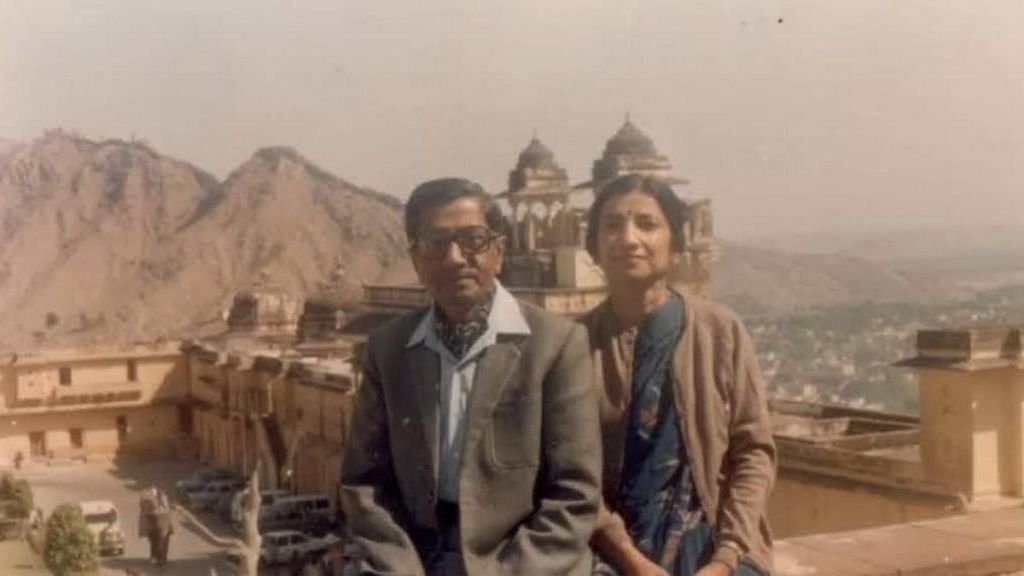

New Delhi: When Shibani Mitra was diagnosed with terminal cancer, she had two wishes: one was to be remembered as she was in her happy and healthy days. The other was to perform one last service: donate her body to science. But back then, in the year 2000, even doctors were “full of phobias” about the request, said her son Priyadarshi Mitra.

“The doctors were reluctant, or they’d act like they didn’t know what we were talking about,” Mitra said, attributing this to a general discomfort around death.

Finally, Lady Hardinge Medical College in Delhi’s Connaught Place was decided as his mother’s final destination. When she died, there was no fanfare, no elaborate rituals, and her body was quietly handed to the hospital.

Shibani Mitra was a rarity back then, but now more and more Indians are letting go of their religious inhibitions and embracing a more scientific and rationalist outlook toward death and rebirth traditions. Deh daan is now their last wish, not moksha on sacred pyres. In a country where persuading people to donate even their eyes and organs remains a struggle, these donors are bequeathing their entire bodies to medical colleges as canvases for young doctors to master their life-saving craft.

Indian medical college students used to be starved of human cadavers not too long ago, but today, some even report a surplus.

All of our bodies were unclaimed earlier. Now all are through donations. We know the medical history, and we know the family.

– Dr Sabita Mishra, Maulana Azad Medical College

Although state-specific data on body donations is lacking, medical professionals point to Gujarat and Maharashtra as the frontrunners.

“Fifteen years ago, there were very few bodies. Now the rise is due to public awareness. People feel like they are contributing to society by donating,” said Dr Sabita Mishra, head of the anatomy department at the Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC).

Between 2008 and 2019, MAMC received one or two body donations every year, but in 2022, they accepted 14. The tally so far this year is eight. Before 2014, Lady Hardinge only received between one or bodies per year, but in 2019, they welcomed 11.

Given its prestigious status, the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi is the institution of choice for the greatest number of donors in the city. Doctors at AIIMS report that they receive 30-35 cadavers annually.

“In the lower socio-economic strata, people still aren’t donating. But among people who belong to a higher socio-economic strata, we’ve seen a definitive increase,” said Dr Rima Dada, spokesperson and professor, anatomy department, AIIMS Delhi.

Doctors attribute the general uptick in body donations to awareness campaigns, body donation camps, and the work of dedicated NGOs. Some hospitals even host small ceremonies to honour donors and their families.

A single cadaver remains in service to the medical community for about 11 months. During this time, it is dissected completely — down to the bone. When a cadaver has finally given its all, whatever little remains is consigned to ashes.

India grapples with one of the world’s lowest organ donation rates, standing at approximately 0.8 per million — far behind countries like the US (26) and Croatia (36.5).

Also Read: 100s of unidentified bodies found in Delhi every year. Each a tragedy, many forever nameless

From ‘unclaimed bodies’ to donations

There are 67 storage tanks for bodies at AIIMS, and not a single one is vacant. There are 50 surplus bodies, kept as reserves.

“We’ve never had a shortage,” said Dr Dada.

AIIMS doesn’t just receive bodies — it is also the only medical institute in Delhi that transfers them to other colleges and medical facilities. “We’re constantly getting calls and requests for transfers,” Dada said.

Demand is high. Cadavers are integral to the functioning of medical colleges and hospitals. They are taken apart in anatomy lessons, subjects of medical research, and practice grounds for complex surgeries. They’re where future doctors are made.

“Cadavers are very helpful for our research. They help in anatomy teaching, in micro-anatomy teaching. When doctors and post-graduate students practice on these bodies, they get a very life-like picture,” said Dada.

Medical colleges drill into students early that the cadaver is the “first and silent teacher”. But there is such a thing as too silent. Earlier, it was a huge struggle to procure cadavers, so medical colleges had to rely on unclaimed corpses. There was no medical history for these unclaimed bodies, and no idea of potential infection risks.

“All of our bodies were unclaimed earlier. Now all are through donations. We know the medical history, and we know the family,” said Dr Mishra. “I won’t say it’s good, but it’s adequate.”

Working with unclaimed bodies also meant that doctors had to navigate bureaucratic hurdles, at times confronting uncooperative police. In cases labelled as medico-legal, the body remained in police custody, confined to a mortuary for three weeks.

“We’d lose a lot of time,” said Dr Sheetal Joshi, a professor in the anatomy department of Lady Hardinge.

In the West, sophisticated synthetic cadavers or “syndavers” are becoming more popular, poised even to replace the real thing. But in Delhi, doctors are dismissive of human replicas. “They aren’t useful. There’s the body, the system, the bones. They don’t have all the features,” Joshi said.

The process for body donation is straightforward, requiring only a death certificate by a registered medical practitioner and a form filled out by a close relative.

A new tradition

At MAMC, doctors, nurses, and even parents of students have pledged their bodies.

Similarly, when one family member takes the plunge, it often sparks a chain reaction. After Shibani Mitra donated her body, her husband, Brig (Dr) Niranjan Mitra, followed suit in 2016, also requesting “no ceremonies”.

“After seeing my parents, my mother-in-law also decided to donate her body,” said Priyadarshi Mitra. Both he and his wife have pledged their bodies too.

To the Mitras, it was a decision that came easily. Priyadarshi’s father was an army doctor and the family learned to take a clinical perspective on matters of life and death.

But they deviated from other norms as well.

“My parents were sort of unorthodox,” Mitra said. “My mother told us not to put any pictures of her in the house. No guest entering our home should see any photographs of her. A family picture was fine. But nothing of her alone.”

However, despite their readiness and belief that they were doing something noble, the process of body donation was not easy.

“Think about it. Would you donate your body?” is a question asked by multiple doctors, in reference to the sense of unease that edges death.

First, they had to navigate the harsh terrain of grief and then confront logistical challenges.

“The college did have some kind of a transport arrangement, but I live in Faridabad, so I had to call another ambulance,” Mitra said. Then, his mother’s eyes had to be transported to a centre in Noida, where they would eventually benefit two recipients.

Sixteen years later, when Mitra’s father passed away, the process of body donation to Lady Hardinge proceeded more smoothly.

Giving after death

Due to an interplay of spiritual beliefs, awareness gaps, and logistical hurdles, India grapples with one of the world’s lowest organ donation rates, standing at approximately 0.8 per million — far behind countries like the US (26) and Croatia (36.5).

There is no comprehensive nationwide data for body donation, but one thing is clear: it remains a deeply uncomfortable subject, often clashing with religious sensitivities and causing squeamishness.

“Think about it. Would you donate your body?” is a question asked by multiple doctors, in reference to the sense of unease that edges death.

“Of course, it’s a good principle to pledge your body to medical research. But there are cultural and religious beliefs. People believe in either burying or cremating,” said Dr Joseph Amalorpavanathan, vascular surgeon and founder of the Tamil Nadu organ transplant board.

In Maharashtra and Gujarat, there’s more respect given to the cadaver.

-Dr Sheetal Joshi, Lady Hardinge Medical College

But the body donation landscape is evolving. To tackle religious reservations, some body donation NGOs delve into scriptures and mythology. For instance, an article in the e-journal of the Dadhichi Deh Dan Samiti quotes a Bhagavad Gita verse that speaks of the immortality of the soul and compares the body to shed clothing.

Even some religious organisations are doing their bit, including the controversial Dera Sacha Sauda, led by rape and murder convict Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh. The dera carries out body donation awareness and registration drives. A senior doctor, speaking on condition of anonymity, praised their operations as “well-managed” and “attracting a large group of people”.

Practical questions are also being addressed. The Parashar Foundation’s initiative, Organ Receiving & Giving Awareness Network (ORGAN) India, for example, hosts an online directory with information about medical colleges and body donation centres across India where individuals can register to donate their bodies after death.

When the time comes, the process for body donation is straightforward, requiring only a death certificate by a registered medical practitioner and a form filled out by a close relative. In the case of medico-legal situations, obtaining a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the police is necessary.

Local NGOs often serve as intermediaries between the medical institution and the family, in addition to their grassroots efforts to raise awareness.

Western advantage?

Advocacy efforts for body donation have been particularly successful in Gujarat and Maharashtra, according to doctors.

The Bombay Anatomy Act 1949, which applied to undivided Gujarat and Maharashtra, was the first of its kind, opening doors to normalising cadaveric donations. The law was created to regulate the provision of unclaimed bodies to hospitals and educational institutions, explicitly for “the purpose of anatomical examination and dissection, as well as other related educational objectives”.

Today, the amended law, for both Gujarat and Maharashtra, includes provisions for body donation, a distinction shared by only ten states in the country.

“In Maharashtra and Gujarat, there’s more respect given to the cadaver,” said Joshi. The first cadaveric donation in India, notably, was from Maharashtra.

Grant Medical College, attached to JJ Group of Hospitals in Mumbai, has always had enough cadavers, according to Dr Pradnya Gurude, a professor at the anatomy department until June, when she shifted to Kohlapur. While she was not at liberty to divulge exact numbers, Gurude said that the college had a “surplus”.

However, a new challenge has emerged. The number of students admitted to the college has increased from 200 to 250 since 2019, but there is not enough space for additional dissection tables.

“There’s no space for 25 tables,” Gurude said. If there was, the college would be able to meet the recommendation of one body for every 10 students.”

Handling a person’s dead body who was once alive has made one rethink about the sacrifice he made by donating his body.

-A medical student

In Gujarat, Dr Shailesh Patel, professor and head of the anatomy department at the Government Medical College (GMC), Bhavnagar, attributed the improved numbers of body donations to the diligent efforts of organisations like the Red Cross, which also facilitate the connection of donors with medical colleges.

“Red Cross is very active here. They motivate people. They get their own ambulances. When people contact us, we tell them to call Red Cross,” Dr Patel said. “There’s enough public knowledge. We have a sufficient number of bodies.”

GMC Bhavnagar, he added, typically receives 30 bodies each year and occasionally even transfers some to other medical colleges.

The institution is well-equipped, with a four-body capacity mortuary, an embalming room, and two tanks. However, this year, it has not accepted body donations as the anatomy department had to relocate temporarily to a less spacious area due to monsoon-related damage.

Also Read: Dying with dignity is now easier. Experts say next step is to educate people on their rights

A day at work

In a large and airy room at MAMC, a dozen bodies lie on gleaming stainless-steel tables. They are all covered from head to toe with faded white sheets, bar the occasional crop of grey hair, or a pale hand.

The dissection hall expands into a dingier cleaning area, where the storage tanks are kept. The embalmed and preserved bodies need to be lifted out of the tanks and onto the dissection tables. It’s arduous physical labour, and not everyone is willing to do it.

“We have a staff crunch,” Dr Mishra said. “Some of our people have worked here for years, so they’re fine with it. But it’s difficult to get people to do the actual physical labour.”

The bodies are preserved in formalin tanks, but we keep the organs to make specimens.

– Dr Rajendra Marko, Indore Government Medical College

Overall, doctors at AIIMS and MAMC express satisfaction with their facilities, including the size of their dissection halls and tank capacities. “We have cement tanks and deep freezers,” said Dr Dada of AIIMS.

This is not the case at all Delhi hospitals, and the carrying capacity of AIIMS surpasses the rest.

At Lady Hardinge, for instance, the absence of a mortuary adds to the already challenging practicalities of transportation and storage, but work must continue.

In the dissection room, a postgraduate medical student painstakingly empties out the insides of a blackened body.

A mangled leg, rendered a listless grey by formaldehyde, rests on a table nearby. On a tray beside it, are gobs of yellow tissue: fat from the same leg.

Hospitals commonly use arterial embalming methods to preserve bodies. It involves draining the body of blood and other bodily fluids and injecting a strong formaldehyde-based solution to slow decomposition.

An acrid smell pervades the air, although doctors and students don’t seem to notice it.

An adjoining temperature-regulated room contains several ordinary dustbins, piled high not with trash but lungs and livers.

“The bodies are preserved in formalin tanks, but we keep the organs to make specimens,” said Dr Rajendra Marko, an anatomy professor at the Indore Government Medical College.

Some of these specimens find their way into medical college museums. Enlarged organs, foetuses, and other genetic anomalies make the cut and are displayed in neatly labelled jars.

Some even see these as a kind of legacy. “Please preserve my brain in the museum,” a nurse once requested Dr Joshi.

A big toe

With voluntary body donation gaining ground, the medical community is treating cadavers not just as specimens, but as individuals deserving of respect.

Colleges offer certificates to donor families, expressing their gratitude and acknowledging the gravity of their contribution. Lady Hardinge and MAMC hold felicitation ceremonies, bringing to life the stories of the donors before they became subjects on the dissection table.

First-year undergraduate medical students must take a module in their anatomy curriculum called ‘Cadaver as a first teacher’.

Introduced in the 2016-17 academic year, it was designed to sensitise students to body donation and bioethics.

Students are encouraged to form a connection of sorts with the cadaver as a step to help them develop the empathy necessary for compassionate patient care.

“Handling a person’s dead body who was once alive has made one rethink about the sacrifice he made by donating his body,” said one student quoted in a study about the impact of this module.

“The importance of seeing and being able to visualise the nerves, muscles, and vessels is paramount. This is where the cadaver takes on the role of our first teacher,” testified another.

Joshi has had experiences where donor families have been exhilarated by their contribution. “They make it like a festival,” she said.

But the respect and sense of purpose aren’t enough for everyone. Death is shrouded in fear, and it’s difficult for many to let go. Relatives grapple with the fact that they’ll have no ashes or tangible remains.

“Even when it’s all done, families retain that attachment,” Joshi said.

Sometimes, family members ask for a small physical memento from the body. Usually, they are given some hair. But Dr Shailesh Patel in Bhavnagar once fulfilled an unusual request. He ‘returned’ something to a family: a donor’s big toe.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)