New Delhi: “Look look,” shouts Brahmanand, an Odisha native who is a first-time visitor to Delhi’s deer park. He coos, makes kissing sounds, snaps his fingers —anything to capture the attention of the spotted deer that loiters ahead of him. The male, distinguished by its antlers, is unfazed. A couple of minutes pass, and it deigns to give in to his voyeur’s pleas. It turns around and stares serenely into the camera. Satisfied, Brahmanand leaves.

This is a common sight at Delhi’s Aditya Nath Jha Deer Park, one of the city’s flagship green spaces; an oasis for joggers and lovers alike amid the hubbub of Hauz Khas Village. A city institution for over half a decade, the park has undergone a massive shift in scale — from six deer in 1968 to a disputed 565 in 2023.

Not for long, though. The deer are moving out. 43 deer were sent to Rajasthan’s Ramgarh Vishdhari in August of this year, after an order passed by the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) in June.

The translocation of the deer is cloaked in confusion—they are everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The security guard seated outside the park says some have been moved. Deputy forest conservator of South Delhi, Mandeep Mittal, says the project is yet to begin. The security guard outside Asola Bhatti Sanctuary, one of the herd’s new homes, says there are a few inside. . A forest department official told The Indian Express that the animals can only be moved post-breeding season, which is ongoing.

An order passed by the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) in June sanctions a change in the deer park’s identity by putting to a stop its recognition as a ‘mini zoo’. This involves the translocation of deer in a 70:30 ratio to two wildlife reserves in Rajasthan — Mukundara Hills National Park and Ramgarh Vishdhari — and Delhi’s Asola Bhatti Sanctuary. The park will remain under the jurisdiction of the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), but its immediate future is in flux.

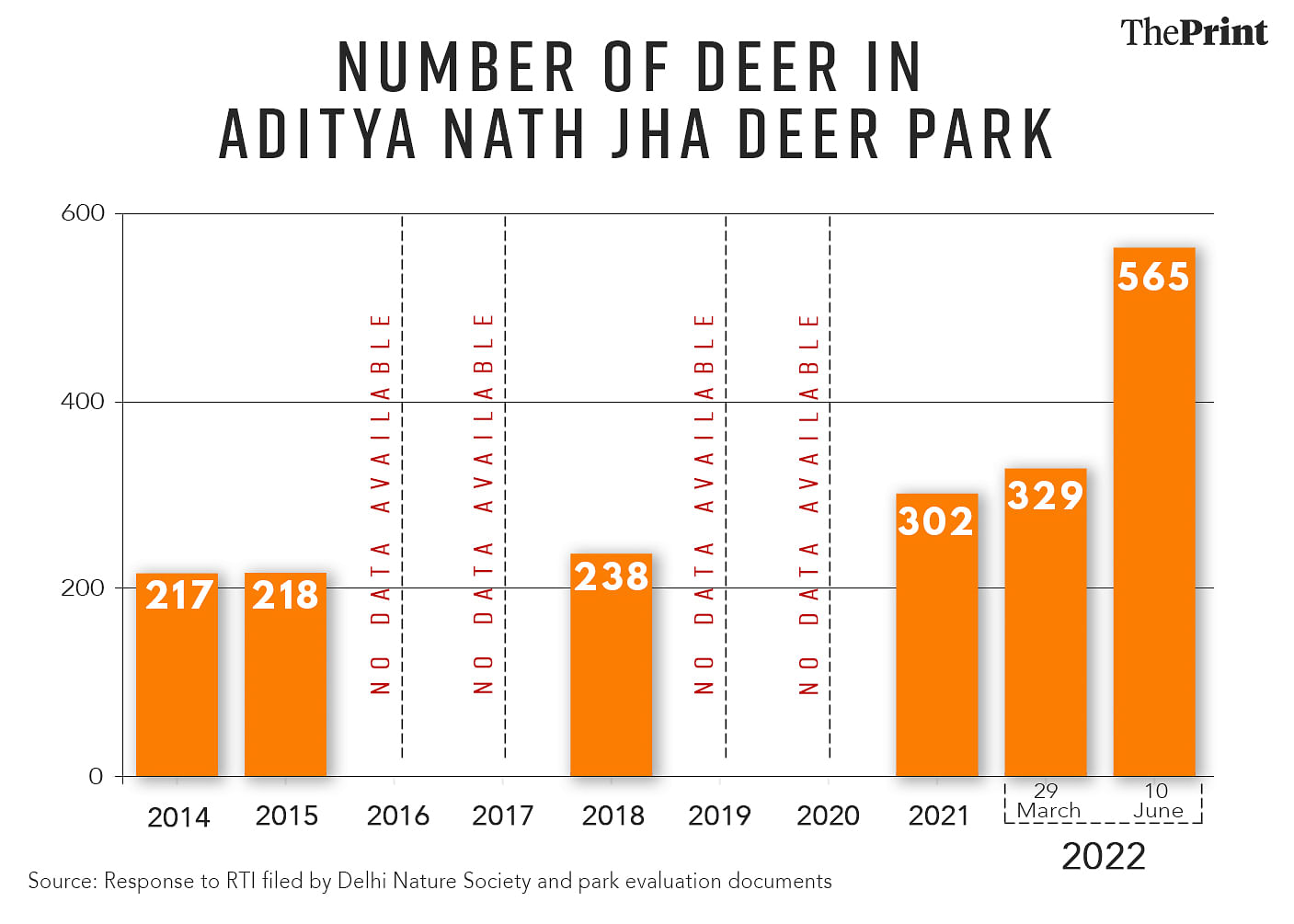

Activists and animal lovers are far from thrilled. The authorities cite overcrowding as the reason behind the move, but calculations don’t add up. According to data accessed by ThePrint, on 31 March of last year, DDA said there were 329 deer. Three months later, on 10 June, this number had increased by over 200 — to 565.

Before releasing the June numbers, in May, the DDA said they had made “a mistake” while counting. A letter was sent to the Chief Wildlife Warden of Rajasthan, wherein the principal commissioner of the horticulture department, Delhi said they “were finding it difficult to manage the larger number of deer.” The month after, researchers from Amity University were deputed for counting, after which the claim of 565 was made.

But the question stands: how did the number go up by this astonishing sum?

“If you’re closing down the park, even one deer would seem like one too many,” said Ravi Chellam, wildlife conservationist, CEO, Metastring Foundation, and coordinator, Biodiversity Collective.

Protests have been held at the park by citizens and environmental groups. “Be dear to our deer,” read one placard. Verhaen Khanna, founder of the New Delhi Nature Society, a local environment advocacy group, has filed a petition in the high court, alleging mismanagement and the flouting of CZA guidelines by the DDA. “The deer have suddenly appeared out of thin air. We’ve taken out RTIs and seen the evaluation documents. There are multiple discrepancies,” he said. The response to the RTI has been accessed by ThePrint.

https://x.com/DelhiTreesSOS/status/1684749626719784960?s=20

“It has taken 55 years for the number to reach 329. And now in 2 months…,” Khanna said, questioning the jump.

In 2014, there were 217 spotted deer (also known as chital) at the Deer Park. In 2015, there was a reported increase of 1, placing the number at 218. For the next two years, no numbers are available. In 2018, there were 238. The next population count was in 2021, according to which there were 302 deer.

Activists call it a conspiracy. They say the agenda is to revamp the park, to

commercialise it and turn it into an “eco-tourism hub.” And the deer have been caught in the crossfire. In its current avatar, the park is mundane, with far superior alternatives. The deer is its solitary claim to fame.

A European family of three ambles through the 64-acre space, of which 10 have been cordoned off for the deer. They pause at the animal enclosure. Not much is visible, the deer have been provided with two layers of protection. The first is a chain-link fence, a covering made of steel wire. The second is a layer of green mesh. Both were introduced for the protection of the deer. “My friends told me there were deer here. It’s obviously not Delhi’s main tourist attraction, but we knew about them,” says the son.

Also read: Arikomban is a wayward son of Kerala and a mini-celebrity. But where does he really belong?

Leopard fodder

According to the CZA, one purpose behind the transfer is the need to supplement the prey base for the seemingly thriving population of leopards at Asola Bhati, the city’s Tughlakabad-based urban jungle that seeps into the outskirts of the city. “The CWLW, NCT of Delhi stated that as per latest census, the number of Leopards (Panther pardus fusca) in Asola-Bhati Wildlife Sanctuary, Delhi has risen to 18 and there is need to supplement the prey base,” reads the order by the CZA.

But Mandeep Mittal, Deputy Wildlife Conservator, South Delhi, said no such census has been conducted. “There is no hard evidence. Sightings have increased,” he told ThePrint. Based on this, it is assumed that the population has risen. The guards outside the sanctuary chime in: “10 to 12 must be there,” one says confidently. The other nods in agreement.

They [the DDA] want to feed them to the leopards. They want to kill them, they don’t want them to survive

– Verhaen Khanna, founder, New Delhi Nature Society

Counting the leopard of Asola is a purportedly tedious process, because the area extends into Rajasthan and Haryana and is part of leopard corridors. “Small studies have been conducted, but no proper intervention has been made. We are in the process of initiating the census,” said Mittal.

However, the idea of deer being taken away, only to be converted into leopard fodder, has tugged at the heartstrings of animal lovers. And fueled their anger. “They [the DDA] want to feed them to the leopards. They want to kill them, they don’t want them to survive,” said Khanna.

Mittal has a different take. “The intent was not to bring them as prey. There is a sufficient prey base [at Asola]. This is the wrong way of putting it. The most likely reason is that the area has a large population of deer,” he said.

In the context of wildlife management, the situation at Delhi’s deer park raises important questions about conservation practices. The challenges faced by the deer population highlight broader issues in wildlife protection, as discussed in the article India losing its status as a conservation leader, which examines the implications of urban development on natural habitats.

Even so, the very act of releasing captive animals into the wild is not one that conservationists necessarily agree with. “Levels of inbreeding are high and the health of the animals is likely to have been compromised. These deer will have diminished skills to survive in the wild due to their prolonged confinement and being fed by humans, and as a result, may find it difficult to navigate the wilderness in unfamiliar forests,” said Chellam.

Also read: Delhi has given up fixing monkey problem. Courts, committees, tenders—nothing’s working

No compliance by DDA

According to a notice sent to the DDA by the CZA in March of 2021, the park needed to meet certain parameters for the renewal of its recognition. This included placing a ban on the entry of food from outside. The DDA has far from complied with this instruction.

Throngs of people enter the park daily. There are those who come for their daily rounds of exercise, but crowds invariably form outside the deer enclosure. Novices peep through holes in the mesh, but seasoned visitors collect towards the end of the path—where the authorities appear to have run out of mesh.

In this corner, slices of bread are wielded like weapons and upper-arm strength is put to the test. The fence is of a reasonable height but fails to serve as an effective barrier against the determination of those who will go to any extent to feed the animals. Slices of bread are distributed among families and then flung into the enclosure. The deer hastily arrive, a motley crew of various ages.

A woman begins throwing puris past the boundary with surprising speed. One of them hits a deer, who turns around to look at her. It’s a simple formula: the quantity of food increases, and so does the number of deer. More people start to gather, intrigued by the clamour. Some participate in the zoo-specific sport of food-throwing, some click pictures, and a few stare—oddly transfixed.

Levels of inbreeding are high and the health of the animals is likely to have been compromised. These deer will have diminished skills to survive in the wild due to their prolonged confinement and being fed by humans…

-Ravi Chellam, Conservationist

The order also said that deer carcasses are being buried in the enclosure itself and that post-mortems should be conducted.

The CZA also told the authorities that “no measures” for keeping the population in check had been enforced, which needed to be done “immediately.” The CZA’s suggestion was that male and female animals should be segregated. This does not appear to have happened. The park’s 2022 evaluation document, accessed by ThePrint, also confirms that no sterilisation has taken place.

Also read: A leopard walked into Delhi’s Yamuna Park. Then an AAP minister illegally took it out

Has the move begun?

Delhi’s AN Jha Deer Park was opened to the public in 1968, when six deer were brought in. Over the last nearly fifty years, the population has been given room to grow and grow. The result of this wanton growth? Inbreeding.

Officials have cited inbreeding as one of the causes behind the declassification of the park as a mini zoo. But activists question the viability of this claim. However, “once released the animals are likely to disperse. This could prevent an increase in levels of inbreeding,” said Ravi Chellam. “But to completely solve the problem of inbreeding, unrelated males need to start breeding with the released females.”

Inbreeding leads to genetic abnormalities and offspring with lower chances of survival.

According to a security guard at deer park, the deer are fed once a day by a DDA official. This is then further supplemented by a feast provided by a legion of Delhiites. As a result, the foraging abilities and instincts of the animals have been compromised.

According to CZA guidelines, one of the prerequisites for releasing captive animals into the wild is the ability of the creature to adapt to its new setting “and fend for itself successfully.” The guidelines also call for a level of discrimination to be followed. Pregnant deer cannot be transported, neither can velvet-antlered deer.

Khanna, who is also the petitioner in the case against the DDA, remembers seeing a truck at the premises, into which deer were being ushered. According to him, food was used as bait, and they were lured in. Through blurry photographs, if one squints, the number plate on the truck can be made out — it is from Rajasthan.

However, blurred as they are, the pictures provide a modicum of clarity. “43 chitals have come to us so far,” said Sanju Sharma, officer-in-charge at Ramgarh Vishdhari. This is in addition to the approximately 600 chitals already there, some of which are “natural” and others results of translocation from wildlife reserves in and around Rajasthan.

The area was named a tiger reserve last year. It currently has a fledgling population. Two females, one male, and a lone juvenile. A total of 100 deer are due to come in, and Sharma expects them to come within the next month. “The mission is ongoing,” he said.

According to an NDTV report, last month, 23 deer were introduced into Ramgarh Vishdhari. The report doesn’t specify where they came from, but mentions a ‘Delhi zoo.’ It also says they were transported via a truck. Sharma confirmed that the deer were indeed products of the park.

The DDA, in response to the RTI, had stated that “protocols for translocation will be strictly adhered to and Boma technique will be used to ensure minimal disturbance to the animal.” With its origins in Africa, animals are moved through a “funnel-like fencing” that mirrors their external environment, in this technique. There are grass mats and green nets. Through the funnel, animals are herded into a larger transport vehicle, through which they are finally moved.

The argument is that there is no concrete evidence to suggest which transport technique was finally used. “We don’t know how they’ve translocated the animals. We’re inquiring into translocation,” said lawyer Arvind Sah, who is fighting the case on behalf of New Delhi Nature Society. Although, according to Sanju Sharma, the Boma method was used.

The contradictions, questions and suspicions are at the core of the skirmish. “It doesn’t look like the Boma method was used at all,” says a member of the New Delhi Nature Society, rolling her eyes. She is referring to the pictures.

At the centre of the furore, of course, are a bunch of spotted creatures. They loll about, undaunted by the commotion surrounding their departure. “They shouldn’t remove all, at least some should stay,” said Brahmanand, appalled at the thought that the subject of his photographs could soon become leopard fodder.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)