Guwahati, Aizawl, Churachandpur: The screams of the Kuki-Zomi men in the SUV cut through the silence of the forest at night. “Whoa, whoa… Stop, stop!” Thangboilal Vaiphei and Andrew shriek, their heads banging against the metal roof of the Tata Sumo as it hits a bump and grinds to a halt on National Highway 102B. The cartons of medical supplies, grain and essential items wrapped in blue tarpaulin sway dangerously, and the van threatens to turn turtle.

There is no signboard, no street light, just the slender ribbons of silver from the crescent moon that slice through the pitch-black forested area. The NH 102B is the only safe route for the displaced Kuki-Zomi who want to return to Manipur and pick up the remains of the day. For Thangboilal Vaiphei and Andrew, the road isn’t just taking them home. It leads to their long-delayed medical degrees. They don’t want to escape the madness and rebuild their lives in another corner of India but rather serve their community as healers.

But the journey is more treacherous than the exam itself. Every bump on the road is a reminder of time lost.

“We would have been in our internship. Our Meitei counterparts have moved forward, but we are still stuck,” says Andrew.

When ethnic violence broke out between the Meiteis and Kuki-Zomi in Manipur in May 2023, the two students were studying at Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences (JNIMS) in Imphal. They dropped everything and fled. Vaiphei went to Guwahati in Assam, and Andrew to his hometown in the Kuki-Zomi district of Kangpokpi in Manipur. By September, 175 Meitei and Kuki-Zomi people had been killed in the violence, and around 50,000 were displaced from their homes.

Andrew and Vaiphei can’t return to Meitei-dominated Imphal. But they need their medical degrees to become doctors. After protests by Kuki-Zomi students, the National Medical Commission (NMC) in November granted authorities in Manipur permission to allow displaced medical students to take online or hybrid classes and examinations at Churachandpur Medical College (CMC).

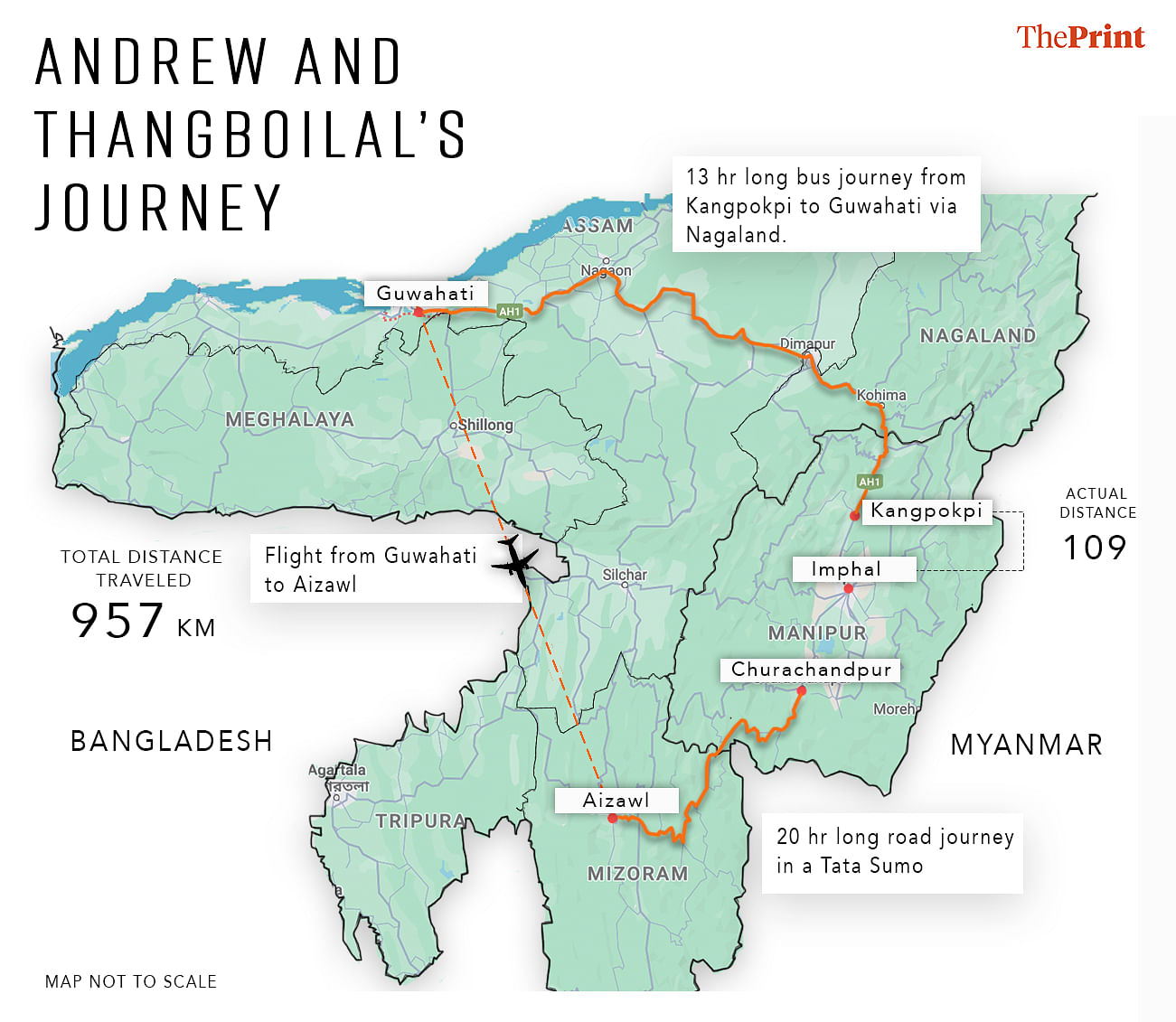

And so, they’re taking the circuitous route from Assam to Mizoram and then back to Kuki-Zomi-dominated Churachandpur. Here, they will be able to continue with classes online, and hopefully give their fourth-year final semester medical exam.

In times of peace, they could take the 109-km/three-hour ride from Kangpokpi to Churachandpur. “If we take the direct route, we will be killed by the Meiteis,” says Andrew. He has to travel nearly 957 kilometres and cross three state borders.

Neither he nor Vaiphei wants to talk about the violence they witnessed or the constant fear that—worse still—their parents will be killed.

“Growing up, we never saw Meiteis as any different from us, never imagined that our years of friendship would end on this. We don’t talk anymore. Some of the [phone] numbers are blocked; there is weird awkwardness between us. It will take generations for this to go away,” says Vaiphei.

Also read: Karnataka women are on non-stop joy ride. Backpacking to temples & palaces on free Shakti

Broken friendships, careers in limbo

Vaiphei—his friends call him Boi Boi—is still coming to terms with the events of the last nine months. As children, both men saw Imphal as a stepping stone to success, completely different from their remote hometown. When they got into JNIMS four years ago, they were ecstatic.

They miss college life—weekend games of football, bonding over their hectic schedules, and sharing dreams of becoming doctors. Andrew can’t fathom how to rebuild friendships after so much hate and anarchy.

“I had a lot of Meitei friends. We never wanted the violence that snatched our friends away,” says Andrew. “We do not know what to talk about.”

Vaiphei deflects personal questions. “Why do you want to talk about my family? We fled, and now we are safe. Talk to the families who have lost their loved ones in the conflict.”

When the violence broke out in Imphal, he took refuge in the Bir Tikendrajit International Airport and flew to Guwahati. His family is safe for now; others weren’t as lucky.

All six passengers in the SUV lapse into silence reflecting on the lives lost and broken dreams. But not for long.

“See, another indigenous food item,” Vaiphei jokes, digging out sticks smeared with red paste. “Have this, eat it slowly, this is indigenous to tribals. It’s a mango pickle—sweet, savoury, sour…tasty. Let the taste buds feel this indigenous miracle,” he says with a grin, emphasising ‘indigenous’. He laughs and pulls out more such delicacies—chuckling to himself almost as if he has the punchline to a joke nobody knows.

Hours later, he explains his fascination with ‘indigenous’.

“We call ourselves Indigenous; our tribes have origins in these hills. But the Meitei term us illegal immigrants. They look down on us.”

The journey back

Andrew, who was with his family in Kangpokpi district all these months, cannot simply hop into a car or taxi or bus for the two-three-hour journey to Imphal. Instead, he takes a bus to Guwahati via Nagaland—“I had to pay Rs 1,600”—where he joins Vaiphei.

On a cold and foggy morning on 16 December, the two friends take a car to Guwahati airport from where they will catch a flight to Aizawl in Mizoram.

As the Assamese driver starts the engine, Vaiphei turns to Andrew. “Lein, will you please keep an eye on the GPS,” he says. (Lein is Andrew’s nickname.)

The winter fog descends on Guwahati, and the car slows to a crawl. In their blue surgical masks, the friends occasionally look out of the windows. “I think your bus took that bridge when you were coming from Kangpokpi,” Vaiphei points to a flyover.

This is only the second time they’ve travelled on a plane—the first was in May 2023. It was also the first time they left their home state.

“My second flight is back to Manipur, my first was out of my state,” says Andrew without a hint of irony, as he boards the plane. As Vaiphei chats with fellow passengers, Andrew starts taking photos of the clouds. “Manipur also has such beautiful clouds in winter mornings,” he says.

As they disembark at Aizawl and collect their four suitcases, the friends brace themselves for the rest of the journey. The comfortable and safe part is over. Now, they have to ride through the rugged terrain and an under-construction highway snaking the foothills of the Himalayas from Mizoram to Manipur.

The smells and sounds of the market outside Mizoram airport entice the two men to take a quick break. Women are selling fresh fruits and vegetables, and people have queued up at small eateries. After stuffing their heavy bags into an old Maruti 800, which will take them to the SUV, Andrew and Vaiphei decide they want to eat.

“I believe in travelling with a full stomach. Let’s have breakfast”, says Vaiphei. The choice of restaurants is confusing. It’s their first time in Mizoram and they want to make the most of it. They opt for traditional Mizo dishes, and choose Sanpiau and Sawhchiar, cooked with meat and rice, like porridge.

“It is quite similar to our food,” is their verdict. “We have similar roots like Mizoram, they are like our brothers,” says Vaiphei. “They saved us in this time of crisis.”

The Mizos and Kukis share deep ethnic ties–historically, culturally, and linguistically. The Mizo, Chin, and Kuki-Zomi tribes are known as the Zo people. Since May 2023, Mizoram has been sheltering over 12,500 displaced people, while providing relief and medical supplies to Kuki communities in Manipur. Early this week, Mizoram’s newly elected Chief Minister Lalduhoma said he expects President’s rule to be imposed in Manipur. Calling for a solution, he added that the “buck stops at the Home Ministry”.

But Vaiphei and Andrew don’t have the luxury to explore these shared connections.

“Sumo is waiting for you guys, hurry up!” shouts the driver of the Maruti 800 that will take them deeper into Aizawl city where they will catch the next ride to Churachandpur. The crisis has opened a new business—SUV services from Aizawl to Churachandpur and back. A single seat on a Bolero costs Rs 3,500. Vaiphei and Andrew are travelling in a 10-seater Sumo for a little over Rs 2,000 each.

After an hour or so, the car pulls up outside a shabby-looking shop. The driver points to a battered blue Sumo. “This will take you to Churachandpur.”

The suitcases are shifted from the trunk of the Maruti to the roof of the Sumo—blue, purple, and black bags stacked over each other next to white-packed jumbo-sized parcels that have dry food and medical supplies for the Kuki tribes in Churachandpur.

The men’s luggage is the last to be loaded. “Hey, hand me over those bags,” the driver of the Sumo, Anthony, yells. Vaiphei rushes towards the car catching a packet of tamarind chutney that he bought from a local “aunty” in one hand.

It’s indigenous to the tribals, he says, while passing his bags to the driver. The chutney of mashed tamarind and green chillies smacks in the face. “Woohoo, it is so good,” says Vaiphei.

Anthony is more concerned about securing the bags and packages. “It’s a bumpy, dusty, ride,” he says, testing the ropes binding them together before carefully covering them in blue tarpaulin. It takes him three hours to secure the luggage. “We can leave now,” he finally announces at 3 pm.

Anthony, a Kuki from Churachandpur, has been using this route even before NH 102B was built. A bumpy road is better than one with “no roads”, says Anthony, who makes the trip back and forth five to six times a month. “I am married to a Mizo woman. I travel on this road with my wife and son whenever she wants to visit her mother.”

Anthony’s wife Mary and their one-year-old son are travelling with him today.

“Are we ready,” Anthony asks.

Everyone shouts together “Yes”.

After half an hour on the road, Anthony suddenly stops the car. “We will pray here,” he says. It’s a short prayer—succinct and to the point. “Keep us safe,” Anthony murmurs before restarting the car.

Google Maps shows that it will take them 11 hours to cover the 331.9 kilometres to Churachandpur. But Anthony estimates it will be 20 hours. The road is rugged.

“Woah woah,” all passengers scream, as the car jumps over a series of bumps. “Sorry,” Anthony says.

On the bumpy road

The pock-marked road gives way to craters as they move deeper into the hills. Andrew and Vaiphei try to get some sleep, but the cold and the road jolt them awake every few minutes.

To compensate for the route, Anthony asks his wife to play some music from her phone. They listen to some old folk songs, but the Manipuri students don’t hum along. They’ve never heard these songs before.

“Have you heard, ‘Jab koi baat bigad jaye’?” asks Anthony, referring to the golden oldie from the 1990 movie Jurm. The students shrug. Understanding the mood, Anthony asks his wife to “play some Shah Rukh Khan songs”. Everyone is familiar with Bollywood songs and movies such as Hrithik Roshan’s Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai (2000) to Shah Rukh’s Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998).

Divided by ethnicity, united by Bollywood. And when Koi Mil Gaya songs start playing, they all join in, “Koi Mil Gaya, Koi Mil Gaya”.

When they stop for dinner, the students and Anthony’s family settle down for some Mizo food—chicken fry, pork curry, soup, mustard leaves curry, dal and rice.

“It is indigenous, devour it,” says Vaiphei.

Just then, his phone rings, stopping all conversation. It’s his parents checking on him.

“Mother, it is just the beginning of the journey, only one-fourth is done,” says Vaiphei. As they enter the more volatile areas of the Northeast, the calls become more frequent, more anxious.

When they resume the journey, Anthony comments on the “car spilling oil”. Before leaving Aizawl, Anthony had filled the tank at the last petrol pump. “I overloaded the diesel tank, now the car is puking the extra.”

Ghosts and a blurry future

By nightfall, fatigue sets in slowly during the next leg of the journey. There is no music, no internet, no network in these forested areas. The road gives way to muddy stretches, and the SUV starts to bounce earnestly. Vaiphei groans.

NH 102B is not like the four-lane highways of Northern India. It passes through dense forests in Mizoram and Manipur on routes used by traders for years. Before the violence started, it was the preferred route for illegal trade, but now it is the only lifeline for the Kuki-Zomi tribes travelling to the rest of the country. Families in Churachandpur depend on this highway for medical aid and food—though consignments rarely arrive on time due to landslides and heavy rains.

As she plays with her son, Mary talks softly to Anthony, perhaps to keep him alert as the road twists and bends in the dark.

“I am finding it difficult to sleep, the jerks keep waking me up,” says Andrew. They talk about ghosts and spirits, the existence of humans, God, and Christianity.

At the crack of dawn, the Sumo crossed the Mizoram border into Manipur. All six passengers are drowsy and irritable due to the lack of sleep, including the usually cheerful Vaiphei. “When will we reach?” he asks plaintively. Another three to four hours, Anthony replies.

The hills of Manipur were sparsely populated and had fewer forests. Anthony stops the car for tea at Singngat. “This place is infamous for bad roads, but this time we are witnessing it,” he said, sipping warm milk tea on the cold morning.

Close to their final stop, the young men discuss their future.

Andrew says he always wanted to become a doctor, but Vaiphei isn’t so sure anymore—not after everything he has experienced.

“If I would have studied something else, I would have been of some help to my community today,” says Vaiphei, as the SUV pulls up in front of the boys’ hostel. Now, he wishes he was someone important, “someone in a position of power to help, save and protect my community.”

Haha.. so these are the stories of those over inflated, exaggerated so call doc…

These kind of bumpy road is not new to any Manipuri.. so don’t be hyperbolic..

Nor we give a damn about their unnecessary struggle..

We also remember how the meetei doc and nurses serving in Churachandpur hospital were treated on 3rd May. And there are many untold story about them.

But unlike these two we don’t flash or broadcast like a hero… everyones struggling here… so stop your goddamn victim card play

These two got the prize of what their community asked for.

Neither meetei nor state govt are responsible for this issue.. before 3rd may all were in peace. Their community should have decided about things like this before committing their foolish act of vandalism.

Also in the medical field how can one pursue online course..?

We don’t care whether they study in Imphal or anywhere… people are dying daily in Imphal and hills and they are worried about thier career.??

Wahhhh

Please don’t publish such rubbish story. I don’t want my feeds to be flooded with such trash.

~A proud meetei Engineer.

Wrong article if u dont know the wholes story then dont write a fucking article….first clash breakdown is in Churchandpur they kill meetei innocent villager and burn down their home

ThePrint is always one-sided. I have never seen any article from them about the Meitei’s sufferings from Kuki Zo. Seems like they are benefitted from the poppy and other illegal earnings from Kuki Zo militants. I would recommend them to do little bit of research before they write or release any videos.

Karma – Good or bad, what you put out comes back to you.

The writer seems to completely ignore the fact that Meiteis can’t take the NH-39 that goes through Kuki dominated areas and hence have to take air route only if someone has to go to Guwahati.Besides many other misleading information saying everyone called them illegal immigrants is also not true as Meiteis have never said all of them are refugees. They have rose against Meiteis since Meiteis have been telling to not harbour other Burmese illegal immigrants and allow them to cut reserved forest for poppy cultivation.The article reflects the writer’s intention to garner sympathy for Kukis while totally ignoring the root cause of the conflict and attempt to divert the real issues.

Wht about imphal if u want to go imphal to nagaland u have to go through flight it cost 7k above the road is block by kuki narco terrorist refugee they take taxes any vehicle at national highway since long time if u don’t know anything about manipur don’t publish next time we know this page got money from kuki narco terrorist

Shouldn’t have started the violence if they don’t want such inconveniences. Meiteis are also struggling some had given up their education, job, dreams just because they couldn’t afford flight tickets, roadways were cheaper but kukis would brutally kill whoever passes their inhabiting areas.