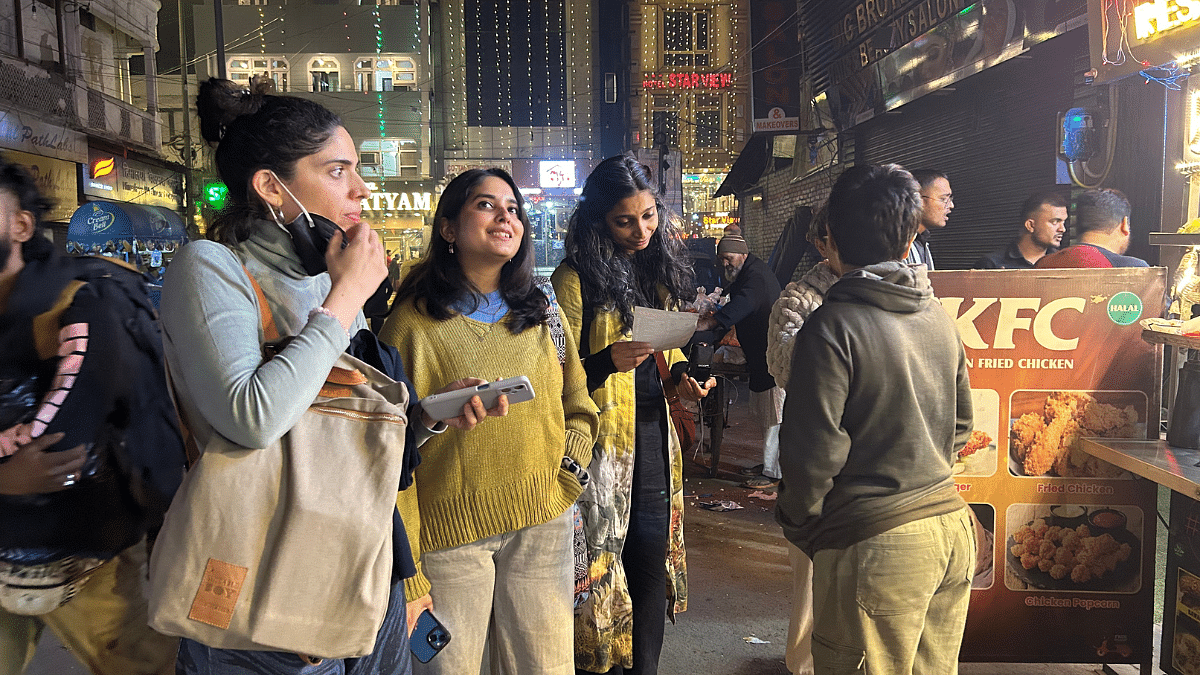

New Delhi: Geetanjali Kalta cringes as a male passerby casually approaches her and whispers into her ear, “Aaja meri jaan (Come my love).” As he saunters past her, she grimaces. It’s 10.30 pm, and men have already claimed the busy streets of Delhi’s Paharganj market. They are eating kebabs on a chilly Saturday night, some smoking and sipping on piping hot chai, but everyone stops to stare at Geetanjali. In the brightly lit streets, there are no women around — but for Geetanjali and the six women with her.

“Did you hear what he said? It has already started,” says Geetanjali, an audio engineer and performer. The leader of the group of women, Mallika Taneja, sniffs in disgust. “They are not even creative with their cat-calling,” she says.

Taneja, a playwright and actor, shocked India’s conservative theatre scene when she stripped naked on stage in Thoda Dhyan Se (Be A Little Careful) to protest against gender inequality and sexual harassment. She’s getting women to reclaim the streets of Delhi and other Indian cities at night through her platform, Women Walk at Midnight.

The initiative is part of Delhi’s long history of women-led movements to reclaim public space, from Slut Walk (renamed Besharmi Morcha in 2011) to Take Back the Night in 2013. More recently, in 2020, the National Commission for Women (NCW) organised Power Walk in Delhi to create awareness about rape and acid attacks.

Also read: ‘Largest number of uniformed persons punished by law’—But Vachathi women’s battle not over yet

‘Good girls’ in Paharganj

Delhi by day is as different at night as Dr Jekyll is from Mr Hyde. The city regularly tops the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) list for the most number of crimes against women. In 2021 (when the last report was released), there were 14,277 cases of crimes against women in Delhi, compared to Bengaluru(3,127) and Mumbai (5,543).

Tanjeja launched Women Walk at Midnight back in 2016, four years after thousands of men and women came out on the streets to protest against the gangrape of a young woman who came to be known as Nirbhaya.

“Nirbhaya changed everything for the city. Everybody was shaken to their bones,” says Taneja, recalling the days after the news broke across Delhi.

The rape was a turning point in India’s legal history — Acts were amended, punishments became harsher, and juveniles could be tried as adults if accused of “heinous crimes”.

“But really, nothing has changed,” says Kalta. The lecherous gaze, pick-up lines, hoots and whistles are still the norm. And then there’s the fear of being assaulted, attacked, or raped.

By day, Paharganj is famous for its backpackers market, brightly lit streets with colourful lights and large neon sign boards of hotels and shops selling antiques, souvenirs, tapestries, and dream catchers. At night, it’s notorious for attacks on women, petty theft, and even the occasional murder.

‘Good girls’ don’t go to Paharganj at night.

Lavanya, a 21-year-old student of political science in Delhi, had to lie to her parents to attend the walk even though she was born and raised in the neighbourhood.

“I told them I was attending a musical concert outside Paharganj,” she says, acting as the group’s guide and recommending the best shops for food. The women laugh and talk among themselves, drawing safety in their numbers.

It’s a novel experience for Lavanya. She’s a tourist in her own neighbourhood. “I have lived here all my life, but I have never strolled through the lanes of Paharganj at night. This walk means a lot to me.”

But even then Taneja, who leads the group from the front, is cautious. Stick close together, she warns as they enter a narrow bylane.

A walk to reclaim

As the women get to know each other, hesitant whispers become full-blown conversations about their experiences with Delhi men at night. The consensus is that women in Delhi don’t claim public spaces—or they’re not allowed to. The societal response to violence has been to restrict women’s outdoor mobility.

A few minutes later, the women stop to gaze at a heritage haveli sandwiched between two newly constructed hotels. There’s graffiti sprawled on the faded grey wooden door. The niches within the arches are filled with trash, but it doesn’t take away from the beauty of the structure. The women stop to take a selfie before moving on.

Soon, the walk becomes a fun stroll with selfies, snacks, and stories. They stop once more for burgers and later, buy some popcorn and nankhatai.

While some join the walk to explore the city, Taneja said she and other women like her want to normalise the presence of women in public spaces. To revel in the freedom that every man takes for granted.

Why does the city belong more to them [men] and less to us? No city is the domain of men, it is the domain of all the citizens who occupy it, says Taneja.

The motto of Women Walk at Midnight reflects this sentiment: ‘We walk when we want to, where we want to. We walk because we can!’

Since it started, Women Walk at Midnight has held around 60 night walks with women from Bengaluru, Faridabad, and Guwahati as well. “Of course, walking at midnight is not an original concept. It has been happening in many forms in many parts of world for years. But we are all building on movements that have existed globally for many years, and we try to take it forward,” says Taneja. “We gathered once, and then it kept happening again and again.”

Among their routine walks, one is the most important. It’s the one Taneja organises on 16 December every year from Munirka to Saket to bring back the conversations that started after the Nirbhaya rape case. Women Walk at Midnight expanded its presence to Cape Town in South Africa in 2022, where around 80 women joined in.

Most walks last for a couple of hours; a few have stretched through the night. There were times when people slowed down their cars, rolled down their windows, and persistently tried to convince the women to accept a lift. They have been harangued for being out late at night, and few ‘well-meaning’ uncles have asked them to go home. One of the more disturbing walks was at Hauz Khas, a popular heritage and party spot in South Delhi. “Men were acting like they owned the place,” says Taneja.

It happens at Paharganj too.

When Taneja stops in front of a haveli door, a man passing by yells: “It is midnight! Go home!”

But Taneja is unfazed and ignores him. “Isn’t this city mine as much as it is of the people who are looking at me right now?” she tells the group.

Experiencing Delhi

Anshika Sharma, 24, experienced Delhi for the first time through a midnight walk. As a Delhi University student, she used to party late with her friends and still enjoys the occasional night out as a working professional.

“Growing up, I had never strolled on roads at night. I had never seen women on streets so late at night,” says Sharma. She discovered the walk on her Instagram feed and decided to sign up.

Two other popular women-led initiatives, Ladies Night Walk and City Girls Who Walk Delhi, also focus on normalising the presence of women in public spaces, including parks and heritage sites such as Lodhi Garden, Qutub Minar, and Safdarjung Tomb.

Even before Nirbhaya, women have been trying to take back the city’s streets, gardens, and public spaces. Besharmi Morcha, which was held more than a decade ago, was part of an international movement that began in Toronto after a police officer said women should “avoid dressing like sluts” if they didn’t want to be sexually assaulted.

But more often than not, the freedom that women experience is limited to the event. Lavanya, for instance, says she will never step out alone at night. “l will be an easy target. There are high chances of emotional or physical abuse.”

Toward the end of the three-hour walk, the women stop at a paan seller known for his fire paan, a sweet mixture wrapped in betel leaves. The paan seller sets it on fire and pops it into the customer’s mouth.

A group of young men stand behind them, frustrated that the paan seller is serving the women. “You’re giving your attention to the dusra (second) gender,” says one of the men in the line.

As the women try their first fire paans, the vendor turns to the men. One of them in skinny jeans and a leather jacket—barely in his 30s—grabs it from him. “We don’t want you to feed us. We are sigma males.”

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)