New Delhi/Saharanpur: As the sun climbed higher over Akbarpur Bans village in UP’s Saharanpur, 79-year-old Kishore Kashyap and about 30 other villagers crammed themselves into two tempos. They jolted along 40 km of unpaved roads for three hours, bound for Defence Minister Rajnath Singh’s 10 April rally in Pansar. After reaching, they squeezed into a seating area packed with some 1,500 people, and began a long wait for the minister, unease soon overshadowing their excitement.

“I am getting suffocated inside, and outside the sun is too intense,” Kashyap complained, stepping outside for a breath of fresh air. He squinted against the harsh sun, wiping the sweat beading on his forehead with his gamcha.

The scenes at the rally were a grim reminder of last year’s tragedy in Navi Mumbai’s Kharghar, where 14 people died and over 600 were hospitalised with heat-related complications after attending a function organised by Maharashtra’s BJP-Shiv Sena government. With the anniversary on 16 April, it seems few lessons have been learned.

As the Lok Sabha elections approach, scheduled in phases from April 19 to June 1, political parties are on a spree of organising rallies and political gatherings. Despite last year’s fatal outcomes, the same pattern continues: large crowds, events during peak heat, inadequate attention to shade and water. But now, with the India Meteorological Department (IMD) predicting “extreme heat waves” in its forecast for April through June, any oversight could have grave repercussions.

At the Pansar rally, organised by the BJP’s Saharanpur district unit, it seemed even the country’s richest political party had taken few steps to prevent another heat-related tragedy, despite claims to the contrary.

Along with organisers, people also have to be responsible participants. While gathering for such events, always ensure that you carry ample water and an umbrella, and avoid prolonged exposure. The Election Commission of India has also issued guidelines on the management of poll rallies

-Abhiyant Tiwari

Originally scheduled for 11 am, the rally was delayed until after 12:30 pm, when the heat and humidity levels had started to peak. The venue— the middle of a field—lacked access to shade or water beyond the immediate vicinity of the rally area.

“We have made arrangements for water and for people to sit,” said Vijender Saini, one of the members organising committee. “The volunteers were working all night to ensure that people were comfortable. The party’s central leadership also approved the arrangement plan.”

However, the oppressive heat was clearly taking a toll. People swarmed around the only water station, which had small jugs dispensing increasingly warm water, offering little relief. Beyond the security checkpoints, additional water was not allowed.

“It is uncomfortable but elections are important. It comes only once in five years,” said Suneeta Rani, a member of the BJP women’s wing. She had come with her five-year-old daughter, who was tugging at her mother’s dupatta seeking refuge from the blazing sun.

But in Kharghar, it was these “minor discomforts” that, unaddressed, snowballed into death and devastation. And it was all triggered by basic oversights in event management. An investigation showed that simple, timely planning could have easily prevented the loss of lives.

Autopsies confirmed that the victims had been without water and food for at least the event’s seven-hour duration, reportedly contributing directly to their deaths. While authorities claimed to have arranged for 2,100 water taps and 74 tankers, they failed to take into account the large crowd that turned up for the event. Attendees said that the water ran out after noon, and the combination of overcrowding and high humidity worsened the impact of the heat.

The Khargar deaths also exposed a hole in the early warning system. No functioning IMD observatory near the event site meant no alerts were issued about the heat and humidity. The nearest IMD station, Santacruz, predicted a maximum temperature of 34-35°C, but it was 35 km away from the event site. Another observatory, the Thane-Belapur Industrial Association station did flash the maximum temperature to go up to 38°C, but did not warn of the high humidity levels. Later, IMD officials said that the Rabale observatory, set up in 2017 and 222 km away, did not have the historical data needed to set a baseline temperature, which is necessary for issuing heatwave warnings.

As campaign season peaks, the scale of public gatherings across states is ramping up. But with the mercury also rising, is the safety of these much sought-after crowds truly being considered?

Also Read: CEEW to iFOREST, Modi govt listens when think tanks talk. They are growing in clout & cash

A wake-up call for elections

The Kharghar debacle was chalked up to the IMD and authorities being caught off-guard. This time, however, the Met Department has already issued warnings of a brutally hot summer, leaving no room for complacency.

In its summer forecast on 31 March, the weather agency predicted that India will experience more than double the usual number of “extreme heat” days in the summer months. Around 10 to 20 heatwave days are expected across the country, compared to the typical four to eight that are usually recorded in a year. Gujarat, parts of Maharashtra and Karnataka are expected to be worst affected, followed by Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Andhra Pradesh.

Given the polls, the heat isn’t just a weather concern—it’s a political one. Kiren Rijiju, Union Minister of Earth Science, linked the forecast directly to voter safety during his press briefing on the forecast.

“We have to be extremely careful during the electoral process. People have to cast their votes while braving severe heat conditions,” Rijiju said. “All the stakeholders, including state governments, have made elaborate preparations. A large number of lives have been lost in the past due to extreme heatwaves.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi also seems to have taken a hands-on approach. On 11 April, he chaired a meeting to review preparations for the impending heatwave, especially in the context of elections. The meeting reportedly focused on spreading awareness across various platforms in regional languages and ensuring that health facilities were stocked with essential medicines, intravenous fluids, ice packs, ORS, and so on.

In March, too, the IMD had warned of “stronger and longer” heatwaves, after which the Election Commission had issued guidelines from the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) to the chief electoral officers of all states and Union territories, asking them to provide facilities like water and shade at polling stations.

The number of heat-related deaths being reported currently across the country is probably much less than the actual count

-Dr Dileep Mavalankar, director, Indian Institute of Public Health in Gandhinagar

–

But the dangers are not limited to polling days. “The point to note here is that voting is not a mass event, it is the rallies that are,” said Abhiyant Tiwari, who leads health and climate resilience at the Natural Resources Defence Council.

Public awareness is an essential aspect of heat management, according to him. “Along with organisers, people also have to be responsible participants. While gathering for such events, always ensure that you carry ample water and an umbrella, and avoid prolonged exposure. The Election Commission of India has also issued guidelines on the management of poll rallies,” said Tiwari.

Madhavan Rajeevan, former secretary, MoES, said that the economically weaker sections are the most vulnerable to heat and these are also the people who mostly form the crowds at election rallies. This, he said, was called “heat inequity”.

What happens in a heatwave?

Voting in Lok Sabha elections has almost always been a sweaty affair in India, as they typically take place in the sweltering summer months. But things are getting hotter. The previous decade, from 2010 to 2019, was India’s hottest on record, with heatwaves becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change.

The IMD uses a two-pronged approach to define heatwaves. First, they look at regional temperature increases. When temperatures in the plains exceed 40°C or 30°C in the hills, and this rise is more than 4.5°C above the normal range, a heatwave is declared. A “severe heatwave” is when the temperature departure jumps to over 6.4 °C.

The IMD also considers absolute values. If the mercury rockets to 45°C or higher, regardless of the usual highs, it’s classified as a heatwave. When the thermometer reads 47°C or more, it meets the criteria for a severe heatwave.

These cold, hard numbers translate to temperatures that can be fatal for humans with prolonged exposure.

Every year, records show hundreds of heat-related deaths, but Dr Dileep Mavalankar, director of the Indian Institute of Public Health in Gandhinagar, suggests the actual casualties are significantly underreported.

“The number of heat-related deaths being reported currently across the country is probably much less than the actual count,” said Mavalankar, who headed the expert committee that prepared India’s first heat action plan in Ahmedabad. “Most hospitals, especially in tier-two and -three towns do not even have proper equipment to categorise a patient coming in with heat-related complications.”

The impact of heat ranges from mild heat rash or ‘prickly heat’ to more severe effects like heat exhaustion, cramps, dehydration, and heatstroke, Malvalankar said. Continuous exposure to intense heat is also known to trigger heart attacks and strokes.

When such extreme weather conditions strike, a heat management plan requires action at multiple levels, according to Malvalankar. The first step is to identify the most vulnerable populations within a city or state who are most severely impacted by heat. Then, leading up to summer, local authorities should prioritise providing them with shelter, water, and other basic amenities. Additionally, it has to be ensured that people are not exposed to peak temperatures during the hottest hours of the day.

“Hospitals and primary healthcare facilities should also be stocked with supplies of basic heat care such as electrolyte, rectal thermometers etc, to ensure timely care can be provided,” he added.

But simply taking post facto action won’t be enough to manage the future threats of climate change in India.

There is widespread consensus that heat action plans help reduce mortality. They serve as step-by-step guides for agencies, clearly explaining actions that must be taken once a heatwave is declared in a certain area.

Heat action plans & implementation

The relentless heatwave that struck many parts of India in May 2010 wasn’t just a human crisis. Even bats, peacocks and livestock were dropping dead. Gujarat, where the temperature soared past 48°C in some locations, bore the brunt. Hundreds of people were showing up daily at hospitals with dehydration, food poisoning, and heat stroke, and 1,344 people died in Ahmedabad alone.

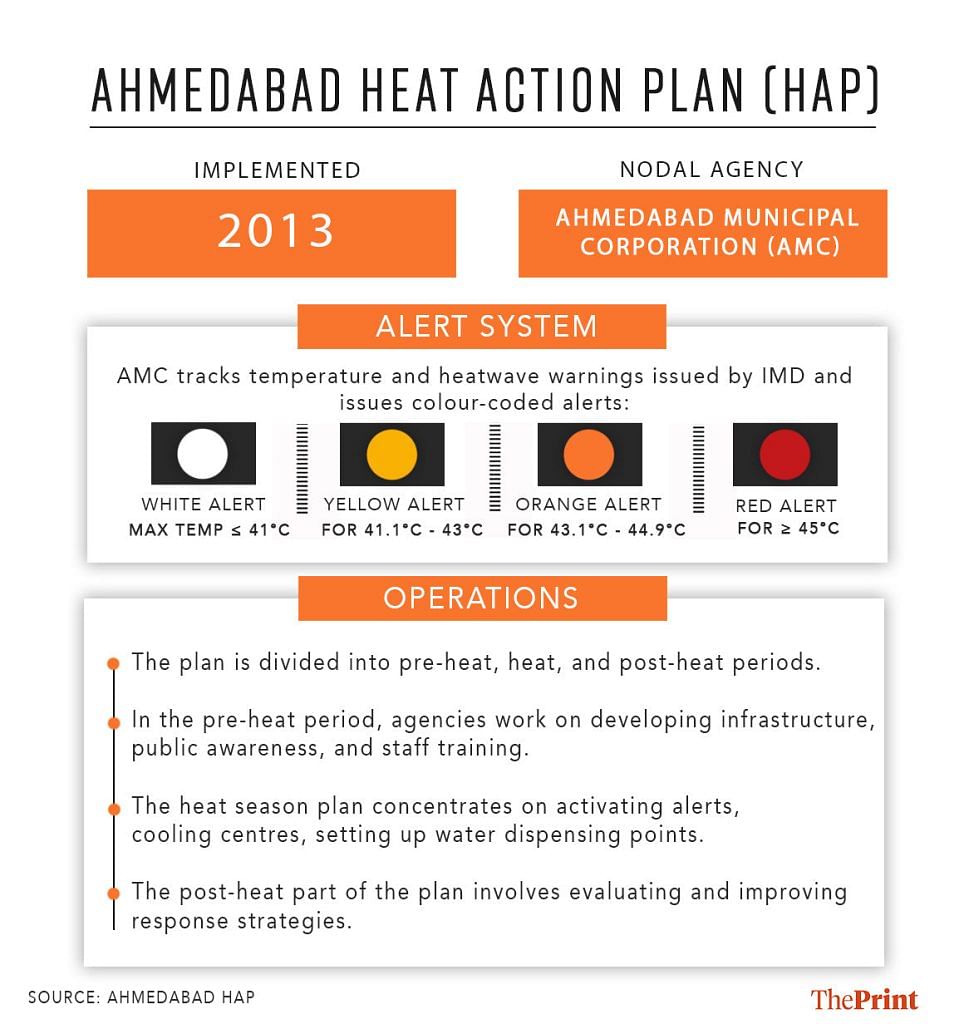

It was a wake-up call. In 2013, Ahmedabad rolled out India’s first heat action plan (HAP)—a framework for responding to extreme heat events, including warning the public and outlining steps to minimise risks.

Since then, multiple agencies have been involved in preparing early warning systems and heat action plans at various governmental levels—panchayat, district, and state. And they are getting more sophisticated.

We plan on expanding this system further and making it more efficient. We have started issuing colour-coded warnings, dos and don’ts, and also advisories for the vulnerable sections.

-M Ravichandran, secretary, Ministry of Earth Sciences

Last year, the IMD, in partnership with the NDMA, launched a new early warning system, providing heatwave alerts to the public between three to five days in advance.

Now, the plan is to expand outreach by sending messages to people through public messaging systems, mobile phone texts, and WhatsApp alerts.

“We plan on expanding this system further and making it more efficient,” said M Ravichandran, secretary of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, which oversees the IMD. “We have started issuing colour-coded warnings, dos and don’ts, and also advisories for the vulnerable sections.”

There is widespread consensus that heat action plans help reduce mortality. They serve as step-by-step guides for agencies, clearly explaining actions that must be taken once a heatwave is declared in a certain area for an efficient and quick response.

In Ahmedabad’s case, for instance, the HAP has been credited with saving thousands of lives. A 2018 study found that it prevented about 2,380 deaths, and government estimates suggest that it saves at least 1,100 lives annually.

One of the newer HAPs to be pushed into action is Jodhpur’s. Adopted in 2023, it is lauded as one of the most thorough HAPs in the country, according to heat experts who have assessed the plan. The need for such a plan in Jodhpur became especially evident after the district’s Phalodi town recorded a daytime temperature of 51°C in 2016, the highest ever documented in India.

NRDC’s Abhiyant Tiwari, who contributed to both the Jodhpur and Ahmedabad HAPs, said that there was evidence that countries that had a functional early warning system or some form of disaster management plan saw at least eight times less disaster-related fatalities than those that didn’t.

Both the Ahmedabad and Jodhpur HAPs lay out short- and long-term interventions for government agencies to follow. Short-term actions include identifying vulnerable populations, such as the homeless, elderly, and children, and providing them with safe shelters before heatwaves strike. Other key measures include adjusting labour hours to avoid peak heat, setting up water dispensing points and cooling centres, and closing schools on extremely hot days.

Long-term interventions require larger-scale government planning and infrastructure adjustments to address the long-term impacts of climate change. Examples include building heat-resistant buildings, implementing cooling roofs, developing heat warnings for farmers, and adopting climate-resilient agricultural practices.

However, there’s a question mark over the effectiveness of many heat action plans, estimated to number around 100. Last year, the think tank Centre for Policy Research analysed 37 HAPs from 18 states. Examining plans at the city (9), district (13), and state (15) levels, it found that most were underfunded, insufficiently transparent, and not built for the local context. The analysis also highlighted that most plans had an oversimplified view of the hazard, were poor at identifying and targeting vulnerable groups, and had weak legal foundations.

The report called for a change of approach, pointing out that the “science is clear” that summers are lengthening, nights and days are becoming hotter, and heatwaves are getting worse. “High resolution, downscaled climate projections are available for India and must be used in HAP revisions in addition to past temperature trends,” it recommended. “This will make HAPs anticipatory tools for heat planning rather than reactive tools of heat management alone.”

Also Read: ‘Underfunded, not built for local context’: Think tank CPR on heat action plans of 18 Indian states

Heat is no equaliser

Heat does not affect everyone equally. On the one hand are those who can escape the scorching sun in air-conditioned comfort. On the other are those who must brave the heat to make a living and then return to bake in concrete boxes or kachcha homes for the night.

And for those on the tougher side of this divide, life is only getting harsher.

An IMD report, released last April, spells it out clearly—by 2060, not only are heatwaves expected to last 12 to 18 days longer across most parts of India, but the hardest hit will be the economically disadvantaged sections.

These are the people labouring in fields, breaking stones at construction sites, or being herded to make up the numbers at political gatherings, depending on the day.

Madhavan Rajeevan, former secretary, MoES, said that the economically weaker sections are the most vulnerable to heat and these are also the people who mostly form the crowds at election rallies. This, he said, was called “heat inequity”.

“The most vulnerable to intense heat are definitely the poor people. The farmers, the labourers and daily wage workers do not have the luxury to work in air-conditioned setups. The government has now mandated that during intense heatwaves no work should be allowed between 11 am and 3 pm, but no one discusses how this impacts their work and livelihood. They have to either extend their work hours to late evenings or they do not get paid for that period. This might not be a very viable solution for them,” he said.

Elections in the summer months can’t be avoided, he added, so the organisers need to make sure that there are basic arrangements made for the crowds that turn up for rallies. “Choose closed or shaded venues, have ample arrangements for water and refreshments, and avoid packing the venue more than its capacity,” he advised.

Back in Pansar, the power-packed rally—fuelled with slogans and songs—finally came to an end after a 30-minute speech by Rajnath Singh. He and his entourage departed immediately thereafter, but the villagers took another couple of hours jostling through the crowd in the suffocating heat before they could make it out of the barricaded venue.

Exhausted, Kashyap and his fellow villagers were finally ready to board their ride. He had tied his gamcha, now soaked in sweat, over his bald head for some protection against the gruelling heat. His initial enthusiasm had fizzled, but a spark remained. “Heat is seasonal, but elections only come once in five years,” he declared.

Then, they were all stuffed again into tempos for a sweaty, bumpy ride home.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)