Bengaluru: In upscale Koramangala, the pincode of Bengaluru’s tech billionaires, a new kind of philanthropy is brewing. The old culture of wealthy families supporting temples and schools is giving way to research into one of science’s final frontiers—the human brain.

“I decided to look at the brain because I felt that it’s close to computer science, which is my area of work and knowledge,” said Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan, contemplating his philanthropic journey in a conference room at Pratiksha Trust, the foundation he set up to direct his massive wealth.

Indian philanthropy is changing, two decades after Corporate Social Responsibility was made mandatory by the government. While many companies continue to spend on schools, NGOs, girl-child empowerment, toilet construction, and women’s self-help groups, a new Bengaluru wave of first-generation science and tech billionaires is quietly changing the grammar of giving. It’s a shift that’s mirroring the nation’s expanding aspirations.

Gopalakrishnan is part of a growing group of India’s first-generation entrepreneurs who are building their legacies much like the Tatas did in India, the Rockefellers and Fords in the United States, and the Rothschilds in Europe. They’re deploying their money in the pursuit of more ambitious goals—promoting science, arts, and institution building. Tech entrepreneurs increasingly see knowledge as the most valuable currency.

For Gopalakrishnan, funnelling hundreds of crores into brain research and neuroscience is a step towards finding a cure for debilitating diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

With Rainmatter Foundation, Zerodha founder Nithin Kamath is supporting climate action. The Nilekanis opened their philanthropic war chest to launch EkStep Foundation—a one-stop, open-source digital public infrastructure for education and upskilling. Biocon founder Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw is backing both scientific research and art galleries.

Seventy-one per cent of philanthropic families currently give to historical causes such as education and healthcare, according to the India Philanthropy Report 2025. This is followed by gender, equality, diversity, and inclusion at 40 per cent. Only around 29 per cent fund climate action, while 23 per cent support skill development. The new billionaires are bucking these trends. Unencumbered by the baggage of generational wealth, they’re building art galleries and start-up incubators. They’re betting on scientific research and knowledge-building infrastructure.

“Because they have earned the capital themselves, first-generation entrepreneurs are less concerned about legacy,” said Deval Sanghvi, co-founder of Dasra, a Mumbai-based strategic philanthropy organisation that brings out the annual report. “With multi-generation families, there is a sense that the family name needs to be carried forward.”

This new-age philanthropy is changing conversations around wealth as well as the physical contours of Bengaluru. The city is now home to a Science Gallery, the Museum of Art and Photography, and the well-established NSRCEL, which supports early-stage ventures in climate, agriculture, education, and healthcare.

“What makes Bengaluru unique is that we have leveraged academia, industry, startups, and the government to shape policy and enable the creation of an ecosystem,” said Mazumdar-Shaw. “It’s a sense of purpose and national pride that makes us invest in areas of interest that we think can impact, influence, and transform India.”

Also Read: Bengaluru is leading India’s mental health revolution. VCs say it’s the next big field

From Aadhaar to EkStep

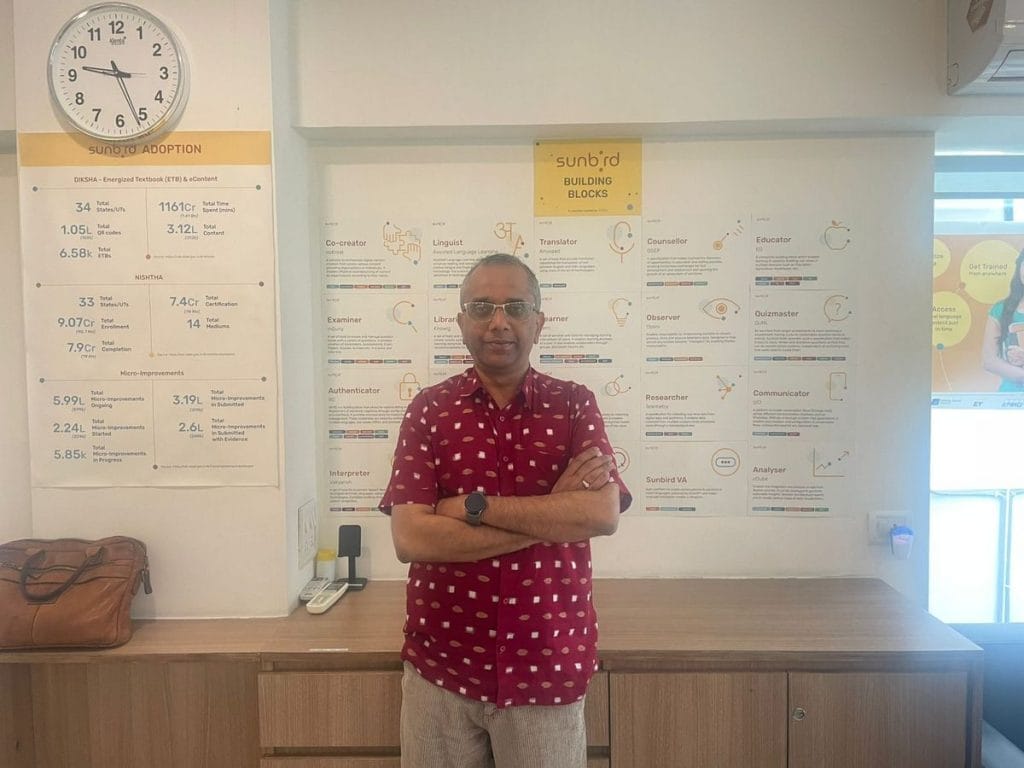

A digital assistant answers Shankar Maruwada’s phone, replacing traditional voicemail and streamlining his packed schedule. It’s just one glimpse into how deeply technology shapes his life. At EkStep Foundation, which he co-founded with Nandan and Rohini Nilekani, the focus is on building digital infrastructure designed to operate at scale, not just for personal use.

“Given that our funding is internal, we can afford to think long term,” said Maruwada, at his startup-inspired, minimalist office in Bengaluru. It’s in Koramangala’s 4th Block, the same neighbourhood as Gopalakrishnan’s Pratiksha Trust. There’s a reason why the area earned the nickname ‘Billionaire Street’.

The culture of giving prevalent on this street sways closer to the American style of philanthropy—something the Tatas had also perfected in earlier decades of Indian nation-building, with institutions such as the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and Tata Memorial Centre in Mumbai. The Birlas, meanwhile, mostly constructed temples and hospitals, but also set up the prestigious Birla Institute of Technology. Over the years, corporate giving in India became more about ticking the CSR box—adopt a village here, install a water handpump there.

“There is a greater maturity happening in the CSR space, where companies are realising the need for long-term grants versus one-off donations,” said Dasra’s Deval Sanghvi. “They recognise the need to support the management, the systems, processes, data and tech.”

Maruwada has a backstory for why Bengaluru became a sandbox for testing philanthropic innovation—and it goes back to the era of the Maharaja of Mysore.

“The Maharaja gave land for the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Hindustan Aeronautics Limited’s factory. He actively promoted the setting up of academic institutions and industries,” Maruwada said. Over time, an ecosystem took shape. “The idea of being generous is part of the culture here. Wealth is treated lightly—people don’t show it off.”

After my work on Aadhaar and UPI, I realised there is a lot of high-impact work you can do with technology. Most of my philanthropy is long-term, strategic in nature—whether that is supporting institutions like IIT Bombay or developing digital public infrastructure

-Nandan Nilekani

Nandan Nilekani pointed to another marker of this culture: the Indian signatories of Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge, a commitment to donate more than 50 per cent of one’s wealth to philanthropy.

“All the signatories are from Bangalore,” said Nilekani, listing out a slew of names including himself, Nithin Kamath, and Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw. “It shows that there is something here which makes people believe that they have a role to play.”

Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy’s son, Rohan Murty, has also deployed the family’s philanthropic funds in both science and culture. In 2010, he founded the Murty Classical Library of India at Harvard University, and in 2015, donated $1 million to a robotic astronomy project in the United States.

Maruwada and Nilekani knew from their experience with Aadhaar that building technology platforms at scale would require significant investment. Philanthropy, for them, offered the ideal solution: patient capital with the flexibility to take bold, long-term bets.

“After my work on Aadhaar and UPI, I realised there is a lot of high-impact work you can do with technology,” said Nilekani, adding that he felt he could make a difference by leveraging his knowledge as a co-founder of a tech company. “Most of my philanthropy is long-term, strategic in nature—whether that is supporting institutions like IIT Bombay or developing digital public infrastructure.”

Established in 2015, EkStep was designed to build technology that other organisations could plug into. This idea gave rise to their core digital platform: Sunbird.

Originally meant to improve India’s school education system, Sunbird’s modular, open-source architecture allowed it to be repurposed in unexpected ways, like one giant Lego project. The most visible outcome of the platform is DIKSHA, launched by the Ministry of Education to train teachers, teach students, and monitor learning outcomes.

“We also partnered with the Department of Personnel and Training to develop a DIKSHA for civil servants, which has now trained over 10 million government officials across the country,” said Maruwada.

Though DIKSHA was initially run by EkStep Foundation, the platform has since been handed over to the government—a deliberate long-term strategy to allow it to grow and evolve. EkStep even documented this philosophy in a thin yellow book titled Seed to Forest, symbolising the journey of a small idea into a wider ecosystem.

Thinking big on brain research

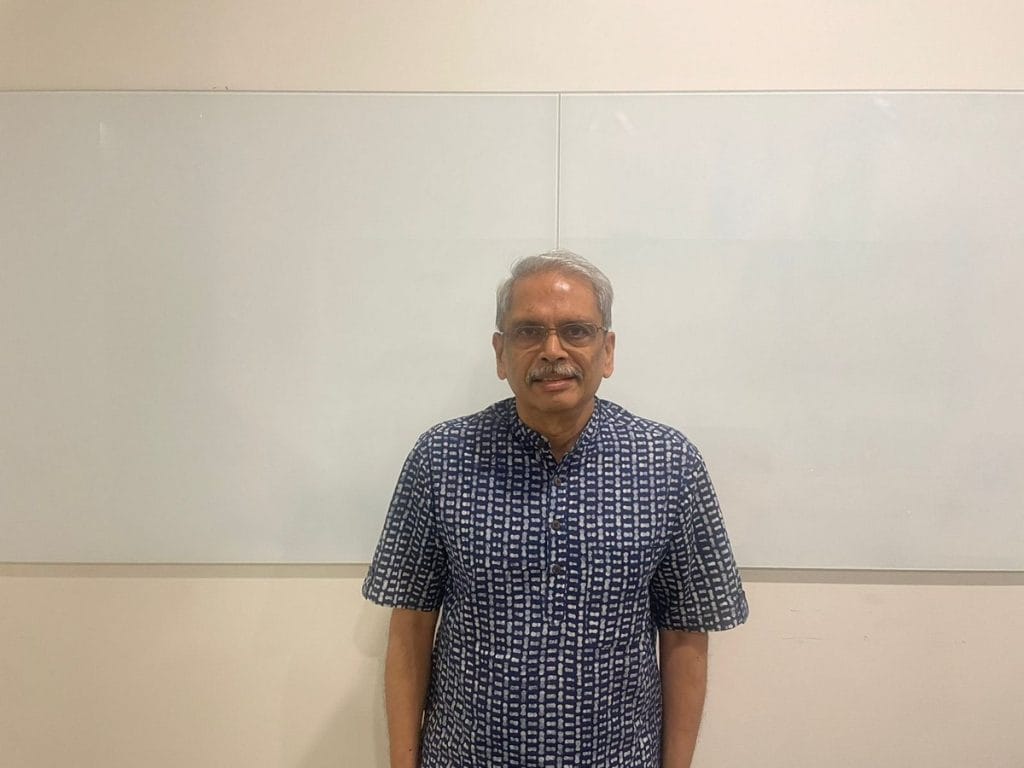

Kris Gopalakrishnan’s investment office in Koramangala mirrors his philanthropic philosophy—understated, purposeful, and functional. A large conference room dominates the space, with whiteboards covering an entire wall for brainstorming ideas. There are no life-sized models of the human brain, no posters detailing his donations, and no visionary inspirational quotes. But since 2014, Gopalakrishnan has donated hundreds of crores toward brain research.

“My purpose when I stepped down from Infosys was to help the research and innovation ecosystem in India,” said Gopalakrishnan, dressed in a blue and white Chinese-collared shirt. “And I felt that computer science is at a crossroads—we need new models and to create new capabilities in India.”

Gopalakrishnan is fascinated by the human brain, its neural networks, and how the effort to understand it helped give rise to computer science. He recounts the work of English mathematician George Boole and Hungarian-American polymath John von Neumann, both of whom laid the foundations for modern computing.

This inspiration led him to focus his philanthropy in two directions: developing new models of computing and addressing neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, especially as the world’s population grows older. Once his priorities were clear, he began identifying where the money should go.

“IIT Madras was a natural choice because that’s my alma mater,” said Gopalakrishnan, who helped fund the Sudha Gopalakrishnan Brain Centre and the Centre for Computational Brain Research at the university. “They have created a full 3D image of the brain at a cellular resolution. The next nearest brain image is one-tenth the resolution.”

[The US has] been investing in research from the 1960s, and are seeing the fruits of that today. But once you have created that ecosystem, it will produce results every year. It’s a virtuous cycle— the returns will feed in and create more money, resources, and culture

-Kris Gopalakrishnan

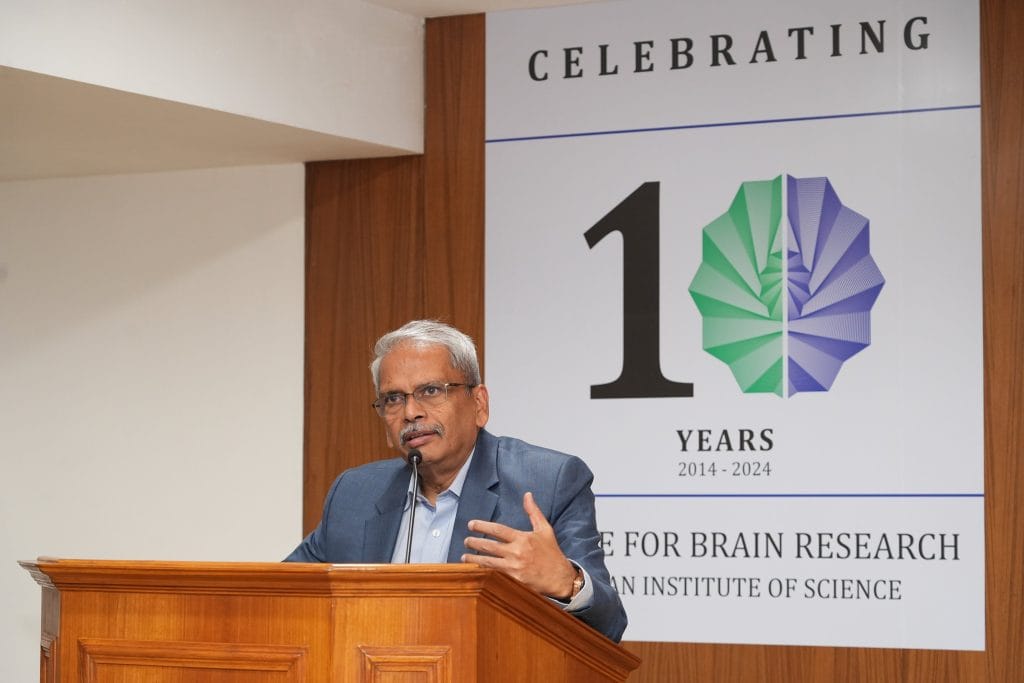

The second institution he chose was IISc in Bengaluru. In 2014, he committed Rs 225 crore over ten years to set up the Centre for Brain Research (CBR), topping it up with an additional Rs 450 crore in 2023. Back then, IISc’s neuroscience work was limited to animals. His donation allowed the institute to focus their research on the human brain.

The flagship initiatives at CBR include studies aimed at identifying risk and protective factors for dementia and other neurodegenerative conditions in India’s ageing population. Gopalakrishnan’s funding has also helped the institute attract talented neuroscientists, clinicians, and engineers.

“Multimodal data collection is ongoing, and analyses are expected to provide insights into population-specific patterns in cognitive decline and dementia risk,” said Prof KVS Hari, director, Centre for Brain Research. “The donation has placed CBR in a unique position to lead innovative and long-term approaches to ageing brain research.”

But even as science gains momentum, traditional philanthropy still matters in a country like India.

Still a need to build the basics

A toilet or school construction initiative offers a quick, tangible, and visible outcome. It’s the quintessential photo-op. That’s why many companies and business families direct CSR funds toward high-visibility infrastructure, often in the constituencies of political leaders.

Sujanpur village in Amethi, for instance, started receiving an influx of CSR funds after it was adopted by then Union Minister Smriti Irani, including Rs 9.2 crore from Hindustan Aeronautics Limited for building roads and drains.

Even otherwise, CSR funds and philanthropic donations usually flow toward basic infrastructure like roads, schools, and hospitals since these facilities are often lacking, especially in rural areas. Social development is still a work in progress, and legacy philanthropic families like the Tatas, Birlas, and Jindals recognise this. Tata Trusts, for instance, supports programs ranging from digital literacy and financial inclusion to disaster relief and skill development.

And it’s not just the multi-generational behemoths.

Despite his status as a first-generation entrepreneur, Wipro founder Azim Premji also focuses much of his charitable donations on grassroots initiatives: public education, healthcare, and livelihoods. His foundation operates field institutes across multiple states, funds over 900 civil society organisations through grants, and runs Azim Premji University with campuses in Bengaluru and Bhopal.

“A key inspiration for Mr Premji was his mother, who ran a charitable hospital for polio-affected children from the 1940s, when they were not as rich,” said Sudheesh Venkatesh, chief communications officer at Azim Premji Foundation. “Even the university has a social purpose—all its programs are toward preparing students to contribute to society.”

Conventional wealth is more family oriented, where they want to grow the name. And of course they have done a lot of work in education. But we are supporting new kinds of initiatives and programs. We… want to create an ecosystem that positively impacts the country

-Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw

Wipro Foundation, which handles the company’s CSR funds, focuses on foundational enablers like childcare and early education. While it operates separately from the Azim Premji Foundation, the two often work in parallel.

“We invest in the infrastructure of government schools, while Azim Premji Foundation focuses on classroom teaching and learning practices,” said Narayan PS, managing trustee of the Wipro Foundation, pointing out that this way, two parts of the problem are worked upon. “We’ve even built laboratories, toilets, and the foundation of entire school buildings because of structural problems.”

Unlike traditional philanthropy, the gains from scientific research can take decades. Gopalakrishnan pointed to the United States as an example.

“They have been investing in research from the 1960s, and are seeing the fruits of that today,” he said. “But once you have created that ecosystem, it will produce results every year. It’s a virtuous cycle— the returns will feed in and create more money, resources, and culture.”

Investing in India’s scientists

The sentiment of ecosystem building is at the heart of how new-age entrepreneurs approach philanthropy. Gone are the days of one-time donations and quick fixes that served as bandages over deep cracks in the system.

“When I started my company in 1978, most people wanted to pursue their careers in the United States or Europe,” said Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, recalling her early days at Biocon. “I realised that one of the things we need to make an impact in our country is to invest in science and advanced research. That’s something that resonates with my philanthropy.”

Mazumdar-Shaw, India’s first self-made woman billionaire, wants scientists to feel excited, inspired, and part of the global research landscape, so they don’t feel the need to leave India. But this isn’t just an aspiration. She’s putting her weight behind a range of research projects, both at home and abroad.

In 2019, she donated $7.5 million to the University of Glasgow in Scotland for the construction of a research centre. The gift, the largest the university had received, was also used to advance research in cancer and molecular pathology. The university later renamed the building in her honour.

Now, in partnership with the Karnataka government, she’s also working to democratise science through Science Gallery Bengaluru. It’s all part of her grand plan to create a vibrant, science-driven ecosystem.

“The Karnataka government is very open to new ideas,” she said, singling out former Chief Minister SM Krishna and his IT Secretary Vivek Kulkarni for bringing industry leaders in early to shape technology policy. The result was the creation of Vision Groups on biotechnology, IT, startups, and animation and visual effects.

“No government, irrespective of political party, has tried to change this,” Mazumdar-Shaw added.

CSR boost for startup incubator

Beyond one of the gates of IIM Bengaluru stands a nondescript grey building that houses the institute’s incubation hub—the Nadathur S Raghavan Centre for Entrepreneurial Learning (NSRCEL). Set up in 1999 through an endowment by Raghavan, another Infosys co-founder, the incubator has in recent years begun receiving CSR funds to support its programs.

“We are expected to be financially independent,” said CEO Anand Sri Ganesh, adding that the incubator is a wholly owned subsidiary of the university but operates as a separate legal entity.

Around 80 per cent of the incubator’s operating expenses now come from CSR funds. Companies such as Hindustan Unilever, Capgemini, and Kotak Mahindra Bank put in money here to support startups across a variety of industries—from electric vehicles and last-mile mobility to social enterprises and women-led businesses from tier-two and tier-three cities.

Building a startup ecosystem has long-term development impact, as opposed to the balance 99 per cent of CSR funds which go to grassroots development work—which has a high risk of regression and limited long-term residual value

-Anand Sri Ganesh, NSRCEL CEO

“Companies’ CSR teams are very lean in nature,” said Lekhya Reddy, engagement manager at Sattva Consulting, a Bengaluru-based social impact and CSR advisory firm. “So, you need an intermediary who will spend time mentoring startups, connecting them to investors. That’s the role incubators play.”

That support from corporate houses wasn’t always available. It was amendments to the Companies Act in 2018 and 2021 that unlocked CSR funding opportunities for incubators across the country. Previously, only tech incubators housed in Central government-approved academic institutions were eligible for CSR funds. But even now, the pipeline is thin.

“Less than 1 per cent of CSR money flows into the incubation ecosystem in the country,” said Ganesh, cheekily adding that his funding needs are larger than the size of the CSR market itself. “Building a startup ecosystem has long-term development impact, as opposed to the balance 99 per cent of CSR funds which go to grassroots development work—which has a high risk of regression and limited long-term residual value.”

Ganesh is also up against a bigger problem: the CSR system’s demand for visible, quantifiable results within a financial year. Startup progress, he argues, cannot be boxed into that time frame.

“We work on foundational change, which is multi-year in nature,” he said. “Unlike taking CSR funds to build a lab, where you can physically show the building, it’s difficult for me to demonstrate material impact in a 12-month timeframe.”

Despite these challenges, NSRCEL has an impressive roster. Inside its glass-walled rooms, early-stage startups are busy working on business models, fundraising strategies, and marketing plans. Over 3,000 ventures have been incubated here, with a combined valuation of more than $7 billion.

Personal care brand Paradyes, corporate volunteering platform Goodera, and social enterprise Mitti Café all started their journeys at NSRCEL. Last financial year, startups incubated here raised close to Rs 135 crore—all because larger corporates decided to take a bet on developing the ecosystem.

Also Read: Let’s talk about red tape, cash flow, say Indian startup founders

Art, culture, and capital

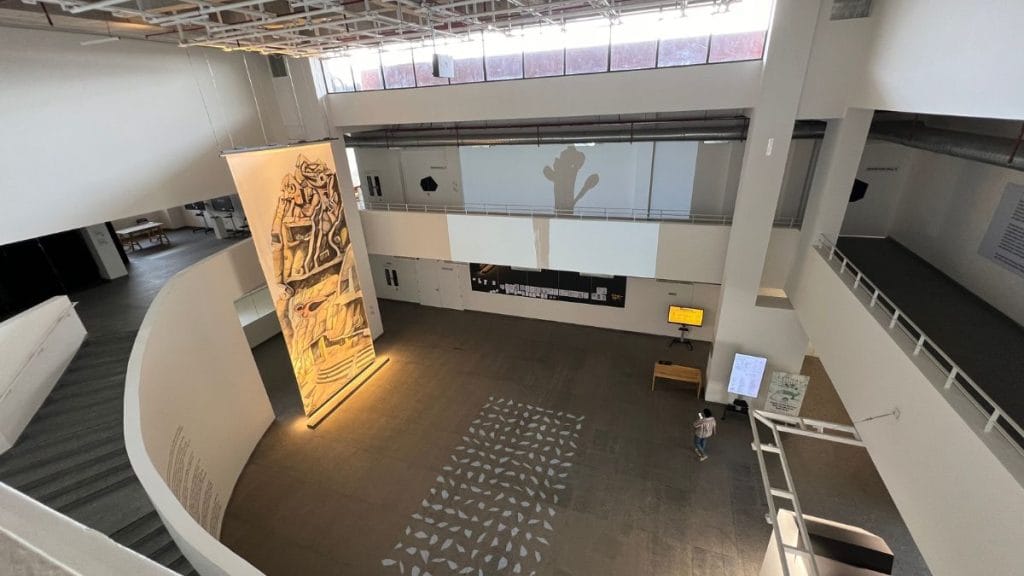

A large rock installation commands attention in the waiting area of the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), a box-like building opposite Bengaluru’s Cubbon Park. Inside, a group of college students makes their way to a gallery that explores the representation of women through sculptures, paintings, textiles, and posters.

“MAP is an experiment. It’s a very entrepreneurial, new way of showcasing our heritage, past, art and culture,” said Mazumdar-Shaw, one of the museum’s founding patrons. “We wanted to get people interested in Indian art and culture.”

Philanthropists aren’t just supporting causes linked to their entrepreneurial journeys. Despite Mazumdar-Shaw’s wealth coming from biotechnology and her support for scientific research, a significant portion of her giving is driven by her passion for the arts. Apart from supporting Science Gallery and MAP in Bengaluru, she recently commissioned Spanish sculptor Jaume Plensa to create a public installation in the city.

In Delhi, the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, inaugurated in 2010, was India’s first private museum of contemporary art. Backed by the Shiv Nadar Foundation—the philanthropic initiative of HCL Technologies founder Shiv Nadar—it now houses over 10,000 works.

The arts haven’t just attracted first-generation billionaires. Founding patrons of MAP also include Sunil Kant Munjal, chairman of Hero Enterprise, along with Tata Trusts and Jindal Stainless, organisations founded by India’s earliest industrialists. In Mumbai, Nita Ambani and the Reliance Foundation inaugurated the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre (NMACC) in 2023, which regularly hosts public installations and global performances. Delhi’s Sunil Munjal also founded the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa.

But social causes still receive a vast majority of philanthropic and CSR funding—a reminder of how much more work is required in education, skilling, healthcare, and other fundamentals. According to the India Philanthropy Report 2025, social sector funding reached an estimated $300 billion in financial year 2024, with 95 per cent coming from the public sector. Yet, this is still $170 billion short of what NITI Aayog estimates is needed.

The new-age culture of philanthropy has much to do with the development direction of the country. Fifty years ago, inadequate infrastructure in India created the need for more schools and hospitals. Today, that base layer is mostly in place, driven by rapid development and higher government tax collection.

“Conventional wealth is more family-oriented, where they want to grow the name. And of course, they have done a lot of work in education. But we are supporting new kinds of initiatives and programs,” said Mazumdar-Shaw. “We are not trying to build our name but want to create an ecosystem that positively impacts the country.”

At IIM Bengaluru’s NSRCEL, young bespectacled employees scuttle between rooms and the coffee machine, supporting the incubation centre’s startup ecosystem. One of its biggest success stories is Amagi Media Labs, a media-tech company that became a unicorn—valued at $1 billion— in 2022.

But Ganesh is just as proud of the rest. “I have no favourites among my children,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)