Mumbai: Kausar Munir was in an auto in Juhu when the driver pointed to the ISKCON temple and declared, “That is the Sholay of temples.” Munir, a Mumbaikar and “Bandra girl”, was amused by his comparison. When writing the lyrics of Jhalla Wallah for the 2012 movie Ishaqzaade, she used a similar wordplay, ‘Aashiqon mein jiska title Titanic’—He who holds the title of Titanic among lovers.

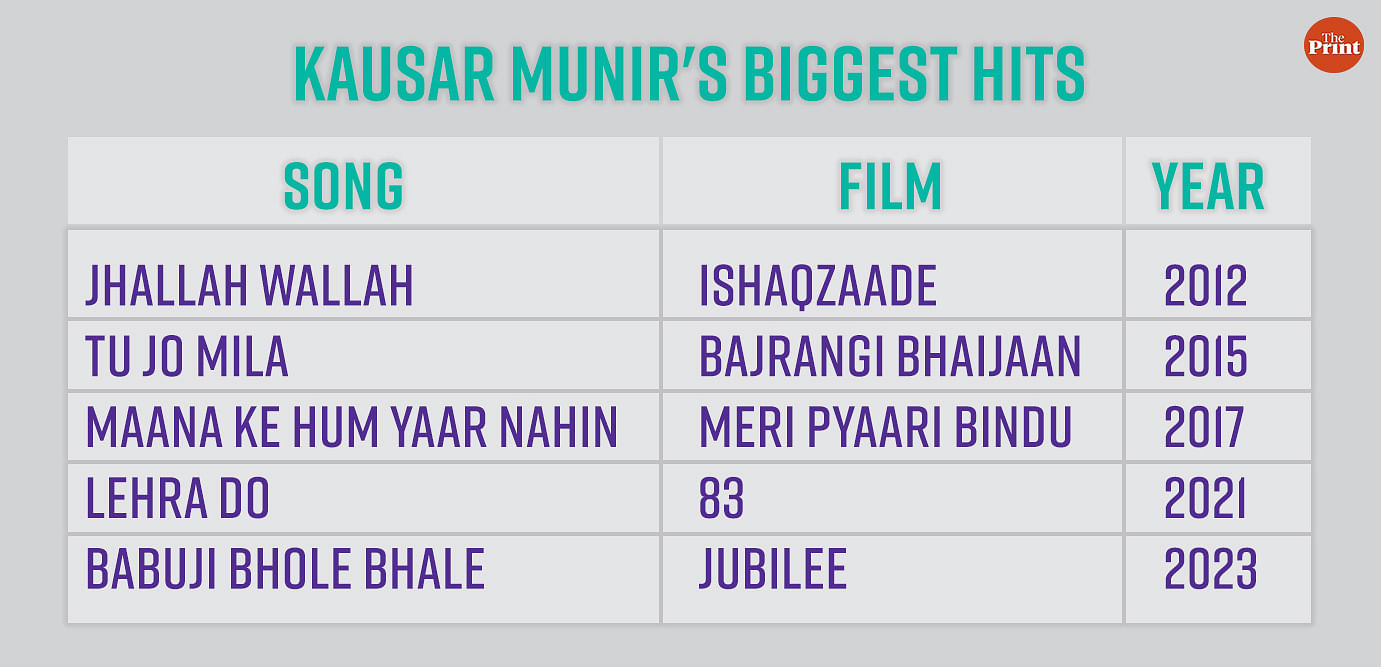

The song was a hit, but it wasn’t the one that got her a long-overdue award. Seven years after Rashmi Singh became the first female lyricist to win a Filmfare Award for the song Muskurane in 2015, Munir won it for Lehra Do in 2022. The acknowledgement both women finally got is crucial in a film industry that reveres its male lyricists and poets like Javed Akhtar, Gulzar and Sahir Ludhianvi. There’s an absence of women in this Bollywood Hall of Fame—a story of both gaze and gate-keeping.

Given the ‘behind-the-scenes’ nature of their job, lyricists in India are constantly fighting battles. It was only in 2012 that Javed Akhtar, who was a Rajya Sabha MP at the time, won the fight for songwriters, artistes and performers to receive royalty. It’s now enshrined in the Copyright (Amendment) Act. In 2020, a group of 15 lyricists from the Hindi film industry, including Munir, released a song, Credit De Do Yaar, to demand that they be given proper credit by music labels for their work. But female songwriters have to work doubly hard for fame and fortune.

The new crop of women lyricists is changing the rules, one song after another–from reimagining the item number to romance to nationalism. Their words and wit cradled

in songs of love, longing and loss, joy and jubilation. Today, Munir and Singh are joined by the likes of Anvita Dutt who turns to her experience living in small towns across India as an army child, singer and songwriter Priya Saraiya who draws from her Gujarati roots, and dialogue writer and lyricist Abhiruchi Chand who dabbled in advertising and journalism before turning to songs.

At a time when women scriptwriters and directors are delivering hits, and content hunger is unprecedented, they are fighting for acknowledgement and opportunities. It’s only now that they are being recognised.

Whether it’s Munir’s spirited sports anthem Lehra Do for the 2021 movie 83, the heart-wrenching Ranjha from Shershaah (2021) composed by Jasleen Royal and written by Dutt, or the poignant ache of Saraiya’s Kalle Kalle from Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui (2021), the lyrics are the core of the musical experiences.

“I didn’t like the term ‘female lyricists’ because you don’t use that for men. But I know there are so few of us, and it is important to talk about it and acknowledge it. So now I do talk more about it,” says Dutt.

Also Read: Alia Bhatt in Raazi to Deepika Padukone in Pathaan — female spies not just about oomph

Item numbers and female gaze

Composer and musician Shubha Mudgal questioned whether women in songs would be portrayed any differently if they were written by women. “Would and do they borrow the male voice when writing?” she asked in a column for BusinessLine. Songwriters, she concludes, follow convention, conforming largely to stereotypes created by men. Women poets on the other hand “have written of the lifting of the veil, discarding home and hearth, and rebelling against the restrictions…”

But lyricists are not writing for themselves, they are following a brief. Munir, too, has in the past admitted that if she was given a brief for an item song, she would think of all the raunchy words. She put it down to “years of conditioning”. That said, item numbers can be tackled differently by women. And that’s when the writer’s personality—and gender—comes into play.

Even though ‘item songs’ have primarily been penned to objectify women, female lyricists bring a shift in perspective.

“In Jhalla Wallah, she is a prostitute, but she is talking about love,” says Munir. Gauhar Khan performed the song, and it became one of the film’s most popular songs. “It was the hardest song to write. Habib Faisal, the film’s director, did not want it to be just another item song.”

But Munir knew she had an advantage—she is a woman.

“Even if I write an item song, it won’t be crass, crude or generic. I know how I would want people to look at me or think in terms of the female body or form.” Munir recalls her mother listening to tapes of Pakistani ghazal singer Munni Begum. She drew from that, turning the song into a mix of folk and entertainment.

Another item song that Munir had to write was for the movie Tevar (2015), but when the singer read the lyrics she backed out. In an interview with The Indian Express she said that it was probably due to the moral pressure placed on women.

Munir cites the works of Gulzar, Varun Grover and Amitabh Bhattacharya—all of whom have written “sensitive” lyrics. Bhattcharya’s lyrics in the song, Ghodey Pe Sawaar for the 2022 movie Qala, are playful but have a strong push for consent. To a large extent, this is the result of more women screenwriters and directors pushing for complex storylines with well-rounded, complex and very real male and female characters. Like the plotlines, the lyrics too are changing to reflect this.

It was a different story 20 years ago. Bollywood’s Hall of Fame in the 1990s and early 2000s was ruled by male composers and directors. Even female songwriters like Maya Govind and Rani Malik were ultimately writing not just in a man’s world, but also for the male gaze. That was the brief. Films like Darr and Jeet, were marketed as romance, but have not aged well—today, they fall clearly in the stalker zone. And by default, so do the songs.

I didn’t like the term ‘female lyricists’ because you don’t use that for men. But I know there are so few of us, and it is important to talk about it and acknowledge it. So now I do talk more about it

-Anvita Dutt

“It does make a difference sometimes who is expressing the love, or how one is doing it. There is the famous song, Aap Ki Nazron Ne Samjha, Pyaar Ke Kaabil Mujhe (Your gaze has made me worthy of your love). That is such a male perspective, and I have found it problematic. I want to avoid that narrative,” says Munir, whose love for music from the 1950s and 1960s influenced her work in Babuji Bhole Bhale and Dariyacha Raja.

Also Read: Look out for the women in Rocket Boys — Mrinalini Sarabhai, Pipsy show grit and grace

No crash course

What’s needed are more women lyricists and poets. But not many see it as a viable profession and the ones that do don’t know where to start.

“I think it has to do with the fact that there is no crash course for writing lyrics, you cannot really teach someone, and it gets that much harder to start out as one,” says Saraiya.

Even contemporary female lyricists did not really start by wanting to be lyricists. Dutt is a director, screenwriter and dialogue writer. Saraiya has a huge fan following—but her fans know her better as a playback singer.

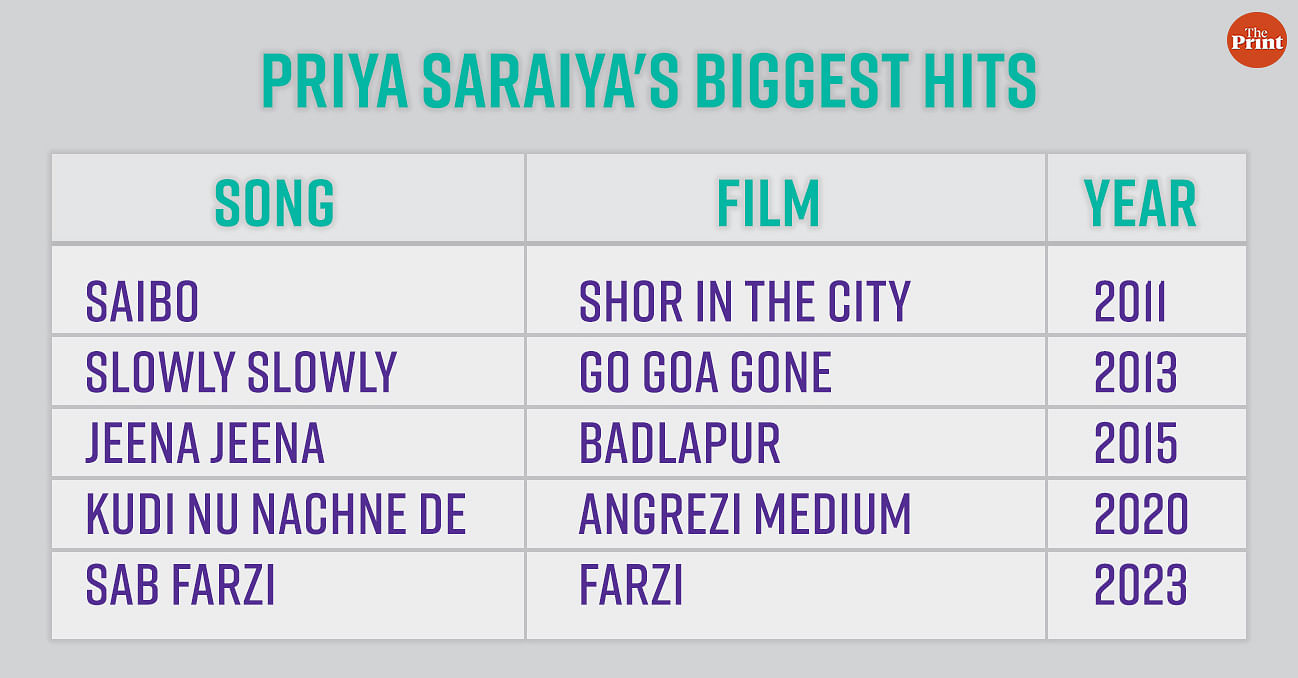

For Saraiya, who had been singing since she was five, it was a Facebook post asking for ‘work in music’ that put her on this path. She needed the money to support her family and help her father, who at the time, was the sole earning member. Music composers, producers and directors Sachin Sanghvi and Jigar Saraiya (better known as Sachin–Jigar) reached out to her for a project. She wrote a scratch with dummy lyrics in 2011—and never looked back. The song, Gale Lag Ja, was the start of a long collaboration with Jigar whom she later married. Over the years, she has written many popular tracks like Slowly Slowly from Go Goa Gone (2013) and Jeena Jeena from Badlapur (2015).

One of her most popular songs, from the early days of her career, is Saibo from Shor in The City (2010).

“Sachin and I were teasing Jigar in a mall, singing a Gujarati song, Saibo, and Jigar liked it. We ended up writing it in 20 minutes, and it got the greenlight too,” says Saraiya. That became a career-defining moment. Saibo could be heard everywhere, and despite there not being any Gujarati characters in the film, it became the film’s most popular song.

When she started as a songwriter, Saraiya found it hard to get into the ‘zone’. “I would often take an auto ride around Mumbai because it would help,” she says. Today, after writing as many as 80 songs, she no longer needs to travel the city hunting for a muse. Her latest track, Sab Farzi, has almost 6 million views on Youtube. It was written for Raj &DK’s hit show Farzi.

For nearly all of the women, entering the space of writing songs happened by accident, even though they had been writing screenplays, dialogues or poetry.

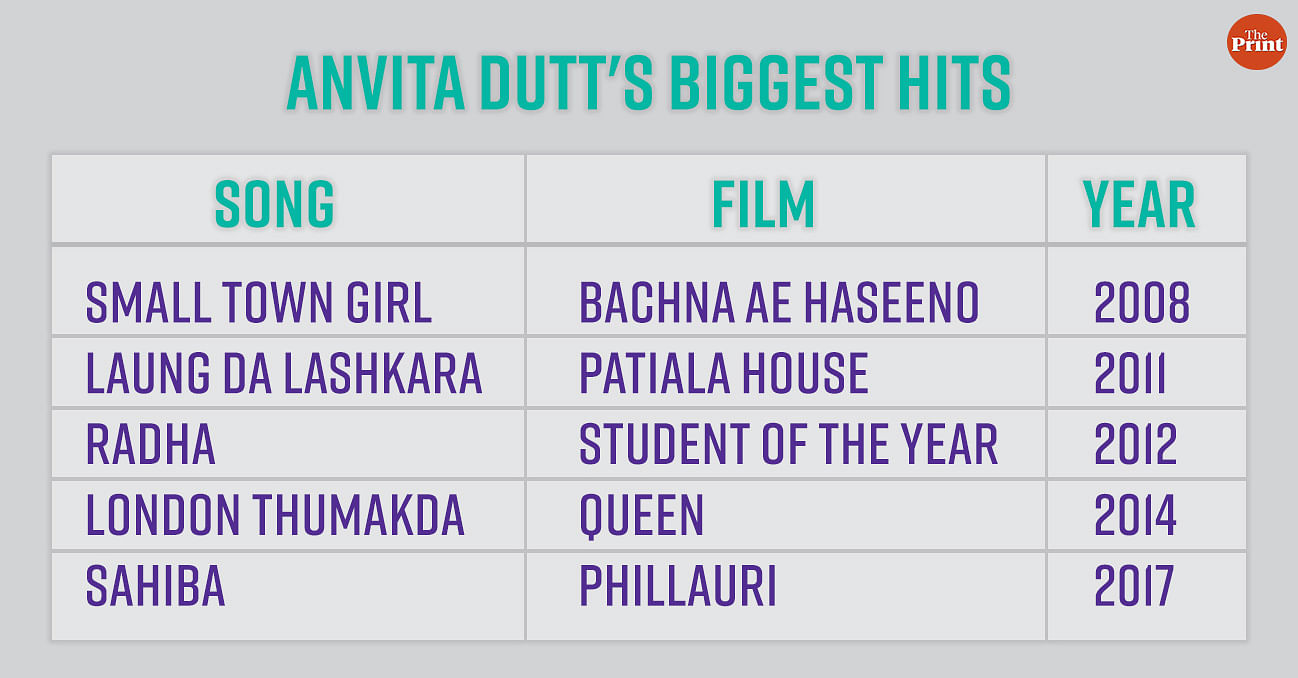

Dutt’s entry into Bollywood as a screenwriter for Yash Raj Films was serendipitous. Back in 2005, when she was at a cafe in Yash Raj Films Studios, she interrupted a discussion between her friend and another person, while they were discussing a film to point out how small-town girls actually think and talk. Aditya Chopra, whom Dutt didn’t notice sitting at a table nearby overheard the conversation and offered her the job as a screenwriter with YRF. A year later, Chopra roped her in as a lyricist for Bachna Ae Haseeno (2008).

“He said, ‘You are a lyricist’, and that was that. I told him, you need to stop announcing it,” recalled Dutt, who ended up writing the song Small Town Girl for the movie.

It was a lucky coincidence that her first hit song was about the same thing that got her the job in the first place.

“I was saying that every small-town girl is unique, and they have had to go through many things to be who they are, and it became part of the song,” says Dutt, who went on to write foot-tapping numbers such as Radha from Student Of The Year, Laung da Lashkara from Patiala House, London Thumakda from Queen, and melodies such as Sadka Kiya from I Hate Luv Storys.

Also Read: Male gaze has met its match. Women writers are rewriting Bollywood, Aarya to Rocky Aur Rani

The battle for credits

Fans do not stop female lyricists in the middle of the road to say they love their songs—because people barely know them, see them or hear them.

At a gettogether in Mumbai at a friend’s house, the wife of a colleague once played Dutt’s song, and danced to it, without realising that she was standing next to the woman who wrote it. “It was her husband who then said do you know she (Anvita) has written the song, and then she was nonplussed,” says Dutt.

This was true for lyricist Maya Govind as well even though she wrote songs for some of Bollywood’s more popular movies in the 1980s and 1990s. Her hits include Maine Payal Hai Chhankai and Main Khiladi Tu Anari.

Even a cursory glance at the history of Filmfare Awards shows that female lyricists were not regularly nominated for their work until Singh and then Munir. The first nomination for a female lyricist came in 1978, almost 20 years after the awards first began, for Preeti Sagar. She was nominated for Mero Gaam Katha Parey from the film Manthan.

Then 13 years later, in 1991, Rani Malik was nominated for the hit song Dheere Dheere from the Rahul Roy-Anu Aggarwal starrer Aashiqui. But she lost to Sameer, who wrote Nazar Ke Saamne.

“Visibility is important. Girls want to be a Lata Mangeshkar or an Asha Bhonsle because they know who these people are. But the same is not true for composers of lyricists,” says singer, songwriter and composer Jasleen Royal.

For songwriters—men and women—awards propel virality. They help lyricists demand better pay and give a boost to the fight for proper credit. Unless a person wins an award or has multiple ‘hit’ songs, the credit is in the third or fourth line of the description under a YouTube video. On music streaming apps, they might not even be mentioned if there is more than one composer or lyricist. It was only in 2018 that Spotify started showing songwriting credits.

“The lack of credit is not just about not having our name next to the work we have written, it is also loss of royalty, of money we deserve,” says Dutt.

Giving song credits in India is at best inconsistent, and unless it is a single, it is difficult to find songs by the lyricist’s name. Even in YouTube videos of a particular song, actors are credited first, followed by singers, music directors/composers, followed by lyricists.

Visibility is important. Girls want to be a Lata Mangeshkar or an Asha Bhonsle because they know who these people are. But the same is not true for composers of lyricists

– Jasleen Royal

“It can be tricky in India, because many people are involved in a song sometimes, and someone loses out in that situation,” says Saraiya.

On top of the struggle for credit, is ownership of the songs, which are exclusively owned by music labels.

“I have a reputation of putting my foot down and demanding my due, in money and credit. I had done it even when I started out,” says Royal, who was part of the seven-composer team that won the Filmfare Award for Best Music Director for Shershaah.

Ownership also helps labels re-create and remix popular songs, a practice that first became wildly popular in the early 2000s with remixes by DJ Suketu. The practice has regained momentum in the last five years with numbers like Masakali from Delhi 6 (2009) being re-recorded in 2020.

“Once the song is written, it is out of the lyricist’s hands,” says Dutt, who is preparing to direct her third film.

Collaboration, community and big plans

Lyricists share a deep respect for each other. Varun Grover, Swanand Kirkire, Amitabh Bhattacharya, Munir and Dutt are best friends.

“I got them to write a song each for my film Qala, and we also send work each other’s way,” says Dutt, adding that lyricists don’t usually write just one song for a movie.

She met Bhattacharya on the steps of YRF, and he led her to the others, and it became a tightly-knit group.

With the community being so small, there is no sense of cutthroat competition. The camaraderie has also helped them push each other, and even fight for each other.

“I asked that Anvita be a part of the video of Ranjha too. Why can the songwriters not be part of the video, or be given due credit,” says Royal.

Credits and regular work are crucial for getting paid, and on time.

“We look out for each other, on good and bad days, we collaborate and work with each other. We have dinner every other week, and that is how we have also survived,” says Dutt. “For a job like this, you need that.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)