of RCC meant anything goes.

“The combination of money coming in, the stride of engineers, and RCC paved the way for this belief—we can turn even the rivers,” says Panwar, the former mayor. Reinforced concrete ushered in Shimla’s infra-boom, a marker for the dawn of liberalisation in the 1990s.

There is an urgency for local masons and contractors to have training that aligns with the specialised nature of the landscape, out of which buildings are being carved. But no concerted effort has been made, even though plans were allegedly laid out.

There is a simple, ordinary mechanism that is employed to make buildings earthquake–resistant, says Sanan, who has been living in Shimla for over 30 years. When a pillar is being made, steel bars are put in. These bars need to be joined and then turned inwards and tied together. If the pieces are left open, the structure is vulnerable to rupturing. “When I was building my house, the mason did not know this.”

Only 32 per cent of buildings in Himachal Pradesh are in compliance with globally accepted seismic standards, found a 2017 study titled ‘Rapid Visual Screening of Various Housing Typologies in Himachal Pradesh’, authored by IIT Hyderabad researchers. The study highlights certain follies—the unavailability of flat terrain, and 55 per cent of the buildings assessed were vulnerable to collisions.

No big construction companies have made inroads into Shimla. Construction is still, by-and-large, an individual activity—performed by small–scale contractors and masons.

The literal ascent of Shimla-ites and their unsafe cement homes can also be attributed to the sheer lack of space. “10 per cent of land is under private ownership, 10 per cent with the revenue department. 70 per cent falls under the forest department. There isn’t enough space, which is also why people build vertically,” says Manshi Asher, co-founder of Himdhara Collective, a Himachal-based environment research and action collective, focused on the Himalayas. As a general trend, people do not own vast swathes of land on which they build palatial homes. But the issue is that vernacular architecture “has been systematically destroyed,” and in steadily emerging peri-urban areas, there are no regulations at all.

Kath Kuni architecture, which uses deodar beams locked together as support bases for its stone structure, is known for being earthquake–resistant. Insulation comes from its double-edged walls. The technique was passed down by families, and now risks extinction by way of RCC.

Cement has emerged as a cheaper alternative, and obtaining wood for construction, given forest laws, is an unlikely prospect. But Asher suggests that this can be regulated, and studies can be conducted regarding how much timbre is needed by a particular community: thus regulating the process. The need is pressing, as “knowledge of the terrain is being lost.” Resources, labour, skill—everything’s being directed elsewhere.

Also read: In debris of Shiv temple razed by Himachal cloudburst, broken families, regrets & a shaken community

Chipping away at natural resources

Vision 2041, Shimla’s development plan envisaged by the Jai Ram Thakur government, is stuck at the National Green Tribunal, waiting for its permission so that construction in 17 green belts could begin. An NGT ruling declared that no new commercial establishments would be constructed in the city’s core area, and nothing above 2.5 floors in the Shimla Planning Area. In the past 20 years, no new five-star hotel chains have ventured into Shimla, says Moninder Singh Thakur, chair of the Hotel Association.

A number of cases fighting for the state’s environmental viability and basic livability are pending in the courts. “People have a lot of faith in the courts,” says Asher. Panwar has filed a police complaint against the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) for criminal negligence. The ‘No Means No’ campaign in Kinnaur, a movement to save the Kinnaur Valley from exploitation and heedless development, is gaining traction.

There is growing awareness about the vulnerability of the Himalayas, and the establishment and civil society are taking note. CM Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu announced no new highway would be built without requisite drainage. Tangible, result-yielding action may be some time away, but environmental groups are wading into chaos –– which, activists say, began with the dawn of liberalisation.

As economic reforms set in, hill states were pushed to utilise their resources. This meant a potent mix of urban aspiration and negligence of the ecosystem: in this case, they’re geological formations and river-systems.

Liberalisation arrived as a precipice—and soon Himachal Pradesh needed to employ its arsenal of “natural resources” for sustenance—the push for infrastructure was immense, and tourism became bread and butter for many. Aspiration and negligence are, of course, not unique to Himachal Pradesh. “But everything is more visible in the mountains,” says Sanan.

Problems of heady construction and a quest for development with urban planning as collateral exist in most major Indian cities. But the mountains, with their slew of terrain-related challenges and unabated construction see dramatic and often dangerous results. “Every hill town in India presents problems of no parking, clogged houses stacked on top of the other, along the hillside waiting to descend—basically end up in the valley,” he adds.

Himachal is no differently placed, even though Shimla’s purportedly biggest builder, Bittoo Sharma, has only made 100 homes over the past 20 years—not a large sum. “There are aspirations,” says Asher. “But people are realising those are not going to be met through more infrastructure.” There’s aspiration in designated urban areas, but there is also disillusionment and alienation. In Kullu, the youth has majorly turned to drugs.

Rita, who lost seven members of her family in a cloudburst in Mamligh, 27 km from Shimla, says the mountains have a “defect”, owing to all the construction. Although, the supposedly new road was of no use as it got covered with broken trees and couldn’t be accessed by villagers to rescue her family.

The mountainside still looks pristine. The road gives way to a canopy of trees, made luxuriant by the monsoon. The valley looks verdant and there is a gentle trickle of rain. There is no construction debris, no family members mourning their loved ones. “It’s clean. The weather is good. So many people come from outside, they even want to get married to Himachalis,” whispers Kaushalya, a panchayat member from Mamligh.

But a new reality has taken over.

“People think Shimla is unsafe now,” says Oberoi.

(Edited by Prashant)