Sirsa: At the funeral of 55-year-old Kaushalya Devi, Ramji Jaimal nudged grieving family members out of the way to get a better angle for his videos of her smouldering body. But this small pyre was only ceremonial. Her real cremation was about to unfold elsewhere.

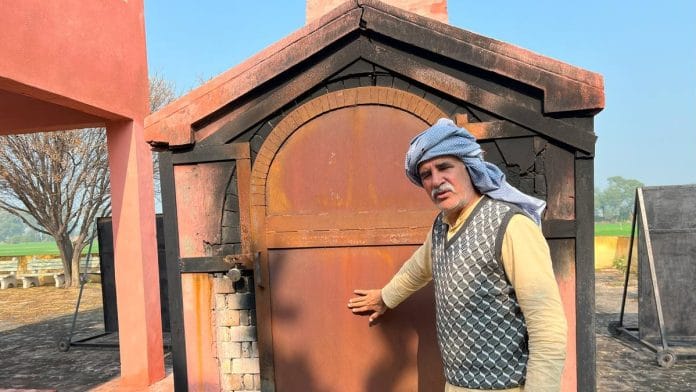

As the men of Malewala village in Haryana’s Sirsa lifted her body onto a charred platform and coated it in ghee—rituals performed with appropriate solemnity—Jaimal watched with a serene, self-contained smile. Then came the moment he’d been waiting for. Kaushalya Devi’s body was moved into a chamber resembling a human-sized oven, packed with firebricks. Inside, the temperature rose to 760 degrees, her body fat feeding the flames.

The deed was done. And Jaimal took quiet credit for it. He’s the eco-cremation crusader of Haryana.

“I have motivated everyone. I’ve gone door to door, telling them about the pollution caused by burning wood at funerals,” said the Ayurvedic doctor and grassroots environmentalist, who’s also the subject of a documentary, Before I Die, by Egis, a Paris-based consultancy firm. “This is my way of life.”

The embers of change are burning for cremation in Haryana and Punjab. Last rites are going green. Rising wood costs, pollution anxiety, a contraption that looks like an electric crematorium, and the determination of one man are driving a revolution.

Traditional cremations consume 500 to 600 kilograms of wood per body, according to a report by the Forest Research Institute (FRI) in Dehradun earlier this month. By comparison, Jaimal’s new-fangled village crematoriums, built by panchayats and local authorities, use 60 kilograms—10 times less.

This change is part of a wider trend toward making death more eco-friendly. Delhi now has 21 operational CNG and electric crematoriums and 9 per cent of funerals are green—double what it was before the pandemic. Even in Varanasi’s Manikarnika Ghat, a bastion of tradition, 18 eco-friendly pyres are planned. Rural Punjab and Haryana, however, are many steps ahead. Over 300 such crematoriums have come up in these two states over a decade or so, according to Haryana’s former additional chief secretary Sunil Gulati, who works with Jaimal through his NGO Aapsi. In Sirsa, Jaimal’s home district, nearly every village has one.

Kaushalya Devi’s family are Bawariyas, a semi-nomadic tribe from Rajasthan that migrated to Haryana. Categorised as a Scheduled Tribe (ST), they are among the many communities now using Jaimal’s crematoriums. For him, their participation is proof of its success. It shows that the concept has expanded well beyond Punjabi-speaking Jats, who were the first to adopt these crematoriums 12 years ago.

“Wood is expensive now. And so, everyone is cremating their bodies like this,” said Gurudev Singh, Kaushalya Devi’s son in-law.

We look at everything from the perspective of science. Pray when you’re alive. Not when you’re dead.

-Iqbal Singh, volunteer working with Ramji Jaimal

Outside its forests, Haryana has 4.1 crore trees. And a population of 3.1 crore people. A single cremation requires roughly two trees, amounting to about 1.5 trees per person.

“If this continues, what will remain?” asked Gulati.

In Haryana’s villages, only wealthy landowners can afford the massive amounts of firewood needed to reduce a human body to ashes. Others are either forced to buy wood or rely on the goodwill of their neighbours. For Kaushalya Devi’s green funeral, her family bought a quintal of wood—far less than what a traditional cremation would require.

In Malewala, residents showed up in droves to mourn Kaushalya Devi’s death. Men conducted the ceremonies with stoic, testosterone-filled silence, while the wails of the women—barred from entering crematoriums—filtered through. Most of the women outside had only a vague understanding of the new crematorium technology—even if it’s how their own funerals will one day be performed.

The eureka moment for Jaimal came when he visited an acquaintance’s factory in Faridabad and saw iron melting in firebrick furnaces. Bodies, he figured, could also be burnt this way.

Also Read: More Indians are seeking moksha through science. Medical colleges have surplus corpses now

‘Rationalism’ and resistance

As Jaimal’s white Isuzu meanders through Sirsa, including his home village of Darbi—lined with massive haveli-style homes— he has to stop multiple times to greet well-wishers. He’s a bit of a local celebrity, having single-handedly saved many families from exorbitant funeral costs and helped them conserve their wood, a vital resource.

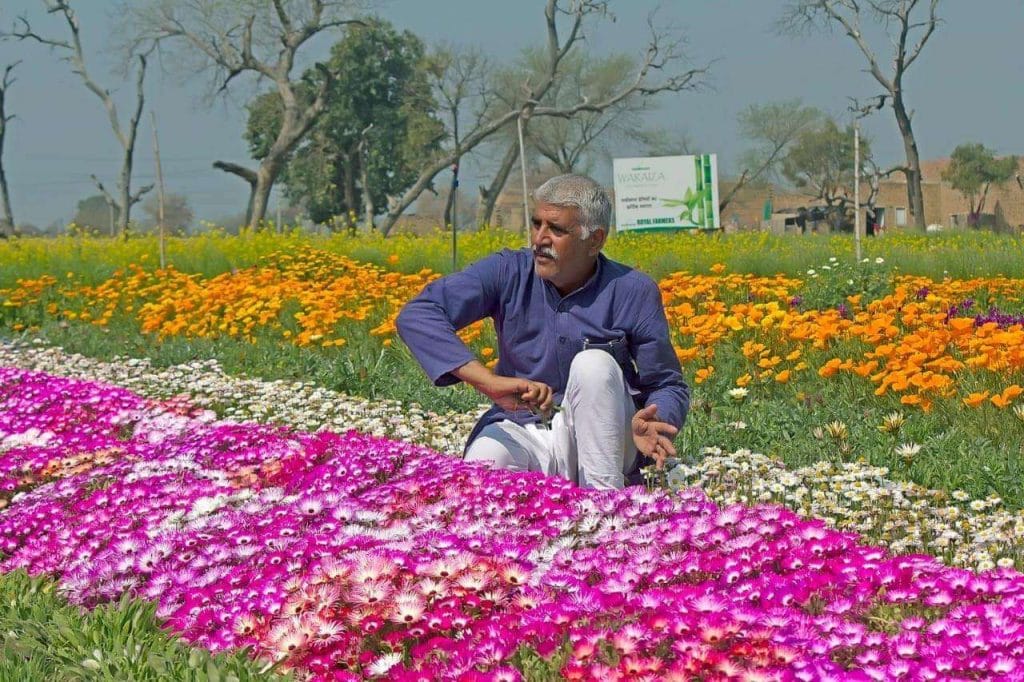

A farmer and social activist, who is known locally as the ‘flower man’ for his nationwide planting efforts, he has developed a small network of proteges over the years.

One of them is Iqbal Singh from Nezadela Kalan, who has taken up the green crematorium mantle in a big way. Death no longer fazes him, and he speaks matter-of-factly about tasks that might otherwise invite social stigma.

“I clean the crematorium every alternate day to make sure there are no bones remaining,” he said nonchalantly. “I’ve told outsiders to come as well. They just need to bring the body, and I’ll do the rest. This is our system of bhaichaara (brotherhood).”

In his pocket, Singh carries a knife to rip open packets of ghee used in funeral rites. According to him, 40 per cent of his village has already switched to the green crematorium. The option of an open cremation remains, but more families are coming around as they see the benefits. The crematorium shares a low boundary wall with fields of wheat, currently a verdant green following the harvest season. In the dry, hot months, however, the pale brown crop only needs a single spark to engulf entire villages.

Whenever an open-ground cremation takes place, the panchayat insists on having a fire brigade present. On occasion, said sarpanch Hoshiyar Singh, they’ve had to turn families away—telling them to cremate their loved ones in the city instead. Consecutive or simultaneous open cremations are simply too risky.

“We look at everything from the perspective of science,” said Iqbal Singh. “Pray when you’re alive. Not when you’re dead.”

Jaimal attributes this rationalist mindset to what he sees as an intrinsic part of Punjabi culture: a healthy scepticism of governments and a propensity to take matters into one’s own hands.

“We think at scale, and we’re a scientific people known for our internationalism,” said Jaimal, who earned his degree in Ayurvedic medicine from a college in Rohtak. “We have a clear sense of right and wrong.”

(Jaimal) is morally committed, his sense of action is strong. I would be blind if I ignored such a perso. In Sirsa, people recognised that there was a shortage of trees. It’s a reality they live with every day.

-Sunil Gulati, former Haryana ACS

But not everyone is eager to embrace the unconventional. Nezadela Kalan is also home to members of the Prajapati caste, whose funerary rituals include leaving ashes out in the crematorium. Clay pots once used to hold the ashes of their dead are strewn throughout the crematorium grounds.

In the green crematorium, the body takes only 45 minutes to burn, and the ashes must be collected the same day. Thus, the Prajapatis here are reluctant to make the switch.

“We’ve been performing cremations like this for so many years. It’s difficult to change,” said Madan, a member of the community and a resident of Nezadela Kalan. “But I’m going to tell everyone why we must [change]. Who knows, maybe with the next generation, things will change.”

Jaimal insists that environmental activism comes naturally to him since he belongs to a farming family. “A man that’s attached to his land is, by default, dedicated to the environment,” he said. “It’s hereditary.”

Flowers to funerals

Jaimal’s stature as an influencer in Sirsa was built not on social media but the old-fashioned way. Through decades of work on its soil and its ashes.

One room in his single-storey home is dedicated solely to his accolades. There’s hardly any furniture—except for a wall-to-wall shelf dripping with various awards and certificates.

His Instagram bio offers a glimpse into his achievements too: Baba Maheshwar Nath Award, Ch Ranbeer Singh Award, State Youth Award. And since there are too many to list, he ends the bio with a humble flourish: #Many other awards.

His current pride and joy is an award from the Assam Rifles—conferred in 2022 for being a ‘good citizen’. He runs a nursery on land managed by the Assam Rifles and Dogra Regiment, where he grows flowers distributed to the army.

Jaimal insists that environmental activism comes naturally to him since he belongs to a farming family.

“A man that’s attached to his land is, by default, dedicated to the environment,” he said. “It’s hereditary.”

But even if it’s in his blood, rising pollution is what gave him direction two decades ago. He’d been looking for a way to cut down on the staggering amount of wood used in cremations. The eureka moment came when he visited an acquaintance’s factory in Faridabad and saw iron melting in firebrick furnaces. Bodies, he figured, could also be burnt this way.

“I realised that this is how you could save on wood,” he said.

From there, Jaimal—who calls himself a “big thinker”—started researching. He even went to the kitchens of Ashoka Hotel in Delhi, where he studied their tandoors and ovens. These, he recalled, became the blueprint for his human-sized cremation chambers.

At first, villagers in Darbi were hesitant. But Jaimal went door to door, explaining how his crematoriums would cut costs and reduce pollution. Once a few families agreed, the idea caught on. Two years later, the villagers pooled funds to build the first two crematoriums.

The first person cremated in one of Jaimal’s chambers, over a decade ago, was a well-respected former sarpanch and a friend of his grandfather’s. His decision emboldened other villagers to follow suit.

To further his causes, Jaimal has worked with Aapsi, an NGO run by Haryana’s former additional chief secretary Sunil Gulati, for the past 18 years. It helps him with funds as well as navigating systemic hurdles.

“(Jaimal) is morally committed, his sense of action is strong. I would be blind if I ignored such a person,” said Gulati. “In Sirsa, people recognised that there was a shortage of trees. It’s a reality they live with every day.”

Another reality they face, according to Gulati, is administrative indifference.

“The administration hardly cares,” he said. “It’s as if they’re never going to die.”

Every year, 50-60 million trees are burned in cremations across the country, releasing approximately eight million tonnes of greenhouse gases.

Cow dung dreams

Jaimal wants to make cremations even greener. His biggest hurdle isn’t red tape, panchayat interference, or government inertia—it’s time.

“I’m touching 60 years now. And I’m only one man. How much can I do?” he told ThePrint mournfully.

But the winds of change are already sweeping through Sirsa.

Earlier this month, a team from the Forest Research Institute in Dehradun visited three villages in Sirsa to inspect how the green crematoriums were faring.

“This type of cremation will reduce air pollution, high ash and methane emissions from the wood, as well as excess smoke and deforestation,” declared their report.

Traditional cremations are a significant source of pollution. A 2016 IIT-Kanpur report concluded that 4 per cent of Delhi’s carbon monoxide emissions come from open-air cremations. With India recording an estimated 110 lakh deaths annually—including 1.28 lakh in Delhi alone in 2022—the cumulative environmental impact cannot be ignored. Every year, 50-60 million trees are burned in cremations across the country, releasing approximately eight million tonnes of greenhouse gases.

Even Sirsa’s green crematoriums, however, aren’t without flaws. As Kaushalya Devi’s body was reduced to ashes, plumes of smoke escaped through the closed doors, triggering coughing fits among those outside.

Jaimal blamed the weather. It was a cold day with moisture-laden air, which needed extra wood to keep the fire burning. Ordinarily, he claimed, there isn’t this kind of smoke.

His next plan is to eliminate wood entirely by replacing it with cow-dung sticks. Through funds he says he has received from an American company—he claims he’s unsure of its name—he has procured two machines and installed them on his 48-acre ancestral land. These machines process cow dung to extract waste, leaving behind fibre that can be shaped into sticks.

These cow-dung sticks, once dried, emit a blue flame—similar to CNG, according to FRI Dehradun. For now, Jaimal has been experimenting with dung from his family’s buffaloes, but plans to scale up with supplies from local gaushalas soon.

Jaimal is waiting for the next death in his village to demonstrate the technology.

“I’m certain it’s going to happen in the next few days,” he said. “People believe in me. They’ll embrace it.”

Also Read: MCD’s 1st pet crematorium giving dignified send offs to animals—memory garden, priest services

A mother’s last wish

Jaimal’s ambitions go beyond human cremations. He envisions building animal crematoriums to address the problem of carcasses left to decay on roads. He also values beauty. Whipping out his phone, he showed off before-and-after photos of a road near a local school, which now boasts colourful flower beds.

His achievements, however, haven’t come without sacrifices, and in Jaimal’s case, many fell on his wife.

“She thought she married a doctor, but she married a social worker,” he declared dramatically. “All day she slaves away in the fields. Her hands have grown rough. When she visits her family, they’re shocked to see her.”

But Jaimal says there’s no room for compromise—not when Haryana’s fate rests on his shoulders. He attributes the trust in his crematoriums to his universal popularity. He claimed he won the zilla parishad election in 2016 without spending a rupee on campaigning.

“I’m extremely loved. I’m my mother’s favourite child, my nephew’s favourite uncle, and my brother’s favourite sibling,” he said modestly.

Back at his home, the rectangular back of a window AC juts out into the courtyard. According to Jaimal, it’s his only indulgence. His 95-year-old mother sits beside him in the living room, looking at him fondly. Like her son, she is weighed down by mortality—but her wishes are simpler.

“He spends too much time servicing society. He should do more for his household,” she said.

But a mother’s love is unconditional, endlessly forgiving. And her favourite son has factored her into his mission.

“She’s already given me permission,” Jaimal said with pride. “She will be cremated in a green crematorium.”

With inputs from Sushil Manav.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)