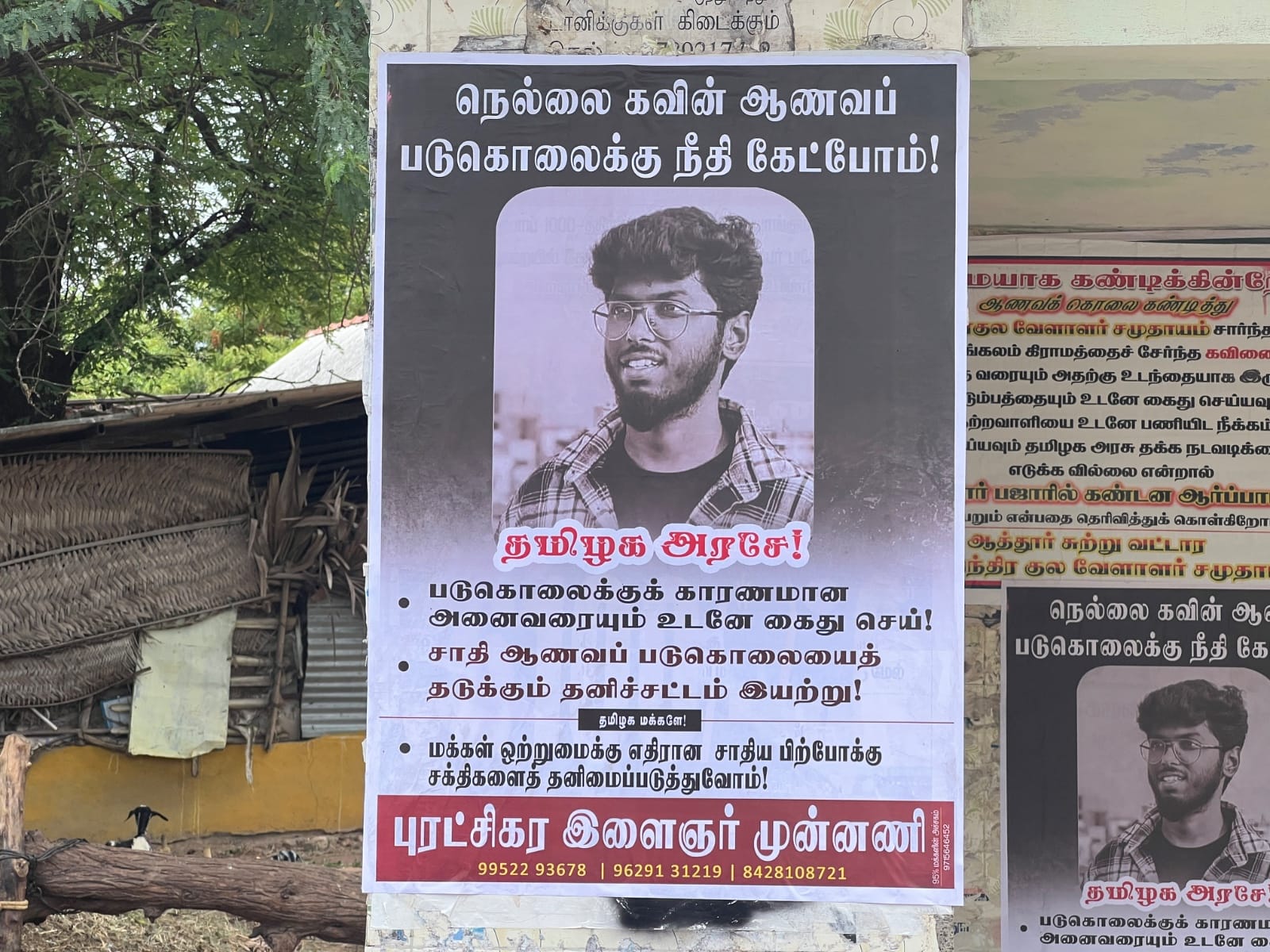

Arumugamangalam, Tuticorin: Tamilselvi sat silent and expressionless as political leaders across party lines visited her home at Arumugamangalam in Tamil Nadu’s Tuticorin district. She hadn’t eaten since July 27 — the day her eldest son, 27-year-old Kavin Selvaganesh, a Dalit IT engineer, was brutally murdered in Tirunelveli, about 40 km away.

“When Subhashini told me she was in love with my son, and that her family disapproved, I sensed the danger he was in,” Tamilselvi told ThePrint in an even tone.

Kavin was a Devendra Kula Vellalar, part of a Scheduled Caste community also referred to as Pallar. His attacker, 23-year-old Surjith — Subhashini’s younger brother — is from the Maravar community, part of the dominant Mukkulathor caste group, which is classified as Most Backward Castes (MBC) in Tamil Nadu that also calls itself ‘Thevar’.

Scars on Kavin’s face bore multiple injuries. One eye was gouged out, and his face had been disfigured beyond recognition. It’s a horrific caste murder, which are carried out in the name of caste pride and honour repeatedly. The circumstances surrounding Kavin’s death and how it occurred follows a pattern that Tamil Nadu is a little too familiar with. And the well-oiled playbook of political denial, police negligence and social cheering continues in this case as well.

In Tamil Nadu, a state plagued by caste violence and the so-called “honour” killings, the murder of a Dalit engineering graduate earning a six-figure-salary at an MNC stands out.

“Kavin broke the tropes that caste society imposes on Scheduled Caste members when they are victims,” senior journalist and writer Jeyarani said. “This is proof that caste violence has nothing to do with class…it’s a mindset that wants to grade inequality as it is.”

Tamilselvi said she had asked Subhashini to end her relationship with Kavin as her parents were against it.

“She had visited our home in Thoothukudi. When Kavin fell sick in 2023 and was in Chennai, Subhashini came to see him,” the mother said.

Friends of Kavin said the two had been close since their school days.

“He never spoke much about their relationship, but we knew. We just didn’t know what he was going through,” said a friend of Kavin requesting anonymity. “If you spot our group, you would always hear his voice over the others. He made us laugh all the time. He was the soul of our gang,” another friend added.

The day Kavin Selvaganesh was murdered

Tamilselvi showed ThePrint Subhashini’s call details, asking the family to meet her on 27 July at her clinic to treat Kavin’s ailing grandfather.

At the clinic, Surjith requested Kavin to accompany him, claiming Subhashini’s parents — both serving police officers — wanted to talk to him. Tamilselvi believes Surjith was informed of the meeting by Subhashini herself. Kavin left with Surjith while Tamilselvi and her brother continued speaking with Subhashini.

When their conversation ended, Tamilselvi said she attempted to contact her son but received no response. Subhashini also tried calling Kavin, she added, but was similarly unable to reach him.

Police said it was Surjith’s father, sub-inspector Saravanan, who first identified Kavin’s body. Officers told ThePrint that Surjith fled the scene after the murder and called his father a few streets away. By the time Saravanan arrived, the police were already present. He then identified the body as Kavin’s, and subsequently accompanied his son to the police station, where Surjith surrendered along with the alleged murder weapon.

Meanwhile, Tamilselvi said she desperately reached out to relatives and Kavin’s friends in an attempt to trace her son. About an hour later, a police officer called and asked her to come to the crime scene. When she arrived with her brother, she found Kavin lying mutilated on the ground.

“What happened for the rest of the day, I don’t remember clearly,” she said.

Aftermath and competing narratives

Two days later, Tamilselvi said she would not accept her son’s body until Subhashini’s parents were arrested. She alleged that they were complicit in instigating the murder.

The days following the murder saw a flurry of conflicting narratives. Some media reports suggested that Subhashini had denied the relationship altogether, while photos of her with Kavin began circulating on social media, along with older images of Surjith posing with a veecharuval — a long billhook machete.

On the fourth day after the murder — a day after her father was arrested — Subhasini released a video to the media. In it, she confirmed her relationship with Kavin and reiterated that her parents had no role in the killing. She said Surjith had spoken to Kavin about marriage in May, and after learning about the relationship, had informed their father. Subhashini added that when confronted by her father, she had denied the relationship. In the video, she also claimed that Kavin had asked for six months’ time to decide on marriage.

This video, which regional media circulated in parts, further complicated an already sensitive case.

As protests began, political leaders, including MLAs and MPs, visited the family and urged them to accept the body. Tamilselvi’s family finally agreed to perform the last rites on 30 July.

On the morning of 1 August, Kavin’s body was brought to his grandparents’ home in Arumugamangalam. Tamilselvi, who had maintained her composure until then, was overpowered by grief at the sight of her son’s body.

Kavin’s face was so badly mutilated that one half was covered. Tamilselvi lifted the cloth to reveal the full extent of his injuries. One eye was missing, and much of his face had been hacked and stitched back together.

Meanwhile, as word of the murder spread, unverified narratives began circulating. Local WhatsApp groups and some Tamil media reports, citing unnamed “police sources,” described Kavin’s relationship with Subhashini as “unreciprocated love”. ThePrint also spoke to journalists in the region who confirmed that members of the Thevar community within the press had spread these claims. A Tamil newspaper also reported it. These statements were then used by caste outfits to justify the killing as an act of ‘honour’.

It wasn’t until Subhashini released a video reaffirming her relationship with Kavin that the dominant narrative began to shift. Still, Kavin’s family blames both the police and press for launching a media trial against Kavin and weakening their case.

Caste violence on digital platforms

While the brutality of Kavin Selvaganesh’s murder stunned many, it was the reaction on social media that revealed a more disturbing trend in Tamil Nadu’s caste dynamics. In recent years, every time a caste killing makes the news, a new form of violence is unleashed on digital platforms, one that celebrates the perpetrators. Earlier, caste violence was amplified because of the lack of media coverage. Now, users share congratulatory messages celebrating such crimes.

After Kavin’s murder, X and Instagram have been flooded with tweets and reels lauding Surjith for his act. The messaging is two-fold. One set of users anointed him as a ‘Thevar veeran’ — a hero who had “protected the honour” of his sister and his community. Other posts portrayed him as a victim, a former athlete who had been “pushed” to take the extreme step to “defend caste pride”.

Photos of Surjith ‘Veeran’ in athletic gear were juxtaposed online with images of him holding a machete. At the same time, Kavin was subjected to character assassination, with photos of him alongside female colleagues being circulated to label him a “womaniser”.

In places like Nanguneri, these caste identities are also expressed symbolically online. Handles using photos of Muthuramalinga Thevar, a dominant caste politician credited with the coinage of the word Thevar, receive traction from other Thevar handles. Conversely, profiles celebrating Immanuel Sekaran, a Dalit political leader murdered in the 1957 Mudukulathur caste riots, receive support from Devendra Kula Vellalar handles. Muthuramalinga Thevar was arrested for Sekaran’s murder, but eventually released.

Karthikeyan Damodaran, assistant professor of social science at National Law School of India University, has written how events like Thevar Guru Poojai were used as sites to inflict a sense of domination, with attacks on Dalits common in the days leading up to the pooja. Eventually, Immanuel Sekaran Guru Poojai was instituted as a counter-symbol.

“These events have always been the centre of divisive politics, and this is to ensure that the region remains polarised,” explains Jeyarani, who has reported extensively on caste violence in the region. “Even Ambedkar Jayanti events in schools see vehement opposition from students. Teachers who are Dalit or progressive have been attacked when they try to create a safe space for such events. During these events, [dominant caste] students make expressing their caste identity the centre of their existence.”

This assertion has now shifted to social media, which allows for a faster spread of caste pride and hate speech.

The network that feeds hate online

Activists and journalists tracking caste-related violence say anti-caste posts originate from organised networks of caste-based groups active on social media. In many districts, caste outfits encourage young people to create handles that express pride in their identity.

One such group, the Pulithevar Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam, spoke about Kavin in the same way while praising Surjith.

“We condemn any such killings, but Surjith’s emotions need to be understood,” said A Velmurugan, a member of the outfit. “Any man with decency might feel forced to do something like this when faced with a situation like this. Their parents did not put so much effort into his sister’s upbringing for her to ruin her life by falling in love with random men.”

Pulithevar, an 18-century ruler, is another figure used by Thevars as a caste symbol and the outfit, according to Velmurugan, represents the interests and welfare of Thevars.

When asked about Kavin and Subhashini’s relationship, Velmurugan dismissed it as ‘nadaga kathal’ — staged love.

The term has been popularised by the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), a party that represents Vanniyars, another dominant caste. The PMK and its supporters have created a narrative that Scheduled Caste men trap dominant caste women in relationships — a concocted theory vehemently opposed by activists and inter-caste couples.

One of the early cases that sparked this rhetoric of ‘nadaga kathal’ was the murder of Kannagi, a Vanniyar woman, and Murugesan, a Scheduled Caste man. The couple were poisoned and killed by Kannagi’s family after they decided to marry against their wishes. In another case, Sathura, a Thevar woman, died under mysterious circumstances after marrying Daniel, a Dalit Christian. According to Daniel, her family had killed her by pouring poison into her ears and then claimed it was a suicide.

Periodic reports released by civil society organisations like People’s Watch and Evidence on the basis of surveys and legal interventions they’ve carried out have highlighted cases of deaths when dominant caste families disapprove of inter-caste love, the couple is either forcibly separated or killed. Several such murders have been passed off as suicides or accidents.

The PMK, under its leader Ramadoss, has used such incidents to stoke fears among dominant caste communities. This has led to Vanniyars, Gounders and Thevars forming political alliances and keep a watch on young women in their communities to prevent them from breaking the endogamous diktat of caste.

Dominant caste filmmakers have used cinema as a medium to mainstream this narrative, with funds from political parties such as PMK and right-wing groups. Tamil cinema has historically used caste symbols like handlebar moustaches, machetes, and bulls — most of which are seen as representative of Thevars. Over the last decade, Dalit filmmakers have countered this narrative by producing films that centre anti-caste assertion.

Despite inter-caste couples facing threats to their lives, successive governments in Tamil Nadu have failed to address the issue and provide protection to them.

Institutional caste discrimination — a Tamil Nadu problem

Kavin’s killing has once again drawn attention to southern Tamil Nadu, where caste-related murders barely make headlines or are debated on primetime news channels. But the assumption that such crimes are limited to the south is misleading, said Samuel Raj, general secretary of the Tamil Nadu Untouchability Eradication Front (TNUEF).

“It’s just that southern Tamil Nadu has a history of assertion against caste violence since the 1990s, so they are reported more,” he told ThePrint. “But every district in Tamil Nadu is atrocity-prone.”

Several reports have cautioned Tamil Nadu about a disturbing new trend in the past decade. People are literally wearing caste on their sleeves – as early as in school.

In December 2023, the TNUEF released a report documenting caste-based discrimination in schools across the state. The survey, which covered 644 students from Classes 6 to 12 across 441 schools in 36 districts, found that students were using caste-identifying markers such as wristbands and chains from high school onwards. It also documented incidents of untouchability by teachers and students being made to line up according to caste.

A year later, a separate report by retired judge Justice K Chandru reiterated many of these findings. Perhaps the most shocking part of that report was that district officers in most parts of the state denied the existence of caste discrimination altogether.

Activists argue that this institutional denial is deep-rooted, yet ignored and overlooked.

“Despite being home to anti-caste leaders like Iyothee Thassar and Rettamalai Srinivasan who came before Periyar, Tamil Nadu’s legacy of anti-caste reform is plagued by the reluctance of Dravidian parties to accept how they have handled caste themselves,” said Vasugi Bhaskar, writer and editor of Neelam Publications, an anti-caste publication from Tamil Nadu.

In 2019, after trainee IAS officers reported the use of caste-identifying wristbands in government schools, the Tamil Nadu directorate of school Education issued a circular directing officials to crack down on the practice. Within days, then minister for school education, K A Sengottaiyan of the AIADMK revoked the circular, publicly denying the existence of such markers.

“The main groups that have to be targeted to address the root of caste feeling are students, teachers and parents,” said Jeyarani. “But no political party wants to participate in this work.”

In public remarks, Assembly Speaker and Radhapuram MLA Appavu of the DMK dismissed caste-related clashes among students as “minor disputes,” saying they should be handled by school authorities. These comments were criticised by Justice Chandru, whose committee found widespread casteist behaviour among school teachers and principals across the state. The report also noted that, in many cases, parents of students involved in caste-based violence did not condemn the attacks.

There is also a systemic failure to understand caste violence more broadly. In a 2024 commentary published in EPW on why caste atrocities in southern Tamil Nadu continue unabated, Manikumar, a history professor from Tirunelveli, pointed out how judicial commissions such as the Ramamurthy Commission and the Justice S Mohan Commission “have approached the issue of caste conflicts from a legal angle, thereby treating each incident of caste violence as a law-and-order problem.”

In the 1997 Melavalavu massacre, a Dalit panchayat president was beheaded. Both DMK and AIADMK downplayed the seriousness of the crime by not pursuing acquittals of some of the prime accused or by facilitating early release of those convicted. Such actions have created hostility against Dalit leaders.

To this day, Dalit panchayat leaders still face resistance when asserting basic authority, and are even denied chairs to sit on during meetings. There have been instances of the cadre of the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK), which is in alliance with the ruling DMK, being denied entry in dominant caste neighbourhoods. During the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, VCK flags were reportedly excluded from events in some dominant caste localities.

From then until now, successive governments have failed to address the roots of caste violence, which has now become endemic in nature. Caste massacres witness a lackadaisical attitude because of the strong influence of dominant caste groups within the police and local administration.

Police collusion and system breakdown

In southern Tamil Nadu, caste violence has a history of collusion between the police and the perpetrators. In Kodiyankulam in 1995, an attack on a Dalit bus driver by Maravars turned into clashes between the two groups. According to a PUCL report, more than 500 police officers attacked the Dalit-dominated Pallar village, destroyed homes, and beat residents — in the presence of senior officers, including the district magistrate and the superintendent of police. No action was taken against the officers involved.

“These patterns of marginalisation create an understanding that caste crimes will receive piecemeal treatment,” said Ramesh Nathan, the Executive Director of Social Awareness Society for Youth (SASY).

Even Tamilselvi’s initial response to her son Kavin’s murder was that the perpetrators would get away. Recounting her experience at the police station on the day of the murder, she spoke about feeling nothing but distrust.

“That police station felt so hostile,” she told ThePrint. “I lost consciousness multiple times.”

The fear is not unfounded. In Kavin’s case, the hostility inside the police station was created not only by the generally apathetic attitude of the officers when dealing with victims of caste violence, but also by the presence of multiple political actors.

Tamilselvi also alleged that she was prevented from drafting her own complaint at the police station. She said lawyers affiliated with Tamizhaga Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam (TMMK) insisted on writing the complaint on her behalf, leading to errors in the FIR.

“I was very weak and in trauma. But they wouldn’t let me write what I wanted. The atmosphere inside the police station didn’t help,” Tamilselvi said.

According to civil rights lawyers, procedural lapses at the FIR stage often hurt cases later in trial. In this instance, the police commissioner told ThePrint that TMMK lawyers prevented officers from freely interacting with Tamilselvi.

“We weren’t allowed to see Kavin’s body before the postmortem. On the day of the crime, we made several requests, but the police kept telling us it wasn’t allowed,” said Essaki Muthu, Tamilselvi’s brother. This was despite a 2020 Madras High Court order mandating family access to the body for inspection and documentation. The postmortem was eventually conducted without any family member present — even though ACP Prasannakumar told The Print he had personally asked Kavin’s younger brother to attend.

Even police officers that ThePrint spoke to offered conflicting accounts of the motive. Some suggested that Surjith and Kavin had previously spoken about marriage.

“It is on the investigation agencies to figure out the motive and what triggered the murder. But that a 21-year-old felt emboldened to use the same machete that he had been flashing all over his social media with pride is sufficient to establish that irrespective of an existing relationship, these ingrained feelings of caste superiority will surface during conflict. And that is what happened with Surjith as well,” Jeyarani said.

For activists like Ramesh Nathan, the real failure lies in the collapse of institutional safeguards and the complete lack of trust in police. But this is where the role of the District Vigilance Monitoring Committee (DVMC) — mandated under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Rules, 1995 — becomes paramount.

The DVMCs are supposed to monitor caste atrocities, critically examine why they occur, and highlight loopholes preventing efficient prosecution.

“But most DVMCs are dysfunctional and do not even do the bare minimum,” said Nathan. “There is nobody to monitor their work or pull them for inaction.”

Back at Arumugamangalam, a day after the funeral, as Tamilselvi prepared for recording her first statement with the CB-CID, she seemed resolute on facing the legal fight ahead. “I will speak my truth until my son gets justice. I will make sure this ends in a conviction.”

(Edited by Prashant)

Very powerful reporting by the Print of an incredibly sad event. On the flip side, however, it should serve as a reminder to young promising Indian men. Please don’t go around throwing your lives over “love”. If indeed you wish to go for “love” marriage, please be sure that the girl’s family are OK with it. Otherwise just walk away.